Exercising the Eye

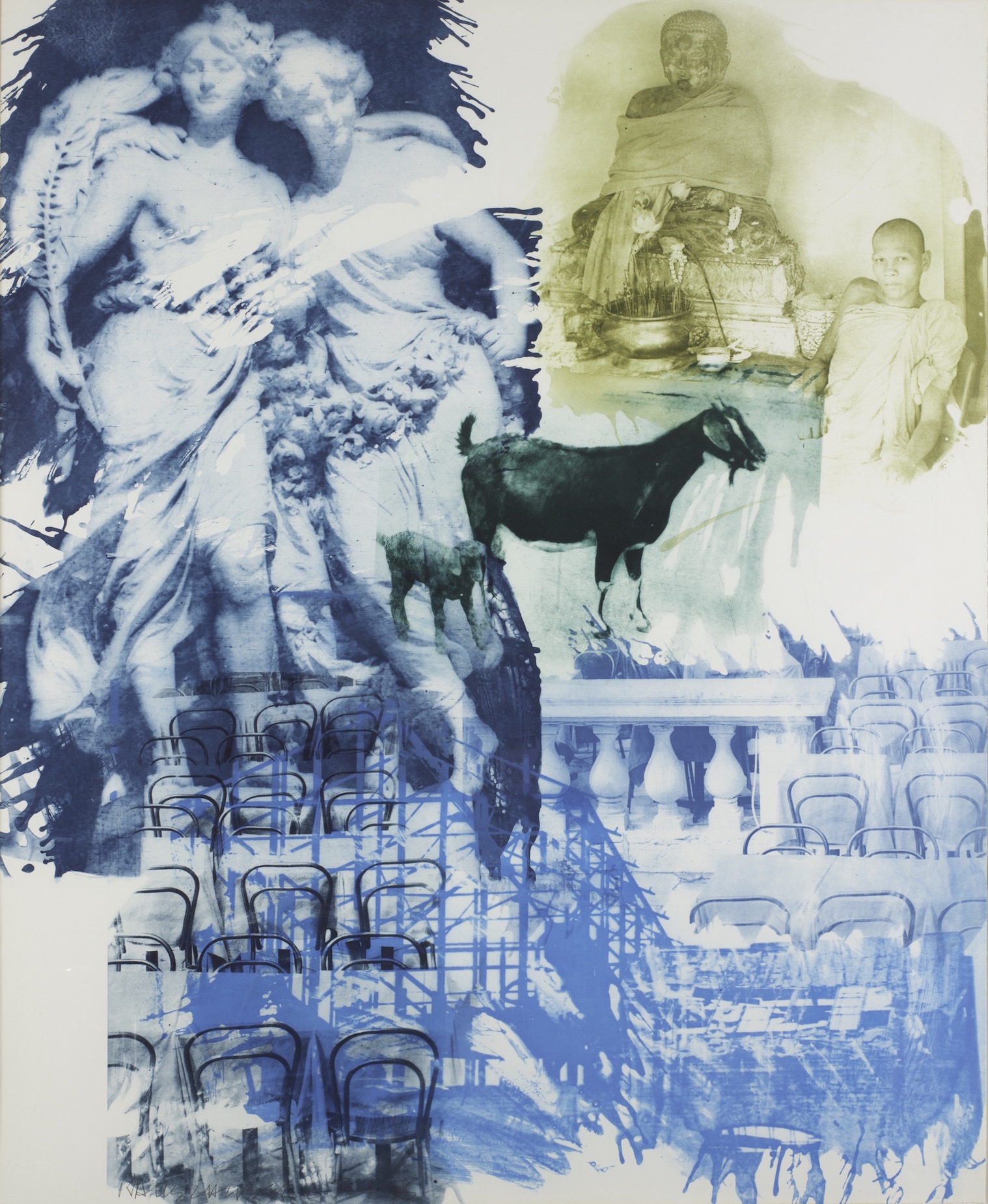

Robert Rausehnberg, Intermission(Ground Rules) Intaglio, 1996

In 1965, Gertrude Kasle established a gallery in Detroit’s Fischer Building with the intent of introducing the New York School of abstract expressionism to the Midwest. The gallery lasted for 11 years, during which she acquired and exhibited works by luminaries such as Willem de Kooning, Robert Rauschenberg, and Grace Hartigan. An alumnus of the University of Michigan, Kastle subsequently donated her muscular collection of American postwar art to the university’s art museum, and through July 22, Exercising the Eye celebrates Kasle’s visionary, connoisseurial eye.

Jasper Johns, Savarin, Color Lithograph on Paper, 1977

Exercising the Eye comfortably fills the UMMA’s large Taubman Gallery with a veritable Who’s Who of American Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art of the 60s and 70s, alongside a generous selection of works by artists perhaps underrepresented in the typical art-history survey. An impressive spread of Rauschenberg’s works fills an entire wall, including diminutive aquatints and lithographs, a reminder that Rauschenberg produced far more than the “combines” for which he became famous. Nearly running the length of another wall is a suite of immersive, large paintings by Grace Hartigan, a staple among America’s abstract expressionists and friend of Jackson Pollock, Helen Frankenthaler, and the de Koonings. Hartigan worked both in abstract and figurative imagery, challenging Clement Greenberg’s vocal and uncompromising championing of pure abstraction, and here her immersive Tarzana applies frothy scribbles and uninhibited swaths of smack-you-in-the-face color to deliver the fleshy exuberance of a Renaissance Bacchanal translated into the vocabulary of postwar expressionism.

Other artists represented include Robert Motherwell, Adolph Gottlieb, Jasper Johns, and Philip Guston (the later represented with an original pen drawing advertising a show if his own paintings at the Gertrude Kasle Gallery). Exercising the Eye perhaps suffers mildly from a lack of thematic continuity beyond its works having been collected and exhibited by Gertrude Kasle, shrewdly perceptive as she may have been. But its strength rests on the admirable willingness of Kasle to acquire and exhibit works by worthy artists that had yet to attain household-name status, and this exhibition is a markedly inclusive reflection of the climate of postwar American art, which often seems mischaracterized almost as a sort of boys-only club.

The Treachery of Images

Elliott Erwitt, Cracked Glass with Boy – Colorado, Gelatin Silver Print, 1955

Concurrent with Exercising the Eye, the UMMA is also presenting a show of pictures in its photography gallery which collectively aim to “expose the contingent nature of reality” through a series of visually beguiling photographs, each guaranteed to procure a double-take from the viewer. The exhibition, See Through: Windows and Mirrors in Twentieth-Century Photography, brings together an eclectic selection of images that visually pun on the nature of the image and in which nothing is quite as it seems. It’s as if the visual devilry of Rene Magritte has been transposed into photography, and, impressively, all of it prior to the advent of photoshop.

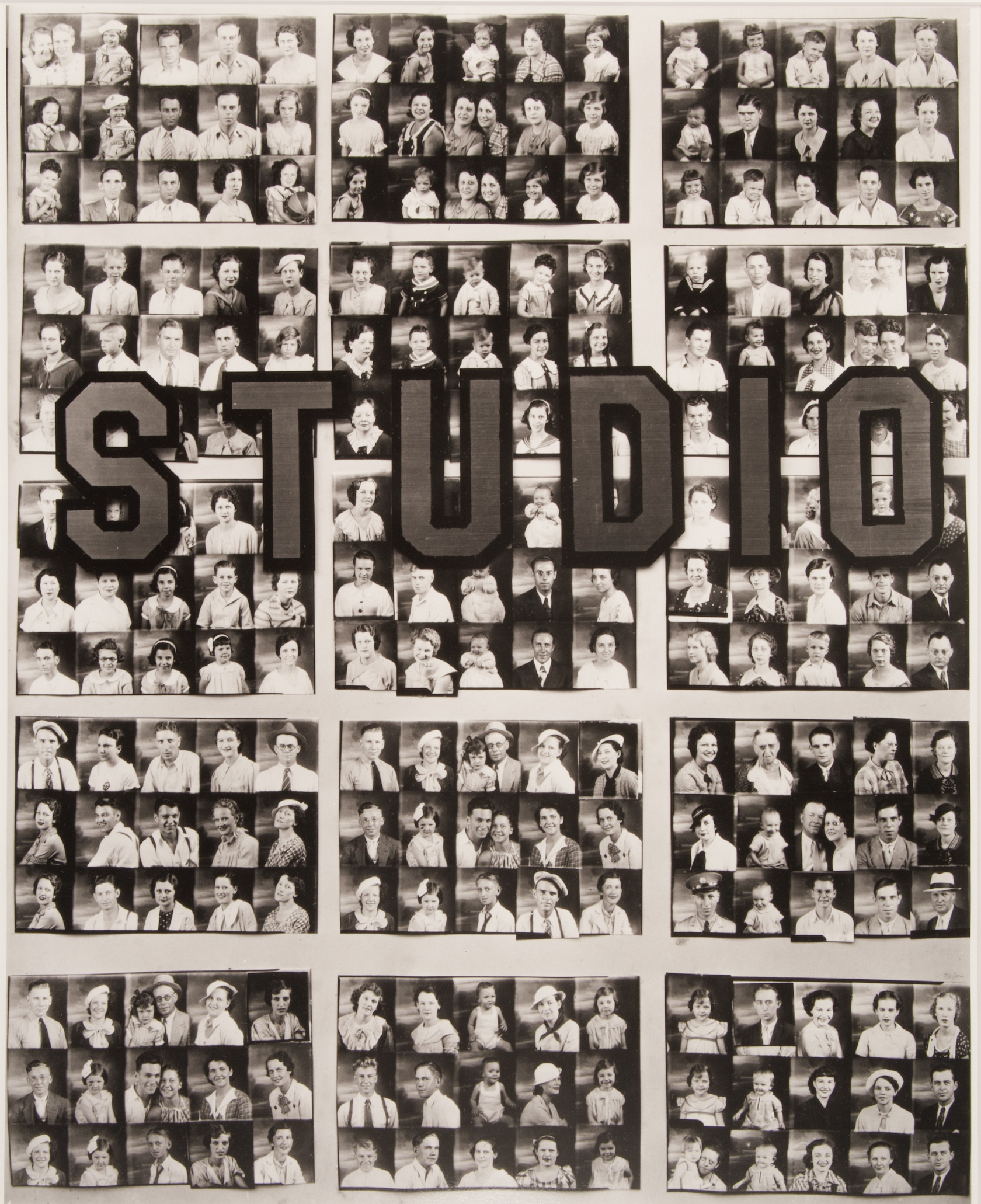

Walker Evans, Penny Picture Display, Savannah, Gelatin Silver Print, 1936

Walker Evans, generally known for his soul-wrenching portraits of down-and-out Depression-era families of the American South, is here represented with an uncharacteristically lighthearted set of illusory images that seem to portray special depth where there is none. A wry photograph of a mirror in a hotel lobby, for example, seems to open up a portal in the picture plain that leads to another room; of course, there’s nothing in front of the camera but wall and glass.

Several images make playful use of distortion caused broken glass. Carl Chiarenza’s Bat Windowpresents a smashed window, its break forming an ominous angular black hole resembling the shape an abstract bat; the encroaching field of black recalls the schematic of a Robert Motherwell painting. And Algimantas Kezys’ fragmentated reflection of two silhouetted male forms staring into a shattered mirror seems cubist, like a much paired down version of Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

Such a theme as this naturally opens the door to moments of subtle humor. Robert Doisneau’s wonderfully mischievous La Dame Indignée (“the indignant woman”) captures the moment a Parisian woman passes by a storefront window displaying a lascivious and revealing picture of a nude woman and gives the work a fiercely disapproving scowl. The picture was part of a series for which Doisneau stealthily photographed the varying reactions of passers-by, with this indignant woman on one end of the spectrum, and a visibly enamored man craning in for a closer look, on the other.

See Through is a small exhibition, fitting in its entirety on two perpendicular walls on the UMMA’s third-floor atrium. Nevertheless, While the primary draw of the show is visual, there’s a cultural resonance to these photographs which whimsically distort reality. After all, the alarming spread of pseudo-news on social media has demonstrated that a provocative image divorced from context can easily pass itself off as truth, and this exhibition serves as a gentle reminder not to instinctively take images at face value.

University of Michigan Art Museum

Exercising the Eye:The Gertrude Tase Collection, through July 22, 2018

See Through: Windows and Mirrors in Twentieth-Century Photography, through September 23, 2018