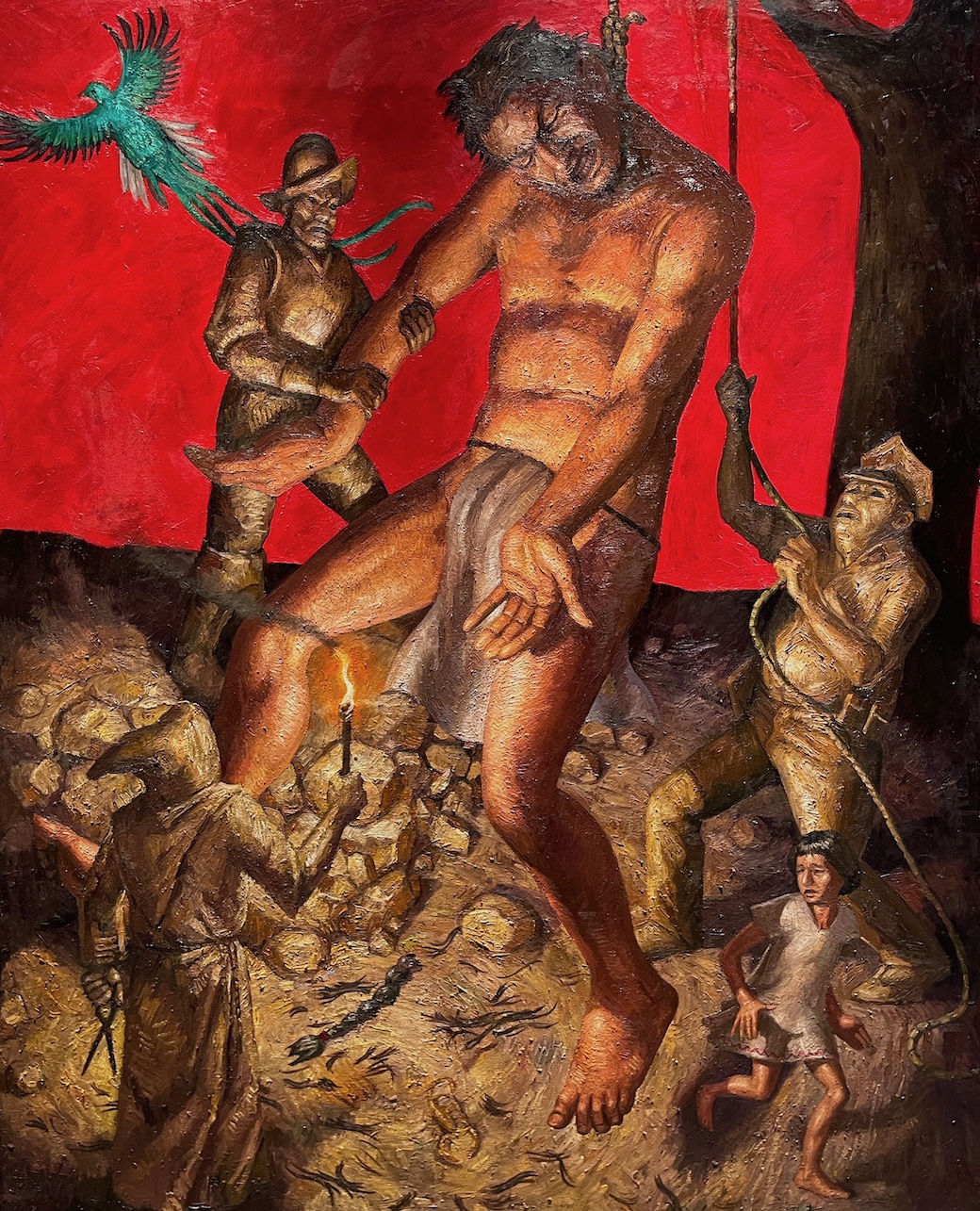

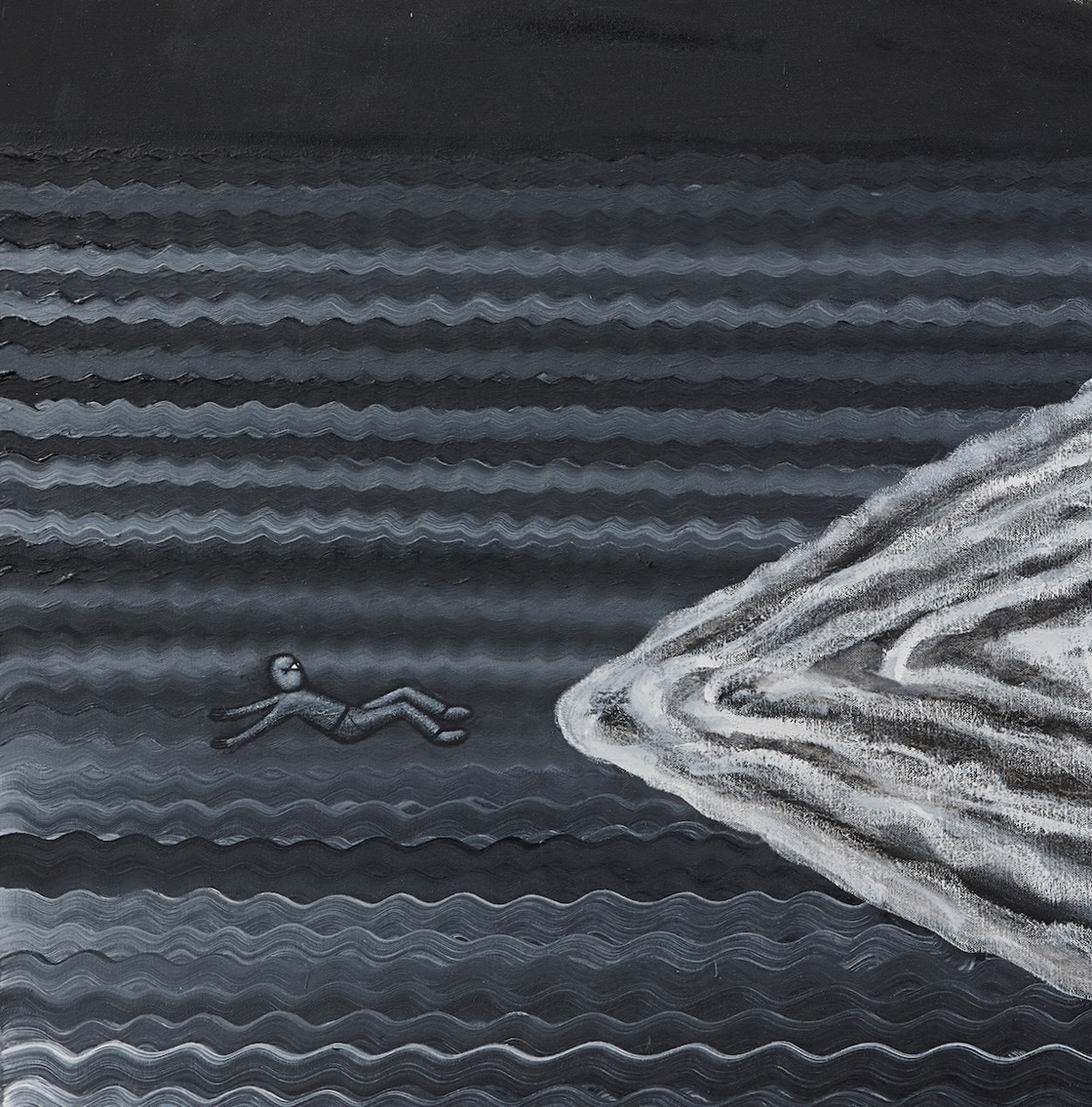

Paint Creek Center for the Arts, Installation image Courtesy of DAR

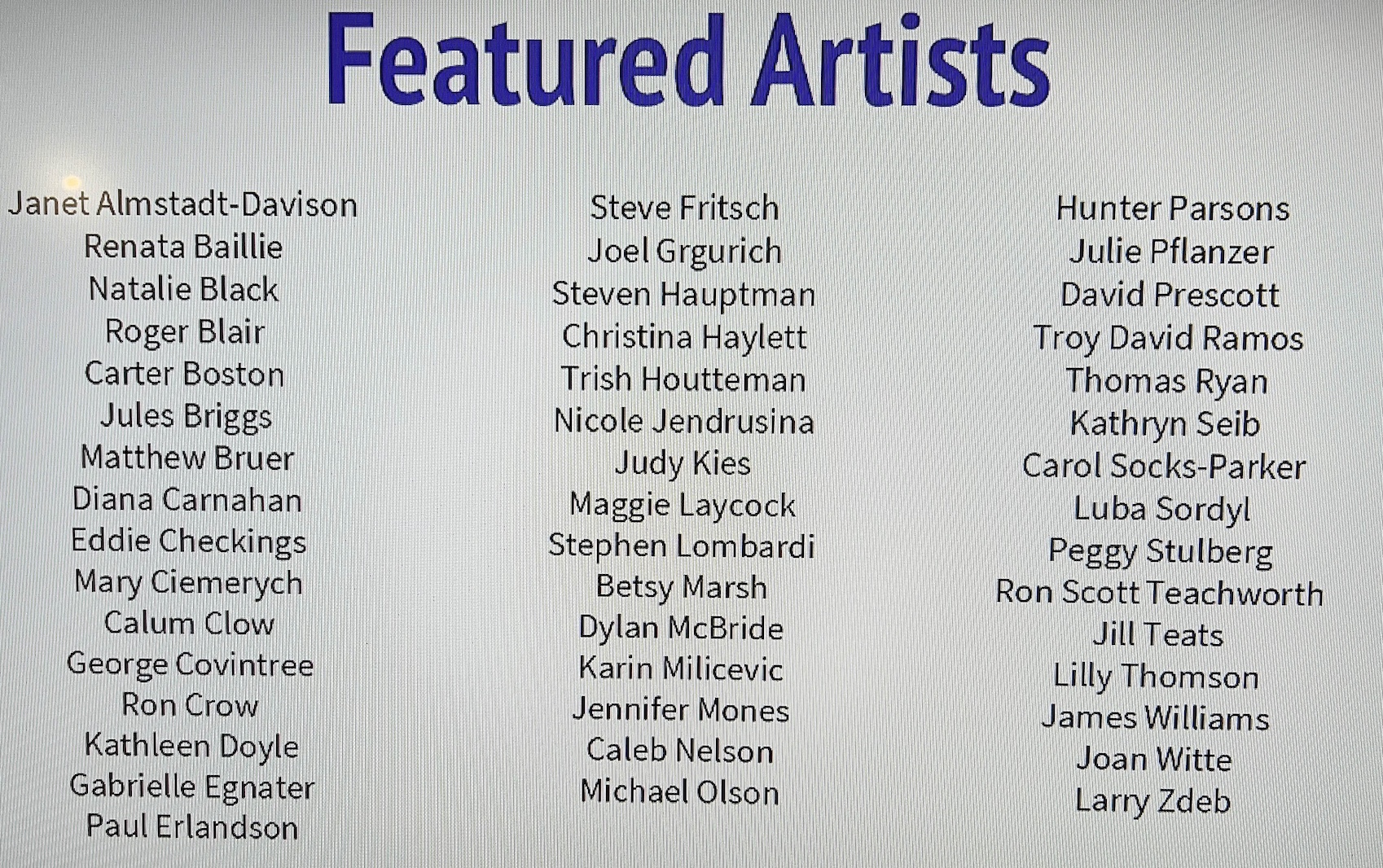

The Paint Creek Center for the Arts opened its 2025 season on March 28th, 2025. Two hundred twenty viewers came to the opening to see art by forty-five artists whose work was accepted into an exhibition titled The Reality Show.

In a statement by Julia Felts, gallery director, “In a time when reality television, social media and spam can shape our perceptions of everyday life, how do we know what is real? Whether you’re capturing your own reality through life’ pleasures, struggles, and monotonies, interpreting the reality of someone else or exposing pop culture’s simulated perfection, we invited artists to submit their artwork showcasing and defining what reality means in the modern world.”

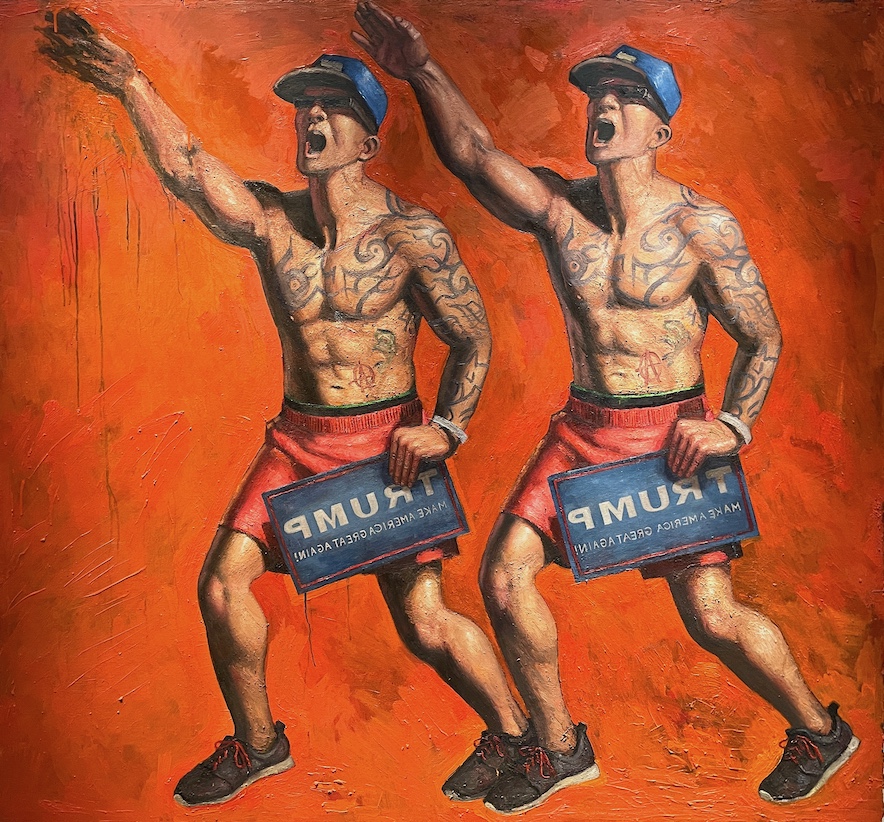

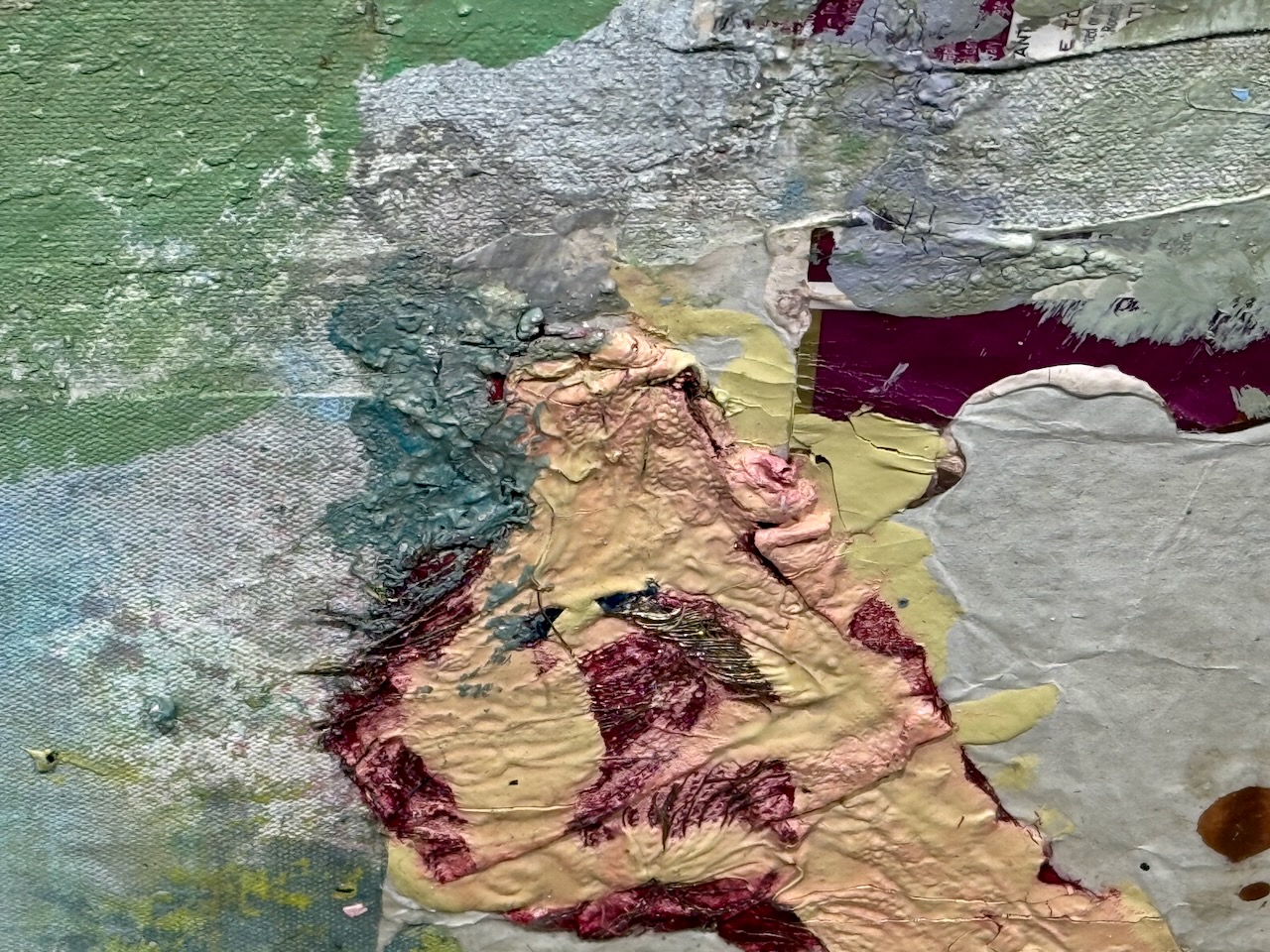

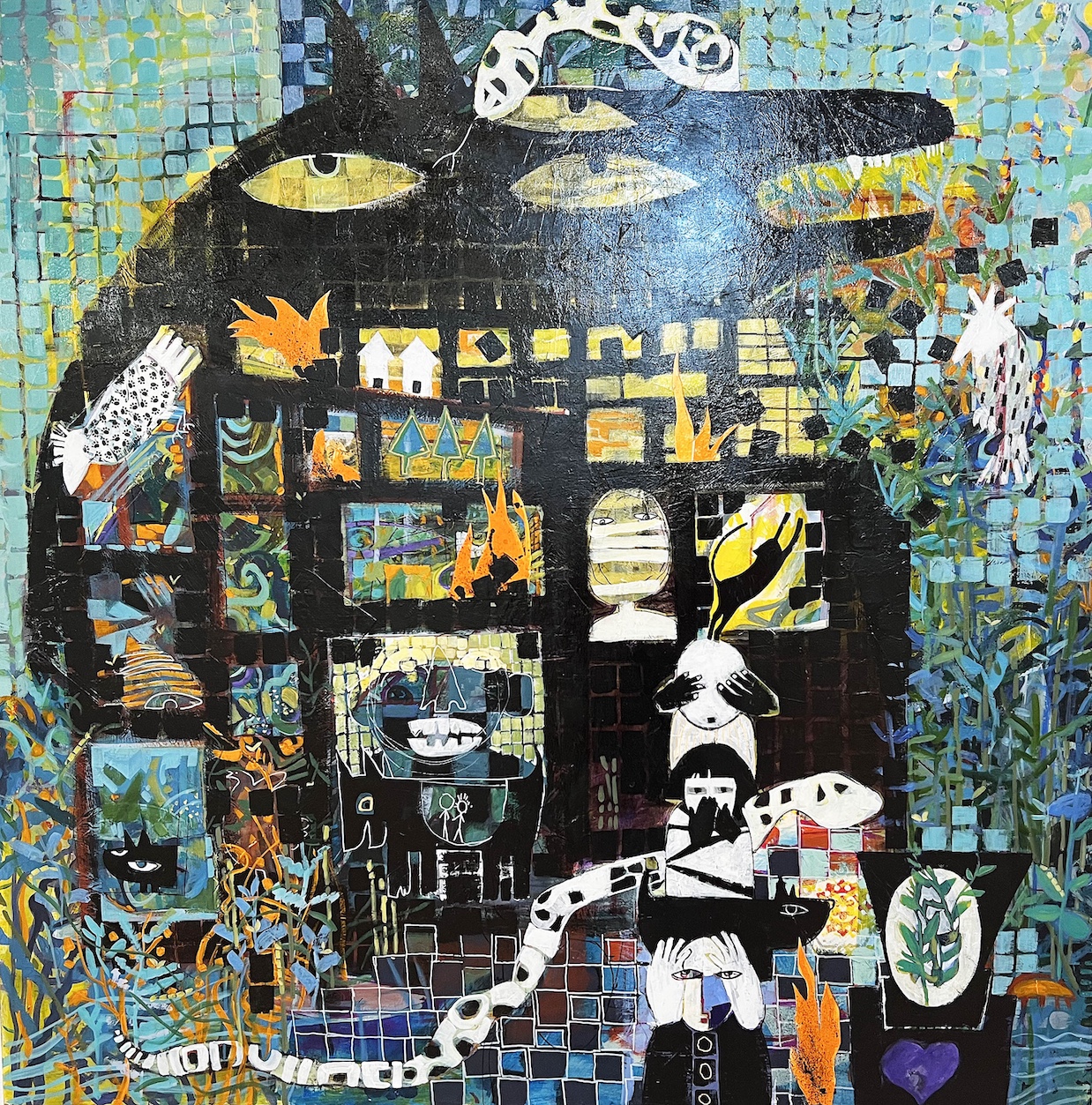

Christine Heylett, Nature of Things, 48×48″, Board, Paint, Paper Courtesy of DAR

Awarded Best in Show, artist Christina Haylett’s large collage titled The Nature of Things, “48 x 48” creates a grid of symbols set over a large black imaginary animal. A montage of small squares provides the adhesive in this surreal fantasy of imaginary reptiles and objects. She says, “Climate change is part of our daily concerns and every day there are programs in our media about all of this.”

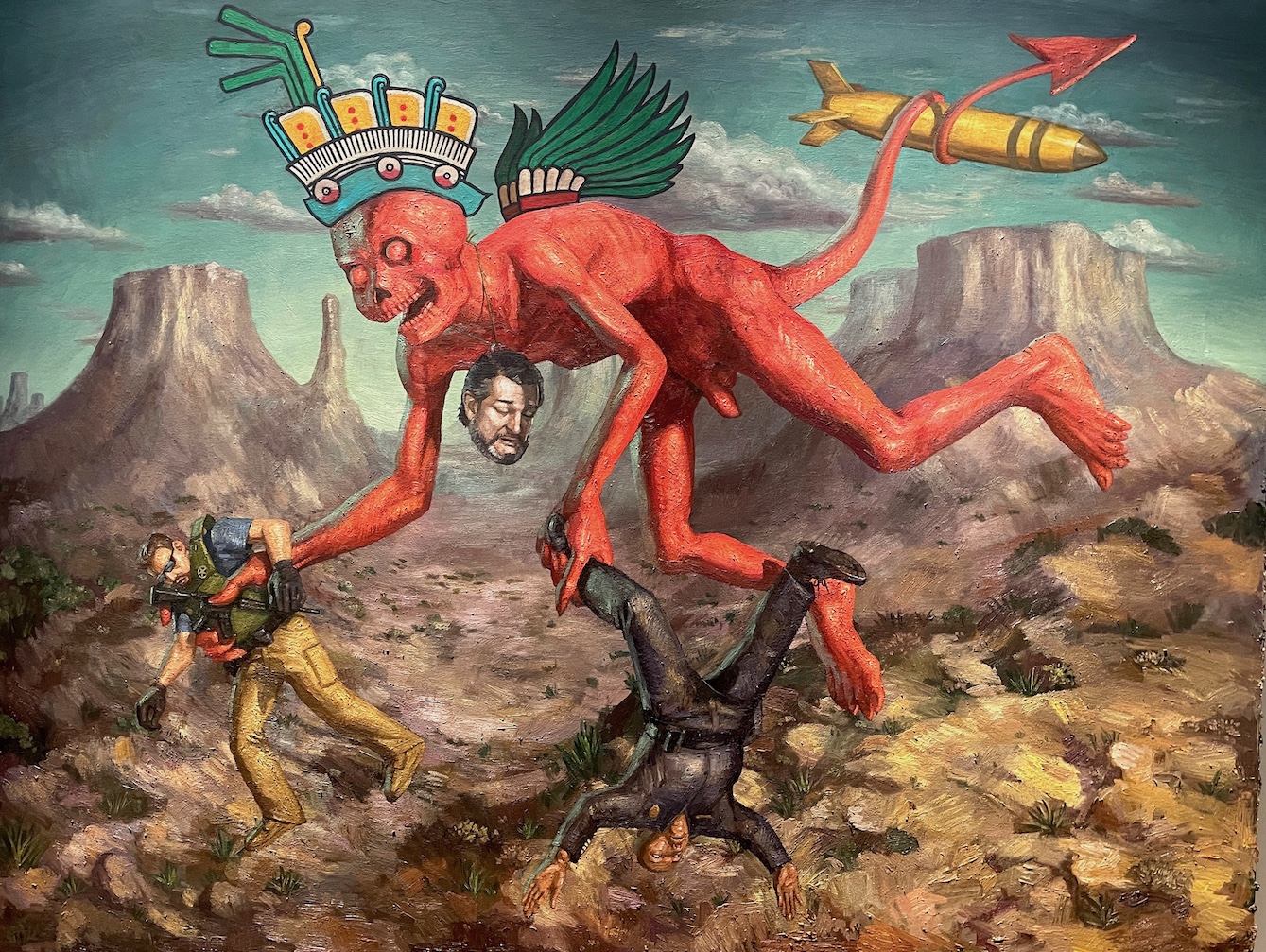

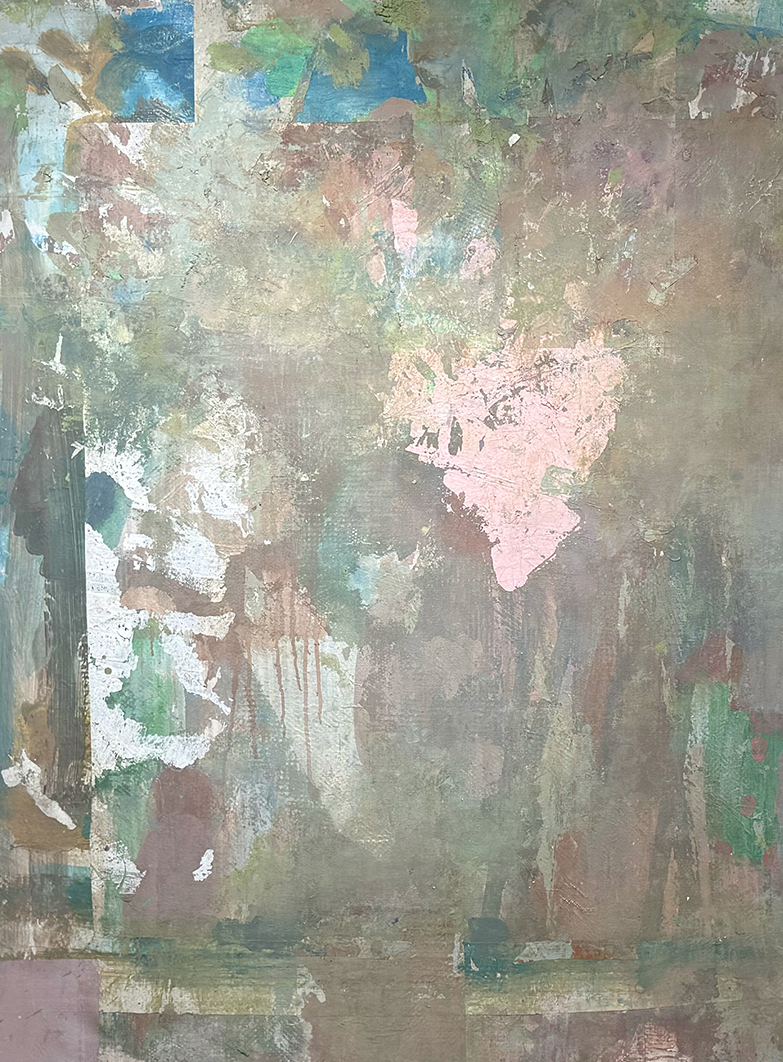

Calum Clow, Hindsight and 2020, 30×28″ Cardboard on Wooden Panel, Courtesy of DAR

This nearly square figure painting was created using Oil, Mixed Media, and Cardboard on a wood panel illustrates a female mom seated at the laundromat during the Covid-19 virus pandemic using a ¾ profile looking off to the left. In his notes the artist provides the audience with a story.

“In the Summer of 2020, our laundry machine broke. So we donned our masks and cleaned our clothes at the laundromat. The portrait is from a photo I took of my mother, watching another day of breaking news stories on multiple televisions while doing laundry. This painting documents our reality within this moment of a global pandemic, a civil rights movement, and a tumultuous political landscape. It questions how the perspective of our own reality is changed through reflecting upon the realities of the world around us.”

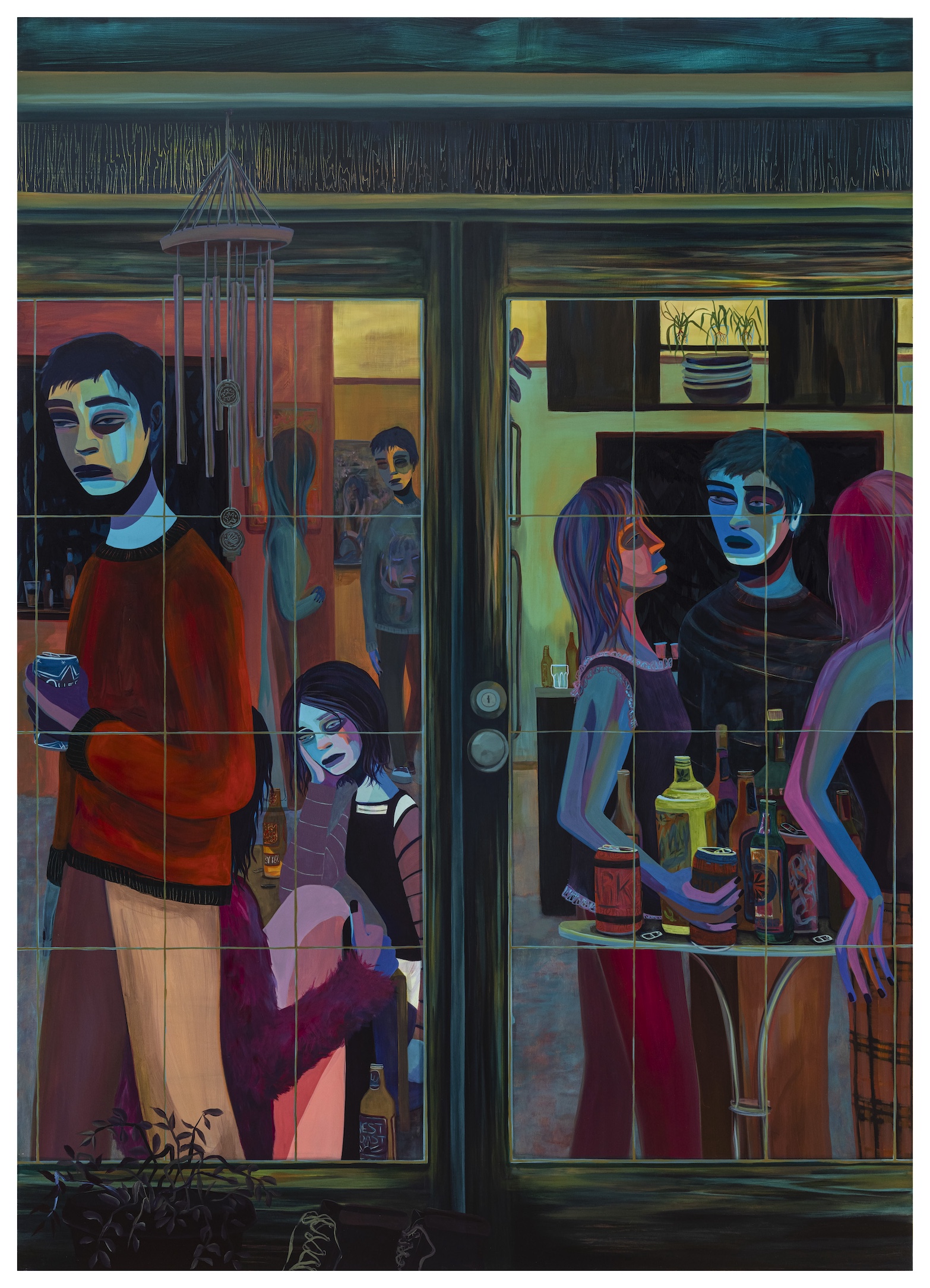

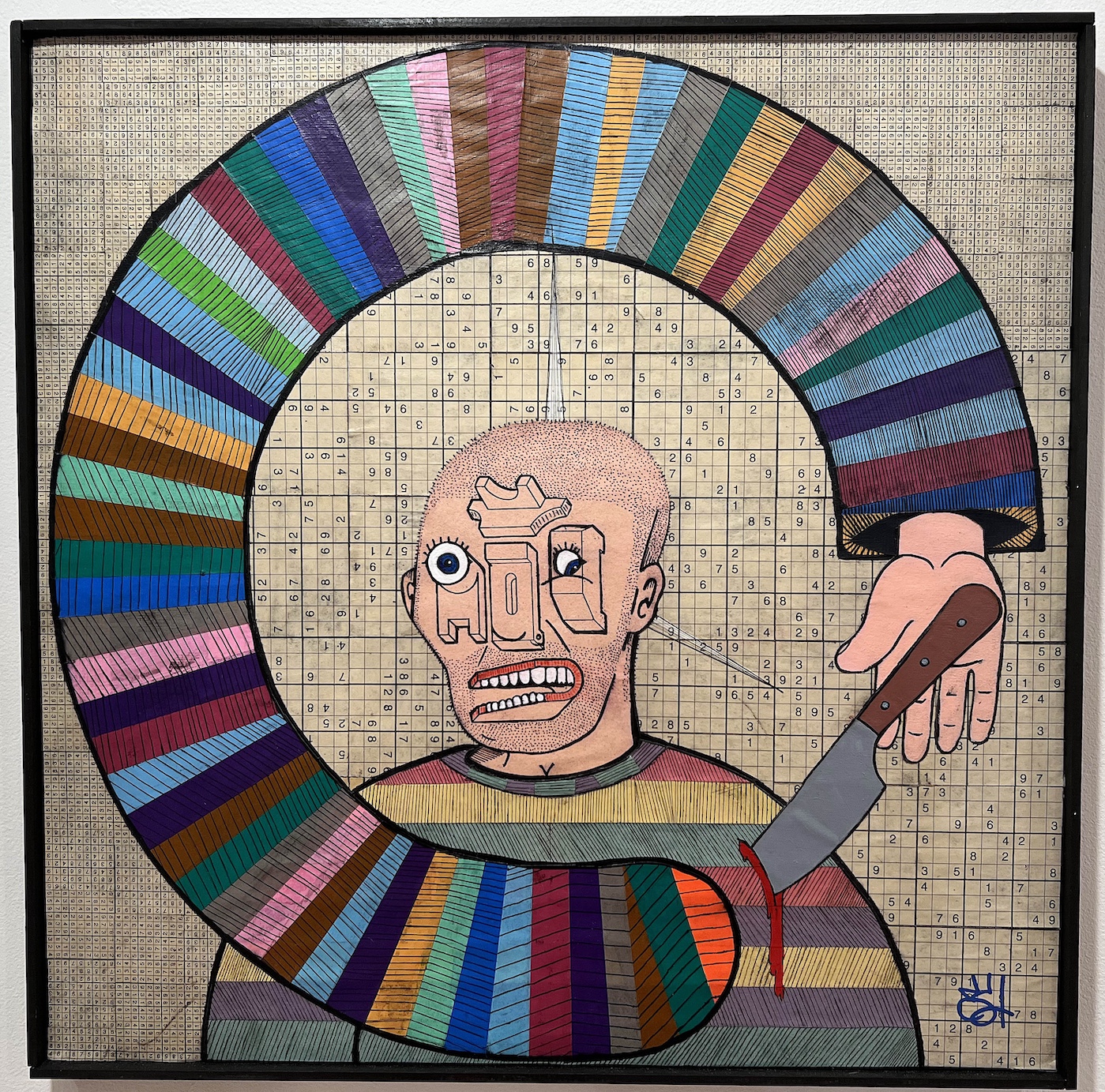

Eddie Checkings, Backstabber, 24×24″ Collage, Acrylic, on Wood, Courtesy of DAR

Eddie Checkings is an artist mostly recognized on Instagram with work that is more illustrative than, let’s say, traditional forms of painting. Backstabber’s square composition is a collage on a wood panel that might reflect a story. The surreal figure is set on a field of numbers that flattens out the facial expression, where the emphasis could be more dependent on an event. In looking at the artist’s other work, the range of subjects varies greatly, relying on line, color, and composition.

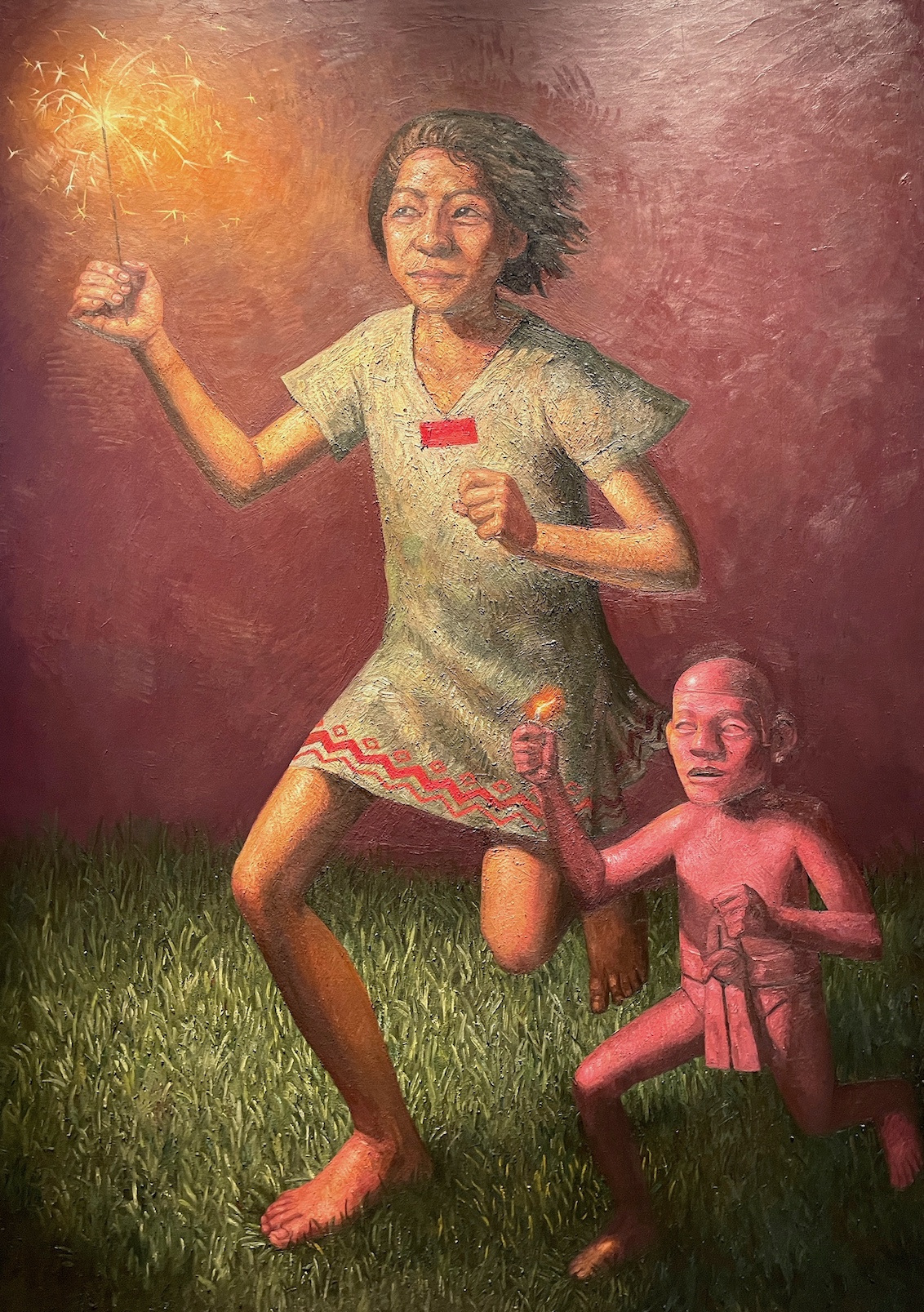

Installation image, Paint Creek Center for the Arts, Courtesy of DAR

The title of the PCCA exhibition, The Reality Show, provides a platform to call on artists to provide a tremendous range in personal subjects and experiences. The expressions of art in the show widely vary to include paintings, sculptures, photographs, drawings, and multimedia works of art.

Paint Creek Center for the Arts (PCCA) is a nonprofit art center in downtown Rochester dedicated to promoting the arts and artistic excellence through various cultural programs, including exhibitions, studio art classes, outreach programs, community involvement projects, and the Art & Apples Festival. PCCA programs reach many different segments of the region and serve as tools for community enhancement and economic development by improving quality of life and drawing visitors to the area. PCCA is an important cultural resource and destination and a vital presence in greater Rochester’s diverse and growing business and residential community. https://pccart.org 248.651.4110