Nick Doyle, Please Let me Go, 2022, collaged denim on panel, 90” x 125” (belt), 11” x 36” (lighter), 72” x 15” (spoon) All photos: Adam Reich

The perils and attractions of consumption driven by the dynamics of corporate greed—when what we are conditioned to want might just kill us–forms the theme of Nick Doyle’s current exhibition Farmers and Reapers at Reyes Finn, on view in the gallery from June 4 – July 16. Doyle has chosen deceptively beautiful images to lure us toward the revelation that we may be the unsuspecting victims of our own desires.

In his previous show with Reyes Finn, Paved Paradise, the artist examined and seemed to celebrate—or at least feel nostalgia for–the assumptions inherent in the American Dream of limitless expansion and endless possibility. But with Farmers and Reapers, his vision has sharpened and darkened to tell a cautionary tale about the perils of falling for the false promises of capitalism. Or as Doyle says in his artist’s statement:

Today, as we experience an opioid epidemic, everything has become a drug. Social media, advertisement, market research: all born out of attempts to create false desires in a population with no actual resolution to those desires, only a constant cycle of momentary satisfaction that intends on keeping us locked in a state of perpetual, hankering consumption.

Of course, Doyle’s subtle jeremiad wouldn’t resonate with his audience if the artworks he has created were not attractive. And they are. His beautifully crafted and carefully constructed images of pretty flowers, shiny cutlery and glittering disco balls—even his wall-mounted portrait of a black garbage bag containing who-knows-what—are (sanctioned) pleasures for the eye, given force by their titles. Hence the disco ball is entitled Death Star, his lush bouquet of poppies is called A Siren’s Symphony. Even as we viscerally feel the attraction, we are brought up short by the artist’s ominous caveat.

Nick Doyle, Body at Rest, 2022, collaged denim on panel, 51” x 40”

Nick Doyle, Siren’s Symphony, 2022, collaged denim on panel, 95” x 89”

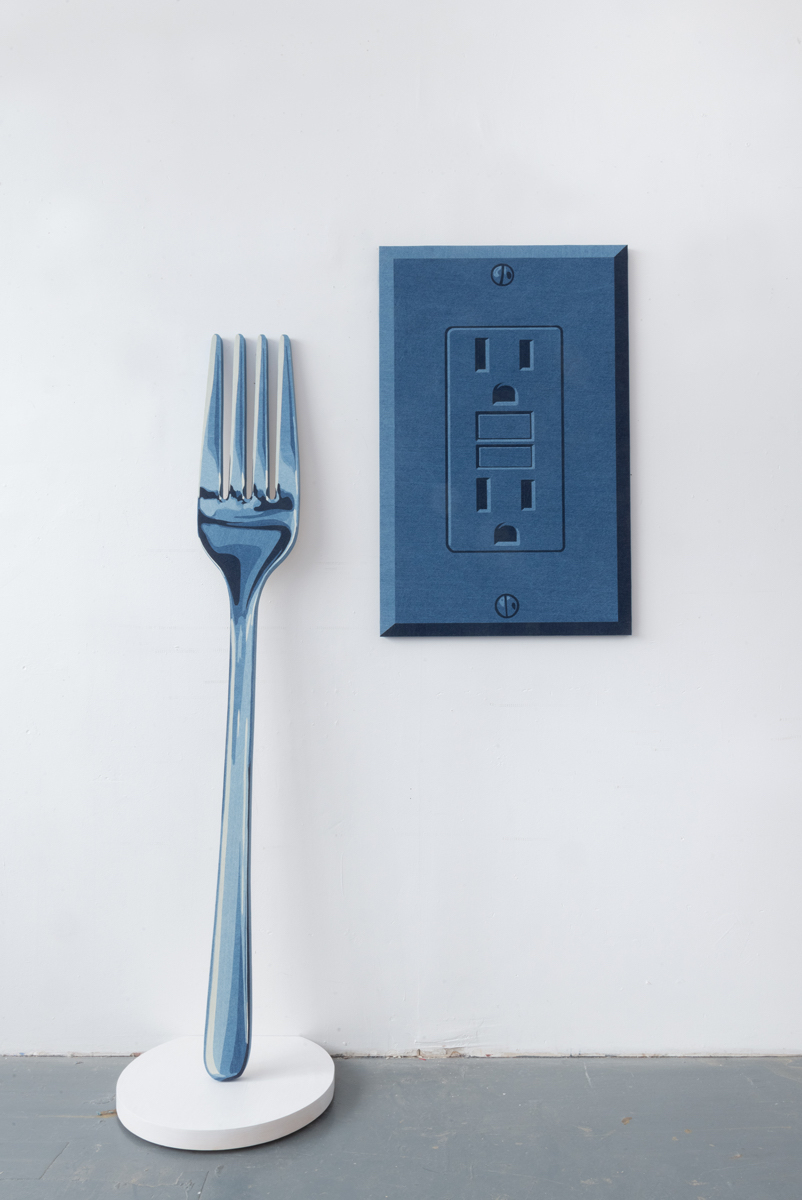

All except one of the artworks in this exhibition are handmade out of quotidian denim, the fabric of the common man and Doyle’s signature material. The artist has meticulously cut and laminated shapes reminiscent of paint-by-numbers kits to silhouettes made of shaped medium density panels. Individual pieces like Cold Sweat, an oversized, pink, melting popsicle, and Morning Shake, a cup of coffee surrounded by a spill, are disturbingly specific images of personal addiction. Please Let Me Go combines magnified images of drug paraphernalia—a belt, a spoon, a cheap lighter—in an unholy trinity. It’s impossible to look at Putting Two and Two Together without imagining the sensation of physical shock that comes from sticking a fork in an electrical socket.

Nick Doyle, Putting Two and Two Together, 2022, collaged denim on panel, 72” x 10” (fork), 40” x 25”

The poppies in Farmers and Reapers introduce an unexpected lyrical note—and possibly a sly irony–into Doyle’s visual vocabulary, which up to now has consisted mostly of manufactured objects. Doyle employs images of mass-produced items–still ubiquitous, pandemic-related supply chain issues notwithstanding–as a kind of shorthand for capitalism and colonialism, and in a broader sense, American individualism and toxic masculinity. The opioid-producing poppies, sourced mostly from Southeast Asia and Latin America, might represent the revenge of the third world, which has now created a reciprocal addiction.

Nick Doyle, Cold Sweat, 2022, collaged denim on panel, 67” x 47”

Only one of the artworks in Farmers and Reapers is a three-dimensional miniature similar to those that have appeared in Doyle’s previous shows. Gone, a doll-size, perfect replica of a hospital bed, is made of wood and comes complete with rumpled hospital sheets and blanket. It is a poignant comment on the ultimate price that many will pay for their addiction. Positioned on a low pedestal, we see the bed from above, the ghostly point of view of a departing soul. The sensation of looking down is shocking, but already we feel the remoteness that must accompany the passage of the recently deceased.

The undeniable attractions of the artworks in Farmers and Reapers heighten the emotional charge of their dark subtext by simultaneously seducing and repelling the viewer. These poppies and mirror balls, these garbage bags and spoons and forks, together constitute both a warning and a lament for the destructive yet often unacknowledged power of invisible economic forces. As Reyes/Finn partner Bridget Finn says of the artist, “He opens conversations on addiction, destruction and capitalistic greed and the ways in which they are opposed to the fallacy of the American Dream, thus using the fiber of American culture to craft its critique.” With Farmers and Reapers, Nick Doyle seems intent on raising awareness of the traps laid by malign elements as the first step toward moving beyond them.

Nick Doyle, Gone, 2022, maple, cotton, wax, 2022, 13” x 22” x 11”

Nick Doyle: Farmers and Reapers at the Reyes/Finn Gallery through July, 16. All images courtesy of the artist and Reyes/Finn, Detroit