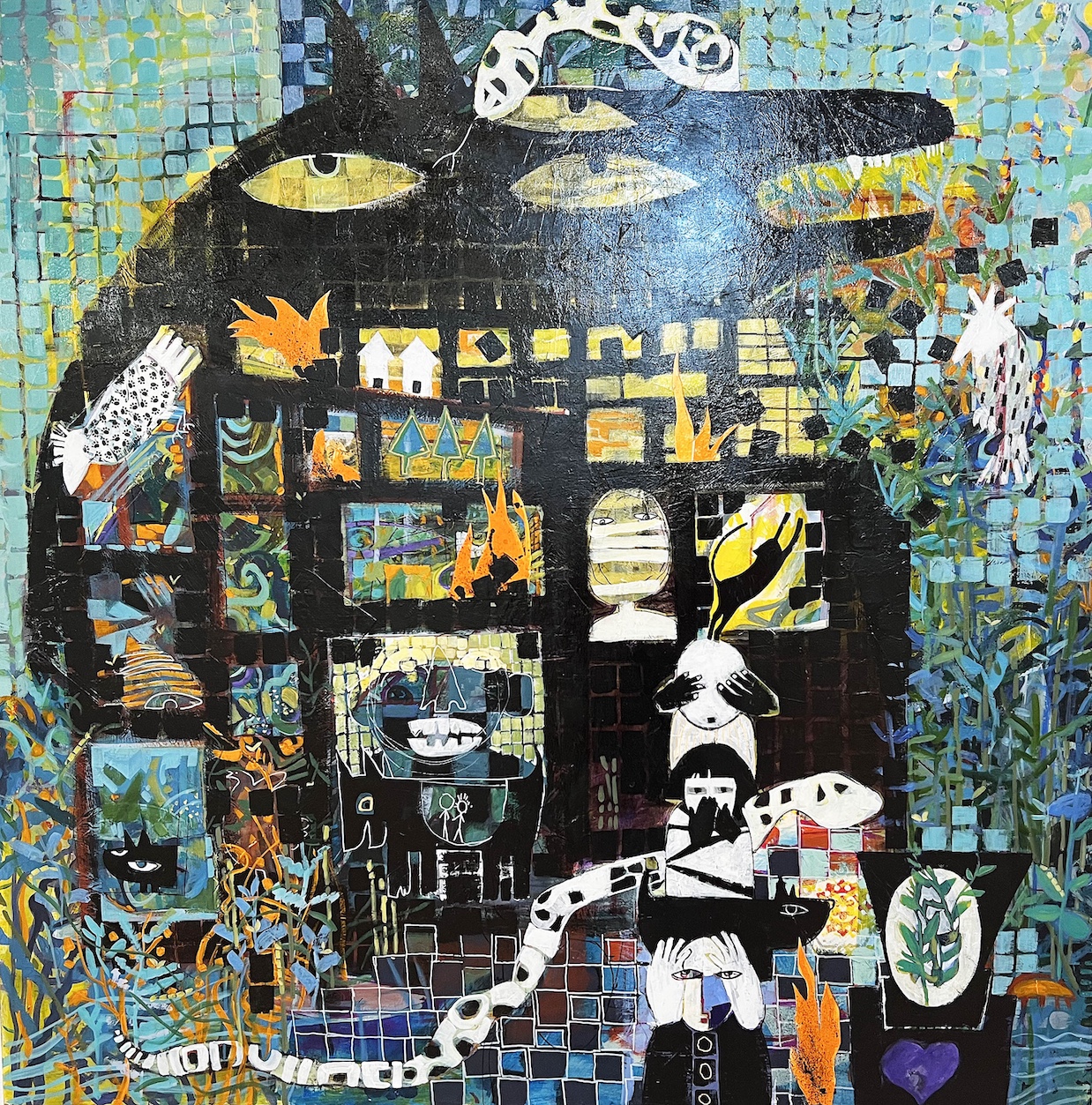

An installation shot of Jackson Wrede’s Menagerie at the Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center. It and a companion show, Descriptive Intuition by James Kaye, will be up through May 1.

Two lively shows by Michigan artists at the Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center up through May 1 — James Kaye’s Descriptive Intuition and Menagerie by Jackson Wrede — offer up a refresher course in the relative power of abstraction vs. figurative art. Side by side, the two exhibitions make for punchy viewing. Passing from one into the other is both stimulating and invigorating.

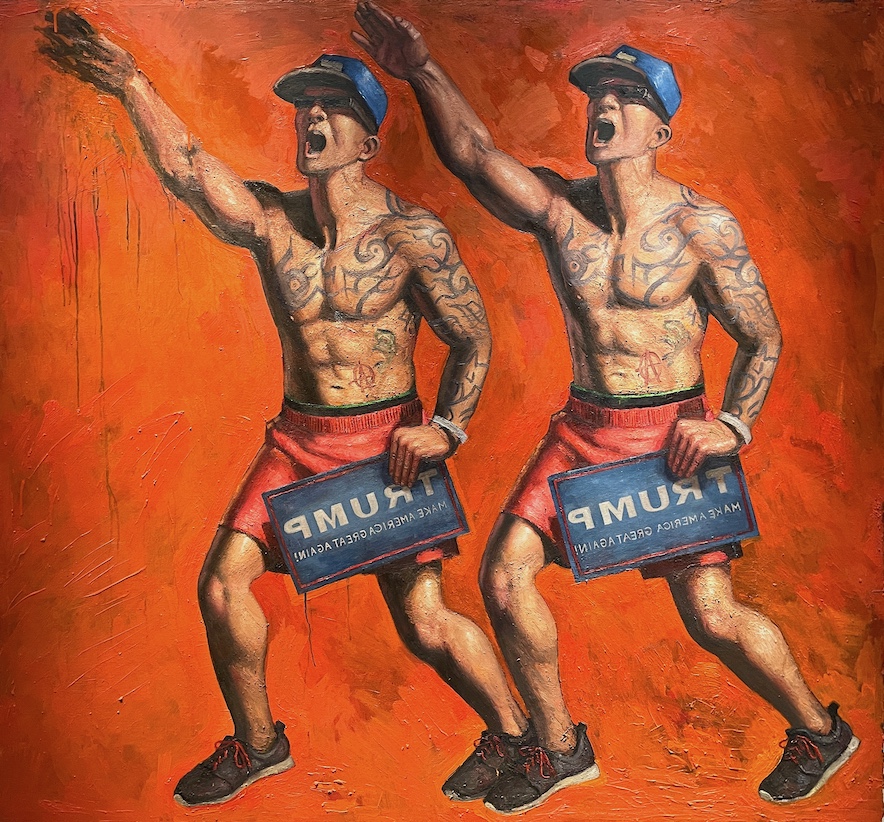

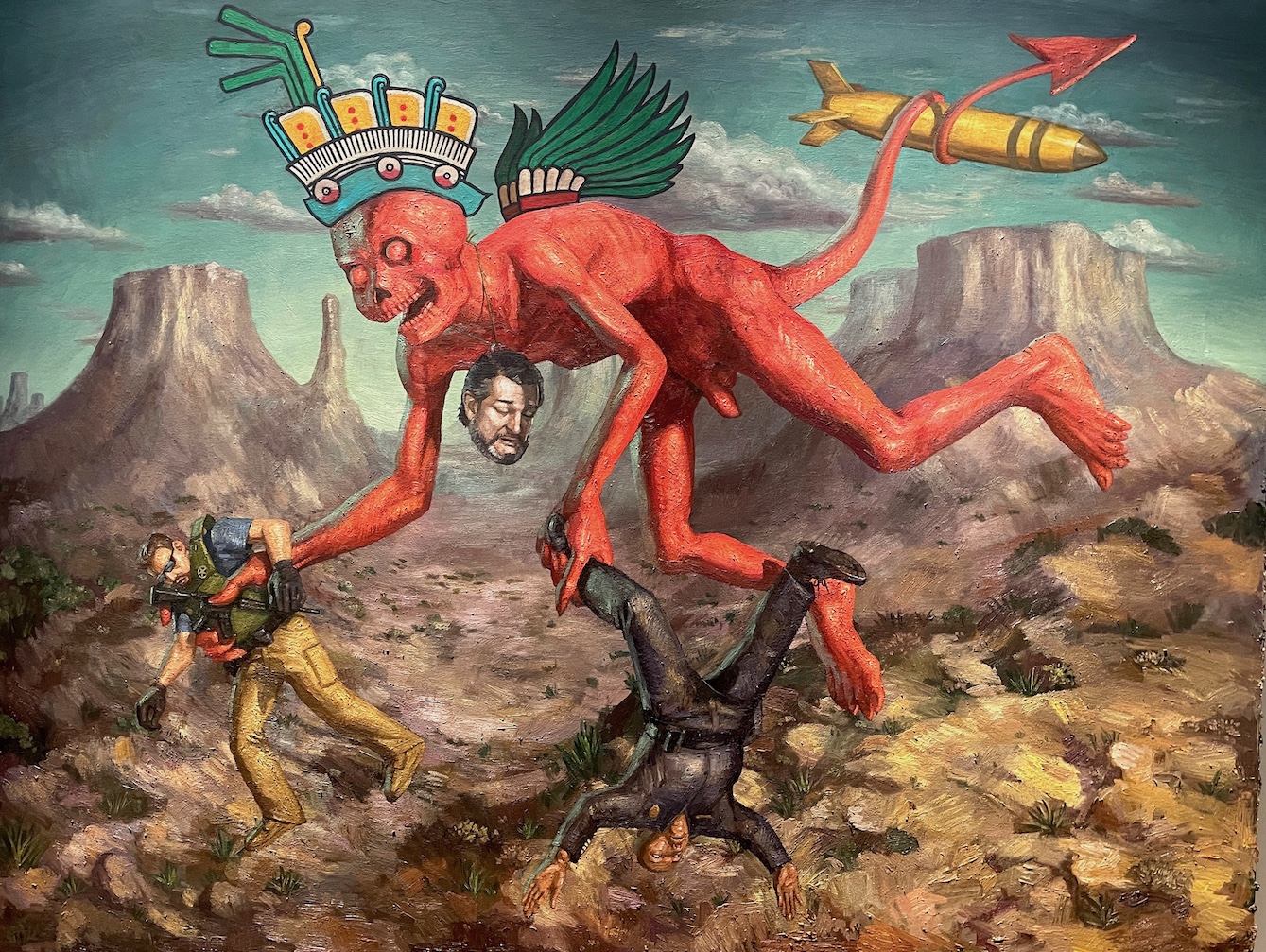

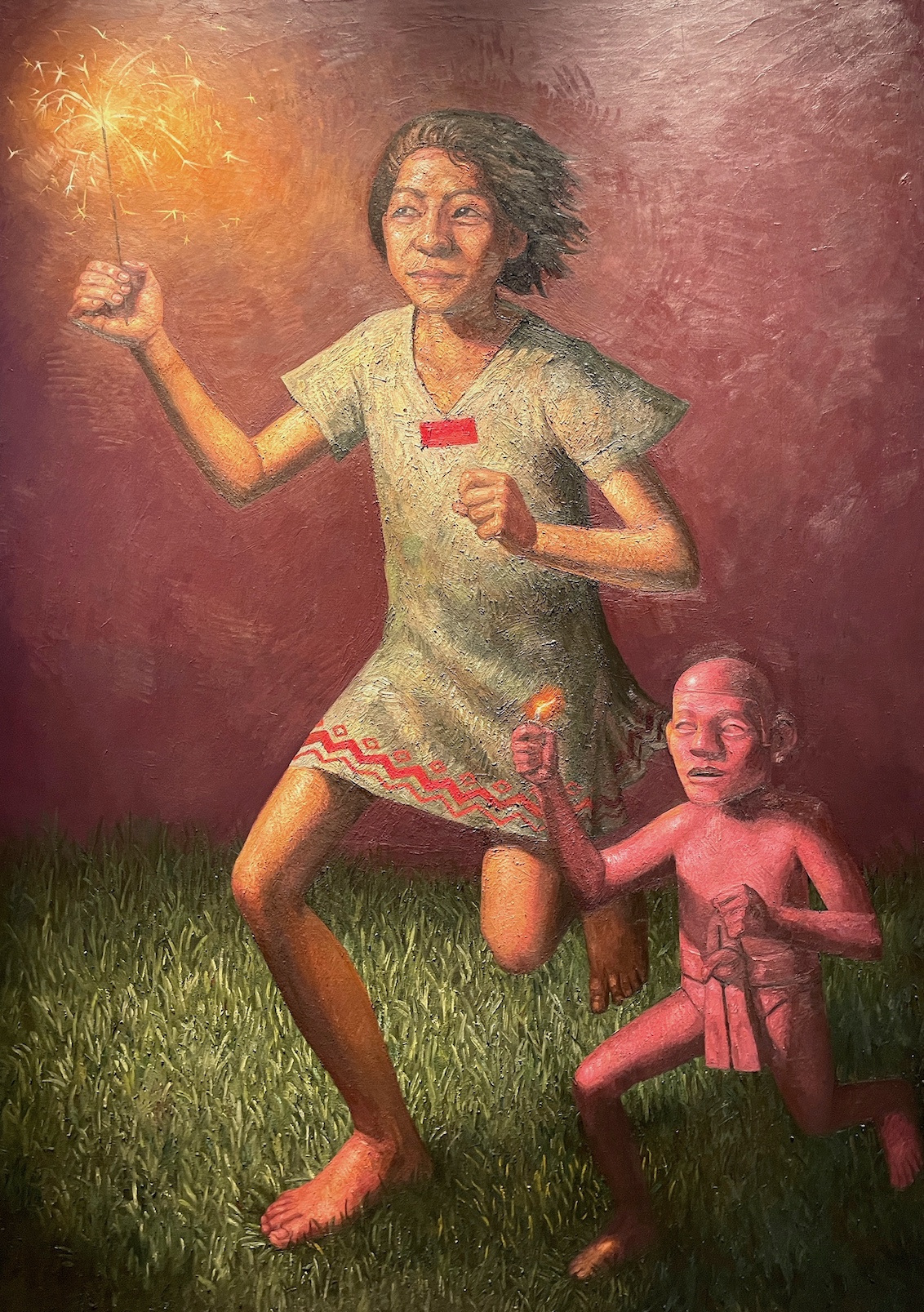

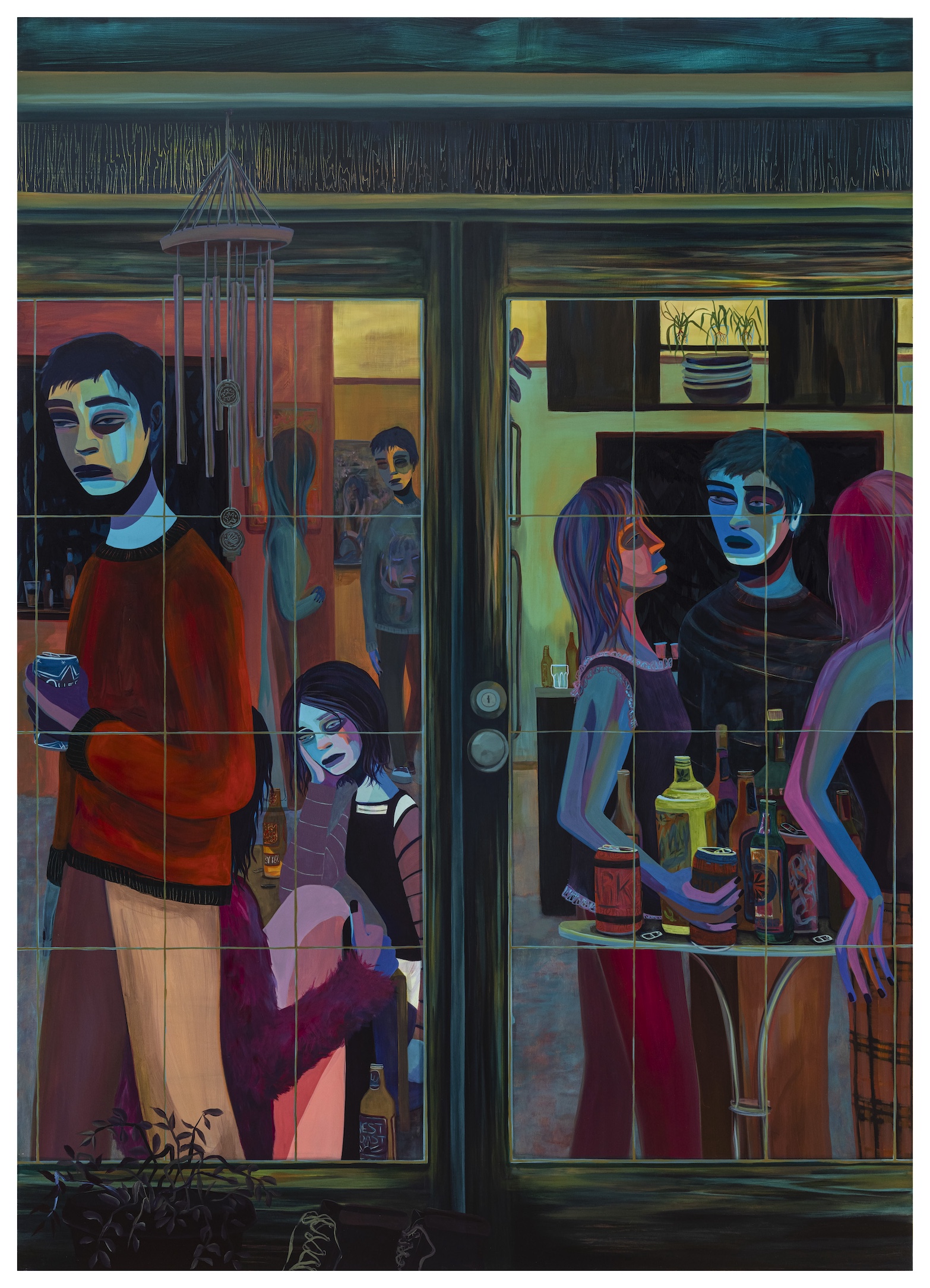

On entering BBAC, you’ll find yourself descending several steps into Jackson Wrede’s Menagerie in the center’s airy and spacious DeSalle Gallery. The lighting design in the room is particularly dramatic, and singles out Wrede’s individual color-packed works in ways that make them pop off the walls. See if you can resist their pull – the betting is you can’t. Wrede, who lives in Grand Rapids and is a graduate of the Kendall School of Art and Design, has remarkable skills in the hyperrealist realm, but these are not soulless, technical exercises. The face of the young woman in Girl Wearing Fur, for example, conveys an almost palpable sense of emotional depth.

Jackson Wrede, Girl Wearing Fur, Oil on linen panel, 24 x 18 inches.

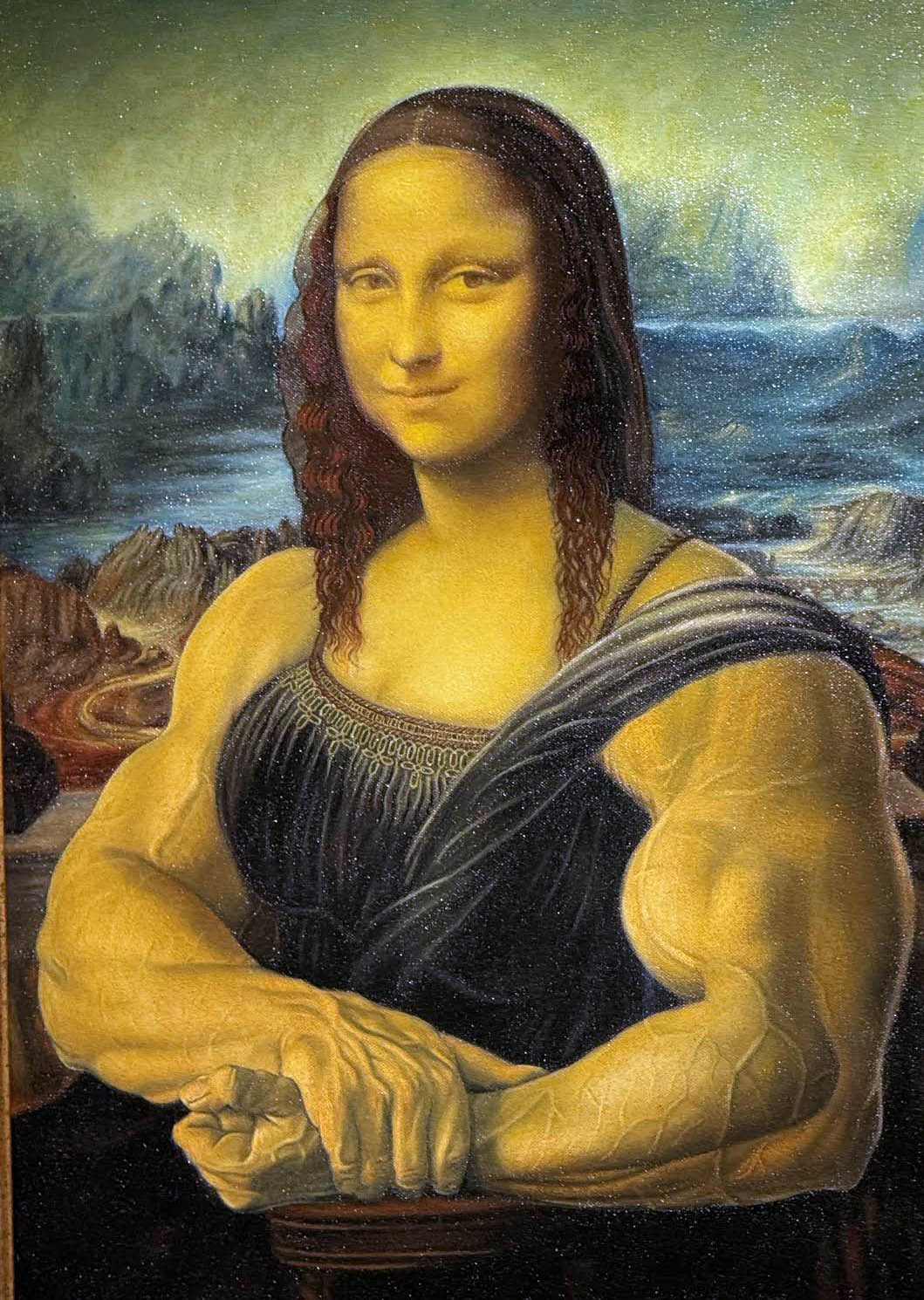

It has to be said that Wrede’s oeuvre is both wide and impressively ecumenical, ranging from the sensitive portrayal above to an equally compelling picture of electric-green iguanas sharing a very private moment. Or consider Wrede’s take on the Mona Lisa, sporting a pair of hyper-developed, Arnold Schwarzenegger arms. Truth be told, in Mona Lifta (note the distinction), she looks even more pleased with herself than usual. But credit Wrede with precision: Everything above the icon’s shoulders is exactly as it is in Da Vinci’s original, even down to the pastoral landscape behind the subject that appears to be happening at two dramatically different levels. Overall, the portrait is great fun, shot through with absurdity and humor. Bring the kids. They’ll love it.

Jackson Wrede, Mona Lifta, Oil on canvas, 20 x 14 inches.

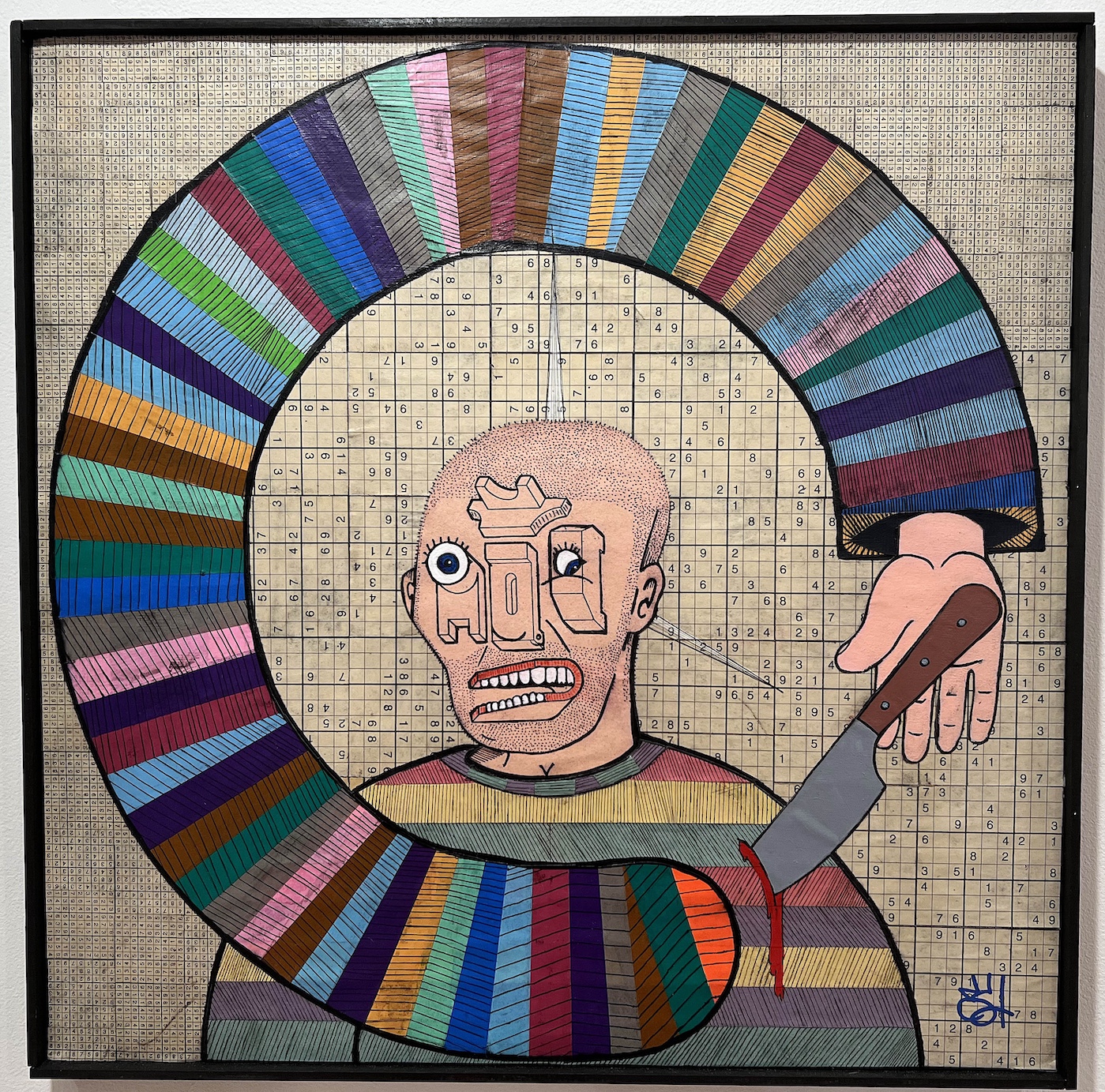

In a 2023 interview with the online British magazine, “Behind the Artist,” Wrede said that despite the classical formality of many of his pieces, he pretty much goes on gut instinct.

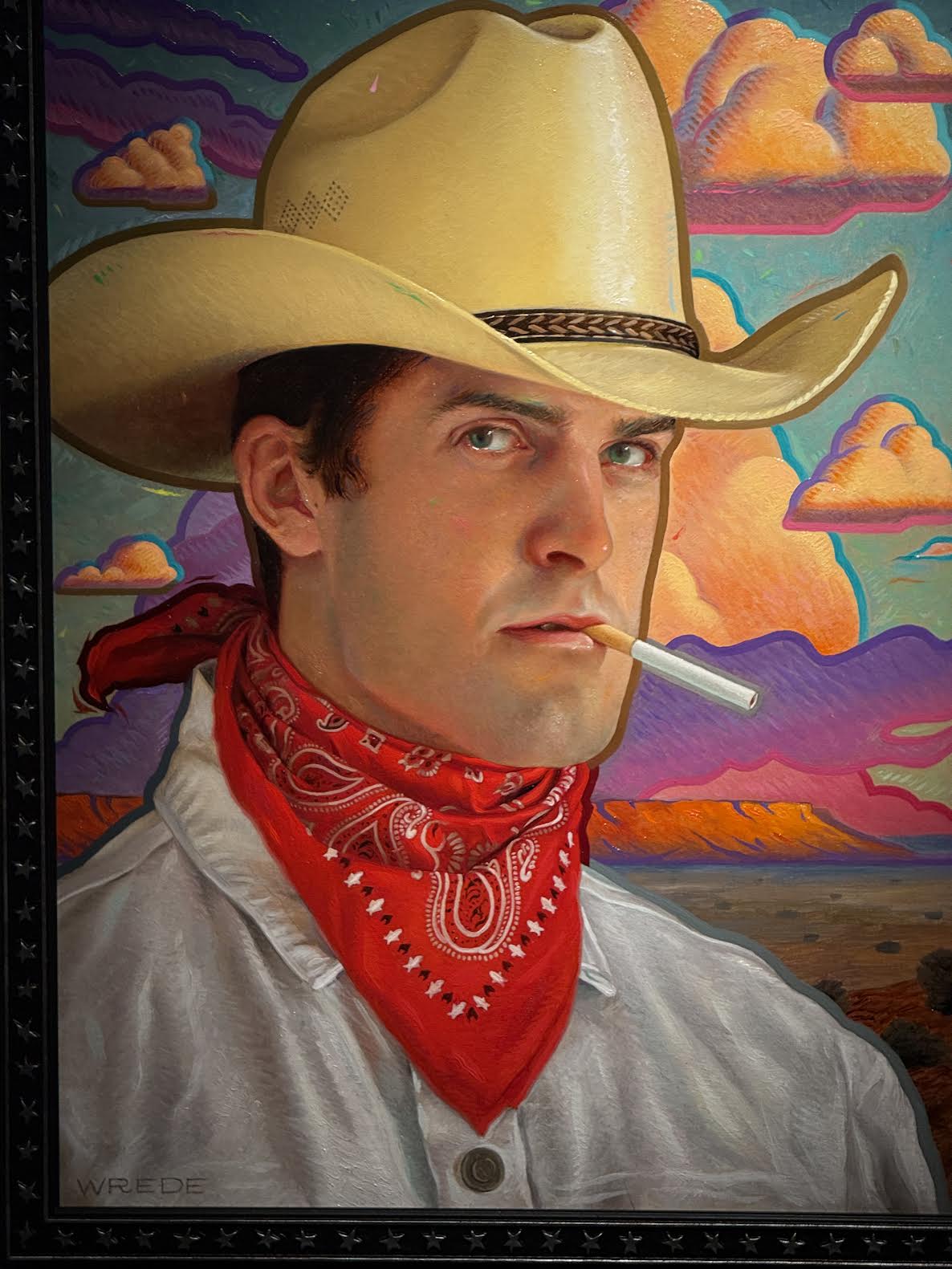

“So many artists have rules or templates they think about when composing an image—the rule of thirds, the Golden Ratio, we’ve heard them all,” he said. “I don’t use any of those really. Perhaps they accidentally come out in my work sometimes, but I think the main question you have to ask yourself is, ‘Does this look cool?’” And certainly, in the case of the self-portrait below, with its cartoon aesthetic, the answer pretty much has to be “Yes.”

Jackson Wrede, Self-Portrait in a Cowboy Hat, Oil on linen panel, 24 x 18 inches.

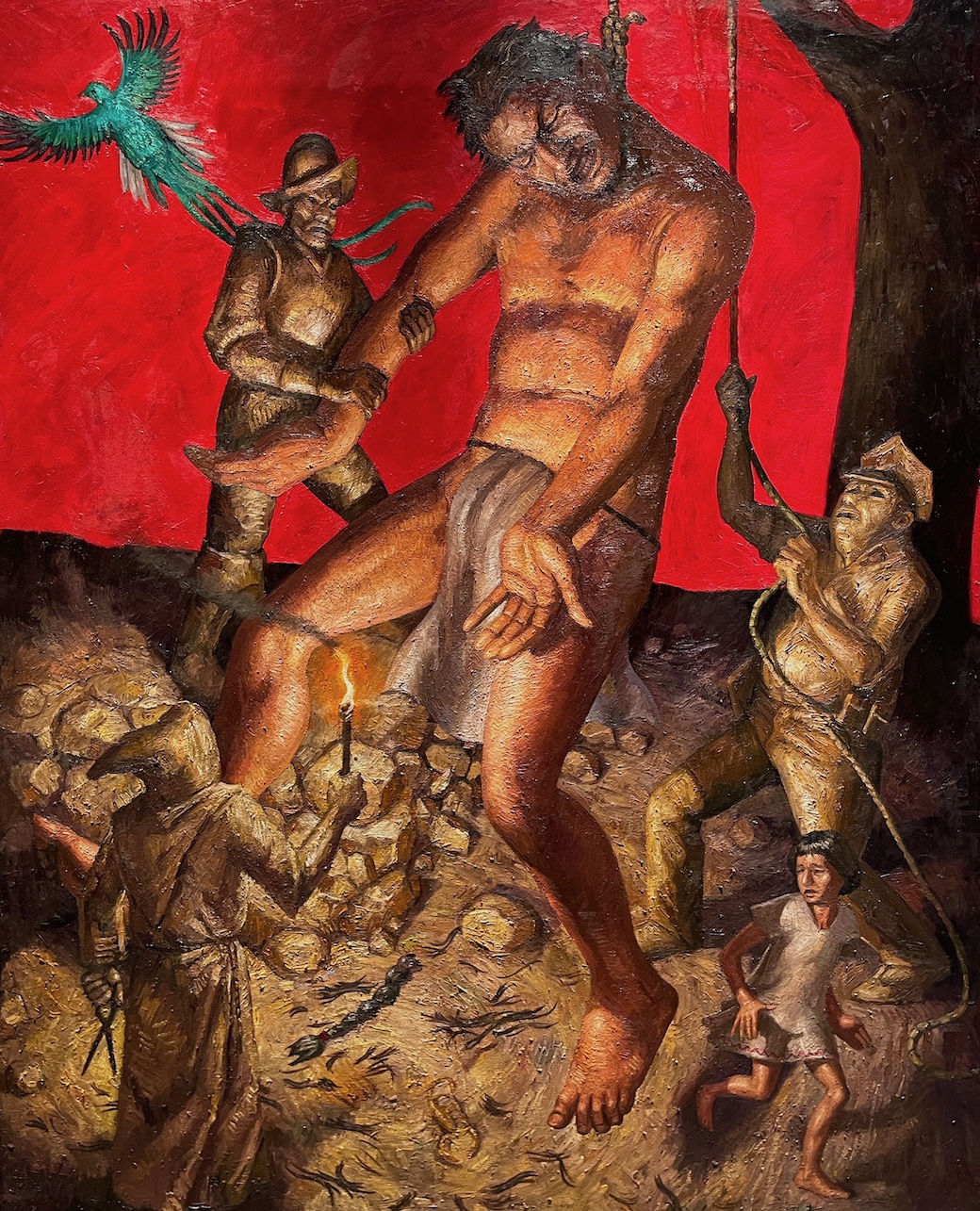

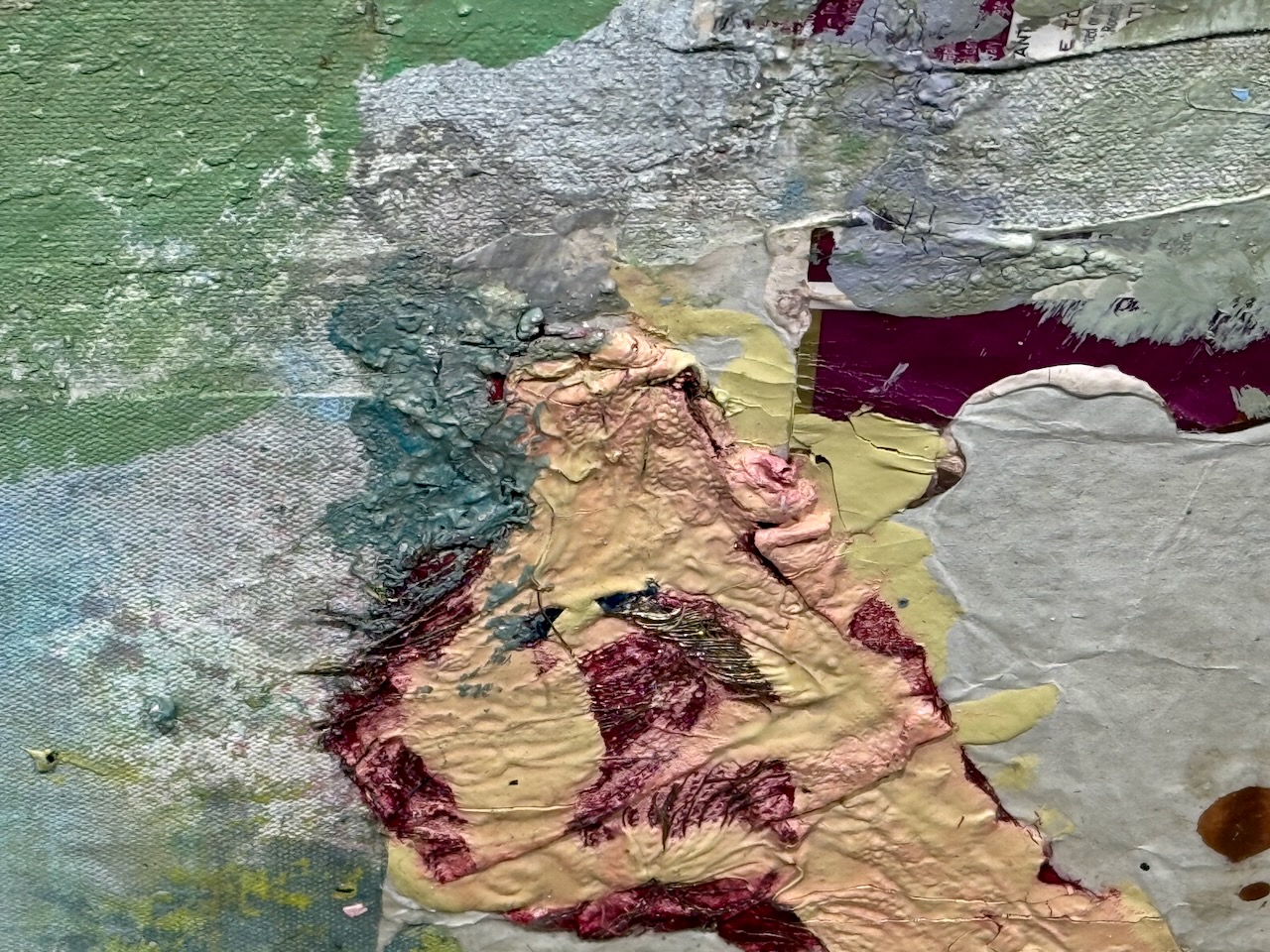

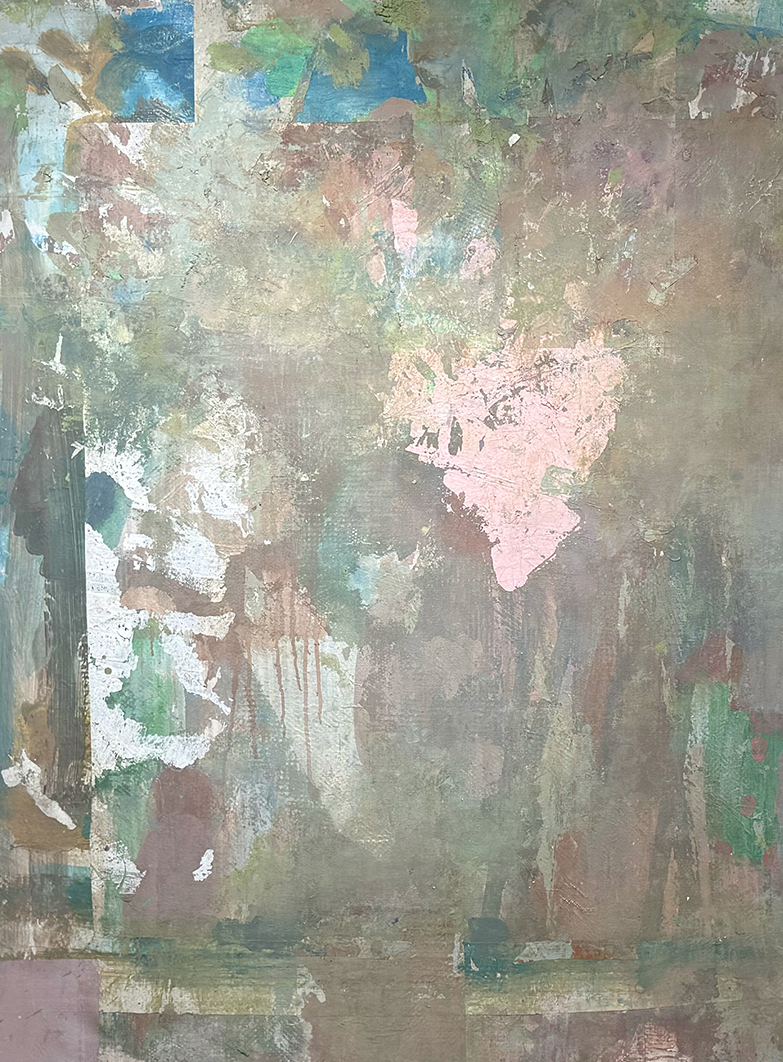

Detroiter James Kaye plows a completely different furrow than Wrede. Most of Descriptive Intuition in BBAC’s Robinson Gallery falls into the abstract-expressionist basket, and these works are rendered with a certain, for lack of a better word, forcefulness. They certainly command attention. And the level of technical skill and detail the College for Creative Studies grad deploys is daunting. Consider Dissecting Escape, somewhat more monochromatic than many of the works on display here, with its dozen-odd horizontal canvas strips sewn together and then painted in highly textured relief. The acrylic and enamel are applied in seemingly slapdash fashion, built up in layers and punctuated by small dots of strong red. The upshot is the piece reads as both free form and, with all those parallel stitched lines, oddly structural at the same time. It’s a gratifying juxtaposition.

James Kaye, Dissecting Escape (detail), Canvas, foam, acrylic paint, enamel paint, steel.

Kaye, a College for Creative Studies graduate, has snagged one long wall for his Fingertips 1-24 series, a parade of two dozen identically sized abstracts clearly painted with gusto and starring strong splotches of color. The individual works are charming, but it’s the visual power of all 24, marching across the wall two by two, that makes it such a magnetic sight.

James Kaye, Fingertips 1-24, Enamel paint, glue, acrylic paint.

Kaye doesn’t confine himself just to painting. He’s also got a small collection of sculptures and vessels on display, which have every bit as much authority as the canvases. Intriguingly, his bowls are all crafted from turned wood, despite looking for all the world like they were highly glazed works created on a potter’s wheel. Consider Flying, a warm, maple vessel that features a wood-grained base partly painted over in strong gray, black and white circles. The aesthetics of the sharply outlined dots stand in contradiction to the veined wood, yet the combination of the two is both peculiar and pleasing – about the best any artist could hope for.

James Kaye, Flying, Spalted maple, enamel paint, epoxy.

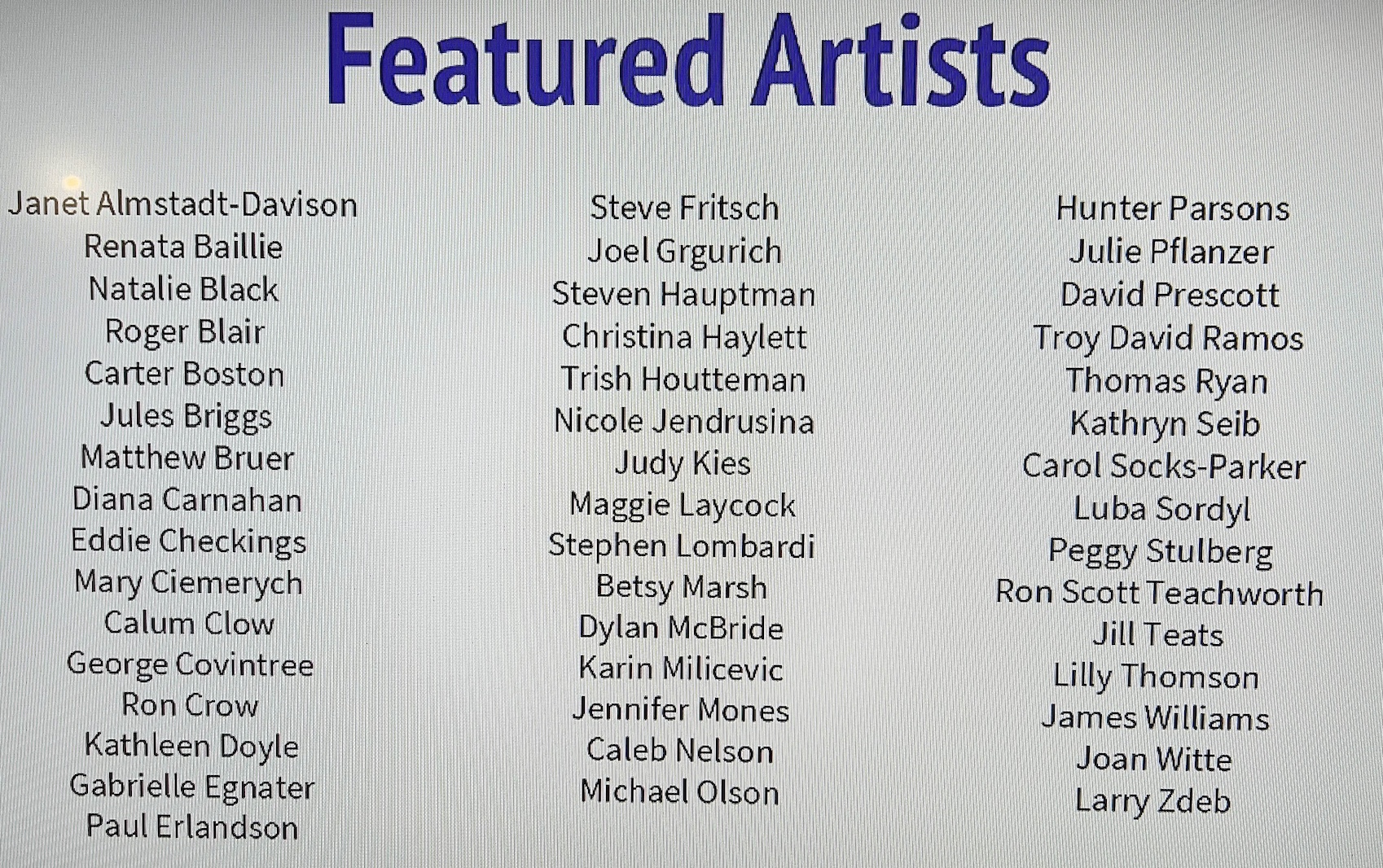

Two exhibitions will be at the Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center through May 1, 2025: Jackson Wrede’s Menagerie and James Kaye’s Descriptive Intuition.