Sons: Seeing the Modern African American Male & Drawing from Life – Exhibition at the Flint Institute of Arts

Courtesy of the Flint Institute of Art and Jerry Taliaferro

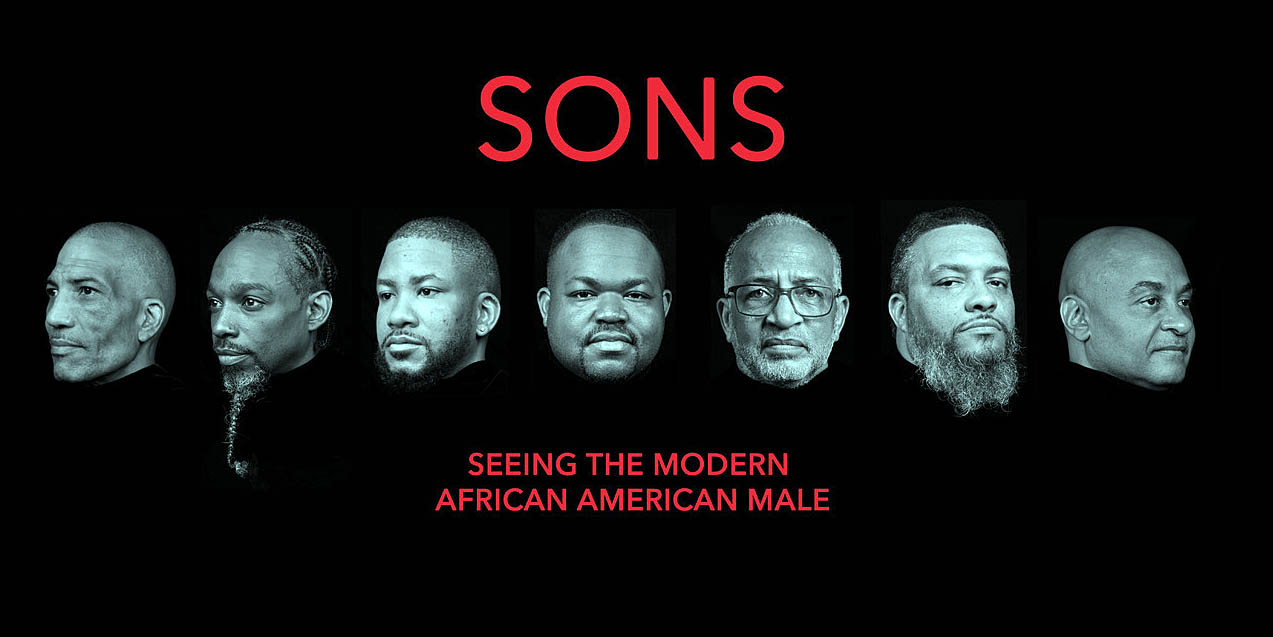

Five years ago, the Flint Institute of Art presented the exhibition Women of a New Tribe, an immensely popular photography show which celebrated the physical and spiritual beauty of 49 Flint area African American women, all photographed by North Carolina-based artist Jerry Taliaferro. An accomplished artist and commercial photographer, Taliaferro’s work has been exhibited in shows on both sides of the Atlantic, including two exhibitions sponsored by the U.S. Department of State. Taliaferro now returns to the FIA with Sons: Seeing the Modern African American Male. This is a large body of work that fills the FIA’s spacious Henry and Hodge Galleries, and serves to confront perceptions and biases while celebrating some of Flint’s civic, business, and spiritual leaders.

Courtesy of the Flint Institute of Art and Jerry Taliaferro

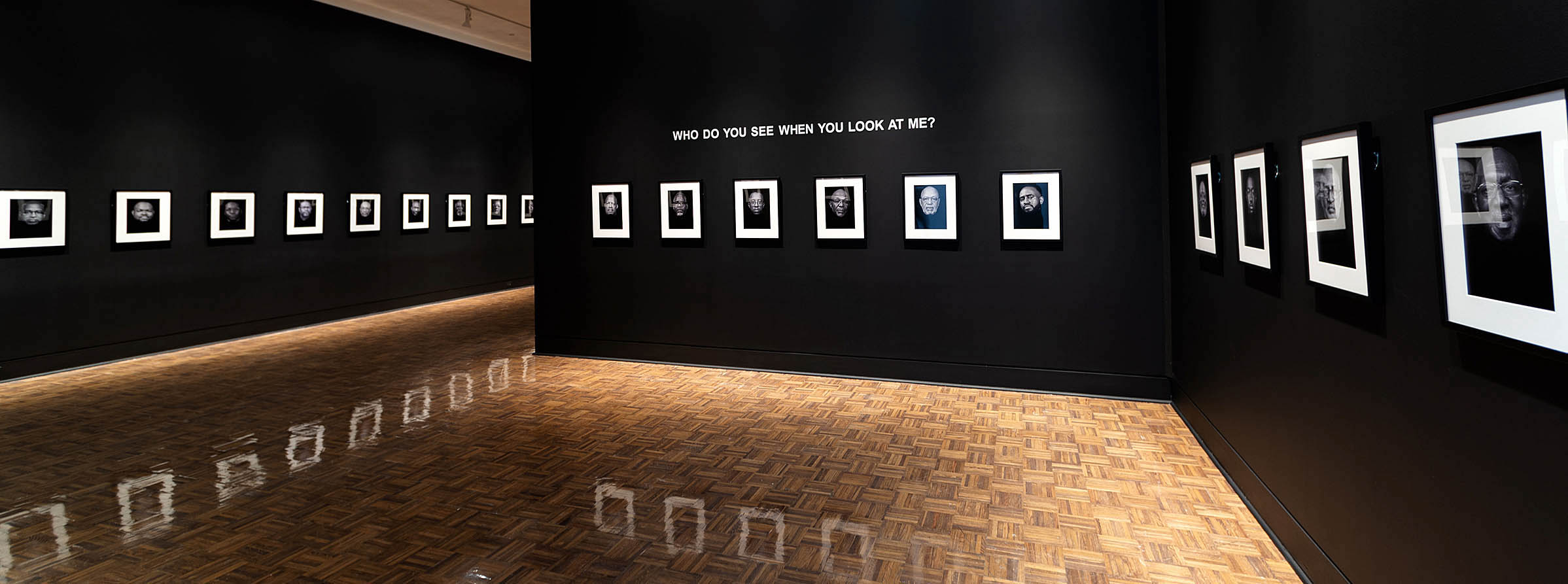

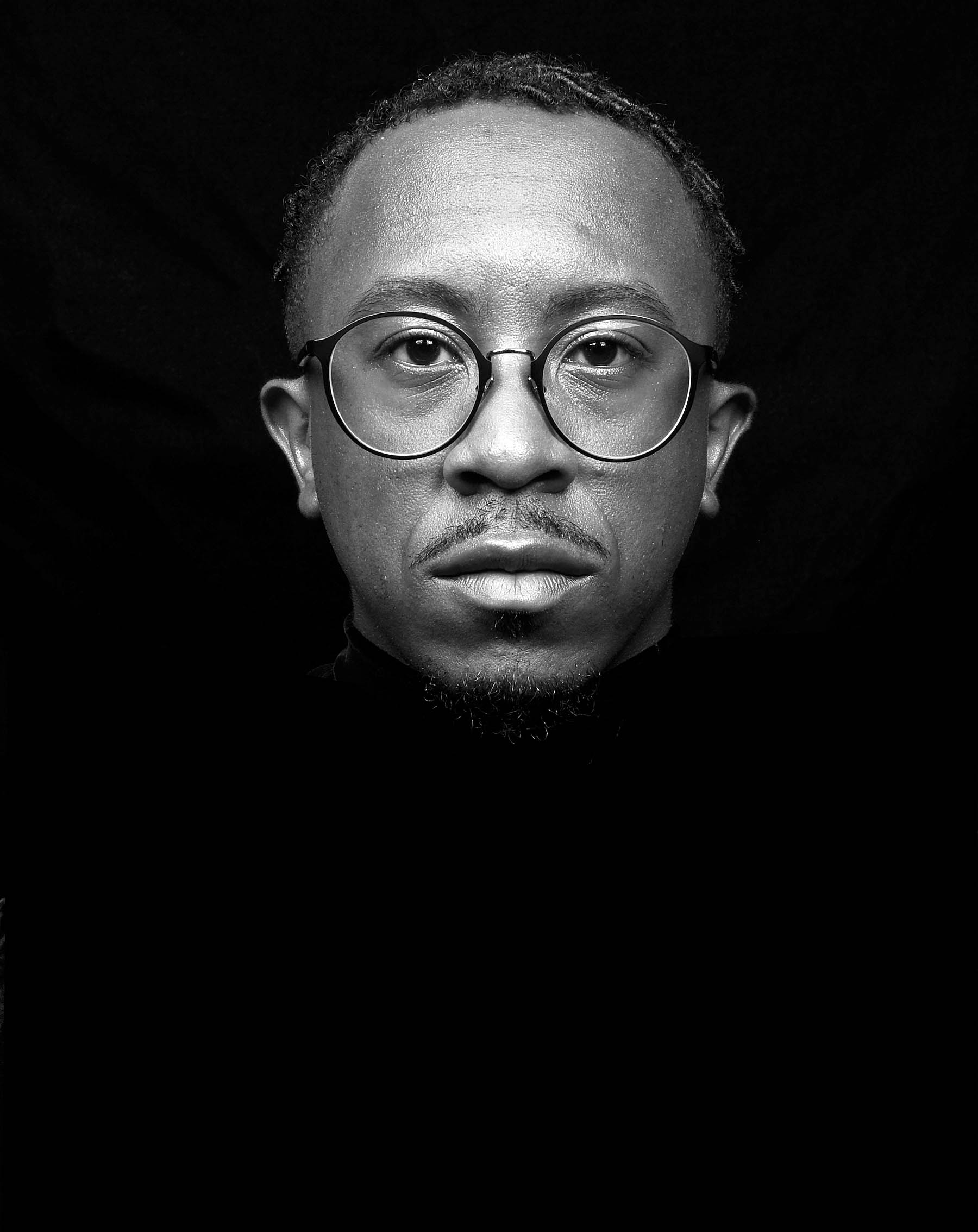

Like Women of a New Tribe, this is a traveling exhibition that has different iterations at each host venue. Here, community members nominated men who had impacted Flint in a positive way, and these individuals became the subjects of the exhibit. Entering the gallery space, visitors first encounter a set of black and white photographs of each individual, and text on the wall poses the question “Who do you see when you look at me?” Each subject meets the camera’s gaze, unsmiling. Everything below their chins is cropped out, and their heads seem to hover in indeterminate space. The absence of any props or details invites viewers to encounter each face at, well, face value, and try to read the furrowed brows and creased foreheads for some hint at deciphering their respective stories and personalities.

Courtesy of the Flint Institute of Art and Jerry Taliaferro

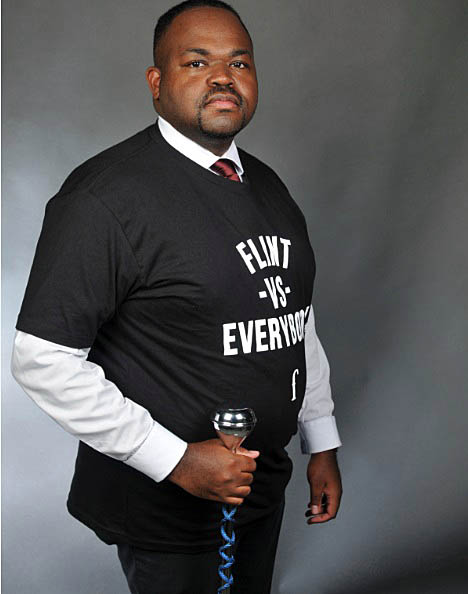

This first series of images is answered with a second set of larger color photographs, and accompanying text on the gallery wall declares “I Am…” The same men pose for three-quarter portraits this time, sometimes whimsically (though always dignified), and the clothing they wear and the props they carry offer us substantially more insight into who these individuals actually are. Unlike the first series, these photographs are accompanied with the name and a brief biography of each individual. All deeply involved in their respective communities, these men are teachers, pastors, businessmen, entrepreneurs, musicians, philanthropists, volunteers, husbands, fathers, and sons.

Careful and thoughtfully posed compositions assist in the visual storytelling to elevate these images beyond a photographic directory of Flint’s Who’s Who. And there is thoughtful conceptual significance in presenting these two parallel sets of portraits. Taliaferro writes, “As a Black American male I have sensed the discomfort of others (and myself) in certain encounters, I have also been amazed how this discomfort dissipates as we learn more about one another and discover the many things we have in common. This simple exhibition is a humble attempt to dispel some of the fear and discomfort.” Indeed, after we’ve learned about these individuals and heard their stories, returning to the first set of photographs seems like returning to old acquaintances, and the exhibition invites us to reflect on the ways and the frequency with which we subconsciously and baselessly draw conclusions about individuals.

Courtesy of the Flint Institute of Art and Jerry Taliaferro

Courtesy of the Flint Institute of Art and Jerry Taliaferro

Drawing from Life, a concurrent (but unrelated) exhibition in the FIA’s single-space Graphics Gallery complements Sons with an exhibition of socially and spiritually resonant drawings by Ed Watkins, a Flint native who taught at the Genesee Area Skill Center and Mott Community College. The show takes its title both from the artistic practice of drawing from life, and also from Watkins’ philosophy of art, for which his creative practice is guided by his lived experience as a Black artist, and the Black experience is central to his work.

Courtesy of the Flint Institute of Art and Ed Watkins

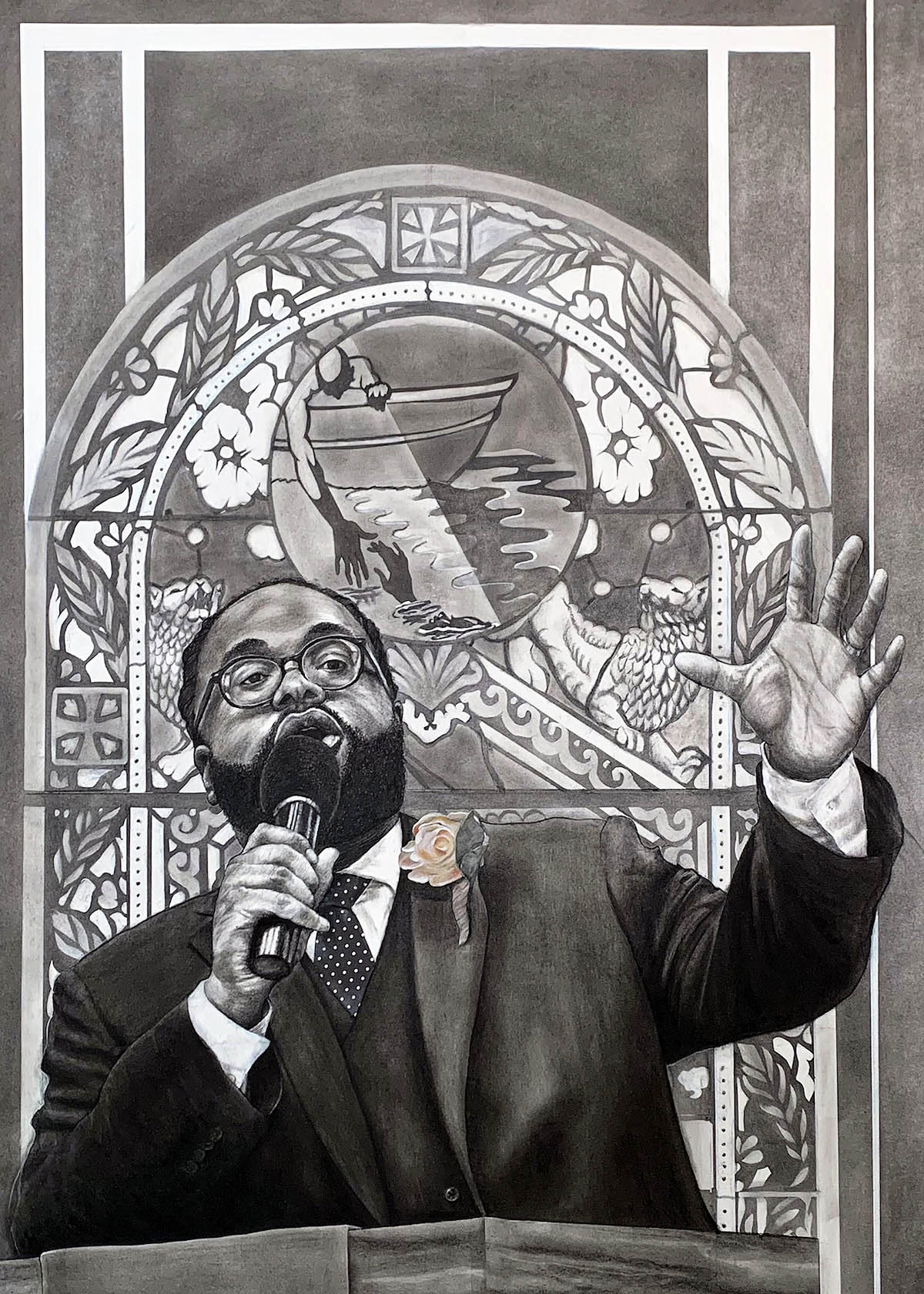

Watkins’ ambitiously large drawings employ a visual magic realism; his figures are rendered with exquisite draftsmanship, and elements within his drawings add layers of symbolism and allegory. His drawings stylistically rhyme with the works of Chicago’s Charles White, whose drawings were also rendered ambitiously large and applied tight, representational draftsmanship relentlessly underscored by faith and a yearning for justice.

Some of his most socially resonant works are those inspired by the recent police shootings of Michael Brown (Surrender Jonesz) and the death of George Floyd (Breathe), the latter of which portrays Tristan Taylor, organizer of the “Detroit Will Breathe” march in the summer of 2020. Taylor’s face is largely covered by his facemask, but Watkins captures his impassioned eyes and furrowed brow, which speak to the moral weight of his cause.

Faith informs many of these images, some of which are richly freighted with spiritual symbolism. The Ravens: I Kings 17 depicts a volunteer distributing cardboard boxes of food to unseen recipients while under the watchful eyes of nearby ravens. The work references the Biblical story of Elijah, miraculously sustained in the wilderness by ravens who brought him food. It’s an image also inspired by the toll the Covid pandemic took on individuals suddenly displaced from their jobs, and the churches and community organizations that distributed provisions to the food-insecure.

The four works on view from his Preacher series are particularly forceful. Sometimes rapturously animated, sometimes soulfully contemplative, but always expressive, these drawings portray pastors, including some from the Flint area. Watkins tactfully uses the stained-glass windows in the background to underscore the content of the sermons which directly inspired each work. Most of these drawings show each preacher mid-sermon, but his portrait of Marvin Jennings (Sr. Pastor Emeritus of Flint’s Grace Emmanuel Baptist Church) captures the subject in a moment of solitude and quiet reflection, the stained glass panels in the background portraying Ghanaian symbols for peace, unity, and other virtues.

Courtesy of the Flint Institute of Art and Ed Watkins

Courtesy of the Flint Institute of Art and Ed Watkins

Taliaferro’s photographs and Watkins’ drawings are most rewarding when viewed in person, where their comparatively large scale can be best appreciated. But much of Taliaferro’s show can be accessed digitally, including video interviews of each of the men featured in Sons. While each of these two exhibitions apply different media to explore different facets of the Black experience, they certainly pair well together. Both shows are imbued with social relevance, and each is fortified by quiet dignity and relentless optimism.

Sons: Seeing the Modern African American Male is on view at the Flint Institute of Art through April 16, 2022.

Drawing From Life: Ed Watkins is on view through April 10, 2022.