Visual Citizenship, installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2020. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography.

The exhibition Visual Citizenship, on view at Michigan State University’s Broad Art Museum through December 26, is a considered show that comprises politically-charged prints and photographs that snugly fill the museum’s trapezoidal Collections Gallery. Its title comes from scholar, author, and filmmaker Ariella Azoulay, who argues that image-viewing is an active civic engagement, and Visual Citizenship explores the implied moral, ethical, and civic questions and obligations presented when a viewer confronts images, particularly images of injustice. The show is thoughtful, timely, and visually satisfying, and it includes artists whose names carry some real weight in the art-world, such as Kathe Kollwitz, William Hogarth, Francisco Goya, and others.

The advents of photography and printing democratized the image to a degree unparalleled until the age of the internet. They’re both relatively inexpensive media, and they don’t rely on moneyed and powerful patrons. Furthermore, photos and prints are easily reproduceable, and together they helped introduce a new visual language of civic and political discourse.

Francisco Goya wasn’t the first artist to harness printmaking to document social and political injustice, but he’s certainly among the most famous. His series of just over 80 prints which comprise his Disasters of War relay in first-person perspective and with unrelenting honesty the gritty and violent events that transpired when Napoleon’s army invaded Spain. The show’s informational panels aptly compare Goya’s etchings to the photographs captured by a modern-day war correspondent. On view is an etching from his Disasters, showing hangmen leading prisoners to a makeshift scaffold where several dead bodies already swing. There are also several etchings from his satirical Follies series. These images, never published in Goya’s lifetime, are freighted with dark and surreal imagery that seems to anticipate by a hundred years the style of the early 20th century symbolists. Goya’s work is rarely pleasant, but it’s a welcome foil to much of the fawningly polite Napoleonic propaganda produced by the likes of Jacques Louis David or Antoine-Jean Gros.

Duro es el paso! (The way is hard!), from The Disasters of War, 1810-14. Etching and aquatint, 9 1/2 x 12 7/8 inches. MSU purchase, funded by the MSU Development Fund 64.76

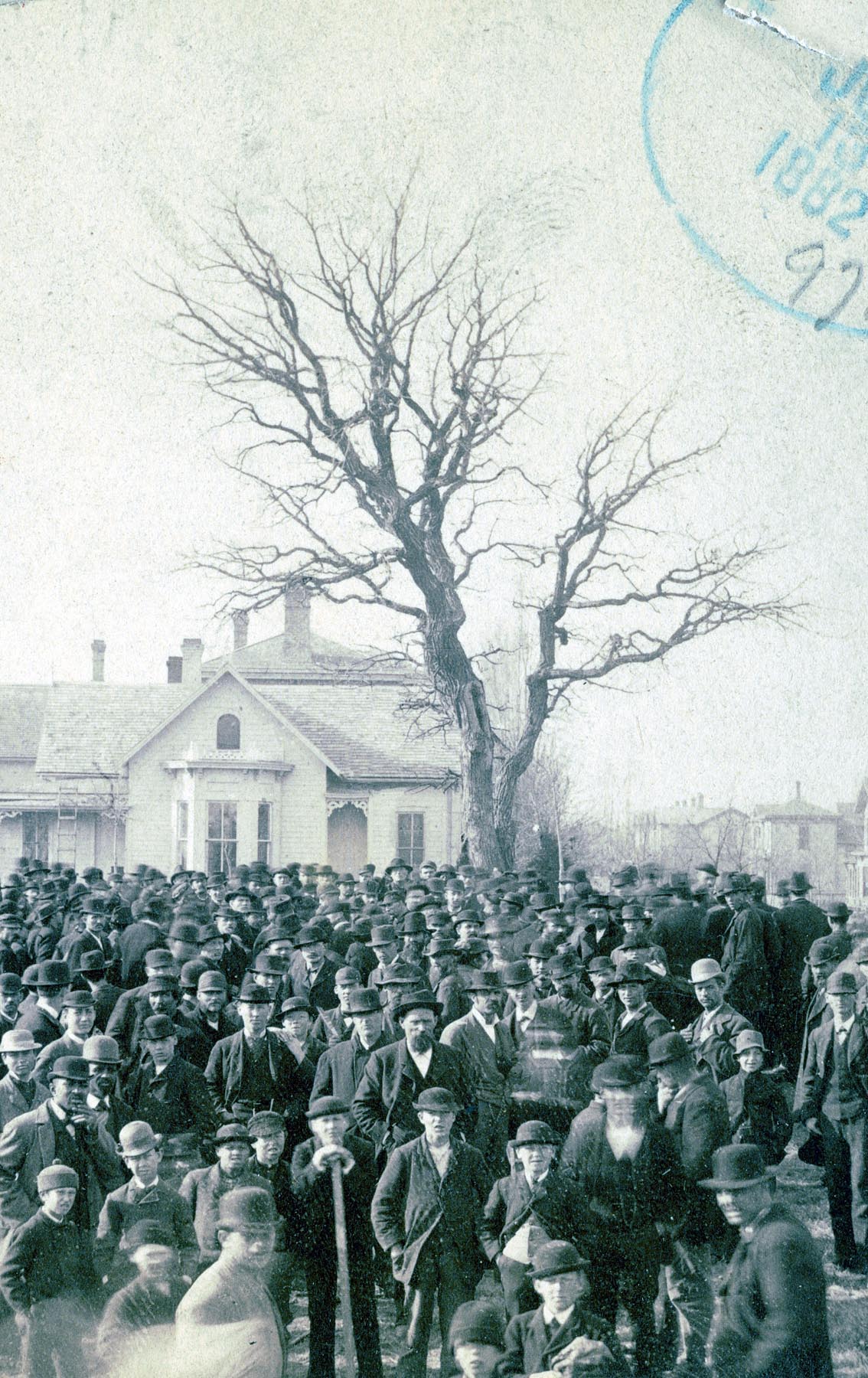

Perhaps the most arresting and uncomfortable ensemble of images in the show is the Erased Lynchings series by conceptual artist Ken Gonzales-Day. Gonzales-Day scanned images from actual postcards spanning from 1870 to 1940, all of which depicted photographs of the lynching of Lantin Americans, African Americans, Native Americans, and Asian Americans. He then digitally erased the victims, leaving only the spectators, who now become the subject of the image. The series addresses the role that bystanders and spectators play during social and political atrocities, and also the erasure of uncomfortable moments from our national narrative.

Erased Lynchings, installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2020. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography.

Lynching of Frank MacManus, Minneapolis, MN, 1882, from Erased Lynchings 2006-2019. Archival inkjet print on rag paper mounted on cardstock, 6 x 4 ½ inches. MSU purchase, funded by the Nellie M. Loomis Endowment in memory of Martha Jane Loomis, 2019.17.1-5

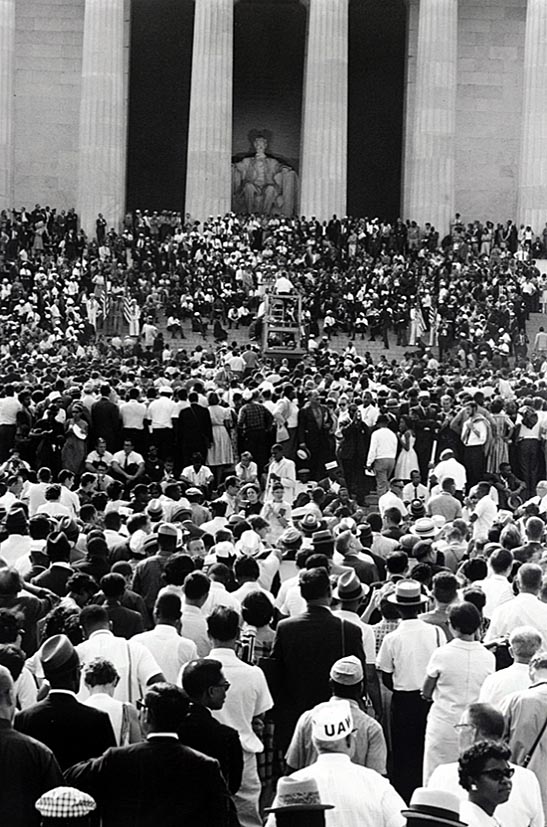

A generous selection of photographs of significant political marches, rallies, and protests highlights the role that documentary photography played in making people aware of the Civil Rights Movement, perhaps something easily taken for granted now that anyone with a smartphone and a social media account is a potential lay-photojournalist. These images include an ensemble by Leonard Freed, a photojournalist whose seminal work Black in White America (1968) documented the Civil Rights Movement with sensitivity and empathy, emphasizing the humanity of his subjects rather than the acts of violence and brutality they endured—the reverse of what Susan Sontag referred to in On Photography as the “atrocity exhibition,” which have a danger of becoming counterproductive to their cause. Here, a selection of Freed’s photographs variously document a civil rights protest in Brooklyn, the historic 1963 March on Washington, and the 20th Anniversary March on Washington in 1983.

1963, Washington D.C., USA (March on Washington, 8-28-’63), 1963. Photograph 11 x 14 inches. Courtesy Special Collections, MSU Libraries, Michigan State University

Finally, a quartet of engravings by William Hogarth adds some levity to the exhibit, as Hogarth’s wry, satirical works always tend to do. His characteristically tongue-in-cheek series Humours of an Election, based on an actual 1754 Oxfordshire election, implicates both the Whigs and the Tories in trying to hijack the election through any means necessary. Hogarth’s humorous approach to political critique is about as far from Goya’s nightmarish visions as one could possibly get, though both artists certainly shared a jaundiced perception of those in political power.

Four Prints of an Election: Plate II, Canvassing for Votes, 1757. Hand-colored engraving, 15 3/4 x 21 1/4 inches. MSU purchase 64.16

Visual Citizenship is a rewarding show, and each vignette of photographs or prints could easily be the starting point for a subsequent exhibition. It’s certainly relevant and timely, and not just because this happens to be an election year. After all, in the age of social media, the smartphone, and the viral video, images have become the primary way we gather news and process information, which certainly seems to underscore Ariella Azoulay’s original point that image-viewing is a civic act.

MSU Broad – Visual Citizenship, on view at Michigan State University’s Broad Art Museum through December 26, 2020