“Mighty Real / Queer Detroit: Remembrance of Things Present” will be up at Detroit’s Scarab Club through July 9. The other 16 exhibition spaces will take the show down on June 30, 2022.

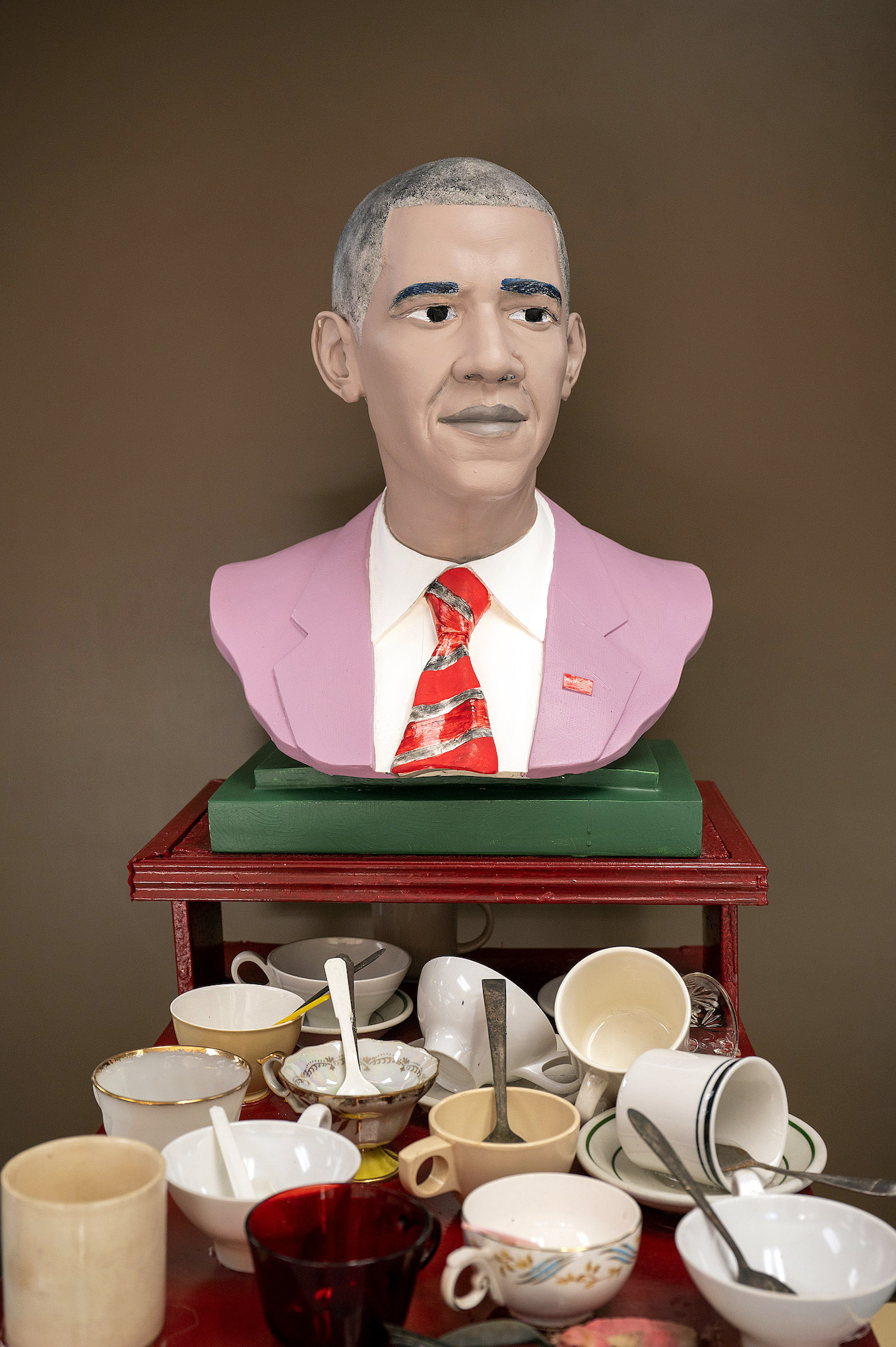

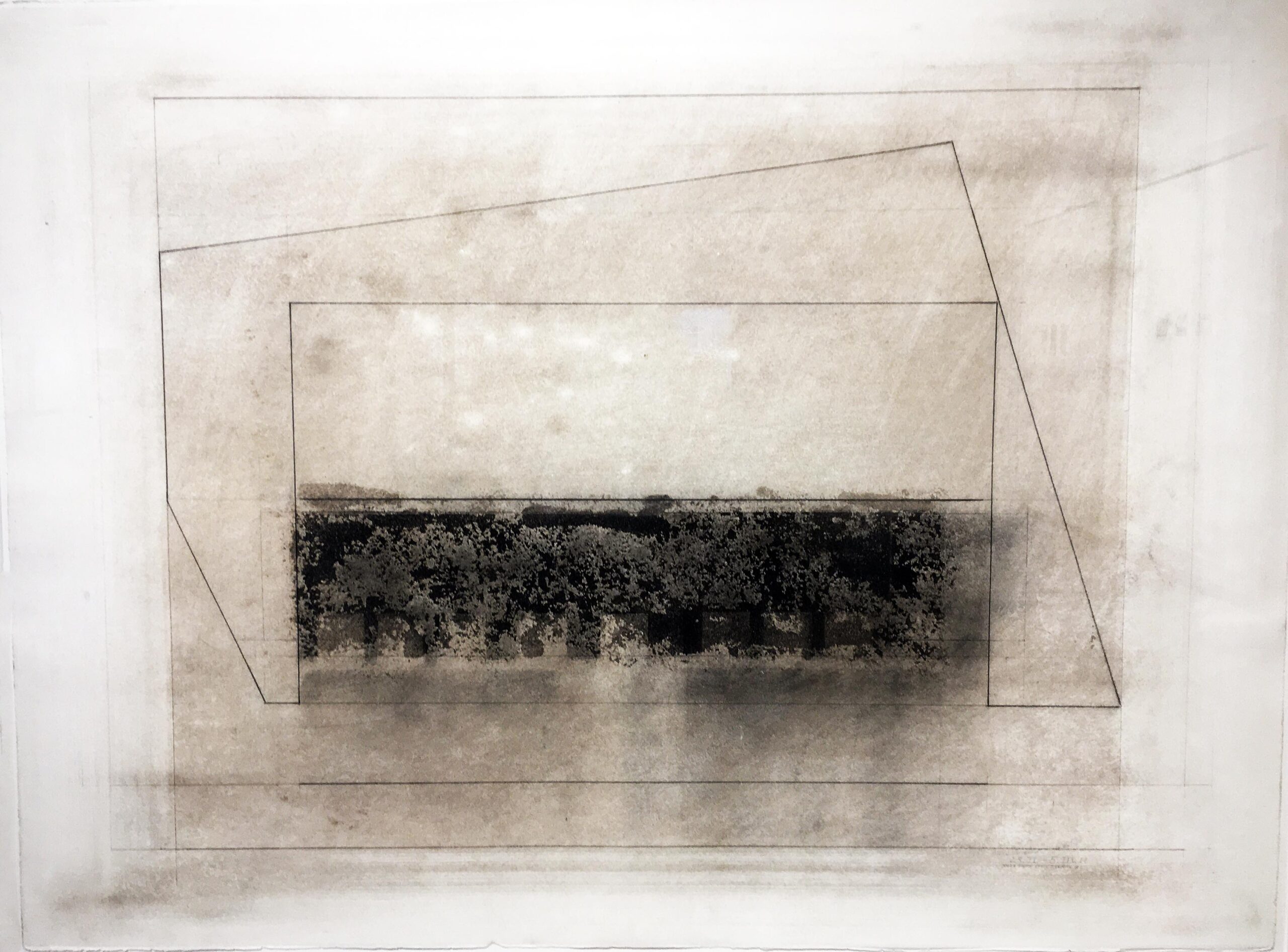

An installation view of “Mighty Real / Queer Detroit” at the Scarab Club, up through July 9.

“Mighty Real / Queer Detroit: Remembrance of Things Present,” the monumental art exhibition of LGBTQ art that sprawls over 17 venues, underlines just how much has changed in America in the new millennium. Even 10 years ago, this sort of mammoth undertaking devoted to queer artists and their allies would be hard to imagine outside of a few trend-setting cities, mostly on the coasts.

Boasting more than 700 pieces by 150 artists both established and emerging, as well as some who’ve passed on, MRQD is being mounted in partnership with the City of Detroit’s Office of Art, Culture, and Entrepreneurship.

The shows at participating galleries are up through the end of June.

Apparently sparked by a suggestion from Detroit artist and longtime gay activist Charles Alexander, the project was curated and muscled into glorious existence by Patrick Burton, a visual and performance artist who teaches in the Detroit schools. The exhibition was originally set for 2020, and at the time involved just four or five galleries. But two years of covid delays gave Burton time to extend his reach, pulling in other outlets all over town.

“Patrick did just a beautiful job putting together portfolios of work for all the different spaces,” said Treena Flannery-Erickson, gallery director at the Scarab Club. “It’s historic and amazing.”

Among the participating galleries are Hatch Art in Hamtramck, Detroit Artists Market, the David Klein Gallery and, out in Mt. Clemens, the Anton Art Center – said to have one of the liveliest displays.

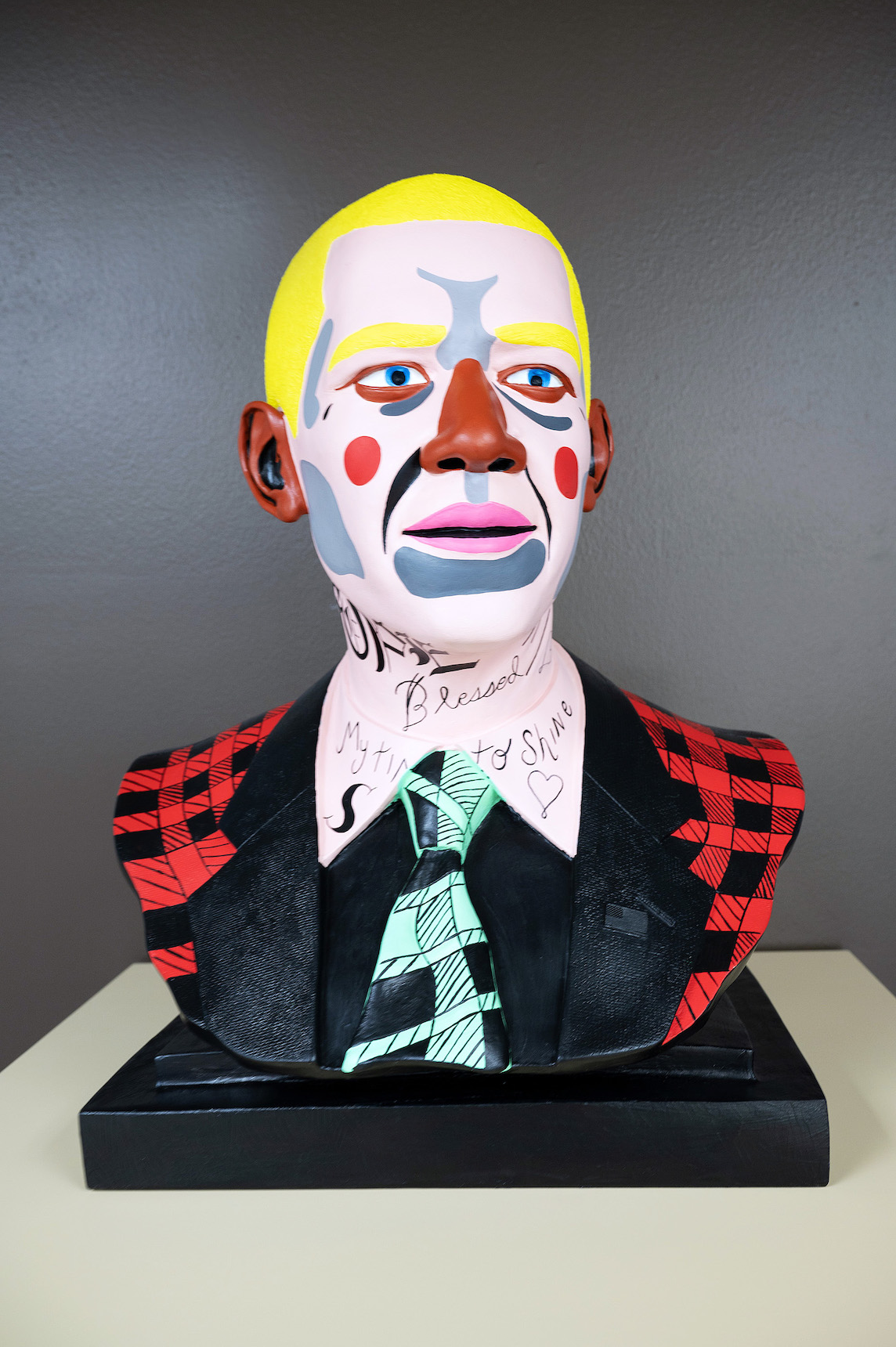

“This project is presenting queer artists, or humanizing us, in a new way,” Burton told The Detroit News. “We’re not often represented. We’re often sexualized and we’re not thought of us as full beings who live life and create art. This is about offering a queer culture and expanding minds and hearts.”

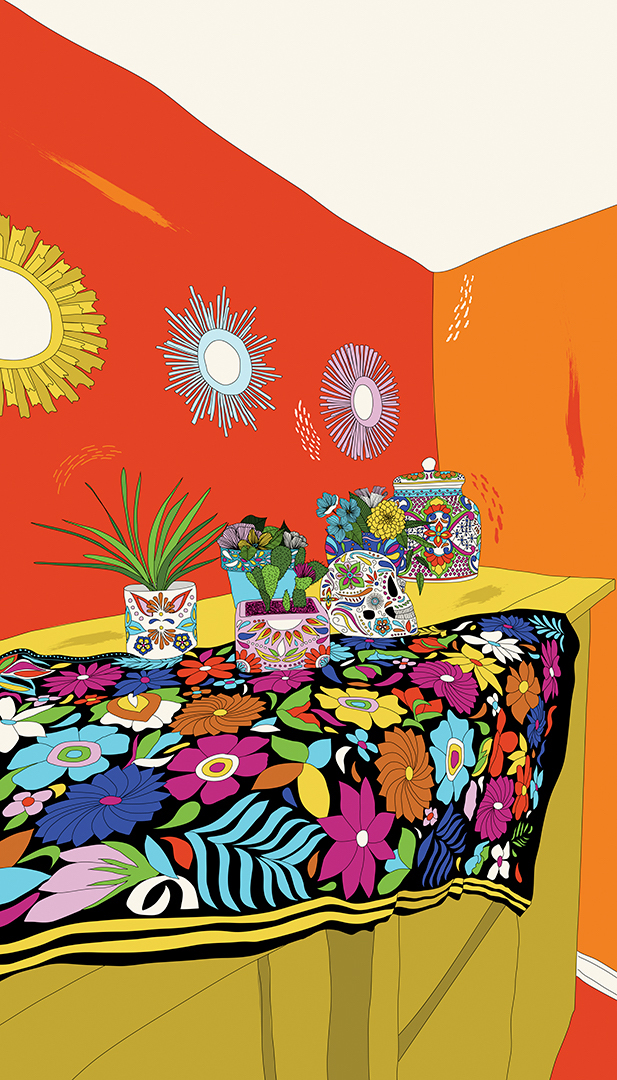

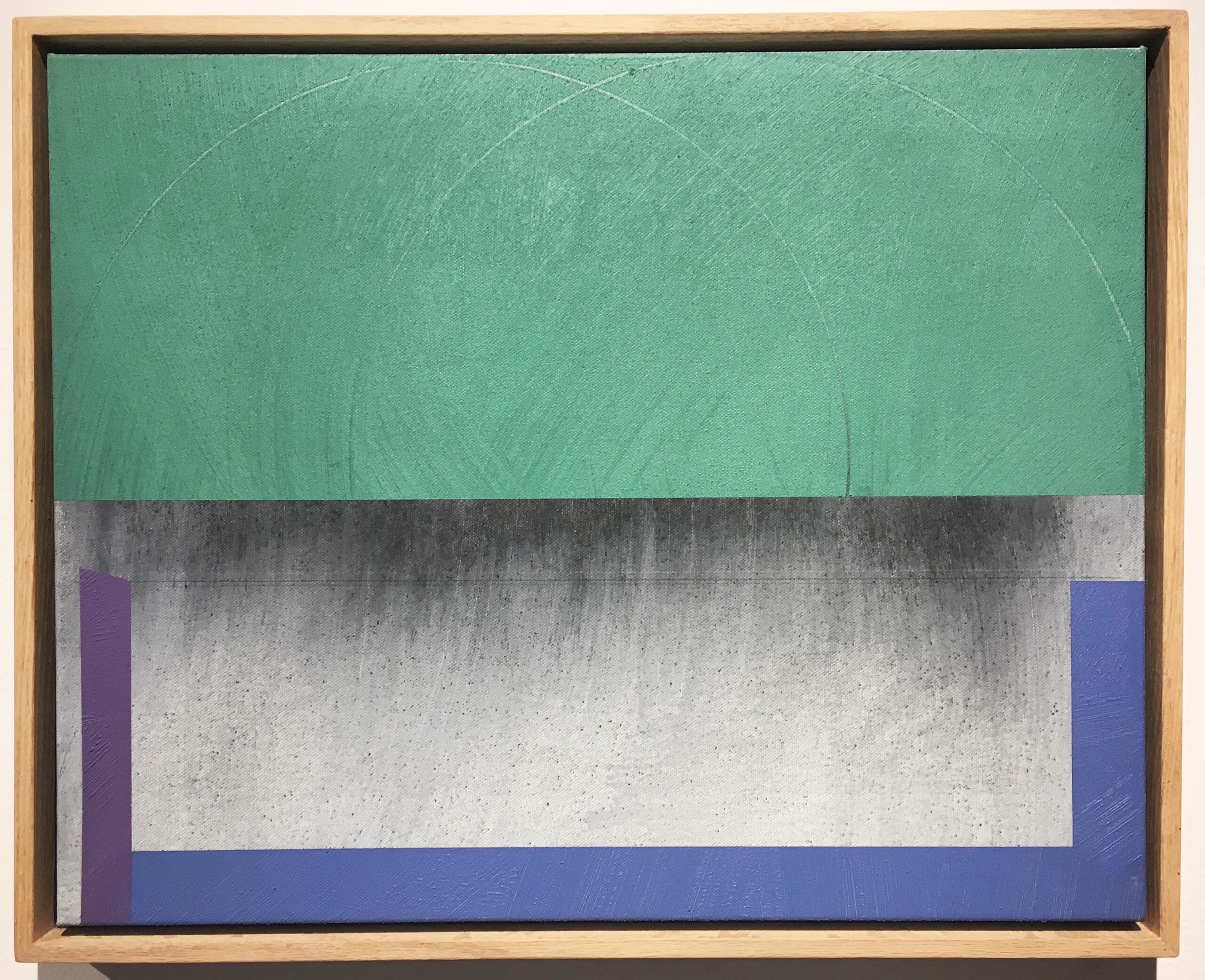

Stephanie Crawford, Green Still Life 3, Watercolor on paper, 22” x 15,” 2018. Courtesy The Scarab Club.

At Detroit’s Scarab Club, the 32 artists on view represent a wide and intriguing range of work, which will stay up longer than at other venues — through July 9. Some pieces here are thematically tied to the queer experience, like the late Jack O. Summers’ collage of itsy-bitsy naked men, while other canvases, such as the technicolor trio of still-lifes by Stephanie Crawford, a Black native Detroiter in her 80s, eschew messaging in favor of simple, striking beauty.

By contrast, the 1999 “Blue Bathroom Blues 1” by Frederick Weston, raised in Detroit before moving to New York, clearly points to the AIDS catastrophe. Look closely at this gorgeous, geometric collage in shades of blue and aqua and you’ll find a reference to the protease inhibitor Crixivan, an anti-HIV drug right beneath an advertising slogan, “Safe for Septic Systems.”

Frederick Weston, Blue Bathroom Blues 1 (detail), Mixed media collage, 11” x 8.5”, 1999. The Scarab Club.

Corktown resident Jon Strand, a meticulous painter with work in the Detroit Institute of Arts’ collection, calls the exhibition a seismic event for the local queer community and its visibility. “This is like a declaration that we’re real and we make beautiful art,” he said. “We weren’t trying to promote or indoctrinate. It’s just about great creativity coming from all kinds of sources.”

One of those sources is Strand himself, who has work in this particular show at both Collected Detroit and Detroit Artists Market. The latter includes “The Flaming Pearl of Infinite Wisdom, A Silvery Moon, and Seven Hidden Dragons,” which typifies the artist’s fascination with oddly whimsical, otherworldly canvases created by means of a back-breaking form of pointillism.

Jon Strand, The Flaming Pearl of Infinite Wisdom, A Silvery Moon, and Seven Hidden Dragons, Ink on canvas, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

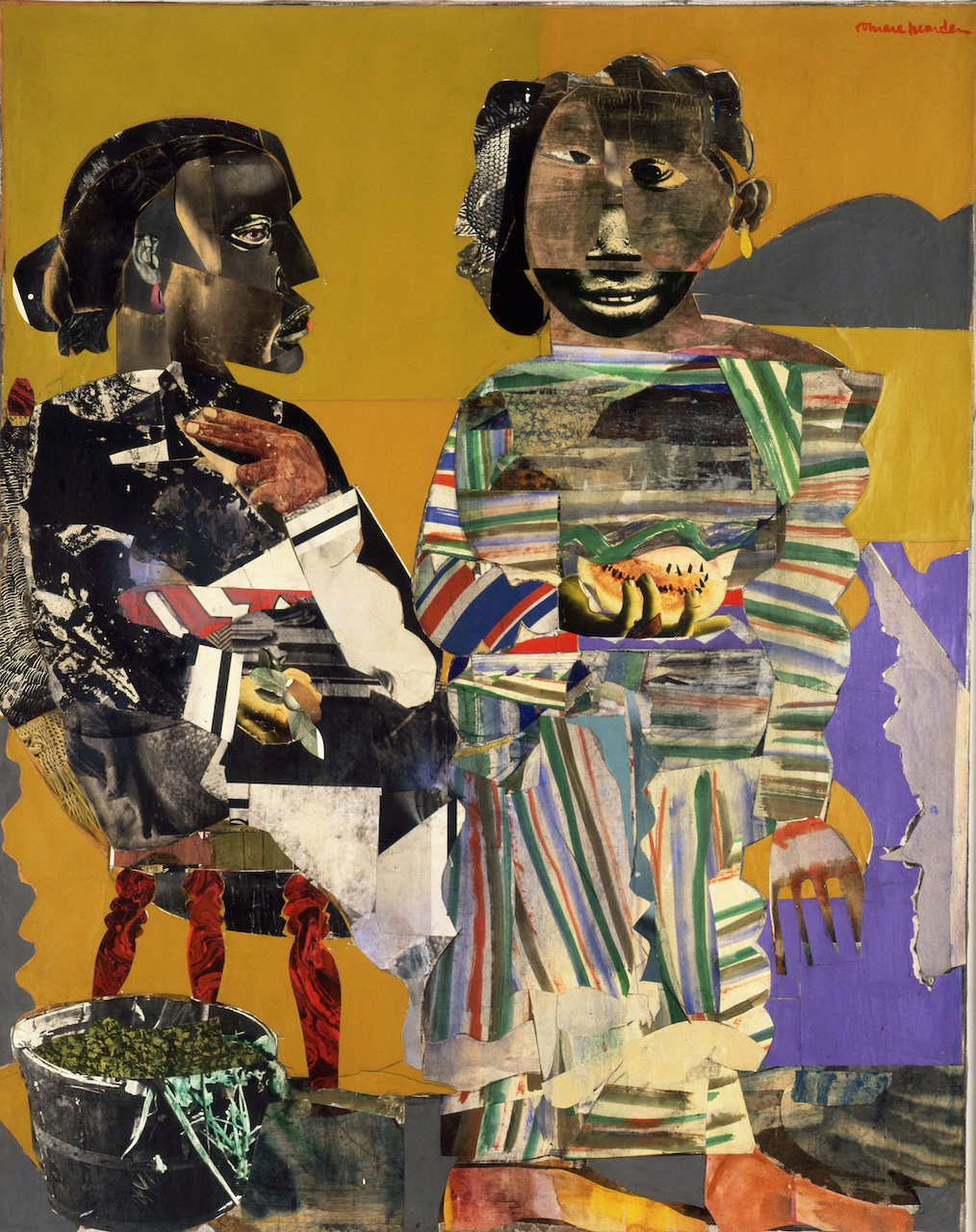

Much of the work throughout MRQD is recent, but Burton also reached back far for some particularly arresting visuals as far away as New York City. Among the most striking, for reasons that are a little hard to decipher, is Marcus Leatherdale’s black-and-white portrait of Sam Wagstaff from 1981, 10 years after he left his curatorial position at the DIA in some disgrace. (For a contemporary art project, Wagstaff in his last year at the museum drove a bulldozer across the museum’s pristine north lawn dragging a 35-ton monolith, “Dragged Mass Displacement” by Michael Heiser, that gouged its own trench and sent the DIA’s board of directors into conniptions.)

Marcus Leatherdale, Sam Wagstaff, Archival pigment print, 22” x 22”, 1981. The Scarab Club.

Leatherdale, a photographer of New York’s demimonde who died in May, gives us a sharply observed portrait of the curator and photography collector at 60, with chiseled good looks and a skeptical gaze some eight years before his lover, Robert Mapplethorp, would die of AIDS.

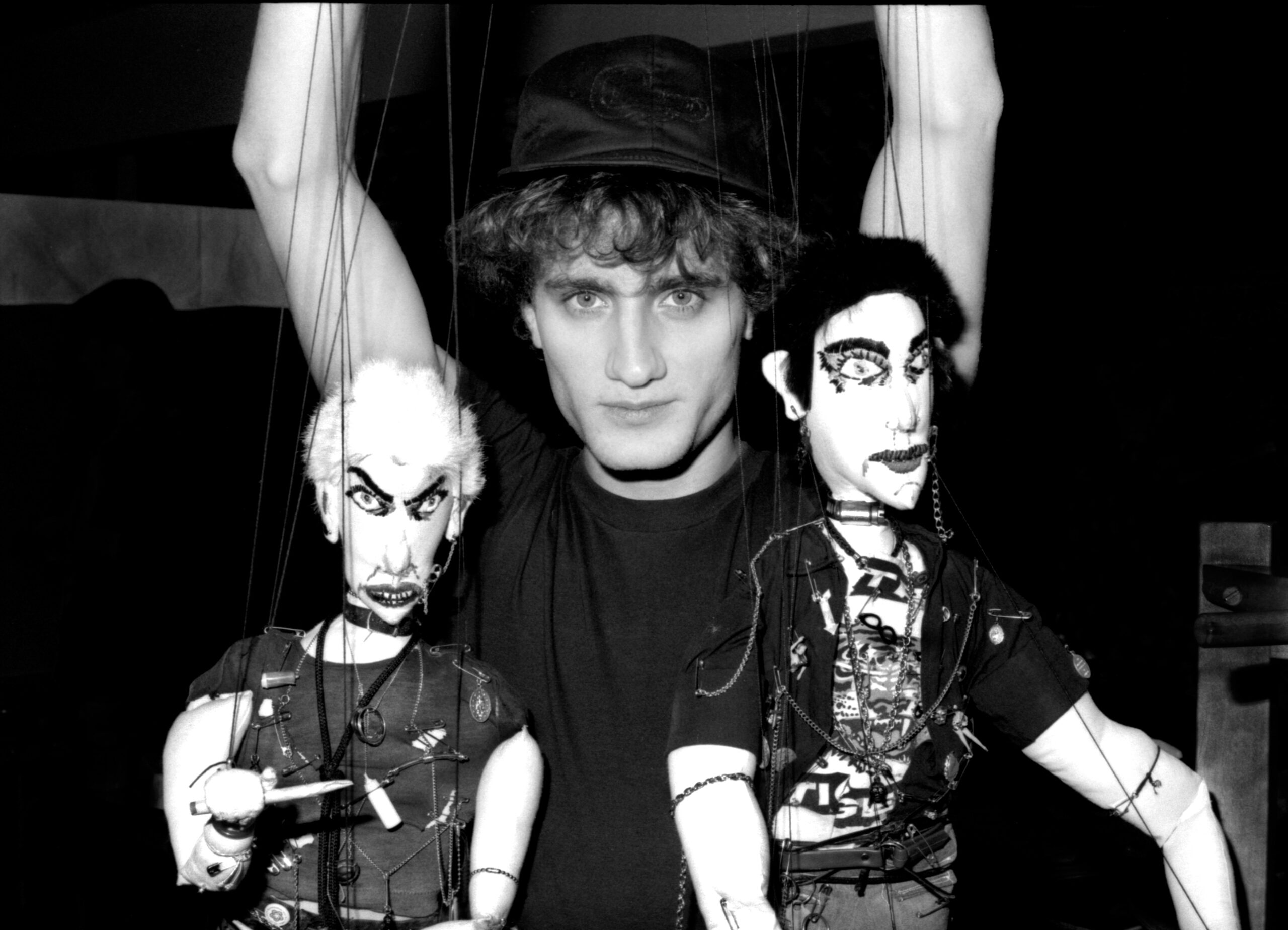

Another striking image from the now-distant past is Detroiter Katy Hait’s “Marc Mannino, Detroit,” with the tousle-haired artist holding up what look like two punk marionettes. The juxtaposition of the puppets’ menace and Mannino’s youthful gaze, apprehensive but as yet unbruised by life, is a knockout.

Katy Hait, Marc Mannino, Detroit, Archival pigment print, 19” x 13”, 1977. The Scarab Club.

Other participating venues hosting “Mighty Real / Queer Detroit” include Affirmations, Cass Café, the College for Creative Studies Center Galleries, Galerie Camille, M Contemporary Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Design Detroit, N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art, Norwest Gallery, Oloman Café & Gallery, Playground Detroit and Public Pool.

In breadth, scope and daring, MRQD will be remembered as a landmark in Detroit’s artistic and gay history. In Flannery-Erickson’s words, “It was a monumental undertaking that involved so many people. At the end of the day, it’s a beautiful salute to community.”

Like all curators, Burton hopes for lasting impact. “It’s a community defining ourselves,” he said. “When you think about, it was just over 50 years ago that there was the Stonewall uprising (in Manhattan). I just think there’s a lot of work still to be done. This exhibition is a beginning here, and we wanted to do it big and we wanted to make sure it got the right attention. The only way to do that was to not just do one gallery.”

“Mighty Real / Queer Detroit: Remembrance of Things Present” will be up at Detroit’s Scarab Club through July 9. The other 16 exhibition spaces will take the show down on June 30.