Together & Apart: A Legacy of Abstraction at the David Klein Gallery, Detroit.

An installation shot from the opening of Together & Apart: A Legacy of Abstraction at the David Klein Gallery in Detroit, up through July 22. All images courtesy of David Klein Gallery

The abstract revolution that rocked New York City and the art world in the late 40s and 50s was, famously, a mostly male affair — in the popular narrative, at least, a testosterone-fueled explosion of masculine energy and creativity.

Except, of course, there were women working in abstraction and producing epic work at the same time, like Lee Krasner, Louise Nevelson or Helen Frankenthaler. They just didn’t get the headlines, a phenomenon Mary Gabriel explores at length in her 2018 book, “Ninth Street Women.”

Rebutting the notion that abstraction and machismo are connected at the hip, the David Klein Gallery in Detroit is hosting Together & Apart: A Legacy of Abstraction, which will be up through July 22. The Klein show spotlights four artists – Elise Ansel, Caroline Del Giudice, Alisa Henriquez and Rosalind Tallmadge. (The title, Together and Apart, comes from a Virginia Woolf short story from 1925 that explored artistic affinity among several women friends.)

“In the history of American art,” said gallery director Christine Schefman, “the New York school is where abstraction happened, with all those macho guys – DeKooning, Pollack, and so on. There were women there, and some of them became quite successful,” she added, “but they were definitely secondary to the men. The men were the geniuses.”

The women on display at David Klein pursue very different paths, from painting-and-collage to welded steel geometric forms, to name two. Drawing from different genres was, of course, part of the fun of pulling the show together, but Schefman says the women work well in unison, with their differing visions bumping up against one another. “They all have,” Schefman said, stopping for a second to pick the right phrase, “a feminine take. When you see their work together, there’s a certain harmony.”

Rosalind Tallmadge, Oberon, Mica, glass beads, sumi ink, Caplain gold leaf and sequin fabric on panel, 60-inch diameter, 2023.

Brooklyn artist Rosalind Tallmadge works with the most-exotic materials in the show, including mica, glass beads, Caplain gold leaf and sequin fabric. The majority of these works-on-panel are round, giving the distinct impression of alien worlds seen from outer space — deeply fissured and cratered landscapes with a dull metallic glint, both otherworldly and surprising.

A 2015 graduate of Cranbrook, Tallmadge was featured in that institution’s 2021 retrospective, With Eyes Opened: Cranbrook Academy of Art since 1932. The artist lives and works in Brooklyn. She was the subject of a solo show, Terrain, at David Klein in 2021.

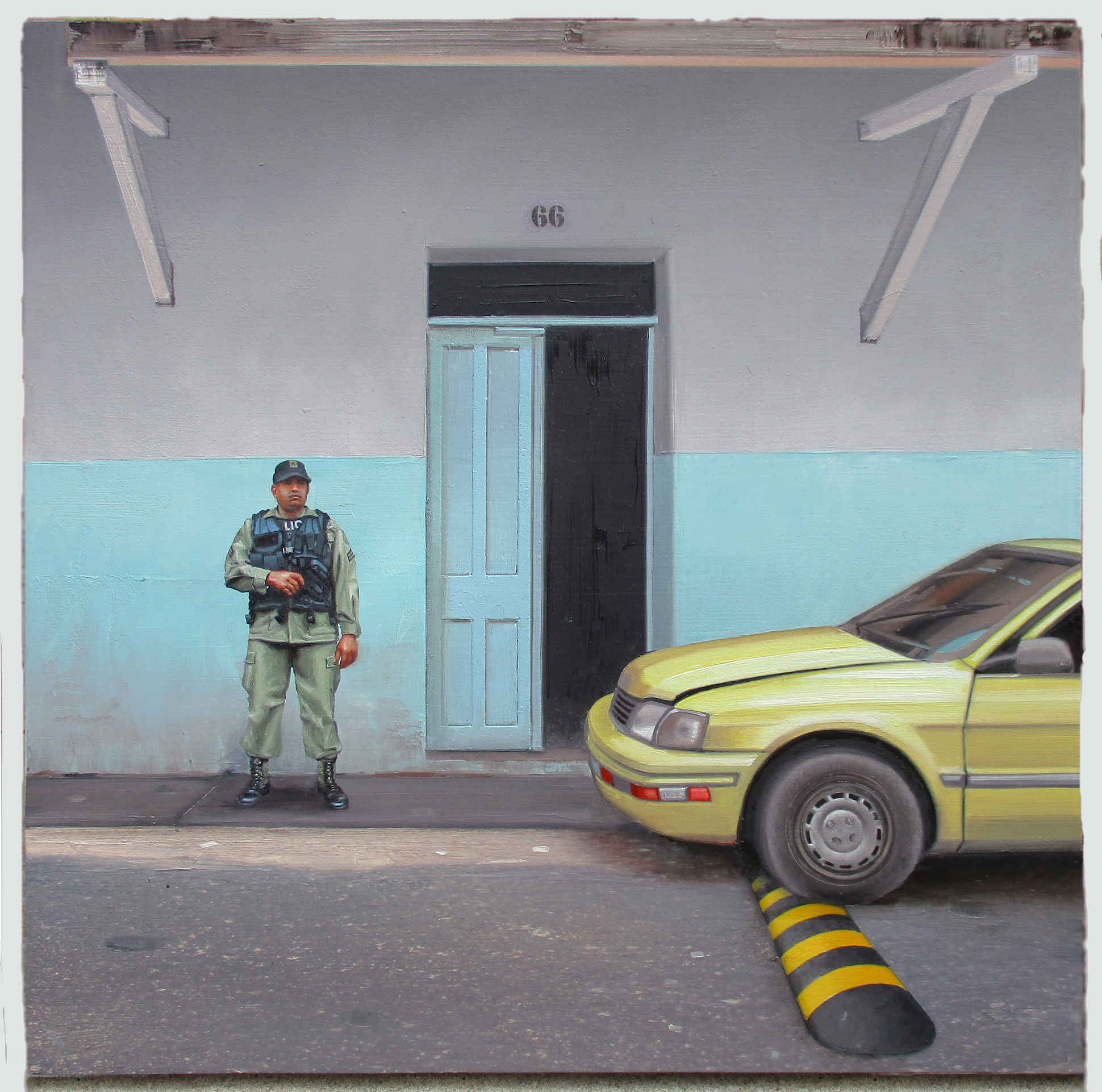

Elise Ansel, Obsidian Butterfly II, Oil on linen, 50 x 44 inches, 2022.

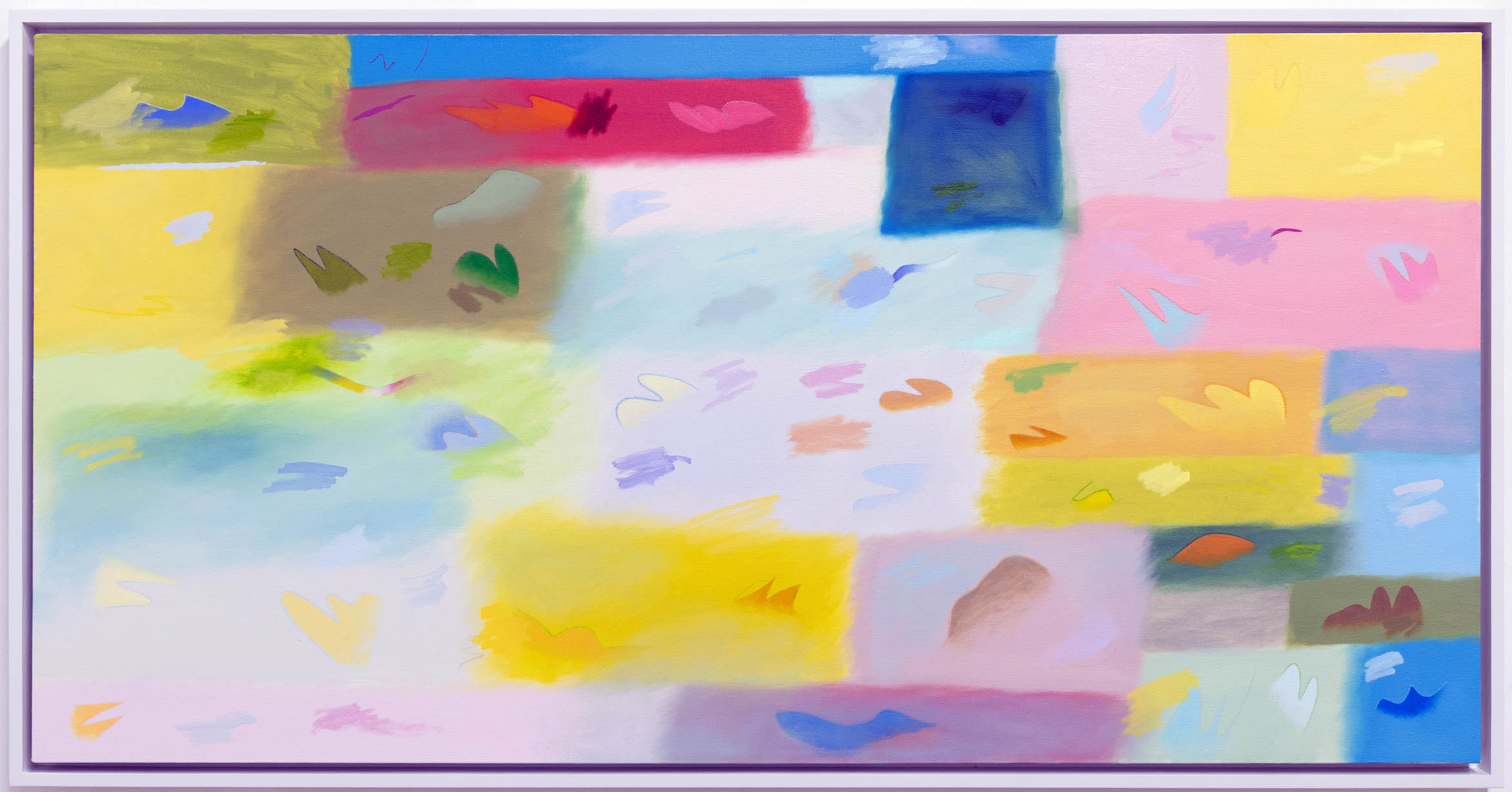

As an undergrad at Brown University, Elise Ansel fell back in love with Old Master paintings of the sort she’d seen as a child at the Frick Collection in New York City, and their drama and grandeur inspired her contemporary abstract oil-on-linen canvases – albeit reinterpreted and stripped of all figurative and narrative elements.

All the same, these canvases pack much the same emotional and visual drama, which Ansel, who got her MFA at Southern Methodist University, pumps up with deft use of color, and gestural forms that often appear to be in motion.

In editing out stories from great masterpieces, Ansel universalizes the pieces, broadening their possible meanings. She also, perhaps, feminizes the great masterpieces of yore, at once creating images both subtle and evocative – with not a Great Man in sight.

“I realized that these exquisite paintings were presented from the male point of view—as if that was the only one that mattered,” Ansel told Boston Magazine in 2022. With force and delicacy, the Maine-based artist succeeds in subverting the art-historical male gaze.

Caroline Del Giudice, Twirl III, Powder-coated steel, 24 x 29 x 25 inches, 2023.

Caroline Del Giudice, another Cranbrook grad, is a Detroit-based artist with a metalworking studio in Redford where she crafts a range of welded-steel sculptures. The three brightly colored distorted arches that greet you as you enter read as massive, heavy objects – even though they’re actually only two feet tall and just a bit wider.

Each sports a great colored, slightly reflective surface – crimson, purple and yellow, respectively – that’s kind of magnetic, looking very much like some industrial product of the highest order. And while their shapes describe a rounded arch of sorts, the geometry has been stretched, as it were, with one leg of the broken circle a step behind the other.

This contradicts your first assumption that these must be circular forms, at the same time that the staggered legs invest the structures with much greater visual stability. You could knock over a regular arch. Not these constructs. They stand their ground.

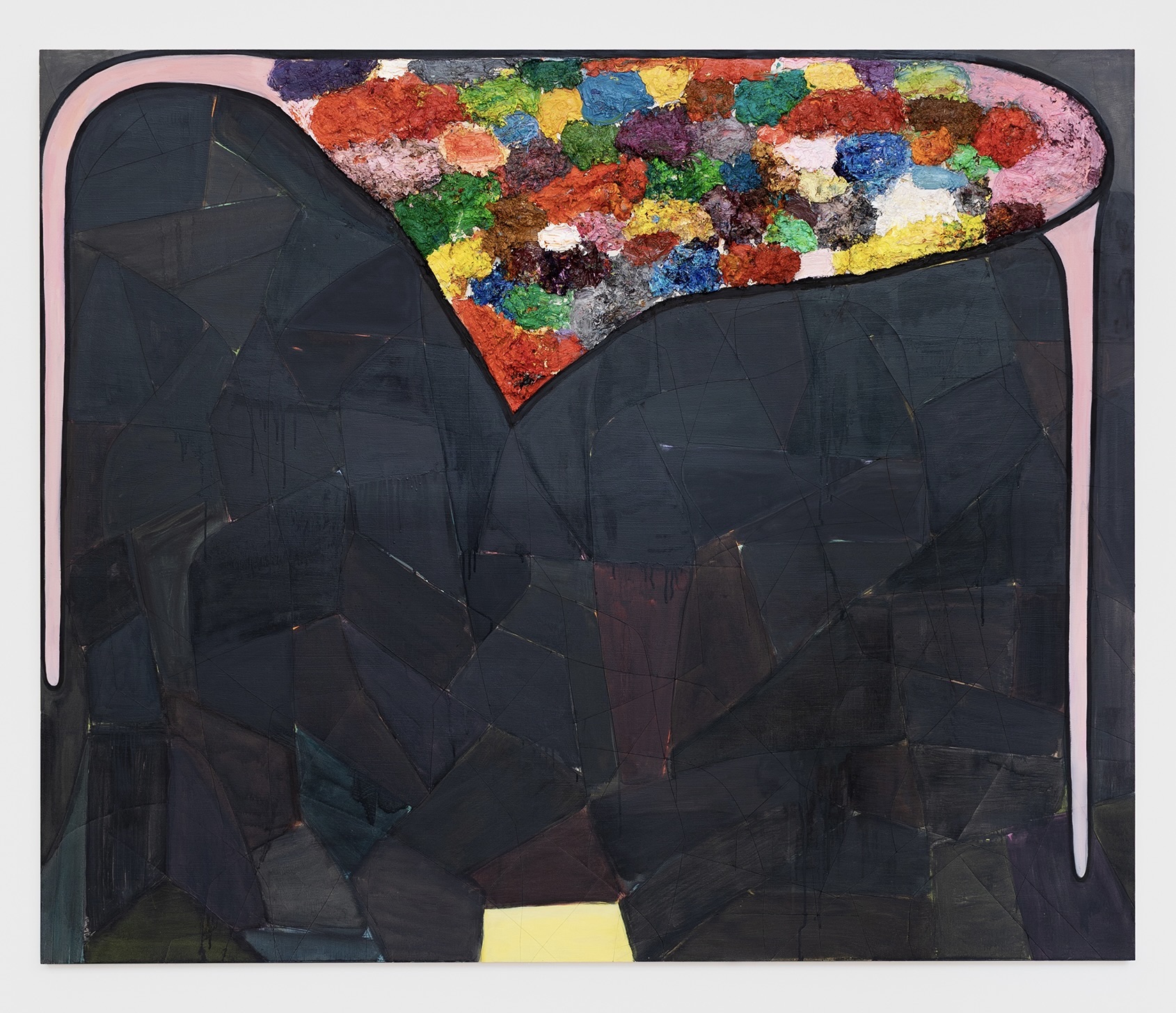

Alisa Henriquez, Sweet Nothings (detail), Acrylic, oil, digital prints, fabric and glitter on canvas, 63 x 53 inches, 2023.

Alisa Henriquez, who teaches at Michigan State University and got her MFA at the Rhode Island School of Design, in some ways gives us the most obviously feminine works in the whole show. At least, that’s the case with Sweet Nothings, in which a woman’s eye and fingers with painted nails play starring roles in this absorbing collage. The eye, in particular, is hard to avoid – just off-center and nicely done up in mascara, it stares out at the viewer with a questioning gaze that feels just a little sad.

In all six of her painted collages, Henriquez mixes colors with abandon, sketching out geometric objects and oddball shapes that often overlap or bleed into one another. These are crowded, active works – each quadrant, cut from the rest, could be a freestanding painting. In that sense there’s no real center, more of an intriguingly disordered visual universe.

Elise Ansel, Rosy Fingered Dawn, Oil on linen, 44 x 50 inches, 2022.

Together & Apart: A Legacy of Abstraction will be at Detroit’s David Klein Gallery through July 22.