Imperial winter dragon robe, China, early 19th century, embroidered silk. University of Michigan Museum of Art, Gift of Elizabeth Henshaw Gasper Brown in memory of Horace, William and Helen Lou, 1989/1.34

In Western visual culture, copying is sometimes freighted with duplicitous or subversive undertones. Marcel Duchamp’s notorious LHOOQ, a defaced poster of the Mona Lisa, is hardly flattering to the original, after all. But drawing mostly from the University of Michigan Museum of Art’s permanent collection, the exhibition Copies and Invention in East Asia showcases the many ways the artists of China, Korea, and Japan actively copied and referenced pre-existing visual motifs across borders and across time.

There are over a hundred works on view which snugly fill the UMMA’s spacious Taubman Gallery, mostly gleaned from the past (the oldest artifacts coming from Han Dynasty China, about two millennia ago), though there are a smattering of 20th century and contemporary works on view. The chronological and geographical scope of this exhibit is ambitiously large, so the show is compartmentalized thematically; there’s a section on literati painting, for example, and another on the auspicious animal symbols that recur.

Seifû Yohei III, White teapot and sencha pitcher with stamped dragonfly designs, circa 1893-1914, porcelain with clear glaze. University of Michigan Museum of Art, Bequest of Margaret Watson Parker, 1954/1.512 and 503

A set of ceramic bowls by the celebrated artist Seifu Yohi III are a case-study for how Japanese art imitated and synthesized the visual cultures of the territories conquered by imperial Japan. Yohi intently studied pottery from China’s Ming and Song Dynasties (of which there are some examples on view), and his artistic output is one of respectful mimicry. Employed by the imperial household, his work, characterized by its fine, milky-white glaze, reflected the interest Japanese patrons had in Chinese art.

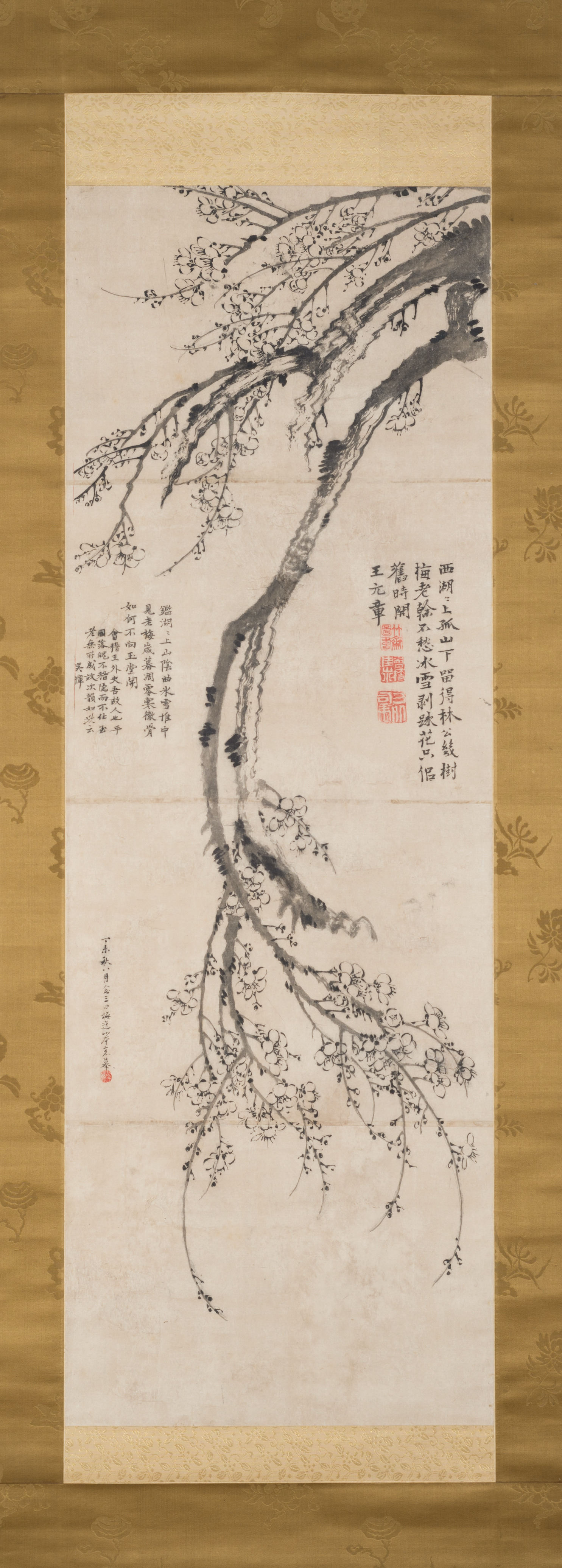

Yamamoto Baiitsu, Blossoming Prunus Branch, after Wang Mien, 1847, hanging scroll, ink on paper. University of Michigan Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. C.D. Carter, 1970/2.156

Copying at its most literal is demonstrated by the Japanese landscape painters who replicated their original Chinese models, right down to the signatures of the original artists, though their intentions were never deceptive. An elegant ink painting of a wispy tree branch by 19th century Japanese artist Yamamoto Baiitsu is an example, its architype being a 14th century work by Chinese artist Wang Mian. And an impressively large hanging scroll demonstrates how even within China itself, artists would directly copy preexisting Chinese paintings. Wu Wei’s Travelers on a Mountain Pass (painted, incidentally, at exactly the same time Leonardo was dabbing away on the Mona Lisa) is a tribute to a painting by the 10th century artist Li Cheng, though Wu’s painting is more abstract, retaining a definitive personal style. This is also a painting that advances the case for seeing art in person; cinematic in scale, this work practically engulfs the viewer, an effect that would get lost in translation if reproduced in a book.

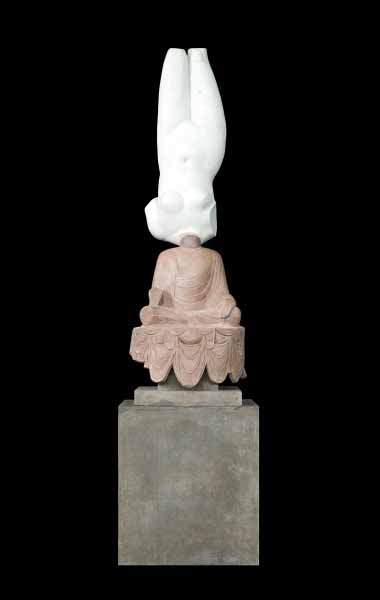

XU ZHEN ® Eternity-Aphrodite of Knidos, Tang Dynasty Sitting Buddha, 2014, glass fiber-reinforced concrete, marble grains, sandstone grains, mineral pigments, steel. Courtesy of James Cohan Gallery, New York ©Xu Zhen

For me, the most visually compelling works are the several contemporary sculptures on view. South Korean artist Chul Hyun Ahn’s deceptively simple light sculpture Two Circles, placed right at the show’s entrance for maximum impact, comprises two colored circular florescent lights positioned concentrically between two mirrors, framed and mounted on the wall; stand directly in front of Two Circles, and the illusion is that you’re staring into an infinity of circles eternally receding into the distance. Chul Hyun Ahn’s sculptures are abstract references to Zen Buddhist ink paintings, characterized by a reductive though elegant simplicity. Approaching copying with a wry sense of humor, sculptor Zu Zhen created a literal mash-up of two iconic images in Eastern and Western visual culture: a seated Tang Dynasty statue of Buddha seems to sprout (where its head should be) an upside-down reproduction of the Aphrodite of Knossos.

Copies and Invention in East Asia, to its immense credit, takes a comparatively niche topic and makes it interesting, accessible, and visually punchy. It’s a diverse show, ranging in scope from 2000+ year old Chinese burial objects to a set of countertop Buddhist stupas fresh off the 3D printer. It’s a show that playfully gives tangible expression to the Japanese literary critic Hideo Kobayashi’s assertion that “Copying is the mother of creation.”

Textures of Detroit @ Kreft Center Gallery

Installation , Textures of Detroit, Kreft Gallery, 2019

Textures of Detroit is an exhibition of work that revolves around the theme of visual and tactile textures of Detroit. It’s an intimate, multimedia show of six seasoned and accomplished contemporary Detroit artists (Peter Bernal, Matt Corbin, Roy Feldman, Carol Harris, Carl Wilson, and Ann Smith), whose sometimes rugged and gritty work is almost a foil to the chic polish of Concordia University’s Kreft Center Gallery.

The exhibition opens with a fine salvo of woodblock prints and linocuts by Kresge fellow Carl Wilson, who last year enjoyed a show at the Grand Rapids Art Museum. It’s not hard at all to imagine these as still frames from noir film; they seem like storyboarded images or concept art for black-and-white cinema, evocative of soulful and morose saxophone riffs. In one graphic-novel style image, we see a line of beleaguered workers trundling toward the beginning of their shifts at some industrial job. In another an elderly woman sits alone in a dark room illuminated by a solitary hanging bulb, and nurses a glass of indeterminate substance.

There are several textile works on view by textile artist Carole Harris, who creates fiber art that seems almost painterly, and, at times, even sculptural. Her color palate is rusty and industrial; it’s no surprise to learn she draws inspiration from aging architectural structures. Move in close, and her arrangements of patchwork abstractions reveal a dizzying network of swirling stitch-work that recalls the pirouetting clouds of Van Gogh’s Starry Night. Her works subtly reference the time-worn textures of urban Detroit, and they exude an undeniable beauty.

Roy Feldman, “Untitled,” Silver Halide print on Kodak Endura paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

A quintet of photographs by Roy Feldman, a Detroit-based photographer and Emmy-Award winning filmmaker, presents a set of images of multi-layered urban interiors, each characterized by disorienting reflections which lend the set an air of magic-realism, an effect the photographer here achieves by capturing images of people taken ether reflected in mirrors or viewed through windows, a device which misleadingly lends the images the initial appearance of being double-exposed. In one instance, we see the side of a cropped face of a woman applying eyeliner; she holds out a small, circular mirror which reflects her eye as it seems to gaze back directly at us, though seemingly disembodied like a hovering object from a painting by Rene Magritte.

Roy Feldman, “Untitled,” Silver Halide print on Kodak Endura paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

Ann Smith and Mark Corbin both create sculptures from found objects and detritus, though their respective styles are certainly distinct, Corbin’s works rhyming more with the unrefined assemblage-style works of Detroit’s Tyre Guyton (of the Heidelberg Project), and Ann Smith’s works clearly more fussily worked and refined; the curvaceous metallic wisps of her Squash Blossom are a sort of cursive in 3D. Together, along with the fiber works of Carole Harris, this ensemble presents Detroit texture in the most literal sense.

Carol Harris, In the Spirit, 69 x 71″ textile, 1992

Like the Copies and Invention show on view at the UMMA, Textures of Detroit takes a relatively niche point of departure and delivers an immensely satisfying result. It’s eclectic, for sure, but these multimedia works seem to come together not just through their application of tactile and visual texture, but also through the understated affection they seem to exhibit for the Motor City, its textures, and its people.