Aerial Image of the Venice, courtesy of the Venice Biennale

I attended the Venice Biennale for the first time in 2015 and visited the Arsenale location, which was an all-day event, so this time I attended the Giardini location and other venues throughout the city.

The Venice Biennale was created by a resolution of the City Council in April 1893, which proposed the founding of a “biennial national artistic exhibition” to take place in the following year to celebrate the silver anniversary of King Umberto and Margherita of Savoy. The event, in fact, took place two years later, opening on April 30, 1895, and is known most commonly within the art world as the oldest large-scale international contemporary art exhibition.

Although there are two major sites for viewing art, there are many satellite venues throughout the city. This year’s curator, Christine Macel, has called it an exhibition inspired by humanism. She says, “This type of humanism is neither focused on an artistic ideal to follow nor is it characterized by the celebration of mankind as beings who can dominate their surroundings. If anything, this humanism, through art, celebrates mankind’s ability to avoid being dominated by the powers governing world affairs.”

The Viva Arte Viva 57th Venice Biennale offers a route that unfolds over the course of nine chapters of artists, beginning with two introductory realms in the Central Pavilion in the Giardini, followed by seven more realms to be found in the Arsenale and the Giardino delle Vergini. There are 120 invited artists from 51 countries around the world; 103 of these are participating for the first time.

Lorenzo Quinn, City Sculpture, Courtesy of the Detroit Art Review, 2017

Early in May 2017, contemporary artist, Lorenzo Quinn, unveiled his new monumental sculpture at the Ca’ Sagredo Hotel, Venice. The installation, part of the Biennale, showcases Quinn’s artistic progression and his experimentation with new mediums and subject matter to transmit his passion for eternal values and authentic emotions. This sculpture was located right next to my Vaporetto stop at Ca D’ Oro.

Quinn addresses the human ability to change and re-balance the world around us – environmentally, economically, and socially. The sculpture has both a noble air as well as an alarming one – the gesture being both gallant in appearing to hold up the building while also creating a sense of fear in highlighting the fragility of the building surrounded by water. “I wanted to sculpt what is considered the hardest and most technically challenging part of the human body. The hand holds so much power – the power to love, to hate, to create, to destroy.” says Lorenzo Quinn.

Sam Gilliam, Drapes, Courtesy of the Venice Biennale 2017

With so much work at the Venice Biennale, it’s probably easier to focus on American artists, a Russian artist and one artist in particular from Detroit.

Sam Gilliam, whose work has been exhibited at the N’Namdi Contemporary Center in Detroit, was born in 1933 and has been known for his color field painting, especially during the 1960s when Abstract Expressionism came of age. As an artist who has experimented with draped-painted canvas, he has also worked with iridescent acrylic, handmade paper, steel and plastic material. His large draped work, Yves Klein Blue, 2016, is the introductory work at the entrance of the Central Pavilion on the Giardini campus.

Sam Gilliam, Screen Models lll, 60 x 110, Mixed Material on Canvas, 2014

An example of a hardedge canvas, Screen for Models III, he uses striped off tape, letting color bleed through various levels of under-painting. He has said he is inspired by everything; his own history, the books he reads, the lifetime of traveling and the examples set by artists who came before. In a recent interview, he talks of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, Monet’s Water Lilies and Countee Cullen, whose poem Yet Do I Marvel provided the title of the new piece for the National African American museum. Sticking to one style, Gilliam says, never struck him as a good idea. “There are theories in art, just like in music,” he explains. “You switch from Little Jimmy Dickens to Bob Dylan and Miles Davis to Art Blakey.” Gilliam received his B.A. in fine art and his M.A. in painting from the University of Louisville in Kentucky. He has taught at the Corcoran School of Art, the Maryland Institute College of Art and Carnegie Mellon University.

On the Giardini campus, and exclusively representing the United States is Mark Bradford, at the U.S. Pavilion. While many pavilions have multiple artists’ work, Bradford is the artist selected to represent the United States at the 2017 Venice Biennale. The multi-room installation is a narrative that reflects on the artist’s trajectory, using everyday materials that embody social meaning. Tomorrow Is Another Day, reveals how individual lives are also history in the best sense of the word. Upon entrance, we are confronted with the first space being occupied by a bulbous mass that hangs from the ceiling with a red and black surface made of layering commercially printed-paper and blasting it with a pressure hose. Spoiled Foot pushes the viewer to the periphery of the room, leaving the viewer literally on the margins, inviting human touch.

Mark Bradford, Spoiled Foot, Mixed Materials 2016

Mark Bradford, Go Tell It to the Mountain, Mixed Material, 2016

The African American artist, best known for his large-scale abstract paintings that examine the class, race, and gender-based economies that structure urban society in the United States, Bradford’s richly layered and collaged canvases represent a connection to the social world through materials. Bradford uses fragments of found posters, billboards, newsprint, and custom-printed paper to simultaneously engage with and advance the formal traditions of abstract painting. Mark Bradford was born in 1961 in Los Angeles, where he lives and works. He received a BFA (1995) and MFA (1997) from the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia.

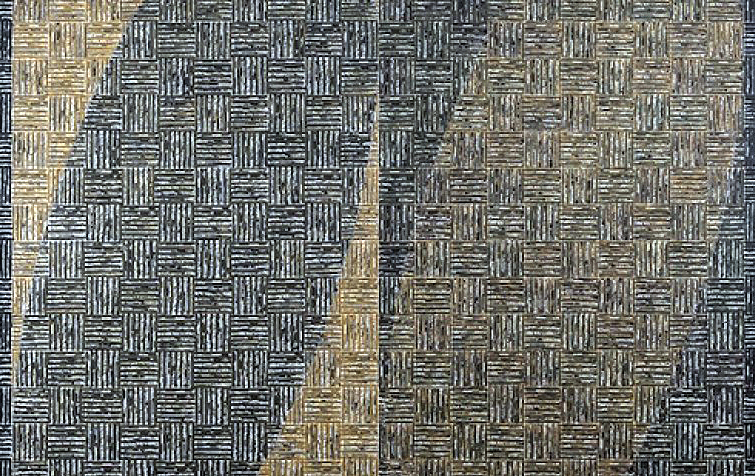

McArthur Binion, Installation image, courtesy of the Detroit Art Review

I was surprised to learn the McArthur Binion attended Wayne State University for his BFA in 1971 just as I completed my graduate work there. He moved on to complete his MFA at Cranbrook Academy, the first African American to do so and had a solo exhibition at the Detroit Institute of Arts. In 1973 Binion moved to New York and was soon curated into a group exhibition by Carl Andre at the Irving Sandler Gallery. In the early 90’s, he moved to Chicago to teach at Columbia College, and in isolation from the public, developed his emotionally based abstract paintings. Since 2003, Binion has been producing his DNA series, using a kind of geometric grid rigor with a minimal approach to abstraction. His childhood began in Macon, Mississippi, where he began picking cotton at the age of three and was one of eleven children. It was moving to Detroit to help his family survive that made his abstractions personal. He says in his statement, “I’m making abstraction personal. It’s taken me fifteen years to learn how to do it. Painting and sculpture are an old man’s game. To call yourself an artist, you have to earn it.”

McArthur Binion, DNA Black Series, 2015

Like many successful artists that fit the modernist profile, Binion makes work that is a study in oppositions: line and shape, figure and ground, image and abstraction, copy and original, color and black & white. His modus operandi is to somehow magically blend an assault of binaries into a single, unified emblem of the unique and complicated self.

Taus Makhacheva, Tightrope, Video Projection, 58m, 2-15

Taus Makhacheva, Tightrope, CU Angle, 58m, 2015

Among the sea of work at the Biennale, there were many video projected images and cinematic creations. I have selected one here by the artist Taus Makhacheva, born in Moscow, Russia who has a background in film-making. In her video, Tightrope, 2015, she records an activity from several angles, enough to convince you this is not a green screen performance against a live action background. The professional tightrope walker Rasul Abakarov carries 61 paintings, one at a time, from one side of a ravine to another, over an expanse of about a hundred feet and elevated many times more. Makhacheva is a Russian artist trained in London and mostly living in Dagestan where she explores the tension between tradition and modernity. Most of her work is performance-based, as she analyzes the body as a supporting structure, often challenged in off-limits situations. Makhacheva was born in Moscow in 1983. She studied at London College of Communication and the University of the Arts London. In 2007, she completed a BA program in Contemporary Art at Goldsmiths, University of London. In 2006, she graduated in World Economics from the Russian State University for the Humanities.

Tom Parish, In My Solitude, Oil on Canvas, 2015 Image Courtesy of the Artist

There are fifteen satellite shows to see during a visit to the 2017 Venice Biennale. One is the solo exhibition at the Madonna dell’Orto, Il Polso dell’Acqua, by Detroit artist Tom Parish. Nestled away in the neighborhood of Cannaregio, is the fifth exhibition for the Detroit artist, whose work continues to capture the urban water-laden landscape of Venice. The longtime Professor Emeritus of painting at Wayne State University in Detroit, journeyed to Venice some thirty years ago to discover subject matter that filled his curious and esthetically provocative imagination. For years his painting developed as architectural abstraction, with a formality that includes the ancient buildings juxtaposed to water and light. Parish’s recent work, on display in Venice, In My Solitude, combines his strengths: a composition that stretches out spatially and draws on elements of abstraction, and his command of painting the reflection-struck water swirling in the turbulent canals. There have been four major exhibitions of Tom Parish’s Venice work, one in Chicago in 2010 at the Gruen Gallery, and three in Venice, Italy. This new work – Il Polso dell’Acqua – is the fifth exhibition and the second at the historic Cloister of the Church of the Madonna del Orto in Cannaregio, Venice.

The Viva Arte Viva, 2017 Venice Biennale, in a world full of conflicts, where art bears witness to the most precious part of what makes us human. It is the ultimate ground for reflection, individual expression and freedom. The fine art presented is the favorite realm of dreams and utopias, a catalyst for human connections that roots us in both nature and the cosmos. Many see art as the last garden to cultivate above and beyond trends and personal interests. It stands as an unequivocal alternative to indifference. The role, the voice and the responsibility of the artist are more crucial than ever before within the framework of contemporary debates. It is in and through these individual initiatives, like the 2017 Venice Biennale, that we find the hopes and dreams of tomorrow.