If you’re local to the Detroit area, it’s well worth making the shortish trek north to visit the Saginaw Art Museum and Gardens. Located in the grand former home of a local lumber magnate, the SAM boasts a collection of European and American artworks from the last 200-plus years, plus a few pieces from elsewhere in the world. One gallery is devoted to the work of Saginaw native E.I. Couse, who studied under Bouguereau, and a rotating selection of prints from the museum’s collection is displayed in their library room. Of course, they feature special exhibitions as well. Two shows are up now; both are by local women artists, and both address family matters, though from different angles. Sabrina Nelson: She Carries runs through May 23, and Melissa Beth Floyd: Now What is on display through September 6.

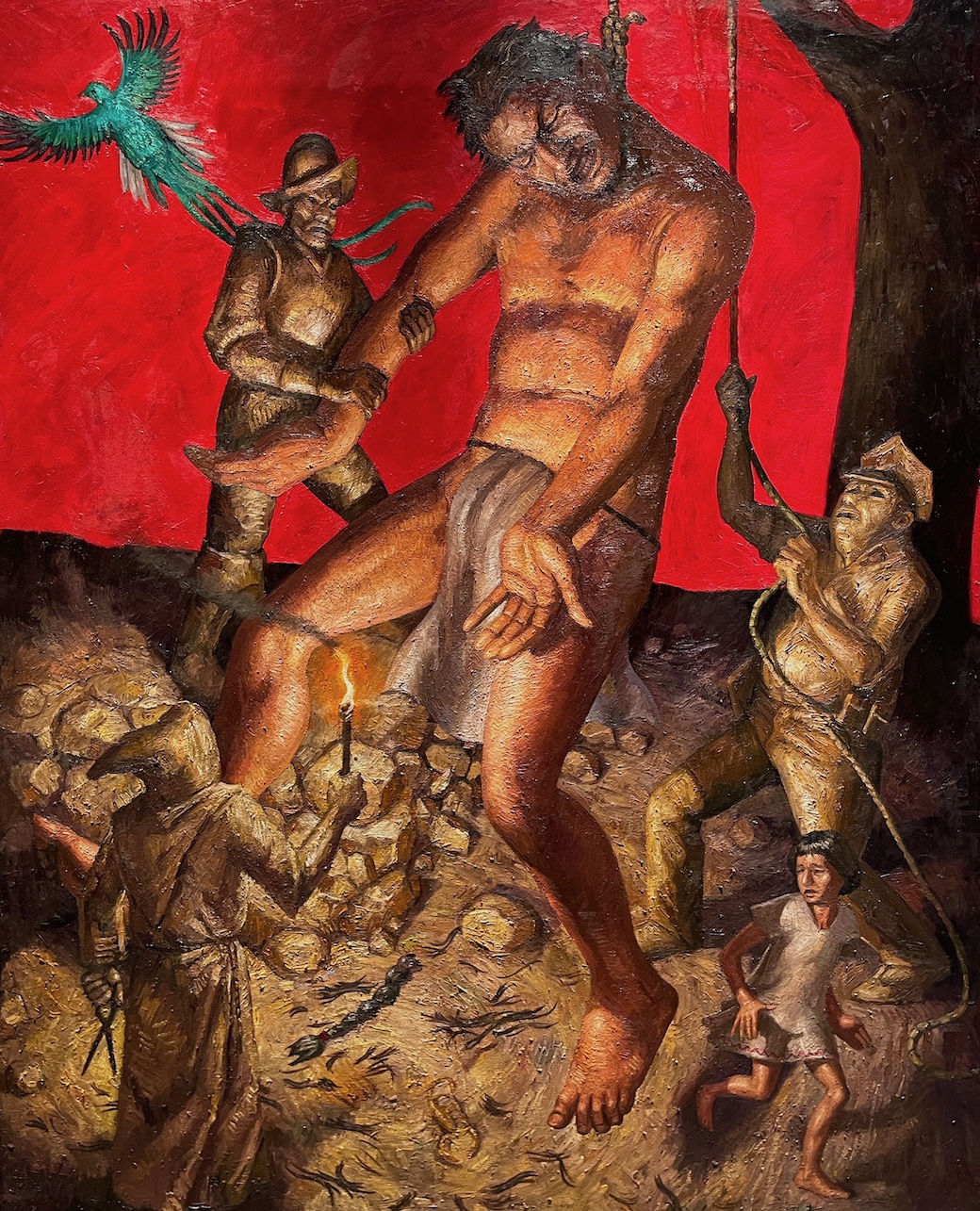

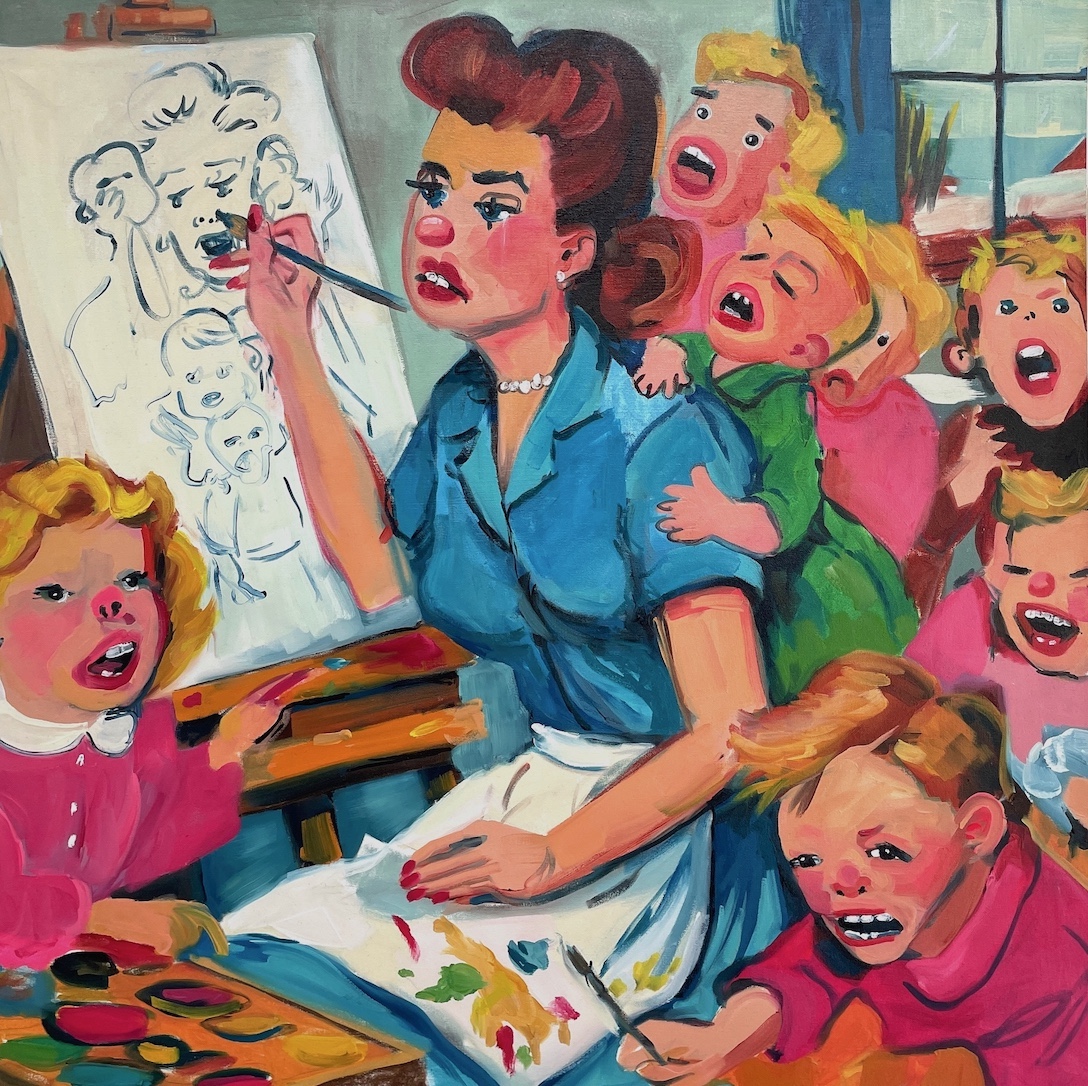

The Good Life, Oil on Canvas, 2025

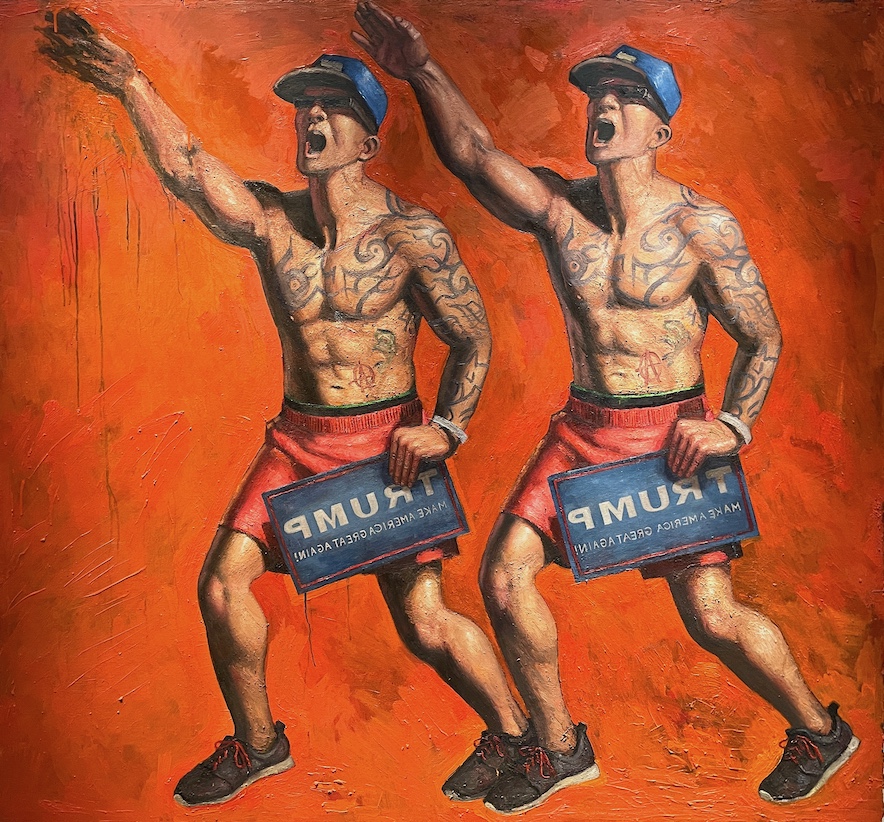

“Now What” sounds like it could have been the cheeky title of a mid-century survey show at MoMA. It definitely sounds like the exasperated grumble of a mother who just heard a loud crash come from her kid’s room — a mother who might rather be visiting MoMA, or working on her own art. Many of Cranbrook grad Melissa Beth Floyd’s paintings feature women dressed and coiffed in the style of archetypical white 1950s housewives, each having her dreams and desires thwarted, often by small armies of rambunctious children. Kicking against the chirpy idealism and starchy conformity of the ‘50s has been popular in America since… well, since the ‘50s. Humorists have frequently lampooned the century’s squarest decade, maybe to the point of cliché. But now that many of the retrograde attitudes of that age seem to be enjoying renewed popularity— the “trad wife” trend, the gross “pronatalist” movement, etc. — maybe the time is right again to evoke the imagery of the 1950s in order to comment on the current cultural climate.

One harried mother in a painting entitled The Good Life sits exhausted at her easel, beset by kids with toothy, mewling maws demanding her attention; on her canvas is a sketch of a scene not unlike the painting itself. The would-be artist wears a round red nose and eye makeup like the clowns in the pictures that decorated so many mid-century rec rooms. Floyd’s images are a sort of revisionist version of the ads and illustrations found in the Saturday Evening Post or similar magazines. Norman Rockwell might come to mind first, but Floyd’s work, with its lively compositions and deft brushwork, more closely resembles that of other members of the Famous Artists School, such as Ben Stahl or Al Parker.

Feeding Frenzy 2025, Oil on Canvas,

When Floyd’s women aren’t being mobbed by kids, they’re often being harassed by angry, Hitchcockian birds, as in Feeding Frenzy, in which a flock of seagulls descends upon a woman in a blue dress and broad-brimmed hat. Unlike in the horror movie, the birds’ motives here are obvious — they’re after the sandwich their victim is holding. Food is another recurring theme here, as Floyd’s women attempt to eat donuts, hamburgers, ice cream cones or, in one innuendo-heavy image, a large sausage. As aggressively hungry as her birds are, Floyd’s women can be just as ravenous, defiantly indulging their appetites when there are no avian threats to interfere with them. In Binge, a blonde woman digs into a spread of candy-colored pastries with a furious gusto, and the character in Brontosaurus Burger seems about to unhinge her jaw snake-style to swallow her supersized sandwich.

Binge 2024 Oil on Canvas, 2024

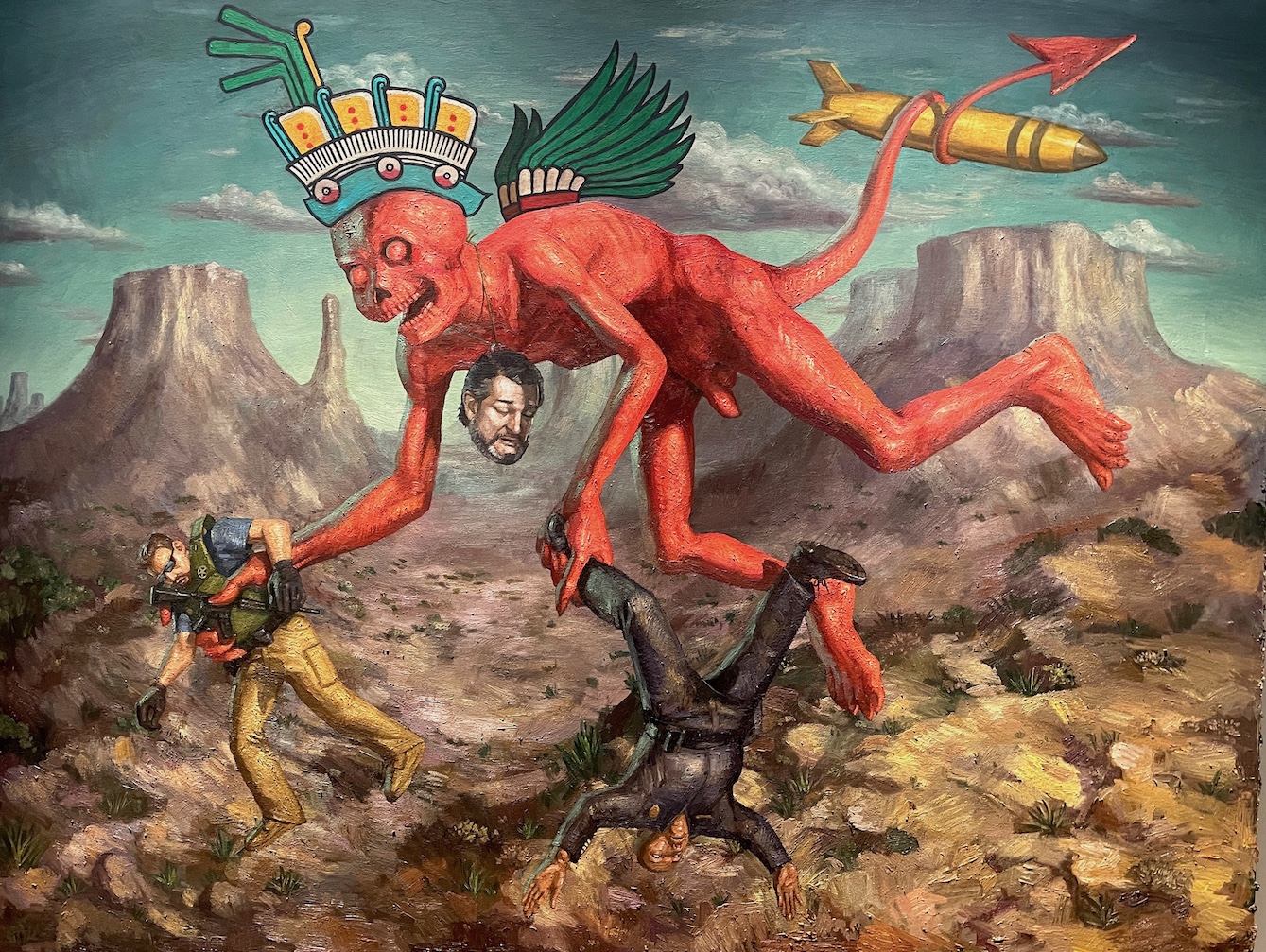

Far Enough, Oil on Canvas, 2025

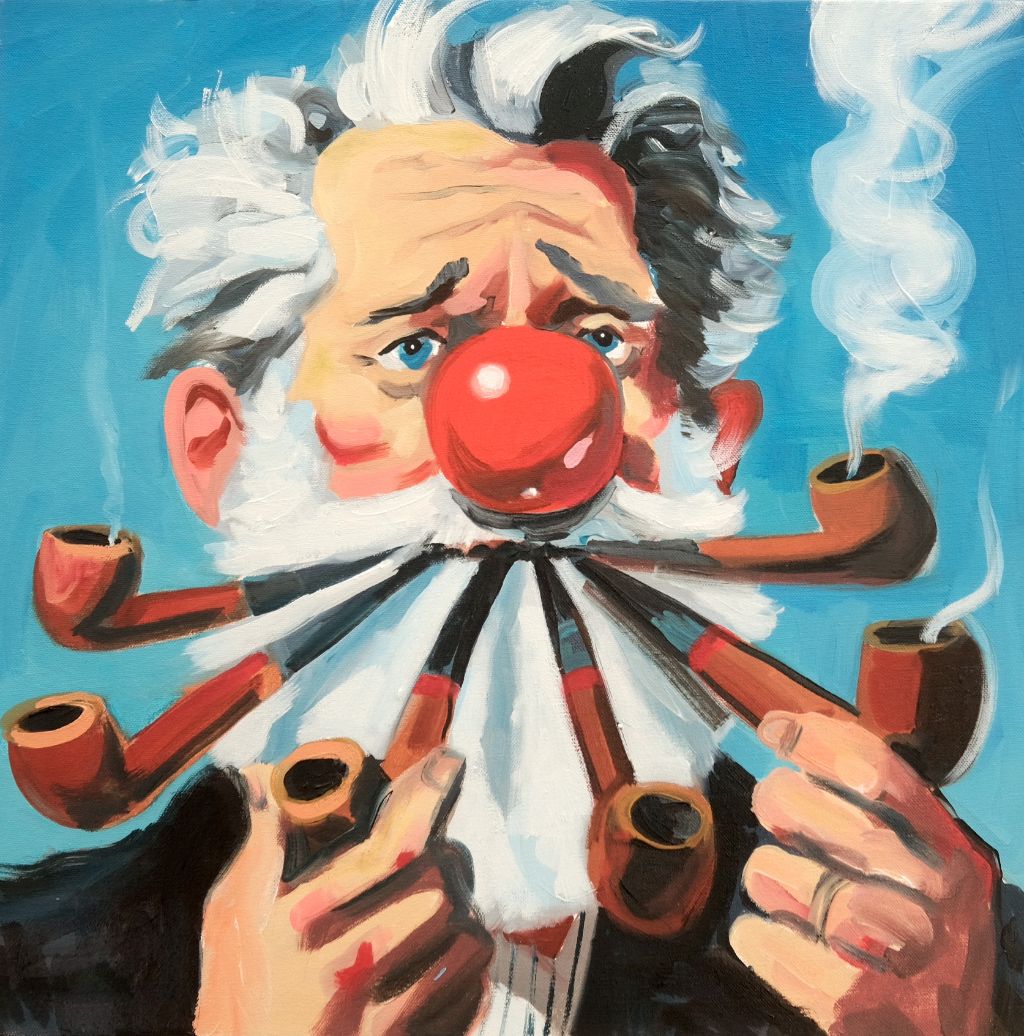

Men show up in Floyd’s paintings here and there, too. In Far Enough, a Brylcreemed, lantern-jawed guy in a pinstripe suit looks up at a looming mountain range from the puddle of mud he’s sitting in; Nature itself seems to have finally gotten tired of his nonsense and knocked him on his ass. And in Untitled (After Magritte), a bearded academic type with a red clown nose puffs away at six “ceci n’est pas une pipes” simultaneously, a humbling image that reminds this, ahem, arts writer to mention the wry humor that runs throughout this wonderful show.

Untitled (after Magritte) Oil on Canvas, 2024

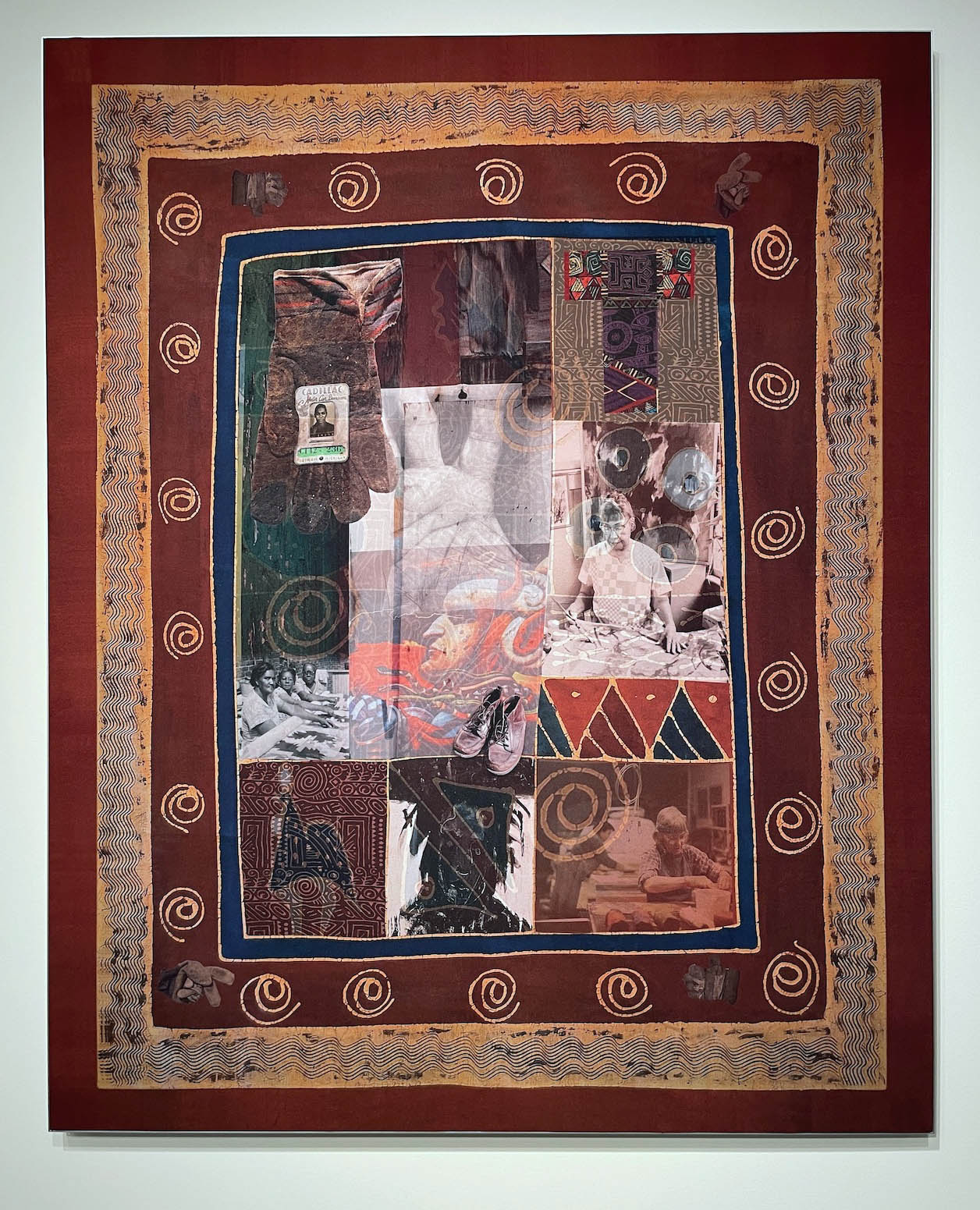

Song of Solomon 2:1, I am the Rose of Sharon Lily of the Valley Wax pencil and gel pen on paper 2025

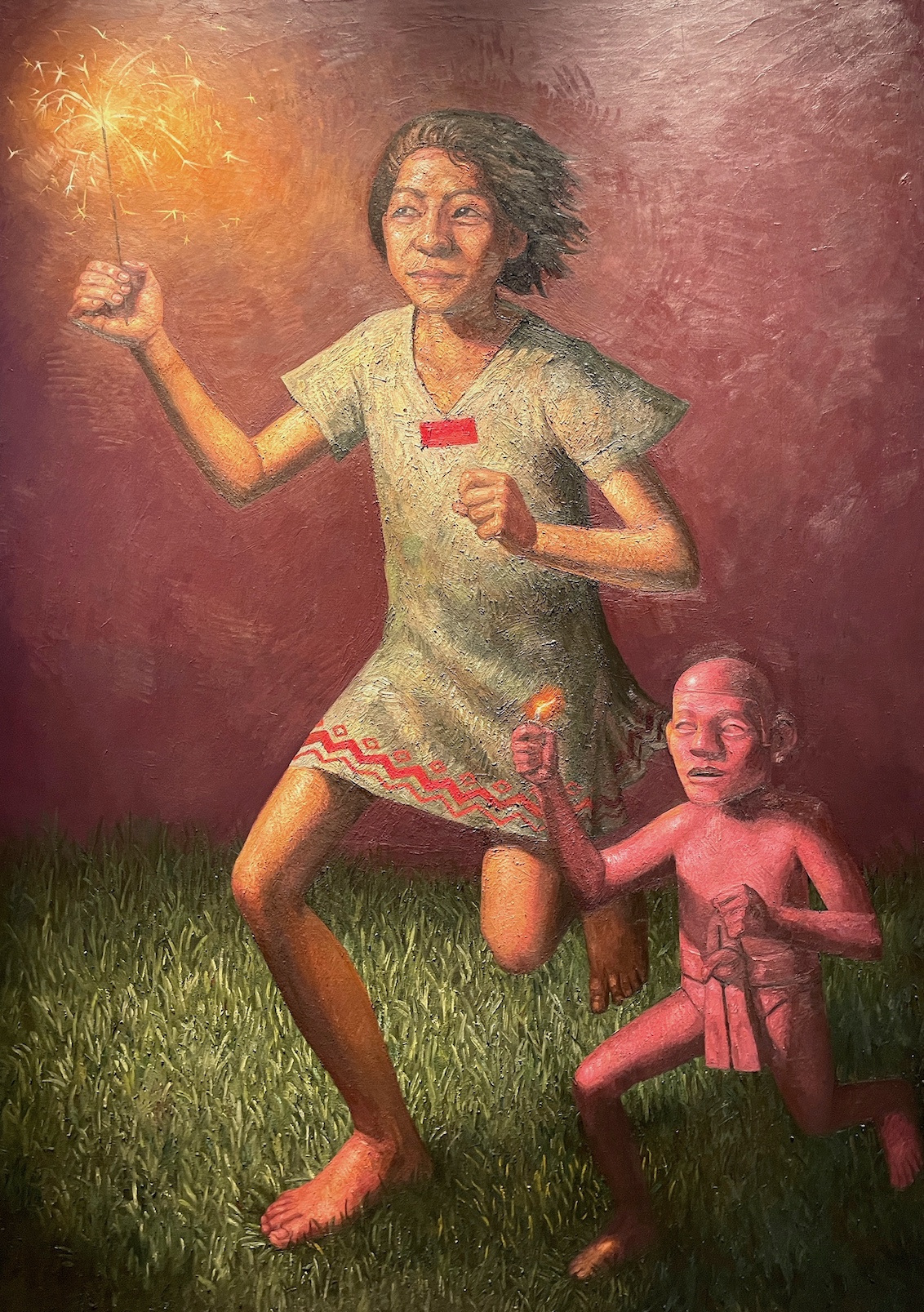

Sabrina Nelson takes on issues of female resilience and resistance as well, specifically regarding Black women, but in a more personal way — quiet, earnest, and no less powerful. Using watercolor, gel pens, and colored pencil, Nelson creates thoughtful and tender portraits of friends and family, multilayered images that include not just her subjects but their family members and ancestors — pictures within pictures in the form of framed photos, t-shirts, or sculptures worked into the compositions. (Paying tribute to loved ones in her art is an impulse Nelson has passed along to her son, the painter Mario Moore.)

The Gardener Wax pencil and gel pen on paper 2025

Plant life appears in many of Nelson’s portraits, lending another level of warmth to the images, but also gesturing to cultural or personal symbolism as well. For example, one portrait depicts a musician friend surrounded by Western and African instruments (she even wears a tambourine for a hat). The background is patterned with outlines of hibiscus flowers, a.k.a. the Rose of Sharon, as mentioned in the biblical Song of Solomon that lends the portrait its title. In a particularly beautiful drawing entitled The Gardener, a young woman cradles a bundle of collard greens, while okra blooms in the background; both vegetables are staples in traditional Black American cuisine. The subject of another portrait holds a sprig of St. John’s wort, a plant used in traditional medicine. Many of Nelson’s portraits are drawn onto black paper, making the jewel-like colors glow even more intensely. Others, such as 2022’s She Carried Her Sons, are drawn on white paper in muted tones that suggest old sepia or black-and-white photos; these are embellished with three-dimensional corsages made from doilies and dried flowers.

St. John’s Wart, McKinney

In her opening remarks on the show, Nelson describes a trip to Zimbabwe, during which she observed women, even quite elderly ones, carrying things — firewood, water, food, and children. The experience prompted her to consider what she and other women carry, in every sense — physically, but also emotionally, psychologically, and spiritually. (A short video recording of her remarks, as well as a longer one in which Nelson explains the show in more depth, are both available on the Saginaw Art Museum’s YouTube page.) It’s something Nelson wants museum patrons to contemplate as well. In the center of the room — near a collection of suitcases containing baby clothes, aprons and gloves, antique medicine bottles, and other traces of family history — is a small box with a sign asking, “What Do You Carry?” Visitors can write their responses on slips of paper and add them to the growing collection in the box — or, perhaps, keep them and carry them away, a souvenir of a day well spent at a fine Michigan museum.

She Carries, Installation image.

“Melissa Beth Floyd: Now What” and “Sabrina Nelson: She Carries” @ Saginaw Art Museum