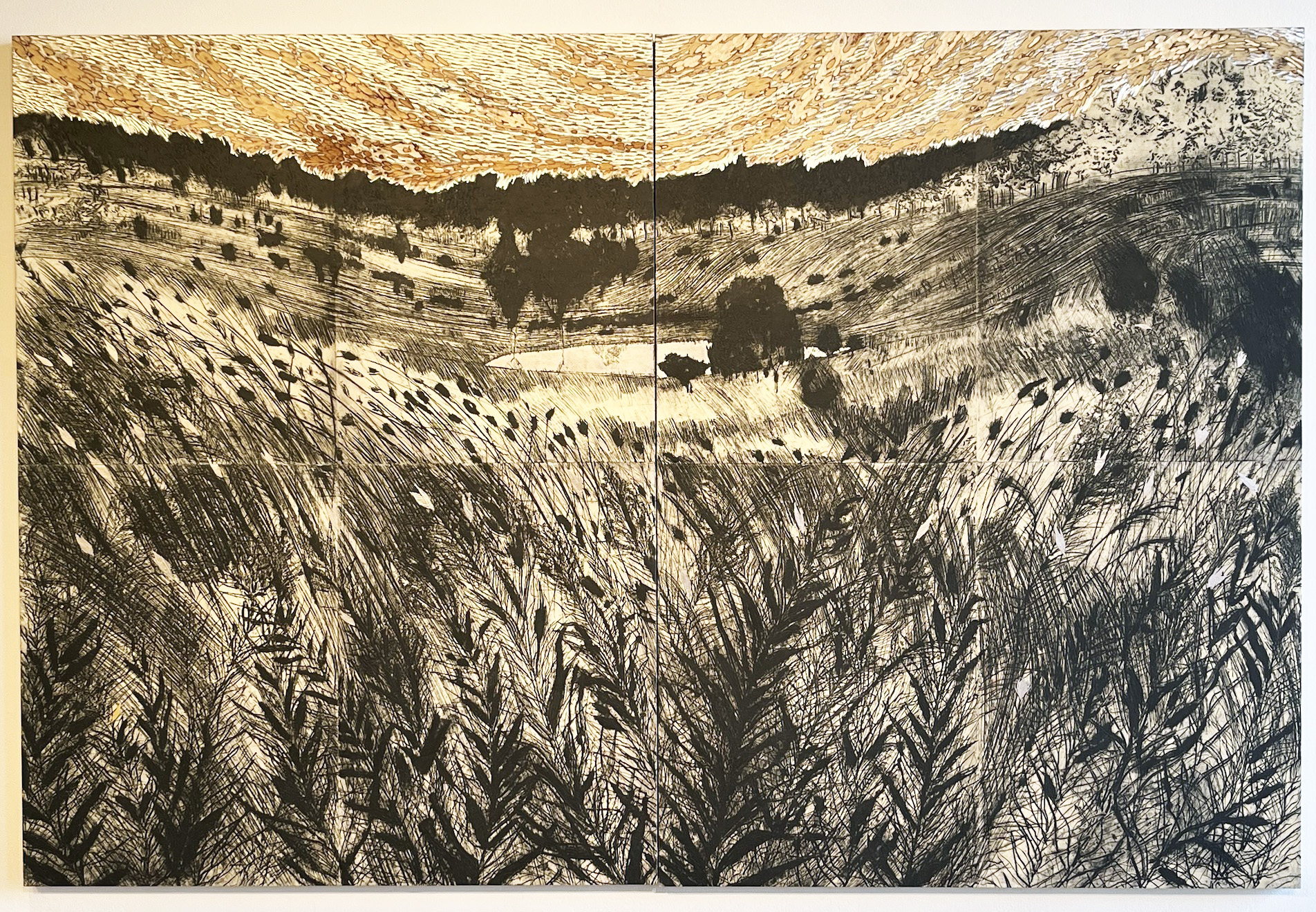

An installation view of Rick Vian: The Growth Habit at Ferndale’s M Contemporary through Feb. 18. Image courtesy of DAR

Over a long career, Rick Vian has alternated between two seemingly contradictory subjects for paintings. The first were breathtakingly realistic portraits of Upper Peninsula tree canopies and the sky beyond, later abstracted and given sharper colors in his Yellow Knife series in the late ‘teens. The second set of subjects, however, involve aggressive abstracts that call to mind both industrial processes and the power of elemental forms.

The engaging show at Ferndale’s M Contemporary, Rick Vian: The Growth Habit, falls entirely into the latter abstract basket, even as its title refers to trees and the shape and form each species will ultimately take. The growth habit suggests a certain inevitability – when unimpeded, the oak is destined to achieve a certain height, width and outline, characteristics that set it apart from all others. So too, apparently, with the paintings in this show.

The Growth Habit will be up through Feb. 18, when there will be a closing reception and an Artist’s Talk from 4-6 p.m.

When you boil it down, the dozen or so polyurethane-and-oil paintings hung here – which bear a glancing resemblance to the Russian Constructivists and Fernand Léger’s 1920s “mechanical period” – all come out of roughly the same mold. They’re action-packed, geometric abstracts. On occasion they’ve got an Escher-like quality, with three-dimensional shapes going places they simply can’t, while at other points, the geometry morphs into something more sculptural and biological in form. It’s a dualism that sets up an tense, interesting balance.

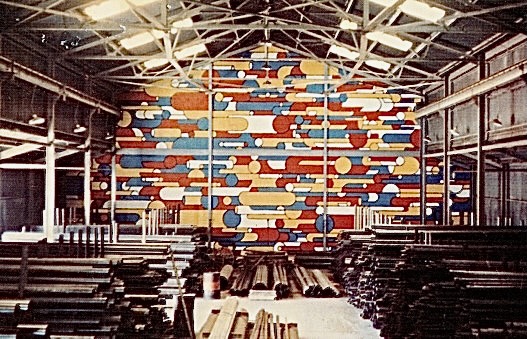

Rick Vian, Chickens in Bondage, II; Polyurethane and oil on canvas, 48 x 60 inches, 2021. Images courtesy of MContemporary Gallery.

There’s a dualism as well in Vian’s use of color. Works here alternate between a warm palette full of strong orange, black and vermilion, and a chillier one heavy on grays, whites, black, and occasional sharp-red details. Chickens in Bondage, II, once you get past the tongue-in-cheek title, is an absorbing color essay in tones of deep orange and red, all edged in black. As ever with Vian’s maze-like works, there’s a confusion of forms: Is that an individual on hands and knees somewhere near the surface, or the tail end of a chicken? And what’s going on with the big gear teeth over to the right? Bondage has more of a machine-like quality than most of the other paintings on hand, and the vibe isn’t entirely happy, either – not surprising, perhaps, given the realities of commercial poultry production.

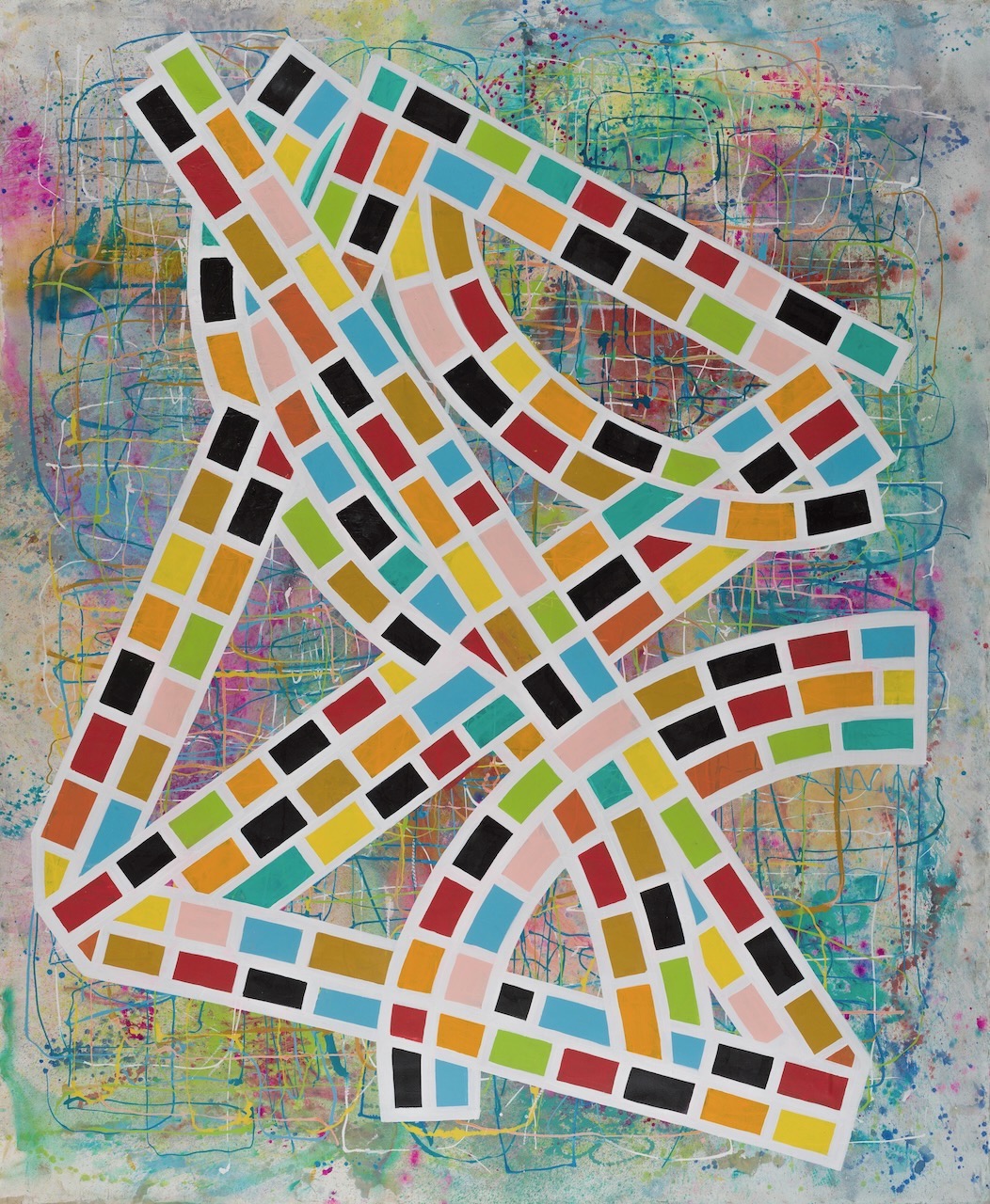

Rick Vian, Tell ‘Em Earl Lied; Polyurethane and oil, 72 x 60 inches, 2022.

M Contemporary owner and director Melannie Chard has had her eye on Vian for years and has always been a big fan. “Rick’s work is very energetic,” she said. “It’s got kind of a masculine feel to me — geometric but still organic, with that kind of play, that tension there that I find really interesting.” Indeed, both the mechanical and the organic fight for mastery on Vian’s canvases. This push-and-pull suffuses Tell ‘Em Earl Lied which, like most of Vian’s abstracts, seems to work simultaneously on several depth levels. There’s what’s going on at the surface, and then what’s partly obscured below, and then beneath that.

Rick Vian, Sex Machine; Polyurethane and oil on canvas, 15 x 13 inches, 2022. Image courtesy of DAR

Sitting on its own neat stack of cement blocks mid-gallery, is a much-smaller box painting, Sex Machine, one of several where the canvas wraps around all exposed surfaces. Thematically, there’s sort of a clamp-thing going on here. Three very similar “mechanical” devices — all of which look like they want to lock onto something, hard – march from stage left to stage right, setting up crosscurrents that pull much of the rest of the work with them, including what could fairly be described as a pair of abstracted Mickey Mouse ears.

Rick Vian, Horseshoes and Socks; Polyurethane and oil on canvas, 24 x 19 inches, 2022.

Vian, who did his undergraduate at Detroit’s School of the Society of Arts and Crafts (now the College for Creative Studies) and got his MFA at Wayne State, stands out among fine artists by having time spent in his past as a commercial and industrial painter. “That’s where some of his palette comes from — like ‘Safety Yellow’ and ‘Safety Red,’” Chard said, referring to stock industrial paint colors.

This series, she says, actually got its start way back in the early 1970s, but was put down for decades while the artist went in other directions. He picked it back up over the past couple of years.

Vian’s technique, Chard said, is “really intuitive. He doesn’t really know what he’s going to do when he starts. And I think that speaks to his other life as a jazz drummer.” Indeed, in a nice touch other artists might want to emulate — to blow off steam, if nothing else — Vian keeps a set of drums right at hand in his studio.

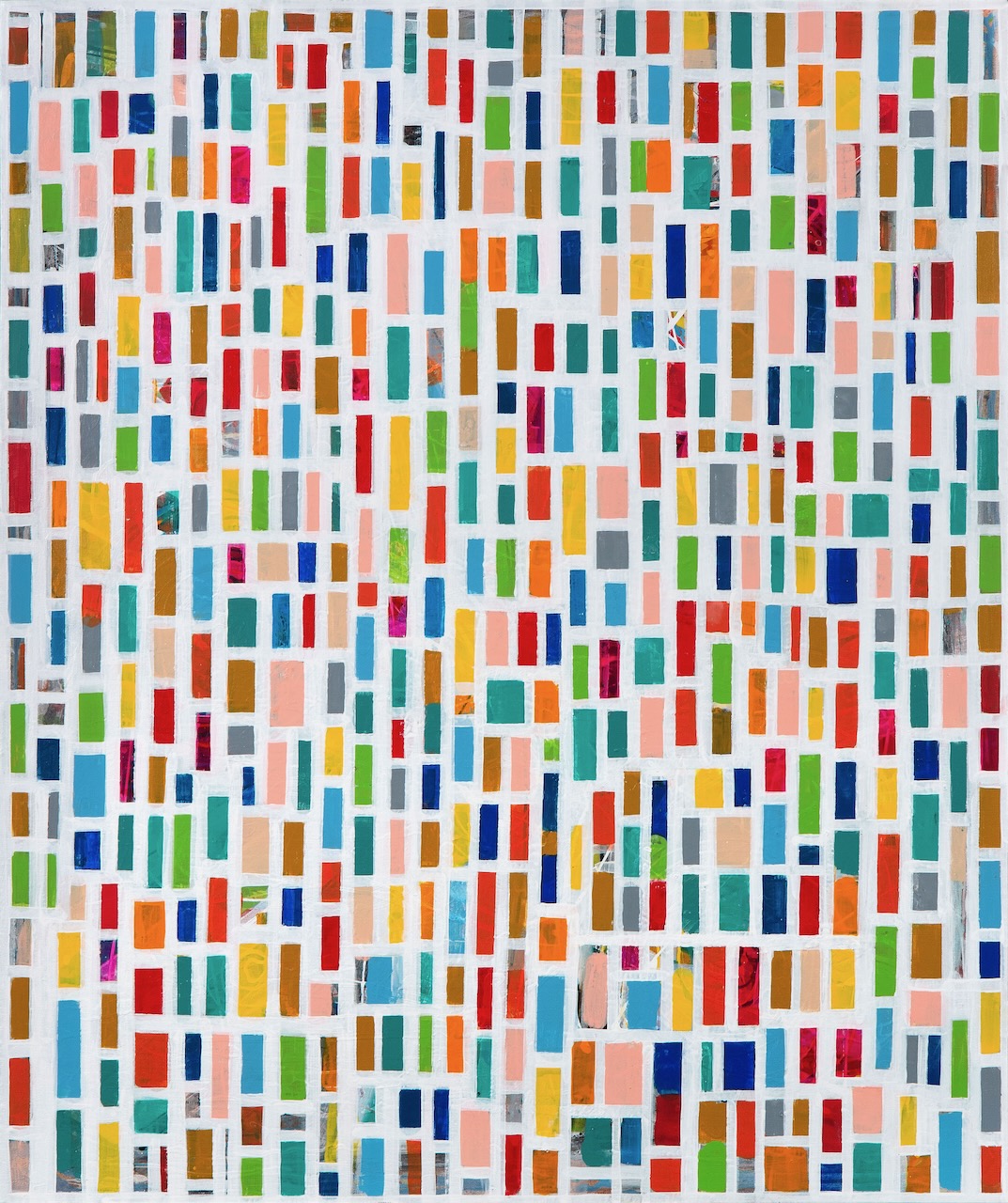

Finally, we’ll close with the one canvas that seemed, without question, to have some mordant humor flickering around its edges, Like Trying to Explain Wagner to a Dead Horse. It’s another of the chilly-palette paintings, with a lot of over-scribbling that gives it the look of a vigorous work in progress. But there’s no denying there’s something like a slumped body in the foreground, and, poking up into the air, a couple feet. It’s hard to shake the conviction they belong to the aforementioned dead beast.

Rick Vian, Like Trying to Explain Wagner to a Dead Horse; Polyurethane and oil on canvas, 18 x 24 inches, 2021.