Right now in Chicago, there is probably more Cezzane under one roof than anywhere else in the world. The Art Institute of Chicago goes big with its special exhibitions, and its current offering of works by Cezanne is a beast of a show, comprising 80 paintings, 20 watercolors, two sketchbooks, and a smattering of pencil sketches, and together they demonstrate the artist’s stylistic and thematic breadth. This is Cezanne’s first American retrospective in 25 years, and it brings together works from collections in North and South America, Australia, Europe, and Asia. The show emphasizes Cezanne’s multigenerational appeal; lauded after his death as the “father of modern art,” his paintings (including many on display) were owned by well-known 19th and 20th-century artists, and his enduring reach extends to the present day.

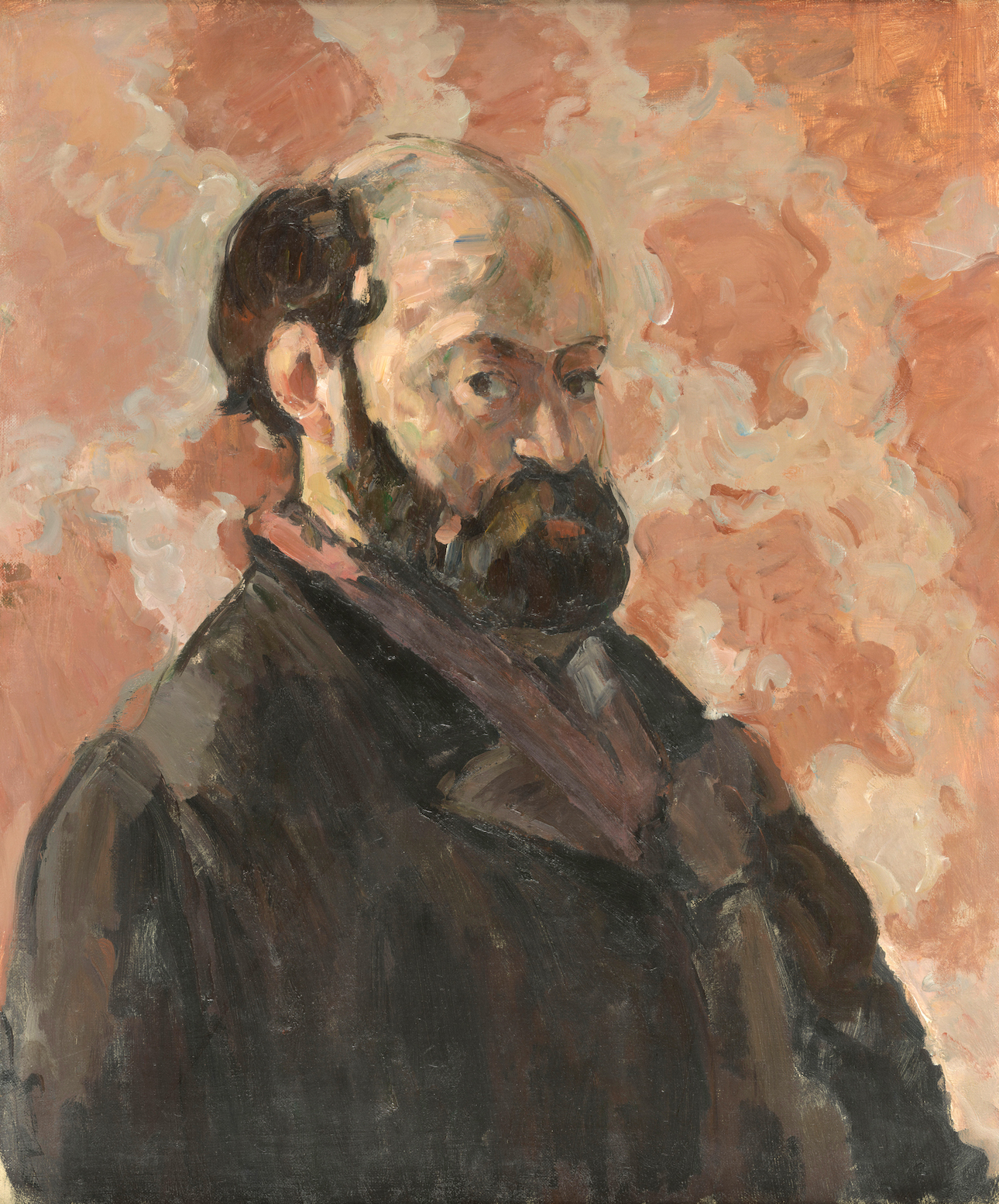

CÈzanne Paul (1839-1906). Paris, musÈe d’Orsay.

Although Cezanne was never formally accepted into art school, he was firmly rooted in art historical tradition, and he studied the masters of the past. When he moved to Paris in 1861, he frequented the Louvre, which he once described as “an open book I am continually studying.” There, he studied and copied Renaissance and Baroque paintings and sculptures. Several early graphite drawings on view demonstrate his ability to draw the figure in a classical, academic style. These tightly rendered drawings are contrasted in the same room with other early experimental works from the 1860s in which Cezanne applies the paint thickly, using only a palette knife to scribble in his subject. These early works are suggestive of a versatile style and artistic swagger.

Cezanne’s vision brought new life to the centuries-old genres of still life painting and landscape painting, and in his hands the two could become strikingly similar, as a room of his increasingly busy still life paintings demonstrates. There’s nothing “still” about his still-lifes. Thoroughly unburdened by any adherence to linear perspective, these counterintuitive canvasses seem to heave and buckle. Add into the mix a tactfully arranged patterned tablecloth replete with ridges, furrows, and crevices, and the result is tabletop topography.

Still Life with Apples; Paul Cézanne (French, 1839 – 1906); 1893–1894; Oil on canvas; 65.4 × 81.6 cm 25 3/4 × 32 1/8 in.

Paul Cezanne. The Basket of Apples, about 1893. The Art Institute of Chicago, Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection.

Although he studied in the great museums of Paris, Cezanne self-styled himself as a provincial artist. He was born and raised in Aix-en-Provence, and he frequently left Paris to paint the region, geographically defined by the imposing limestone Mont Sainte-Victoire– the location of a second-century Roman military victory and source of local pride. Some of Cezanne’s most recognizable paintings are the serialized studies he affectionately painted of the angular mountain, mostly executed during the last fifteen years of his life. This exhibit presents over a dozen studies and paintings of the mountain, and they represent some of Cezanne’s most daring works. The individual brushstrokes of his paintings become an increasingly noticeable presence, and the clarity of the landscape dissolves into a mosaic of scrubbed-in patches of color. One of his aims was to “make the air palpable,” and in these paintings, he certainly succeeded. There isn’t any negative space in the most abstract of these paintings; the air itself is rendered with thick chunks of color. These paintings speak to Cezanne’s artistic philosophy, which held that a painting was complete not when it was finished in the conventional sense, but rather when it successfully achieved his personal artistic intent.

Paul Cezanne. Montagne Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine, about 1887. The Courtauld Gallery, London. © Courtauld Gallery / Bridgeman Images

But even while Cezanne pushed the boundaries of abstraction, leading the charge toward modern art, this show makes it clear that he retained a deep affection for the art of the past. He produced many paintings crowded with frolicking or fighting nudes that acted as contemporary responses to the fleshy Baroque-era Gardens of Love and Bacchanals by the likes of Titian and Reubens. Cezanne’s Battle of Love, in which pairs of abstract nude figures naughtily tussle in a pastoral setting, directly echoes Titian’s 16th century Bacchanal of the Andrians.

The exhibition concludes with the largest and most realized of Cezanne’s Bather paintings, a subject he returned to throughout his life (other similar, smaller versions appear elsewhere in the show). It’s an idealized scene; the models were entirely products of his imagination, and Cezanne rendered the landscape to compliment and answer the composition and movement of the models. Stylistically, these abstracted figures are emphatically modern, and it’s easy to see why they appealed to artists like Henry Moore, Pablo Picasso, and Henri Matisse, all of whom once owned some of the paintings presently on these walls.

Paul Cezanne. Bathers (Les Grandes Baigneuses), about 1894–1905. The National Gallery, London, purchased with a special grant and the aid of the Max Rayne Foundation, 1964.

Cezanne is sometimes described in print as a “painter’s painter.” Perhaps this is unfair since it suggests that the average person just won’t understand his work. But this exhibition gives non-experts plenty of reasons to like his art, whether for his relentlessly imaginative re-working of classical artistic tropes, or perhaps the sheer complexity of his still-life paintings. This exhibition demonstrates his artistic reach, and specialists and non-specialists alike will find the exhibit rewarding. The abundance of works on view amply demonstrates Cezanne’s indebtedness to the past, even as he challenged artistic conventions and boldly anticipated the art of the future.

Cezanne is on view at the Art Institute of Chicago through September 5, 2022.