Conscious Response: Photographers Changing the Way We See, an exhibition on view at the Detroit Institute of Arts

An installation view of Conscious Response: Photographers Changing the Way We See, on view at the Detroit Institute of Arts through Jan. 8, 2023

A photo exhibition of gifts and new acquisitions at the Detroit Institute of Arts, Conscious Response: Photographers Changing the Way We See, highlights impressive new talent from the Detroit area, as well as big names from the photographic canon whose work, mostly in black-and-white, you’re likely to recognize. The show is up through Jan. 8.

Nancy Barr, the James Pearson Duffy Curator of Photography, has selected work by 17 international artists to illustrate the depth and breadth of the collection, which was first assembled in the 1950s right as photography began entering major museums as a bonafide art form.

Conscious Response is staged in the Albert and Peggy de Salle Gallery of Photography on the museum’s first floor, not far from Kresge Court — a highly comfortable space with the Goldilocks virtues of being neither too big nor too small. You’ll want to browse at leisure.

Among recent famous gifts are works by the legendary Bruce Davidson, including some of his “street gang” series, as well as the iconic image from the 1965 march from Selma to Birmingham, Ala., of a young man with “VOTE” stenciled in white on his forehead.

There are also new prints by the celebrated Diane Arbus, who hasn’t been on display at the DIA in some time. One recently acquired image numbers among her most famous – Child with Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park, NYC, 1962 – and for good reason. The backlighting behind the little boy may be gorgeous, but it’s the child’s thrillingly unhinged expression – Talk about the decisive moment! — that propels this from documentation to artwork, momentarily freezing the viewer in place (who, like as not, is stifling a giggle).

In addition to heavyweights from decades past, Barr pulls in a number of young, emerging voices from metro Detroit, as well as outsiders like Farah Al Qasimi who’ve done extensive work locally.

Farah Al Qasimi, Shisha, 2019; Pigment print. Museum Purchase, Albert and Peggy DeSalle Charitable Trust and Asian Art Deaccession Fund, 2021.289. © Farah Al Qasimi, 2022.

Originally from the United Arab Emirates, the 31-year-old New Yorker with a Yale MFA spent a month in Dearborn three years ago shooting everyday life in the Arab-American community on a residency supported by Wayne State University, the Arab-American National Museum and the Knight Foundation.

“I fell in love with Dearborn really fast,” Al Qasimi told the South End, the Wayne State student paper. “It felt like home – more like home than my home.” That affection shows. Shisha, a shot of a romantic couple in a green-lit hookah lounge, their faces hidden behind a greenish cloud of tobacco smoke, is both kind of a hoot and a gorgeous color study.

Exploring notions of home and identity as well is local photographer Jarod Lew who, according to Barr, is just about to start his own graduate photography program at Yale. The young man’s artistic journey is intriguing. In 2012, Lew discovered his mother had been engaged to Vincent Chin when the Chinese-American man was beaten to death in 1982 in Highland Park – on the very night of his bachelor party — by two auto workers enraged by Japanese inroads into the U.S. car market. (The pair, by the way, never served jail time.) That unsettling discovery set Lew on a path to shoot family and friends in their homes as a way of documenting and giving face to Asian-Americans in the Motor City.

Like so many first-generation kids, Lew’s had to straddle the pull of competing identities. He’s famously said that when he’s at his mother’s home, he’s the least-Asian thing in sight, but once outside, he’s the most. It’s a disorienting phenomenon he illustrates with The Most American Thing, a self-portrait in which Lew lies on a sofa in a room crammed with Asian artifacts, his yellow hoodie pulled so tightly around his head that only his eyes and nose are visible.

Jarod Lew, The Most American Thing, 2021. Pigment print. Museum Purchase, Albert and Peggy DeSalle Charitable Trust and Asian Art Deaccession Fund, T2022.73 © Jarod Lew, 2022.

Illustrating that identity tug-of-war as well is Gracie, in which a skinny, young Asian woman stretches her hands over her head in an awkward pose while surrounded by a profoundly “American” dining room, complete with fussy china cabinet and large painting of a woman on the wall who’s undeniably white.

There are a lot of things that make this picture great, including Gracie’s Bart Simpson t-shirt, where America’s favorite buffoon is speaking Korean. Then there’s the peculiar white, paper mask stretched across the young woman’s face. Did the photographer interrupt her midway through a beauty treatment, or, a bit like the room décor, is this a high-concept reference to racial identity? Ghostly Gracie isn’t saying.

Several photographers wrestle with crises that have plagued the recent past, including Merik Goma, a Manistee native now living in Connecticut whose Your Absence Is My Monument conjures up a spellbinding sense of loss tied to the covid pandemic.

Merik Goma, Your Absence Is My Monument, 2020; Pigment print. Museum Purchase, Mary Martin Semmes Fund, T2022.23, © Merik Goma, 2022.

Goma, who’s partway through an 18-month, $150,000 artistic fellowship with the Amistad Center for Art & Culture in West Hartford, creates painterly tableaux in his studio that serve as affecting backdrops for his portraits. In Your Absence, a sober young African-American woman sits in front of a window with an empty birdcage, door wide open, next to her. The lighting is gorgeous, even if the overall vibe is somewhat funereal.

Equally funereal in its own way is LaToya Ruby Frazier’s The Flint Water Treatment Plant, an aerial shot of the huge water tower that’s become the visual symbol for the lead-pipe calamity in Buick’s one-time hometown.

A photography professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Frazier first traveled to Flint in 2016 on a magazine assignment, but subsequently got to know the local Cobb family, and spent five years documenting both their struggles and the city’s. Her work there has just been published in a new book, LaToya Ruby Frazier: Flint Is Family in Three Acts.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Flint Water Treatment Plant, Flint, Michigan, from Flint Is Family, 2016; Gelatin silver print. Museum Purchase, Albert and Peggy DeSalle Charitable Trust and Asian Art Deaccession Fund, 2021.247. © LaToya Ruby Frasier, 2022.

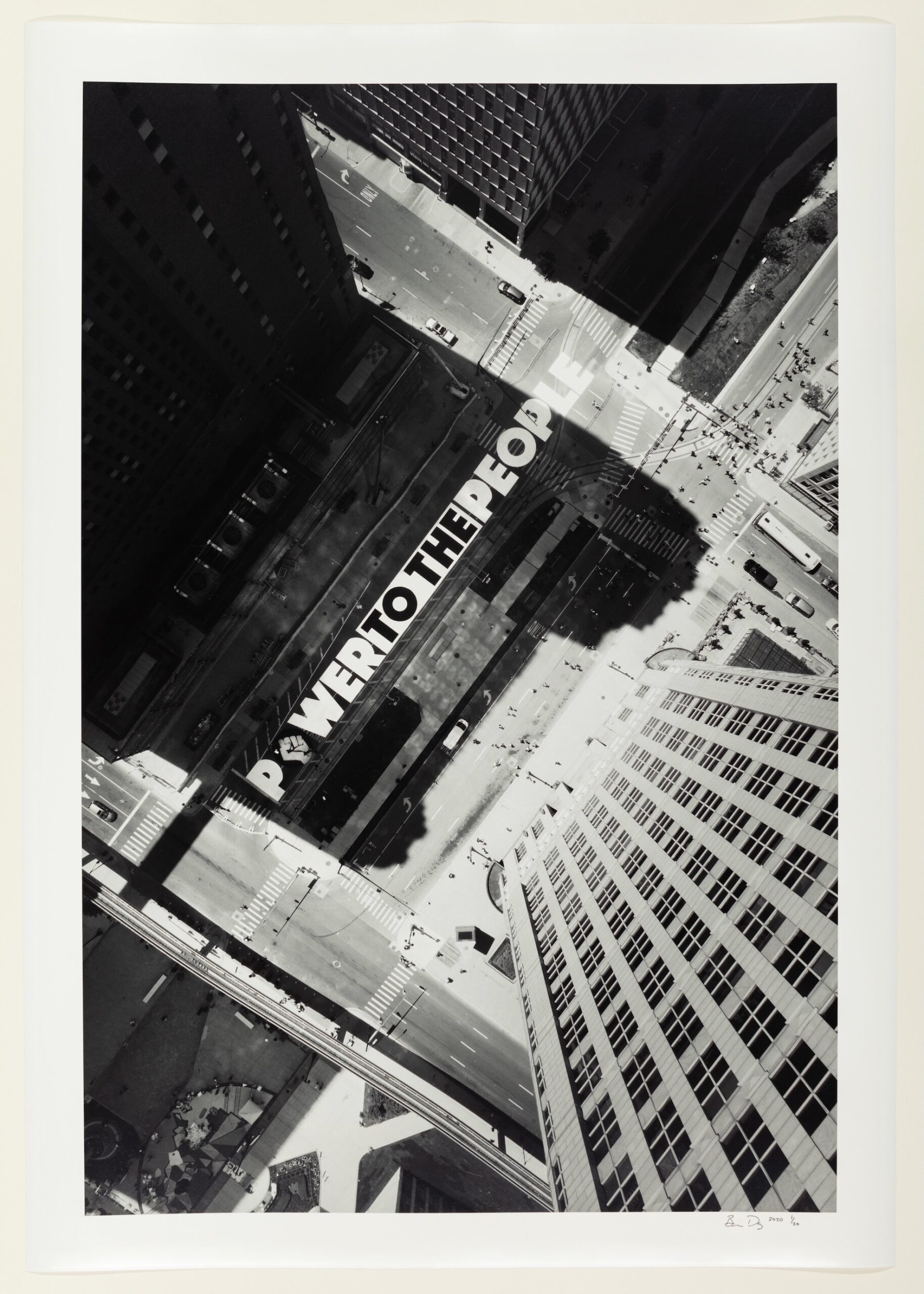

Finally, a Detroiter who’s turned drone photography into a mesmerizing art form, Brian Day, gives us a straight-down picture of the 2020 mural that artist Hubert Massey painted with high-schoolers on Woodward Avenue between Congress and Larned. The work honors Juneteenth, now a federal holiday, that celebrates the date when the last African-Americans in Texas finally learned they were free citizens, June 19, 1865.

Day’s dazzling drone work was compiled last year in Detroit from Above, which is available from Peanut Press Books. Happily, the artist hasn’t limited himself to just aerial photography, however gripping that may be. Conscious Response also includes some of his Planet Detroit series, a project launched in 2010 that stars the city’s denizens.

Brian Day, Woodward Avenue, Hubert Massey Mural, from Detroit from Above, 2020; Pigment print. Museum Purchase, Coville Photographic Fund, 2021.37. © Brian Day, 2022.

Conscious Response: Photographers Changing the Way We See, on view at the Detroit Institute of Arts through Jan. 8, 2023.