Gallery Installation and Andrew Krieger photos by R.H. Hensleigh – All others courtesy of Klein Gallery

It was an ironic surprise to discover an exhibition with such seemingly disconnected and ho-hum interests—and so painfully arty—that, at the same time, ran so deep and held up to sustained investigation. While Alisa Henriquez’s assemblages are spectacular “coats of wonder” in their amalgam of artistic gestures (cubist fragmentation, nouveau arabesques, abstract expressionistic slashes), and skillful making, yet their formal arrangement of stacked pill or capsule shapes seemed architecturally random and off-puttingly glitzy. And Andy Krieger’s cast ceramic and wood carved reliefs seemed over worked and Brad Howe’s immaculate metal sculptures seemed antiseptically inconsequential.

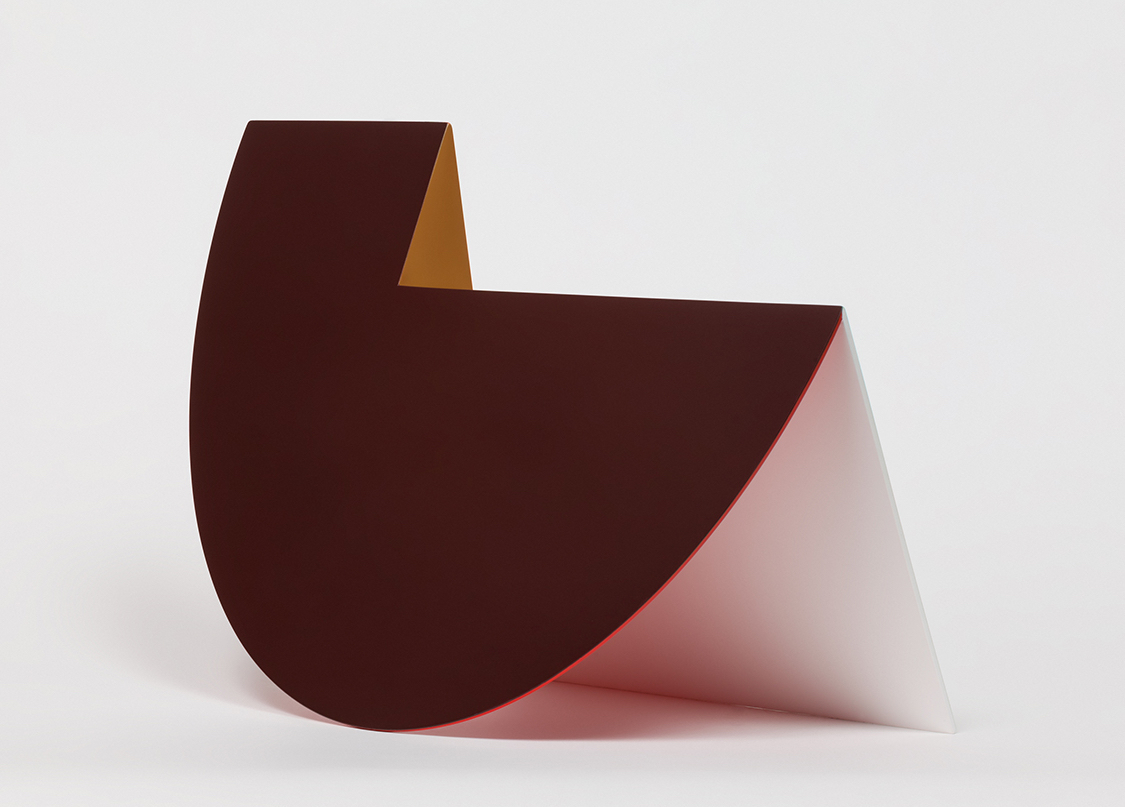

Brad Howe, 1 of 2 views of “The Planet is a Wild Place,”2018, Stainless steel, urethane, 13” x 19” x 7”

However, during a second visit, one of Brad Howe’s small, table-top sized sculptures emerged from the arty landscape. In the gallery window, a black semi-circle with rectangular sidebar leaned back and away, and appeared to float independently in the air. It was a visual mystery. It shouldn’t be able to do that without falling. Changing viewpoint slightly, the back side of the sculpture revealed itself slightly showing a supporting back element with a bright red edge and mocha brown triangle floating behind. Changing viewpoint even more, the black semi-circle disappeared and a red semi-circle appeared with a celadon green panel supporting it as well as the mocha brown triangle. Changing positions more and the whole sculpture flattened out into a red, black and green geometric abstraction, somewhat Ellsworth Kelley-like. Titled “The Planet is a Wild Place,” the sculpture is a tutorial in how to see with the unstated lesson to never jump to conclusions. What was nothing became something and challenging.

Brad Howe, 2 of 2 views of “The Planet is a Wild Place,”2018, Stainless steel, urethane, 13” x 19” x 7”

Each of Howe’s four small sculptures and the one large sculpture do similar work. Composed of either stainless steel or aluminum and coated in a brilliant, mixed pastel palette of flat urethane, the geometric volumes are complex puzzles, that tease perception and delight the senses. Simple geometric puzzles, Howe’s sculpture perform a complex task that challenge how and what we see.

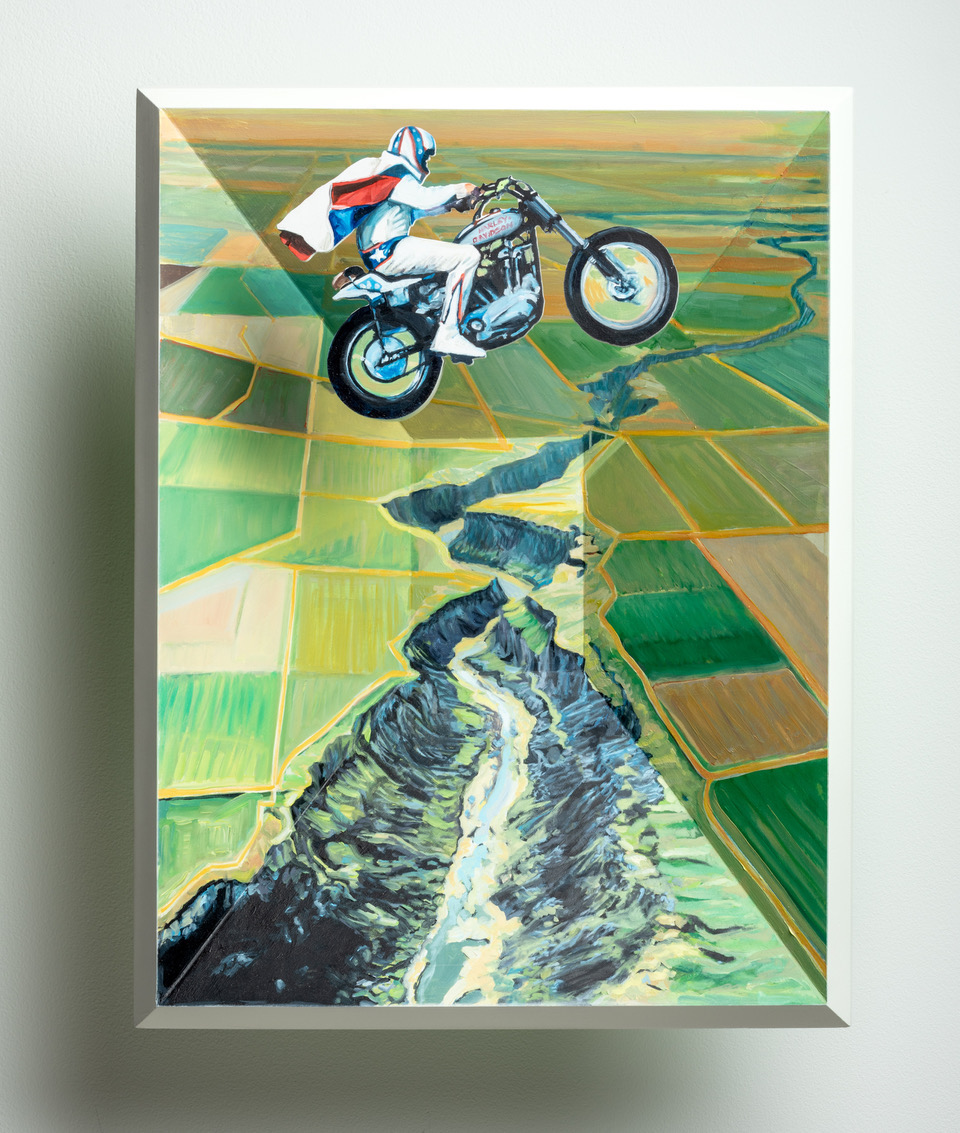

Andrew Krieger, “Writing Wrongs: The Snake River Canyon Jump, September 8, 1974,” 2019, oil on wood form, 23 1/2” x 18” x 9”

And similarly, Andy Krieger’s, beautifully constructed, folk-art-like reliefs and dioramas, constructed of either laminated plywood or molded stoneware, slowly unfold personal or historical moments. What seemed like “over worked” craft was part of the process of remembering or memorializing. Like unknown images found in a “collectibles” booth, Krieger’s nostalgically familiar, but really unknown images, celebrate the lost part of ourselves. Sometime they appear as faded color photos that places them historically, probably to Krieger’s own youth or even to the public memory, found somewhere. They suggest archetypal memories, even primal dreams (flying, views from the sky), fantasies that never happened or things that did happen that suggest even deeper levels of meaning.

His painting “Writing Wrongs: The Snake River Canyon Jump, September 8th, 1974,” is a momentous public memory of Evel Knievel’s famed effort to “jump” the quarter mile wide canyon on his “skycycle.” Krieger seems to have internalized the popular event and recast it. The image has been slightly altered (Writing Wrongs) to show Evel Knievel on a Harley Davison, rather than the rocket-like contraption he actually used, to fit Krieger’s own fantasy “memory” of the event. It is also a wonderful aerial view of the landscape that only could be seen from a high-flying plane. In another vicarious version of the Evel Knievel’s jump, “Plywood Bike Jump,” a boy flies over a makeshift slanted plywood jump to get airborne enough to ascend over two playmates lying on the ground, like the deep canyon, beneath him. Krieger’s images are dredged from the public pool of pop culture and recast as to fit memory. It’s what we do.

Andrew Krieger, “A Brief History of Transportation,” 2019, Pressed molded stoneware with sgrafitto, black lava glaze, oil paint, 16 1/2” x 21 ½” x 6 ½”

In the main gallery, there’s four of Krieger’s stoneware reliefs on platter-like forms, with etched images, (sgraffito Italian for scratched) a classical European ceramic process of drawing on pottery or even on building walls. Each is etched with an uncanny image that confounds easy reading. In two of them a horse gallops through a working-class neighborhood (a boy hood fantasy?). In another, four rather rough looking men standing at an intersection, stare down the camera (viewer). Each of these looms out as a fragment of memory combined with fantasy. The scratched drawing and painting is elegant, and the process suggests s kind of tinkering with memory and desire. The fourth piece, “A Brief History of Transportation,” is a magnificent image of the Detroit River seen from high above the Ambassador Bridge with a thousand-foot freighter traversing the river, a huge jet going by (Air Force One?) and the Renaissance Center and Belle Isle in the distance. Beside a kind of folk elegance, the sgrafitti process suggest a tramp art-like perspective on the world, positioning the artist in a nomadic kind of relationship with history.

Alisa Henrique, “Makeover Culture Disfigured No.3,” Mixed media on wood panel, 2016, 52” x 68”

One of the most remarkable features of Alisa Henriquez’s assemblages is their complete, all over, optical assault. Her sure handed cut and paste gathering of peekaboo glimpses of everything from parts of women from media advertising—eyelashes, hands, eyes (iris and pupil), flowing images of hair and actual hair, little girls faces, breast cleavage and nipples, eyebrows, lips, body crevices, elbows, feet, toes, navels, breasts, nostril openings— to glossed advertising styling–all arranged within capsule and erotic body shapes and seamlessly inlaid amidst an array of cosmetic colors and materials, mascara and rouges and sprays, licks, sparkles and hard edges of every pretty thing–amazes. Like everyday life in America’s all over blitz on curating the female surface, Henriquez’s critical assault on that industry is relentless. Images of her work don’t do them justice. Her hand cut inlays seem laser cut and her syrupy, glistening surfaces, frightening. Interestingly there is only one male eye and a male hand (with a wedding ring), that I can find, gazing out at the empty landscape.

Alisa Henriquez, “Makeover Culture Disfigured No. 4,” 2016, Mixed media on wood panel, 39” x 19 ¾”

Fractured Beauty: Andrew Krieger, Alisa Henriquez, Brad Howe, David Klein Gallery, Through March 23, 2019