Map of the Interior: Sarah Rose Sharp’s “Results or Roses” at UM Institute of the Humanities Gallery

Sarah Rose Sharp, Hand of Fate, 2019, screen print by Too x Nail, fabric, embroidery thread, charms, beads, etc., 11.5” x 6” x 2.5

During these Covid times, visual artists’ exhibitions have migrated to online locations, with mixed results. For some whose work is photographic or text-based in nature, the effect is hardly noticeable. But for artists making very tactile or three-dimensional work, like the artworks in Detroit artist Sarah Rose Sharp’s Results or Roses at UM Institute of the Humanities Gallery, much is lost in translation. I felt some guilty delight when the gallery curator, Amanda Krugliak, consented to open the gallery (now temporarily closed to the public during the pandemic) for my visit.

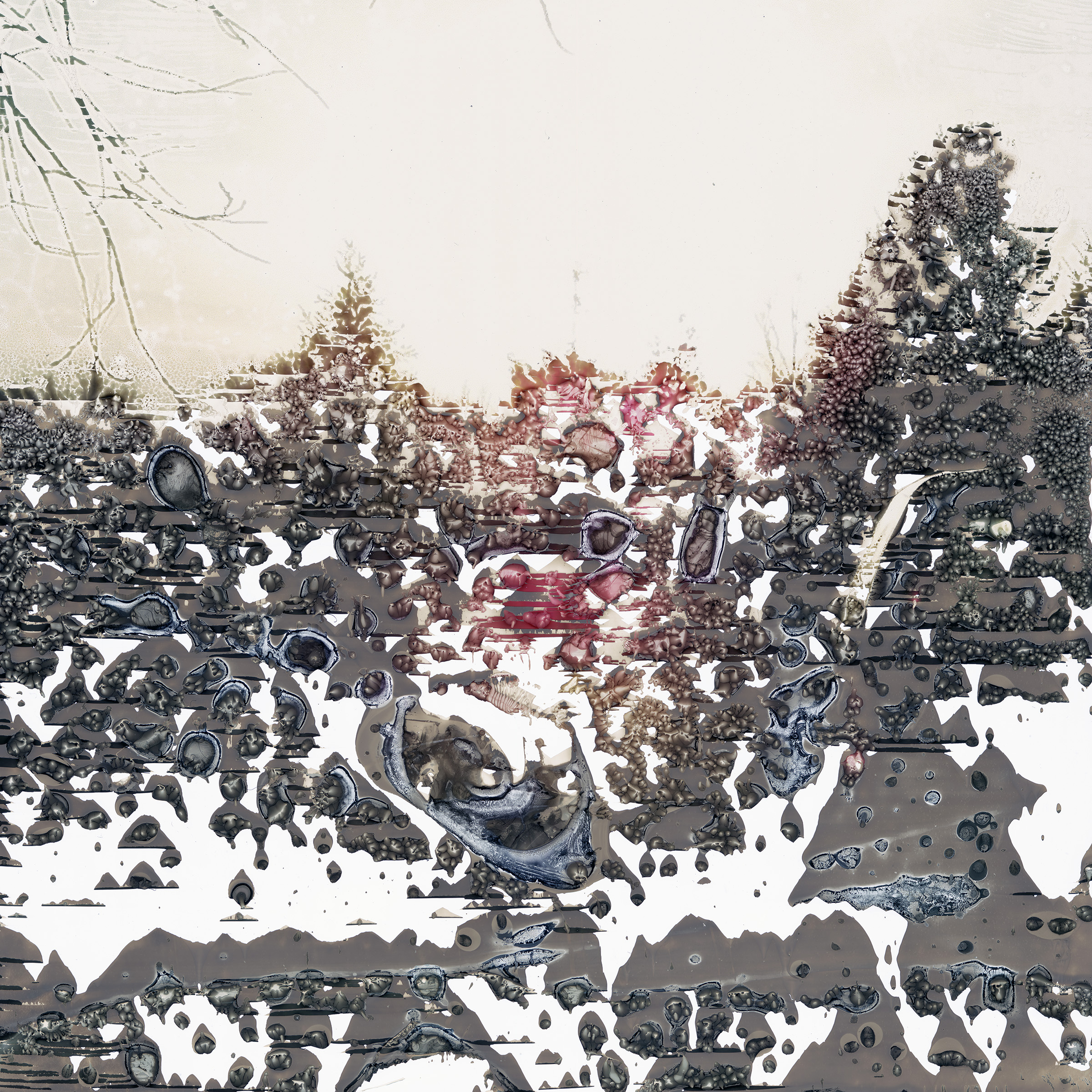

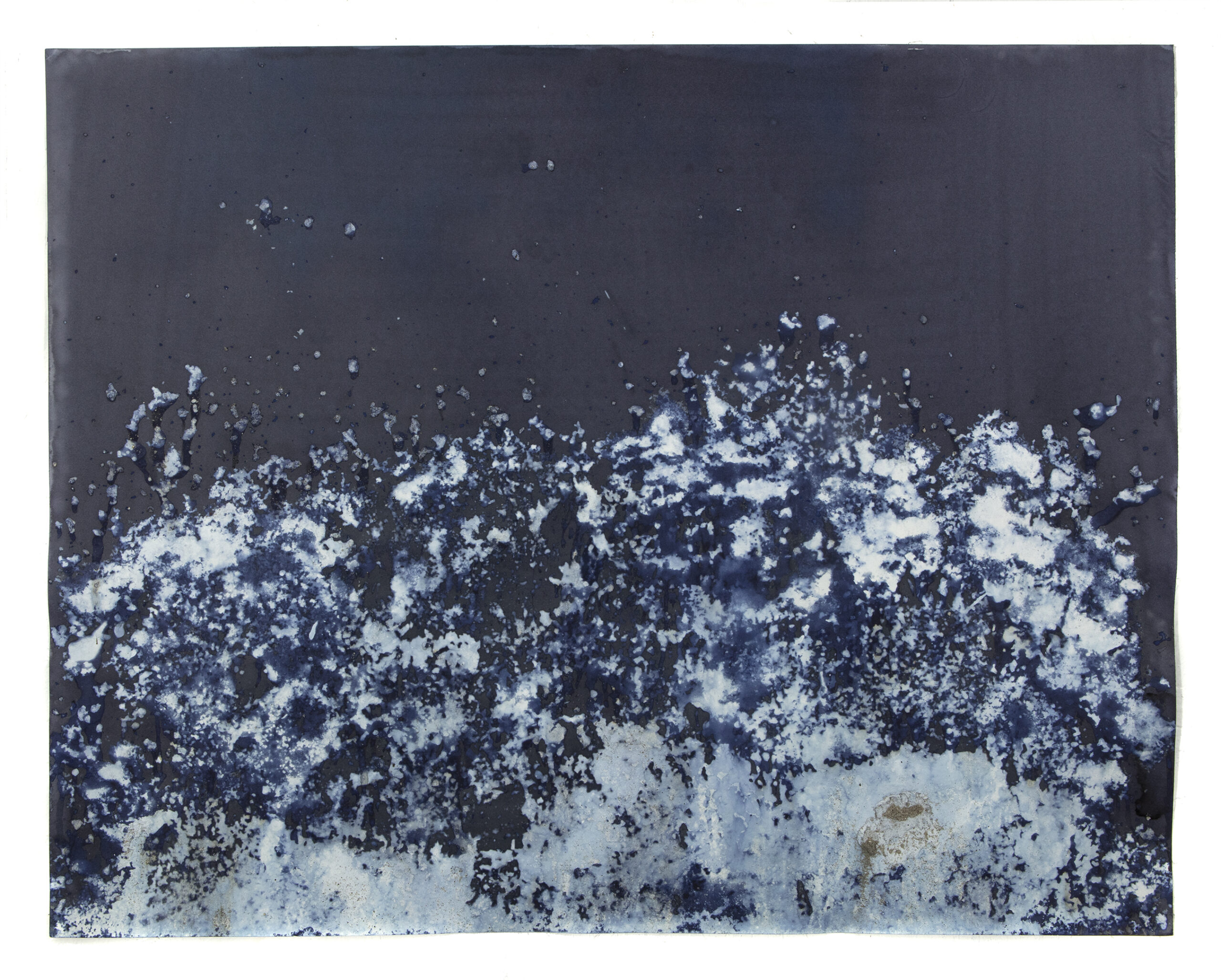

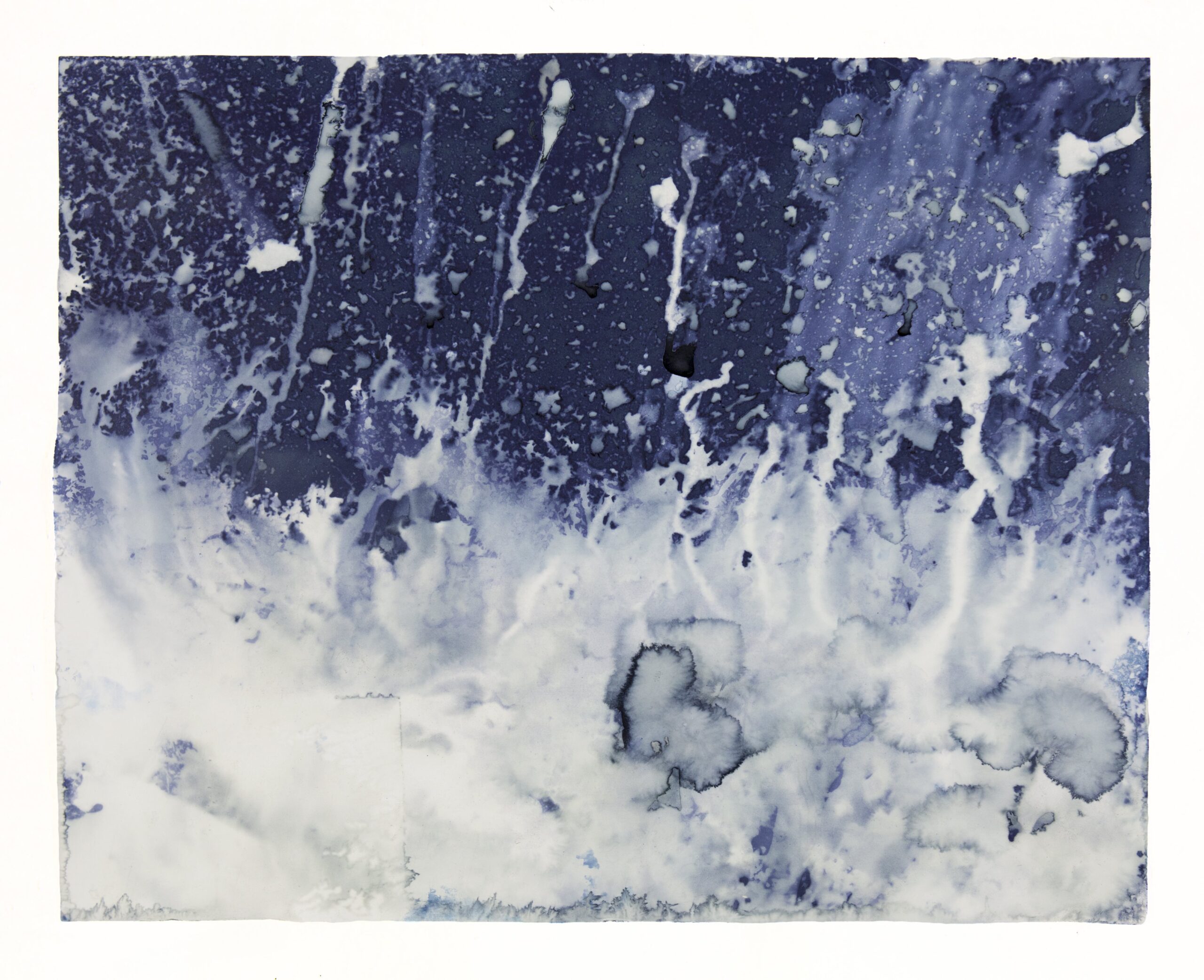

Sharp employs traditional needlework and sewing techniques to create a diaristic map of her interior life. The intimately scaled artworks illustrate several different trains of the artist’s thought and share the walls of the gallery and an adjacent vitrine, providing a virtual tour of the artist’s memories, observations and preoccupations. The overarching intention of the work seems to be located somewhere in the psychic territory between nostalgia and satire.

Sarah Rose Sharp, Immigrant Song, 2020, tablecloth by Rose Blaug, rice bag, embroidery thread, sequins, patches, beads, fake flowers, plastic table covering, etc., 24.75 x 24.75”

The modestly-sized but obsessively decorated wall hangings, flags, throw pillows–and some three dimensional assemblages too strange to name–add up to an untamed fantasia of tat and glitz. Sharp combines an improbable array of materials in her free-hand, free-associational compositions, some vintage, some newly minted. Found objects, beads, applique and embroidery seem to boil over the surfaces, threatening to encase the fabric ground entirely. Immigrant Song, perhaps the signature piece of the show, is a demented version of the Statue of Liberty, her single, oversized eye gazing out at the world and radiating energy. The surface is sequin-encrusted, and free-hand needlework decoration vies with store-bought embroidery patches for control of the surface. The fabric base for the artwork is part of a tablecloth that belonged to the artist’s great grandmother, which the artist cherishes as a meaningful collaboration with a woman she never met. Sharp has a real gift for the creative manipulation of materials, but is clearly more interested in their expressive potential than with conforming to any conventional notion of craft.

Sarah Rose Sharp, Target, 2020, fabric, arrow, handkerchief, t-shirt salvage, beads, sequins etc., 10” x 7.5”, arrow 29”

A native of California, Sharp devotes a number of her works for Results or Roses to both critiquing and humorously celebrating the Hollywoodized cultural signifiers of the West. In several pieces, she chooses mass market images of a heroic–and often imaginary–past: mustangs and buffalo, limitless deserts, child cowboys and cowgirls. In her flag-and–arrow assemblage Target, she deftly memorializes the near-demise of both Native Americans and buffalo herds, victims of America’s manifest destiny. In Native Daughter, Sharp makes a flag by embellishing a souvenir California handkerchief with appliqued and embroidered images that symbolize features of the state that may no longer exist. Jupiter Rising conjures an improbably limitless landscape of mountains, horses running free, a child cowboy and a pickup truck with a mysterious figure (Cowboy Jupiter?) presiding. From this work, it appears Sharp is still engaged in the unresolved process of locating her stance toward her childhood between appreciation and censure.

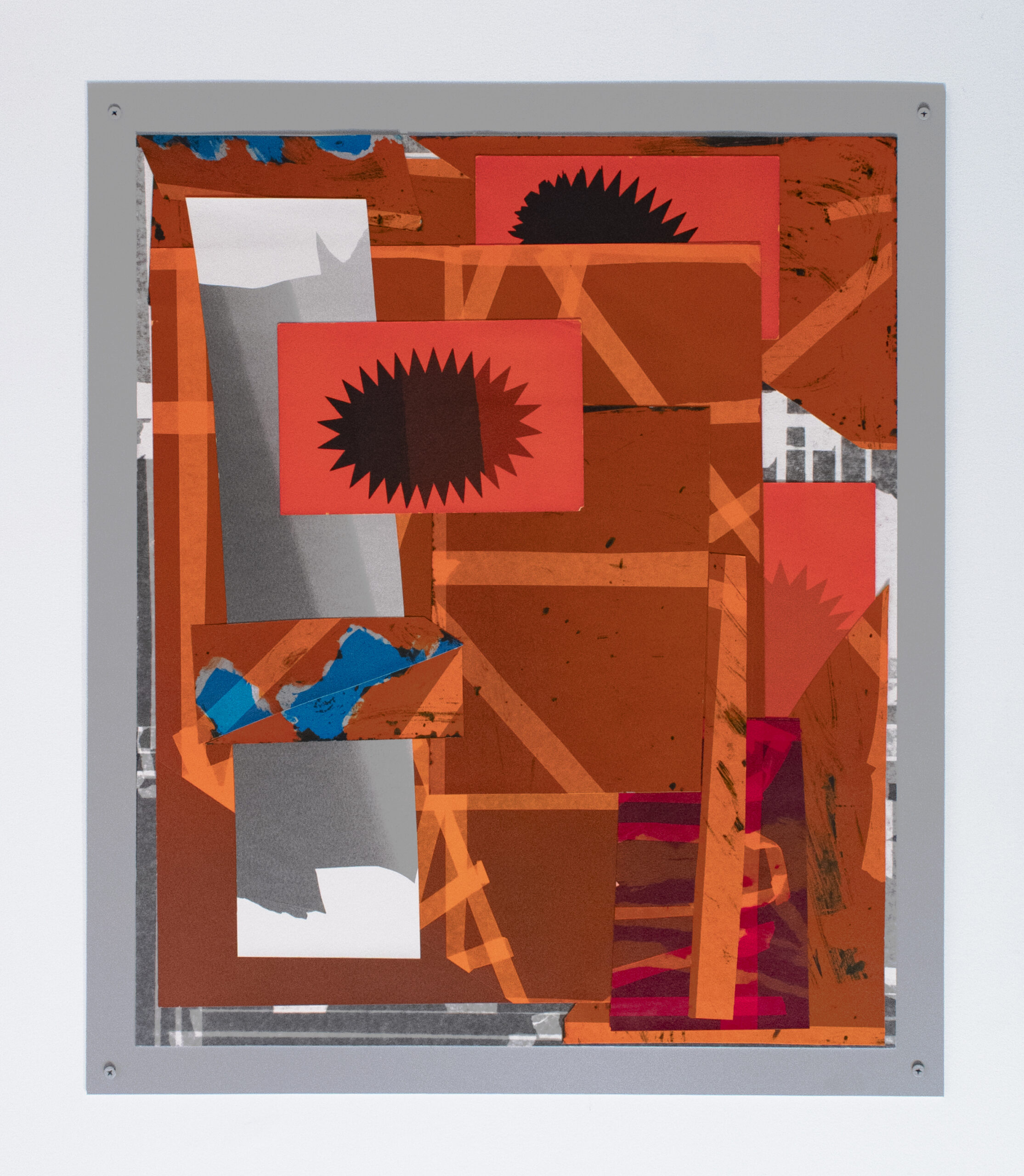

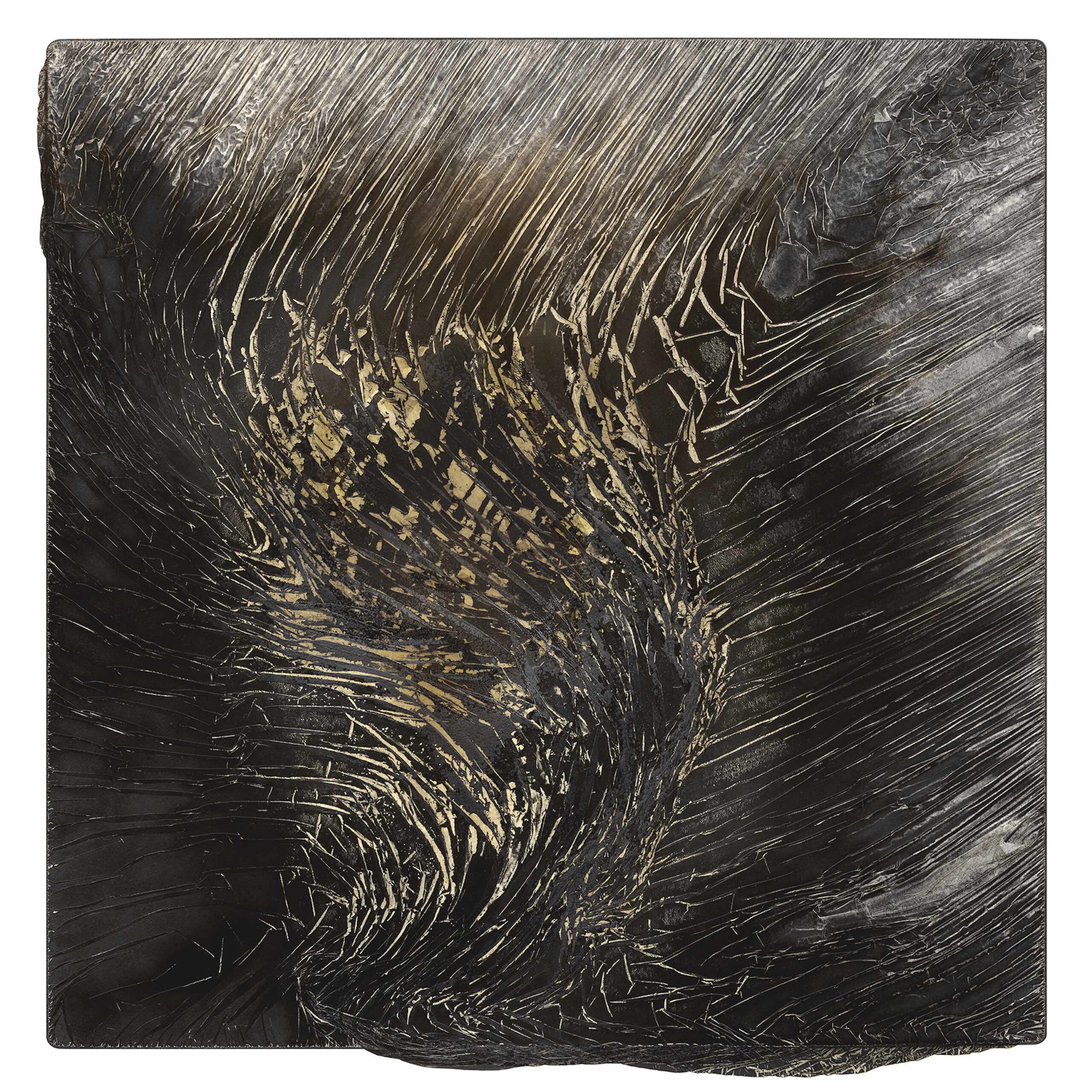

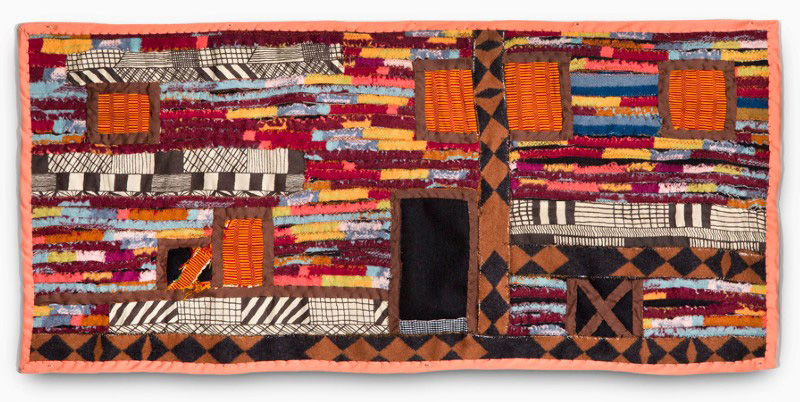

Sarah Rose Sharp, Detroit Patchwork IV, 2020, fabric, wool salvage, hem binding, corset wire, 32.5” x 15”

Sharp’s textiles referencing her more recent home, Detroit, are more straightforward appreciations of the substance of the city. She pieces together fabrics that describe architectural features, the voids and recent architectural additions, metaphorical renditions of the urban landscape as it stitches itself back together. Detroit Patchwork III is particularly evocative of the highways that span the city, while the fabrics she has chosen reference the ethnic diversity of its many neighborhoods. Detroit Patchwork IV may be the most formally satisfying of the series, a jubilant combination of oranges, browns and blacks that is slightly reminiscent of work by African American textile artist Carole Harris.

With each piece Sharp engages in an ongoing search for a legible reality from found bits and pieces of her life, past and present. Her question: are the symbols and images we get from mass media legitimate signifiers of some larger reality, or do the small, observed details painstakingly stitched together each day deserve equal weight in our construction of our own history and identity?

UM Institute of the Humanities Gallery

This review is re-printed with permission from Pulp, the Ann Arbor District Library’s online culture magazine.