Today, Frank Stella’s paintings (better described as sculptures, really) burst from the wall, exploding forcefully into our space. But it was Stella’s flat and austere Black Paintings created while he was still a student at Princeton that originally thrust him into the national spotlight. Through April 23, a modest but important ensemble of three lithographs recently gifted to the University of Michigan Museum of Art (UMMA) reminds us that before his paintings brazenly shattered the fourth wall, Stella was first and foremost the master of emphatically two-dimensional canvasses thoroughly unburdened by any adherence to illusionistic space.

Frank Stella (American, born 1936), Lac Laronge IV, 1969, Acrylic on unprimed canvas. Toledo Museum of Art, Purchased with funds from the Libbey Endowment, Gift of Edward Drummond Libbey. ©Frank Stella. 1972.4

Stella’s meteoric rise began when, as a graduate fresh out of Princeton, his work was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art’s Sixteen Americans exhibition in 1959. During the 1960s, Stella’s work adhered to the flat aesthetic of his Black Paintings, though he began experimenting with radically unconventional canvas shapes. Among these were his whimsical Notched-N paintings, canvasses which defied the centuries-old conception of painting as illusionistic and necessarily bound to the confines of a rectilinear surface. His stacked chevrons of muted color bands are never confined by any frame, blurring the boundary between painting and sculpture. In 1967, Stella began a famous collaboration with printmaker Kenneth Tyler, founder of the (then) Los Angeles based Gemini Studio, and Stella began to transpose his paintings into lithography.

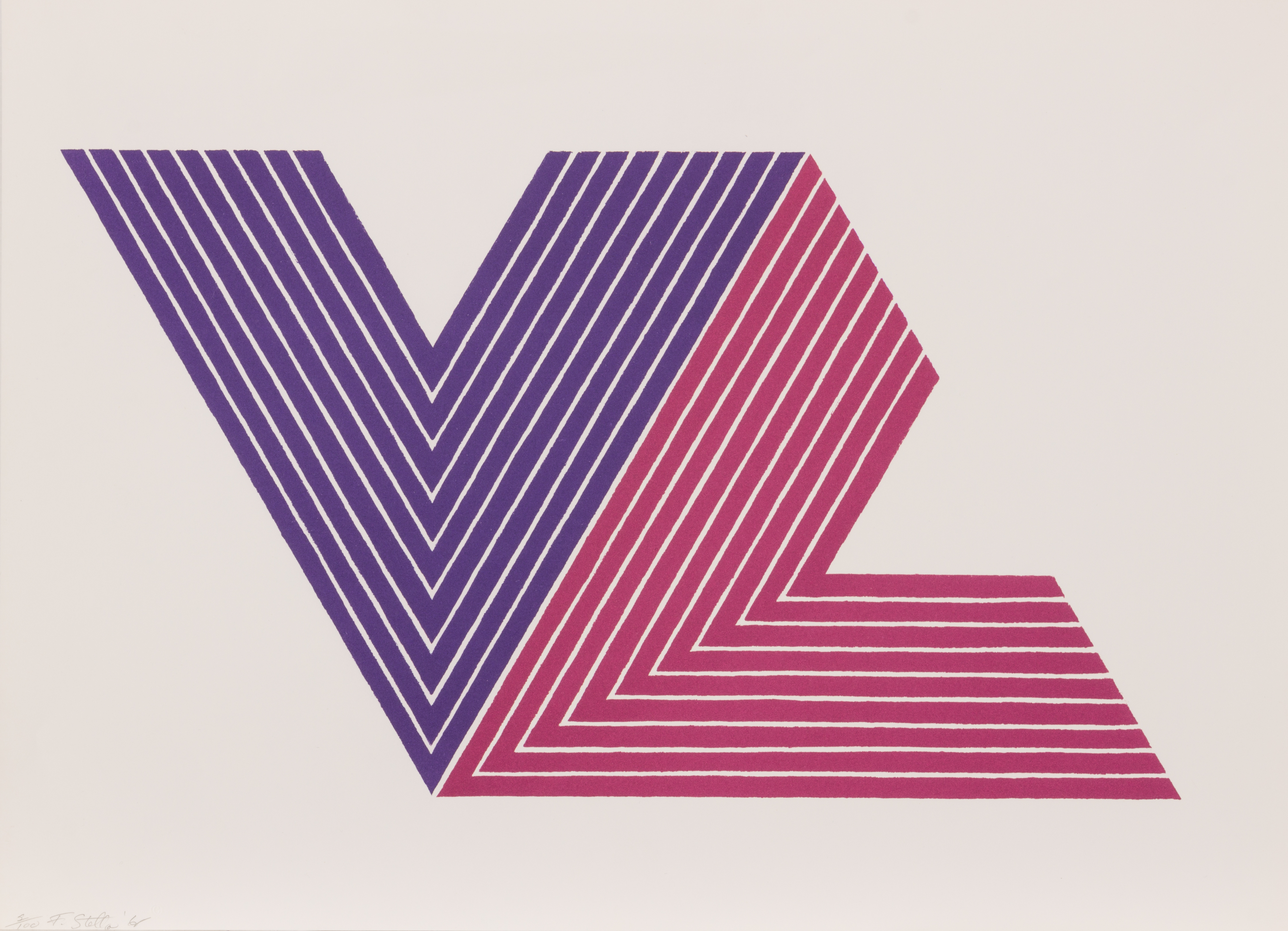

Frank Stella, Empress of India II, from Notched-V series, 1968, lithograph on paper. Gift of Marsha L. Vinson and Marvin Rotman, 2014/2.19

It was one of many collaborations for Tyler, who also worked with 20th century art-world heavyweights such as Robert Motherwell, Josef Albers, Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, and David Hockney. With Stella, Tyler produced a series of lithographs based on Stella’s Notched- Ns. Look for Empress of India II; it’s a diminutive print based on the majestic, sprawling, 18-foot Empress of India in the permanent collection of the MoMA. The three lithographs on view in the UMMA’s Corridor Gallery were produced in the first year of their lifelong collaboration (they worked together until Kenneth Tyler closed his studio in 2000).

Frank Stella, Ifala I, from Notched-V series, 1968, lithograph on paper. Gift of Marsha L. Vinson and Marvin Rotman, 2014/2.20

Initially, it’s difficult to be impressed by them, perhaps simply because as 21st century viewers, we might reflexively associate their crisp, geometric lines with computer-generated art—merely the photoshoped creations of easy copy-and-paste. But if we lean in close, we’ll see the subtle imperfections that betray the human touch. (Significantly, even Stella’s large geometric abstractions of the same era reveal marks of the human touch; lost in translation when reproduced in textbooks, in person we can see the subtle pencil lines that demark the separation between color borders.) The lithographs are also tactile; the ink rising from the page gently but unmistakably pushes out into our space; one lithograph even shows gentle signs of distress; an effect which doesn’t translate in digital reproduction.

Frank Stella, Quathlamba II, from Notched-V series 1968, lithograph on paper. Gift of Marsha L. Vinson and Marvin Rotman, 2014/2.21

Long after he had moved beyond his minimalism, Stella maintained his partnership with Tyler. Among the more famous (and audacious) of their later collaborative works was Stella’s series of loosely illustrative prints based on Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. These intensely sculptural prints press out into viewer space, and– technically virtuosic– took years to produce.

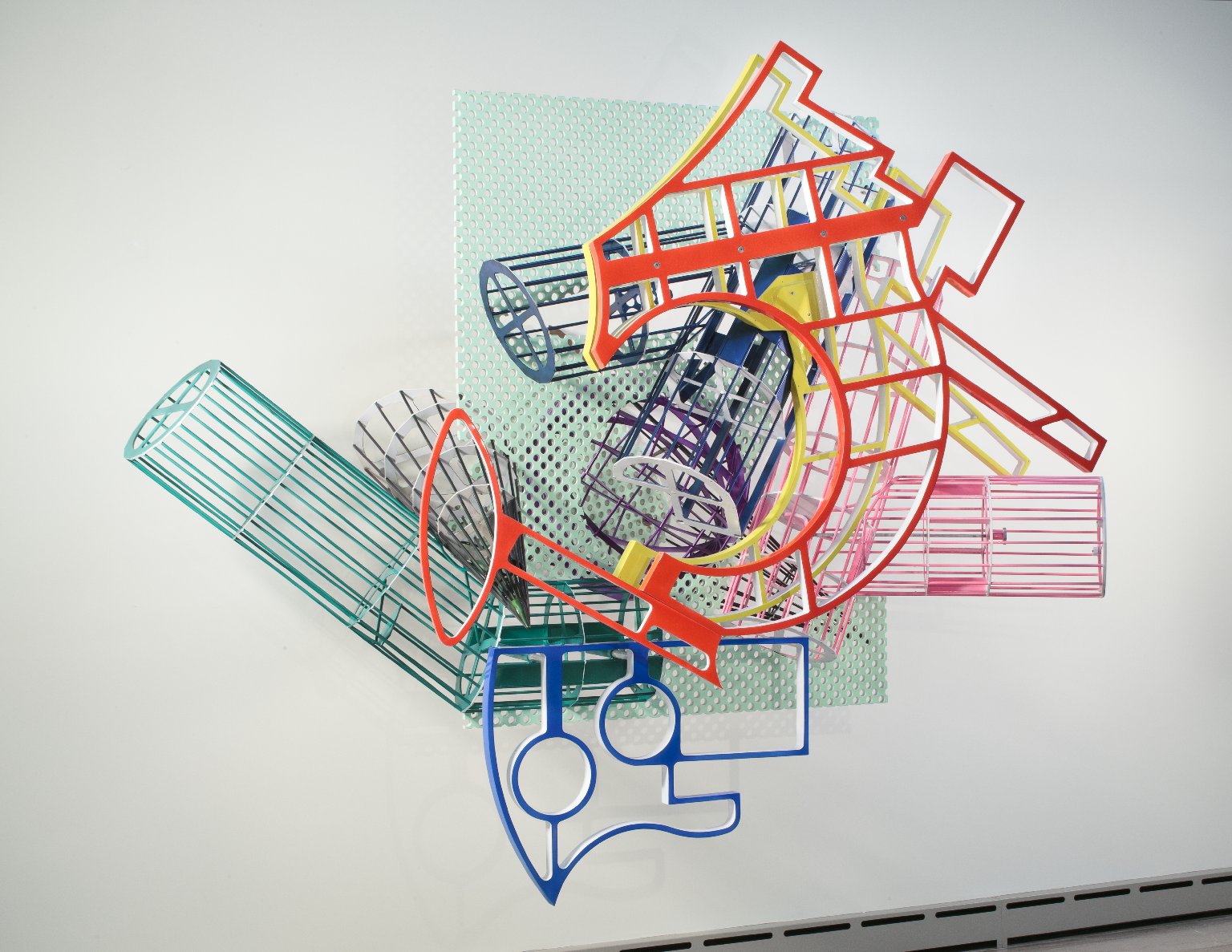

Frank Stella (American, born 1936), La penna di hu, 1987-2009, Mixed media on etched magnesium, aluminum and fiberglass. Toledo Museum of Art. Museum purchase, by exchange. ©Frank Stella. 2014.104

Today, Stella’s works are, at least on first appearance, the complete antithesis of his minimalist abstractions of the 1960s. Take, for example, his playfully obnoxious La penna di hu (1987-2009), a recent work currently on view at the Toledo Art Museum. It’s sculptural in every sense, perhaps its only initial commonality with his paintings of the past being that it hangs on a wall. Yet, like Stella’s Notched-Ns, it nevertheless fights the notion that art should be illusory, and, in this respect, Stella’s oeuvre has remained strikingly consistent.

In comparison with his playfully sculptural three-dimensional collages, the works from Stella’s formative years as a minimalist artist perhaps seem weighted down by an austere solemnity, their meticulously calculated arrangements of shape and color eluding interpretation. But these serene, meditative works brazenly defied the notion of art as the conduit of illusion and narrative, and the three lithographs on view at the UMMA stand as historically important documentation of Stella’s celebrated early days as 1960s minimalist, emphatically the art world’s undisputed modernist master of Flatland.

Frank Stella, Lithographs, UMMA – April 23, 2017