Marisol, The Party, 1965-1966, installation, Toledo Museum of Art, 15 figures, 3 wall panels, painted and carved wood, mirrors, plastic, television set, clothes, shoes, glasses and other accessories. Toledo Museum of Art Collection, photo: K.A. Letts.

It’s far from common for a major artist’s retrospective to drop at Detroit’s doorstep rather than on the coasts, but “Marisol: A Retrospective,” at the Toledo Museum of Art has just landed like a thunderclap, shattering previous dismissive evaluations of the artist’s work and life. Until June 2, anyone with eyes and transportation should be beating a path to this paradigm-shifting survey of a boundary-breaking artist. For museum visitors who may previously have seen only one or two of Marisol’s pieces, this exhibition will be a revelation.

Born in Paris in 1930 to an elite Venezuelan family, Maria Sol Escobar spent her early childhood traveling between the U.S. and South America. Despite the family’s comfortable circumstances, Marisol suffered early trauma when her mother, Josefina, committed suicide. In response, she began a prolonged period of silence, a gesture that became a habit. Throughout her life Marisol maintained a Garbo-esque mystique which both intrigued and alienated her audience and may have contributed to later critical neglect of her work.

Marisol arrived in New York in the 1950’s where she studied at the Art Students League, the New School for Social Research and the Brooklyn Museum of Art School. Several works from this early period, during which she was influenced by Pre-Columbian clay figures, as well as Rodin’s Gates of Hell, are on display in the museum’s entry gallery, and along with a comprehensive timeline of her life, provides an introduction to the more iconic work that follows.

Although Pop art, with which Marisol was later strongly associated, was in its early stages, her work was first noticed and shown by Leo Castelli in 1957. Spooked by the sudden attention, the artist left for Rome in 1958 and stayed away for two years, a pattern of alternating visibility and absence that repeated itself several times throughout her life. Upon returning to New York in 1960, Marisol found herself drawn to Andy Warhol and his circle. She began to work in assemblage, combining found, carved and drawn components in sculptures that came to define her singular style. She was a sensation, both artistically and socially. Warhol included her in two of his films, and she was often photographed for Glamour, Harper’s Bazaar, the New York Times Magazine, and Vogue. Her exotic good looks made her both a victim and a beneficiary of the casual sexism of the time.

Marisol Baby Girl, 1963 wood and mixed media overall: 74 x 35 x 47 inches (187.96 x 88.9 x 119.38 cm) Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York Gift of Seymour H. Knox, Jr., 1964

The central gallery of Toledo Museum of Art, in which the most iconic of Marisol’s sculptures are displayed, shows Marisol’s art practice during the 1960’s at the most critically successful period of her career. The quantity and quality of the work is breathtaking. The artist’s output from this period is both intensely personal and often baldly political, formally inventive yet thematically transparent. Though Marisol’s career pre-dated the second-wave feminism of the seventies, and she was never a fully “feminist” artist, many of her pieces are filtered through an unmistakable female identity.

Two of the most celebrated sculptures on display from this period are the enormous Baby Boy (1962-1963) and Baby Girl (1963). These sentimental yet monstrous infants–Baby Boy is 8 feet tall, and Baby Girl, if standing, would reach 10 feet in height—are psychologically fraught comments on the dominant role children play in society’s definition of women as mothers. Each child clutches a tiny representation of the mother, both of whom are likenesses of Marisol herself. The artist also said that Baby Boy, who is wearing red, white and blue, was a representation of the United States as an infant, heedlessly throwing his weight around on the world stage.

Marisol, Mi Mama y Yo, 1968, wood and mixed media, 74” x 35” x 47” Buffalo AKG Museum, Gift of Seymour H. Knox, Jr., 1964 (K1964:8) © Estate of Marisol / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photo: Brenda Bieger, Buffalo AKG Art Museum

Though it would be hard to pick out a favorite piece among the many masterworks in the gallery, a few stand out. One is an installation with multiple figures, The Party, which coincidentally is in the Toledo Museum of Art’s permanent collection. A flock of fashionable ladies in mid-century formal attire– and all with Marisol’s face– gather for cocktails, a group portrait of social isolation. Marisol puts an even finer point on her alienation in a photograph taken by John B. Schiff in 1963. The real Marisol sits at a table with two 3-dimensional images of herself in Dinner Date. She is alone yet keeping herself company.

Marisol, Pope John 23, 1961, wood, mixed media, Abrams Family Collection, photo: K.A. Letts.

In many of her assemblages and installations, Marisol shows herself to be wickedly clever at mocking social pretension, political hypocrisy, and male privilege. Her assemblage Pope John 23 (1962) shows Marisol at her most deftly satirical. A barrel-clad pope sits astride a roughly knocked-together hobby horse, its head featuring the face of the artist, literally being ridden by the patriarchy. Marisol created sculptures of prominent political figures such as the Kennedy family, the British royal family and even Lyndon Baines Johnson, holding 3 small birds representing his wife, Lady Bird, and two daughters.

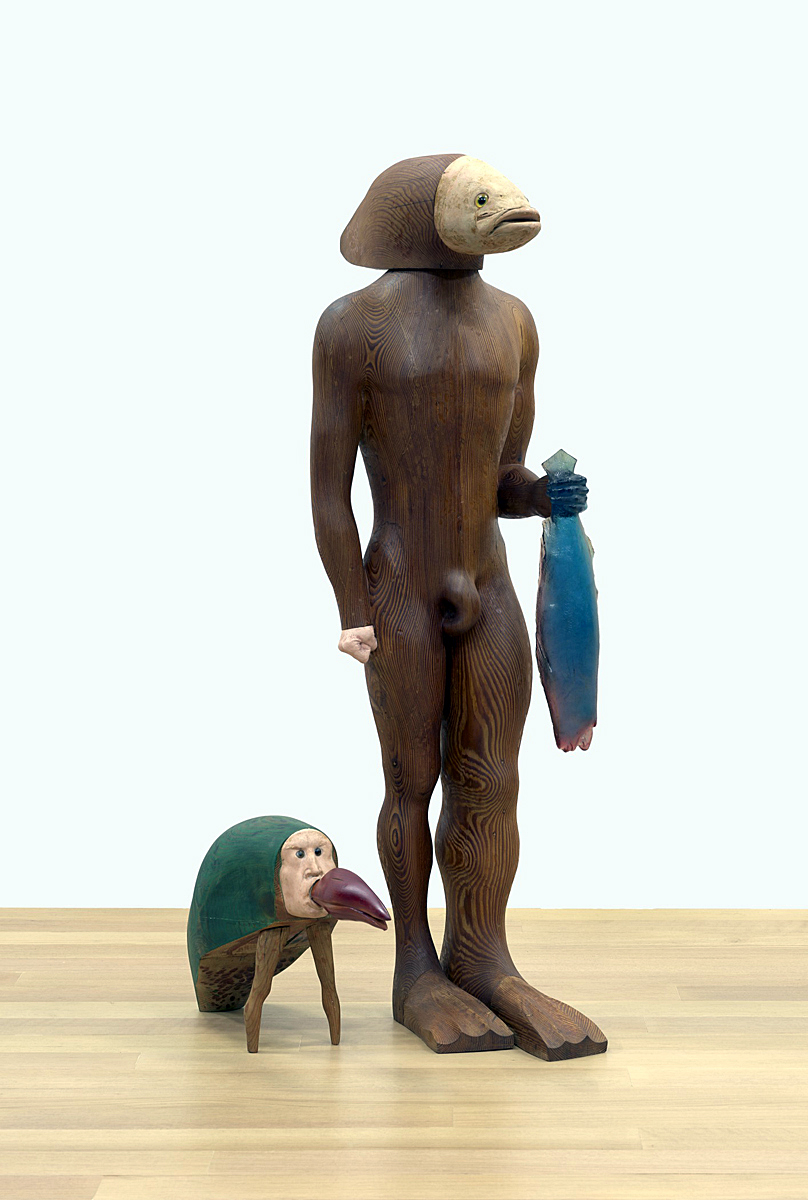

Marisol, The Fishman, 1973, Wood, plaster, paint acrylic, and glass eyes, 68.25 x 28 x 33.25, Buffalo AKG Art Museum Bequest of Marisol, 2016 (2021:37a-g) © Estate of Marisol / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photo: Brenda Bieger, Buffalo AKG Art Museum

At the height of her fame in the late 1960’s, Marisol once again abandoned the New York art world for Tahiti, where she took up scuba diving and spent several years creating a new body of work centered around environmental themes. The artworks in the penultimate gallery at the TMA are devoted to these misunderstood images and objects, which to contemporary eyes now seem prescient. Though Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” was published in 1962, and the first Earth Day was held on April 22, 1970, the destructive relationship of humans to the planet–and its implications–hadn’t fully registered with the cultural elite. The new work also had a surrealist edge that was at odds with art fashions of that moment such as conceptual art and post-minimalism. The glossily finished, figurative sculptures of fish she made and then exhibited in 1973 met with bafflement and critical rejection.

Marisol, John, Washington, and Emily Roebling Crossing the Brooklyn Bridge for the First Time, 1989, wood, stain, graphite, paint, plaster, Buffalo AKG Museum, photo: K.A. Letts

Marisol, Georgia O’Keeffe and dogs, 1977, graphite and oil on wood. 52.5 x 53 x 60.25” Buffalo AKG Art Museum Bequest of Marisol, 2016 (2021:44a-i) © Estate of Marisol / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photo: Brenda Bieger, Buffalo AKG Art Museum Marisol (Venezuelan and American, born France, 1930-2016

The final gallery in Marisol’s retrospective is filled with maquettes and examples of public art works the artist designed for North and South American sites. Her often controversial commissions featured historical and cultural figures such as the revolutionary Simon Bolivar , Father Damien(a Belgian born missionary to lepers in Hawaii), Mark Twain, Georgia O’Keeffe (and her dogs) and Queen Isabella. A particularly impressive piece is a model for a monument to John, Washington and Emily Roebling, builders of the Brooklyn Bridge, shown crossing for the first time. Unfortunately the final work was never completed.

After a period of relative obscurity at the beginning of the 21st century, Marisol was the subject of a traveling survey of her work in 2014, organized by the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art. The exhibition curator, Marina Pacini, stated at the time that Marisol was “an incredibly significant sculptor who has been inappropriately written out of art history.” Indeed, when the artist died in 2016, the headline for her obituary in the Guardian read “Marisol: The Forgotten Star of Pop Art.” This reductive assessment has begun to change through the efforts of the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, which received the artist’s estate and papers as a bequest. “Marisol: A Retrospective” is a welcome step toward the reassessment and rehabilitation of this neglected visionary.

Gallery Installation, Toledo Museum of Art, sculptures and photographs by the artist during the 1970’s, photo: K.A. Letts.

Marisol: A Retrospective is organized by the Buffalo AKG Art Museum (Cathleen Chaffee, Charles Balbach Chief Curator) in cooperation with several major museums, including the Toledo Museum of Art ( Jessica S. Hong, senior curator of modern and contemporary art.) Exhibition schedule: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Oct. 7, 2023-Jan. 21, 2024; Toledo Museum of Art, March 2-June 2, 2024; Buffalo AKG Art Museum, July 12, 2024-Jan. 6lm2025; Dallas Museum of Art, Feb. 23-July 6, 2025.

And a Bonus: Caravaggio!

For museum visitors who can make it down to Toledo before April 14, a small but fascinating collection of Renaissance masterpieces awaits. Four paintings by Caravaggio, on loan from The Kimball Art Museum (Fort Worth, Texas), the Wadsworth Atheneum (Hartford, Conn.), the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), and the Detroit Institute of Arts (Detroit) form the framework upon which the organizers of this exhibition build their survey of artworks from the Toledo Museum of Art’s own collection. Caravaggio’s influence is foregrounded here in paintings by Hendrik ter Brugghen, Artemesia Gentileschi, and Jusepe de Ribera, to name only a few.