Rural Rockets and Rainbenders

In 1972, the pioneering architect and inventor Steve Baer created the “Zome Home,” a passive solar-powered house that allowed him to live completely off the grid. Wildly inventive, the angular, dome-shaped structure looks like something that might exist in the Star Wars universe. Dispersing his ideas through publications like Dome Cookbook, Baer garnered a small but devoted cult following of environmentally conscientious do-it-yourself amateur architects. Breathing fresh life into Baer’s ideas, California-based artist Oscar Tuazon represents the next generation of zero-waste domestic architecture. Water School, on view at Michigan State University’s Broad Art Museum, brings together a cross-section of Tuazon’s experimental works which collectively suggest practical possibilities for more environmentally sustainable living.

Tuazon’s work has appeared in a host of major venues in America and abroad, including Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art, the Whitney, the Centre Georges Pompidou, Art Basel, and the Venice Biennale. His interactive Water Schoolat the Broad complements two other similar “schools” Tuazon created in California and Minnesota (both locations that experienced moments of water crisis: drought in California, and the Dakoda Access Pipeline in Minnesota). The schools serve as spaces that cultivate discussion about sustainability.

Oscar Tuazon, Zome Alloy, Plywood, aluminum sheeting, and hardware, 171 x 826 1/4 x 768 7/8″ , 2016 – Courtesy the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich

The centerpiece of the exhibition is Tuazon’s Zome Alloy (2016), a full-scale plywood prototype of several rooms inspired by Baer’s signature polygonal “Zome Home” (a term coined by Baer’s friendSteve Durkee, referencing the dome shape of each module). Here, Tuazon erected three interconnected rooms taken from the complete structure which was originally displayed at Art Basel, 2016 (the other rooms are on view in his other Water Schools). Zome Alloy isn’t functional as an actual home, but serves as interactive sculpture/architecture. Its rooms contain a library of books selected by Tuazon from the MSU library because, as Tuazon says, “ever school begins with a library.” The subjects range from art and architecture to science and activism. For the duration of the exhibition, the space will host interactive sessions, variously termed read-ins, write-ins, and speak-ins. So while Zome Alloyis displayed as sculpture, it will also quite literally serve as an interdisciplinary school, creating space for conservation conversations to occur.

Oscar Tuazon, Rainbender (E 3rd) Velux skylight, aluminum, steel, borosilicate glass, vinyl, Sharpie, enamel, and water – 41 x 61 x 35″, 2018 – Image Courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York

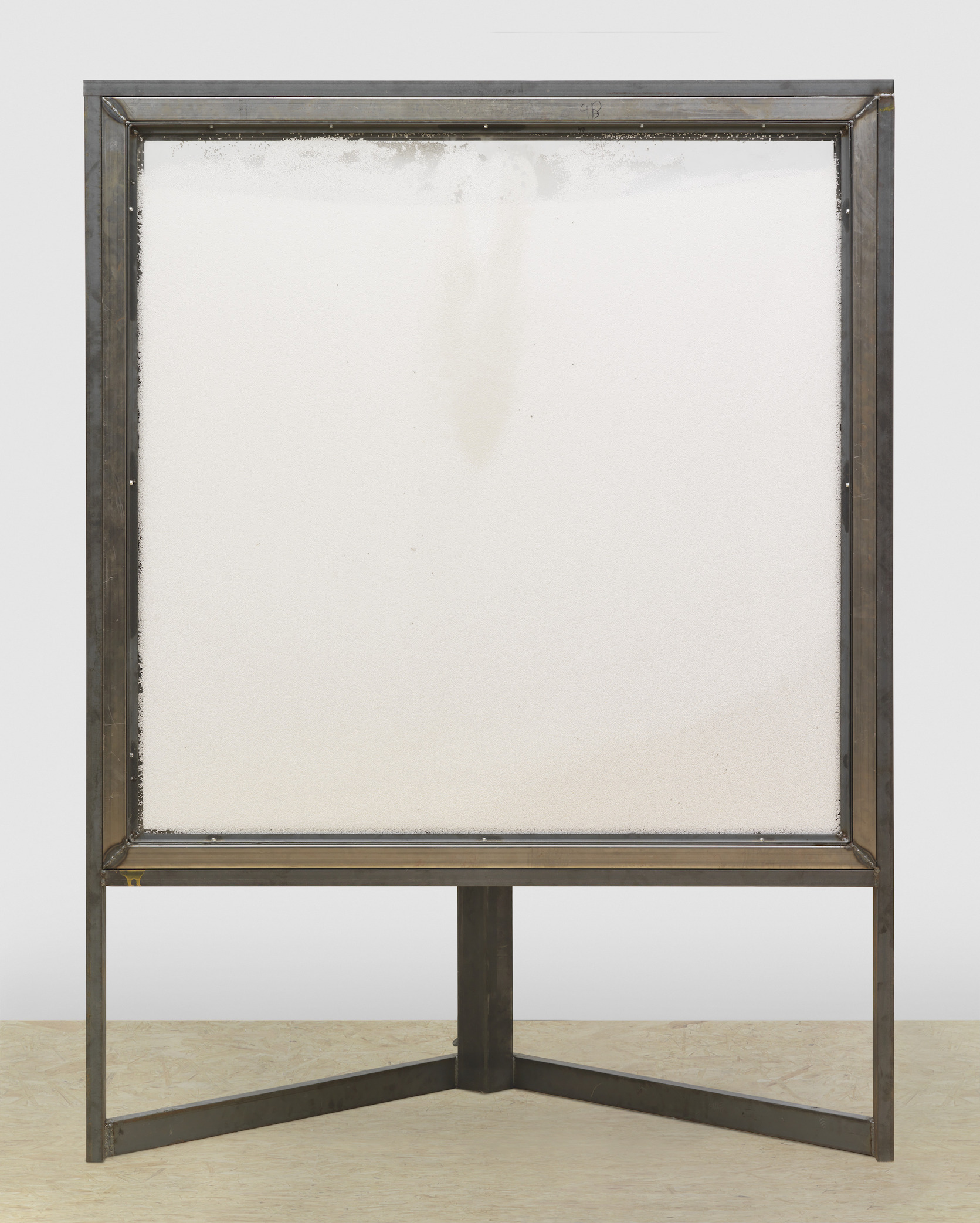

Unlike conventional solar-powered homes, Baer’s Zomes applied passive solar power, meaning that the architectural elements of the home harness solar energy without the aid of any electronics or waste-producing fuel. For example, the south face of Baer’s home (which faced the sun most of the time) contained large window bays which held dozens of large drums filled with water, serving to cool the house by day and insulate the house at night. Working in the same spirit, Tuazon created experimental prototypes for architectural elements that serve as examples of how we might live more efficiently. His Rocket-Stoveis a highly efficient heating system that produces almost no smoke, and his Rainbendersare designed to capture water in regions that receive less than 15 inches of water per year. Perhaps the most inventive architectural element is his Curtain Wall, a window comprised of two large panes of glass set within a frame (imagine a glass shadowbox); during the day, it functions as a window and lets in sunlight, but at night the space between the panes can be filled with polystyrene beads, which serve as highly effective insulation.

Oscar Tuazon, Curtain Wall, Steel, acrylic, electrical components, steel drum, loose polysterene beads, and tinted Plexiglas – 91 3/8 x 67 7/8 x 46 7/8″, 2013, Courtesy The Brant Foundation, Greenwich, Connecticut

A final room in the exhibition displays selected ephemera and publications produced by the first-generation environmentalists (Steve Baer, Buckminster Fuller, and Stewart Brand) which inspired Tuazon’s own work. These writings include Baer’s Dome Cookbook (1969), which disseminated Baer’s ideas and encouraged a movement of do-it-yourself sustainable architecture.

The works on view in Water School might admittedly be disappointing if approached purely as aesthetic objects, though the unabashed zaniness of the Zome is undeniably visually satisfying. But more importantly, Tuazon’s practical experimentation makes the point that zero-waste living is a real possibility. Furthermore, his work carries an enduring relevance. After all, in Michigan we have over 3,000 miles of freshwater coastline (more than any other state except Alaska), but issues like the Kalamazoo Oil Spill and the Flint water crisis demonstrate that water, though necessary to sustain life, is hardly something we can take for granted.

Oscar Tuazo, Water School will be at the MSU Broad Museum through August 26, 2019.