“Good Grief” by Valerie Mann is on exhibition at the Bloomfield Birmingham Art Center

Spidery wire grids that cast shadows on the gallery walls, subtly worn fabrics, discarded electrical cords and occasional flashing lights populate a solo exhibition of recent work by Michigan artist Valerie Mann. “Good Grief,” now at the Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center until June 1, shows this mid-career creative, once again, to be a master of her materials. An inveterate collector of scavenged bits and pieces, Mann finds creative promise in unloved discards that speak of a previous life and re-purposes them to tell a story of loss, recovery, and resilience.

Unlike many artists who are newly enamored of upcycling in their art practice, Mann’s childhood on an Indiana farm birthed her make-and-mend mentality and honed her appreciation for the expressive potential of discarded objects and commonly available commodities. As she points out, “I’ve worked this way long before it was cool.” Her virtuosic use of reclaimed oddments perfectly illustrates a moment when contemporary art trends catch up with the long-held vision of an individual artist.

Valerie Mann, Safety Net, 2021, reclaimed fabric and wire, thread, steel, 39” x 44” x 6,” All images by K.A. Letts

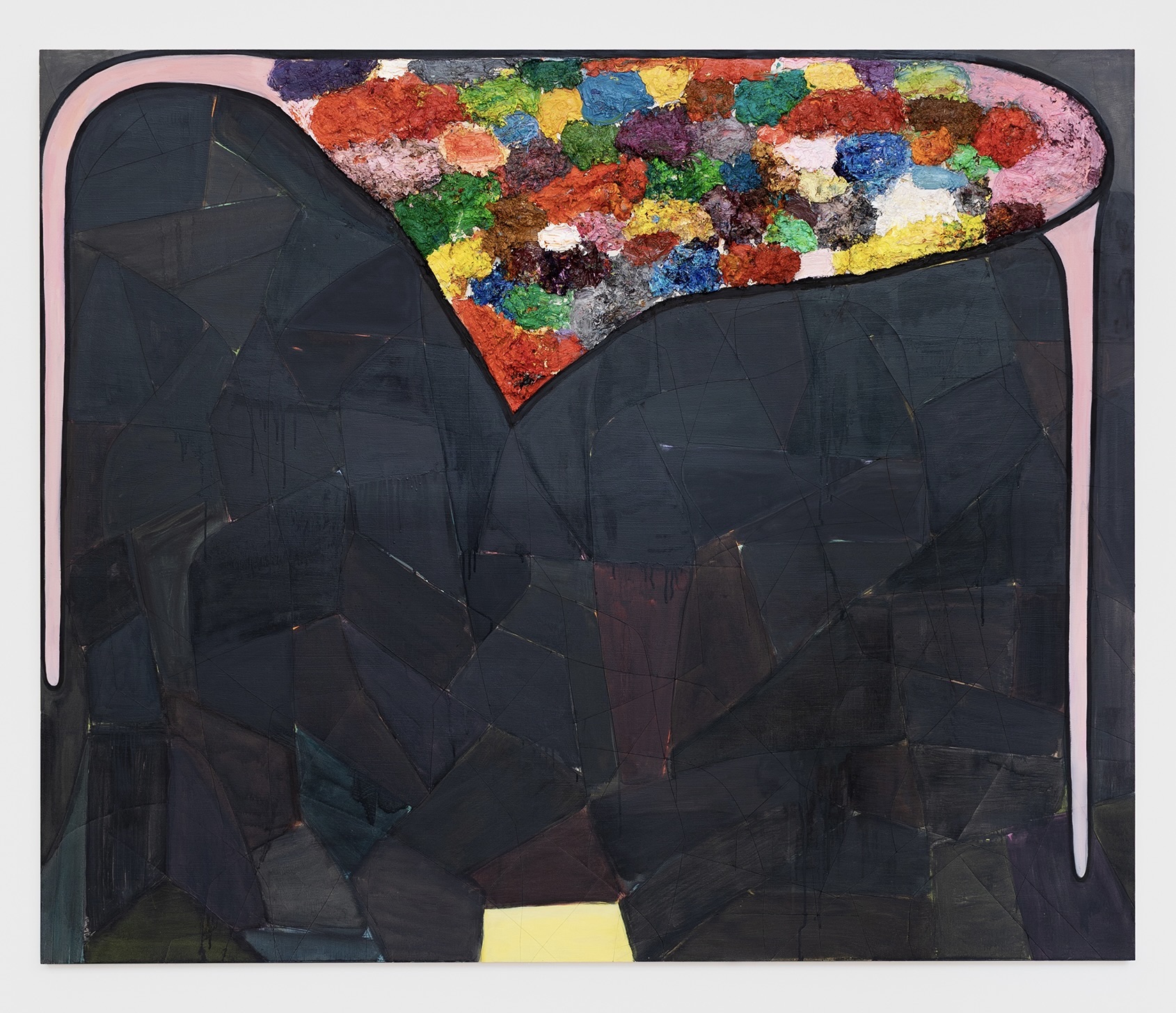

In formal terms, the best works in “Good Grief” are four large wall assemblages made of various common materials arranged in loose grids. Each beautifully crafted, tapestry-adjacent artwork has its own visual vocabulary and tells an emotive story that transcends mere narrative. Each invites us to a slightly different meditative state, weaving the familiar with the fantastical.

The ethereal Safety Net evokes feelings of weightless consciousness at the boundary of sleep and wakefulness. Carefully sewn, empty pockets of reclaimed cotton tulle in subtle tones of pink and green are reminiscent of small nets used in home aquariums, and we feel ourselves slipping through them to the cloud shadows beyond. In this liminal space, the poetic and the practical are perfectly balanced.

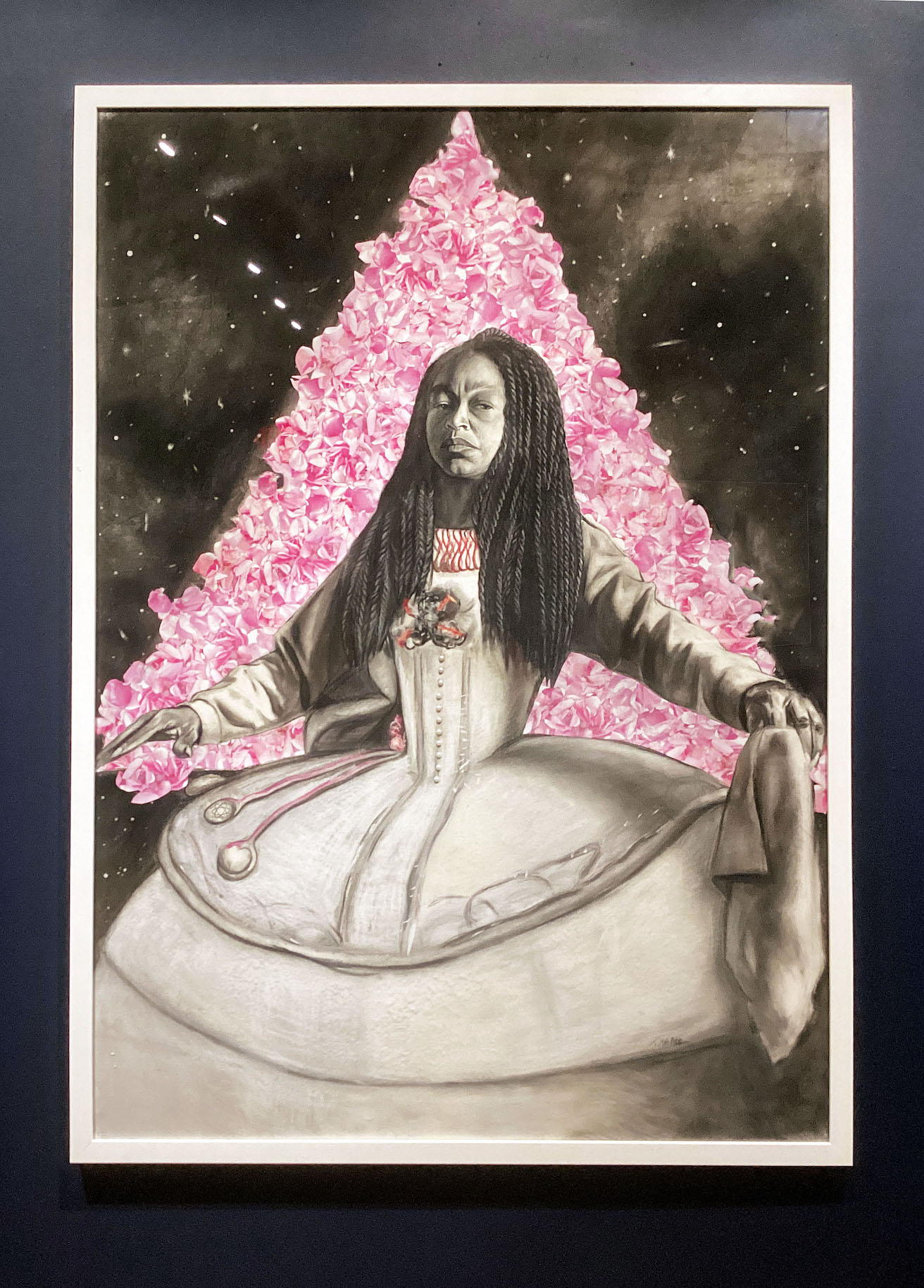

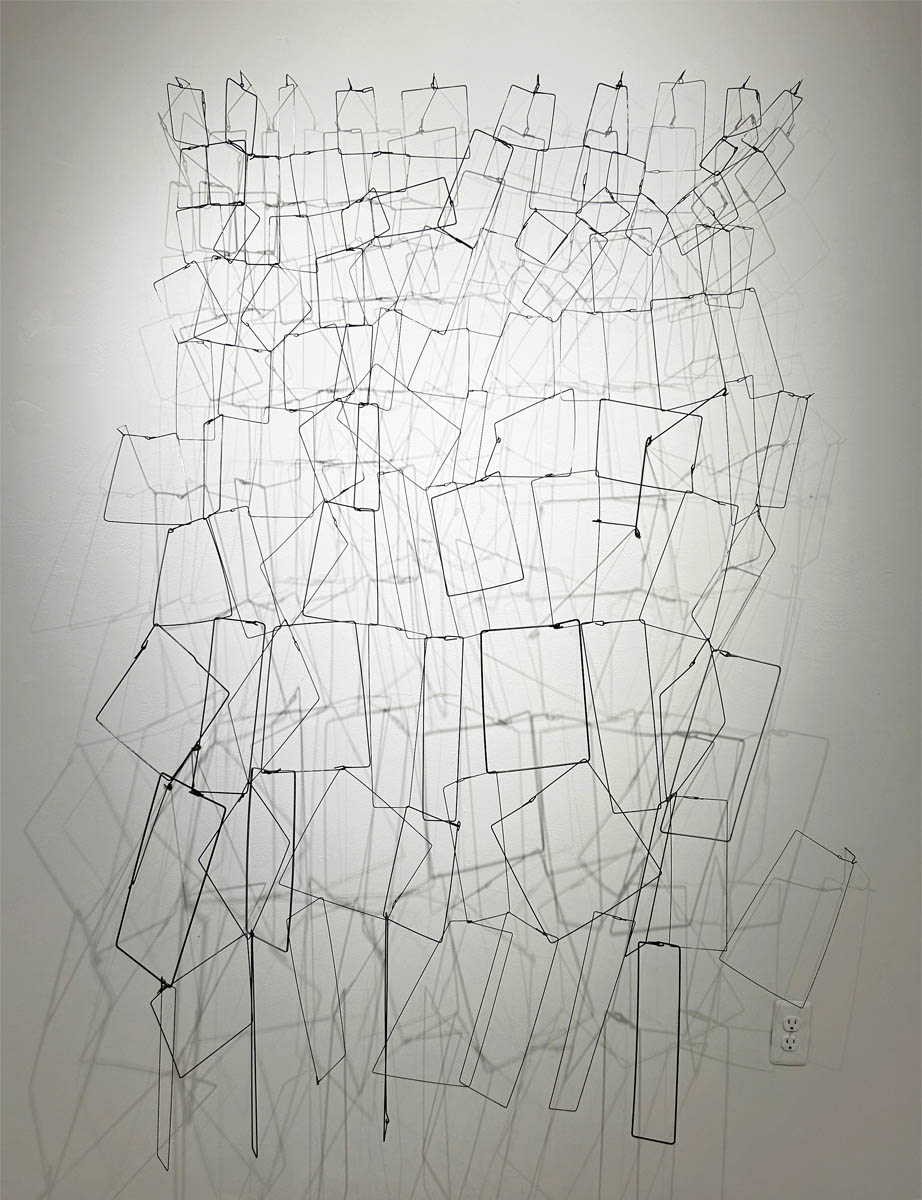

Valerie Mann, Spill, 2023, utility wire, 73” x 60” x 5”

In Spill, Mann has chosen a relatively anonymous base component—workaday galvanized steel utility wire—in order to let the rectangular forms, interconnected and repeated in varying sizes, dominate the composition. We can almost hear the silvery sound of pins or nails or paper clips dropping as she catches the moment in mid-fall. The relative featurelessness of the wire shortens the perceptual distance between the physical forms and the shadows on the wall behind them, setting up a visual fugue–the shape introduced in substance and repeated in shadow. The result is a satisfying contrapuntal composition.

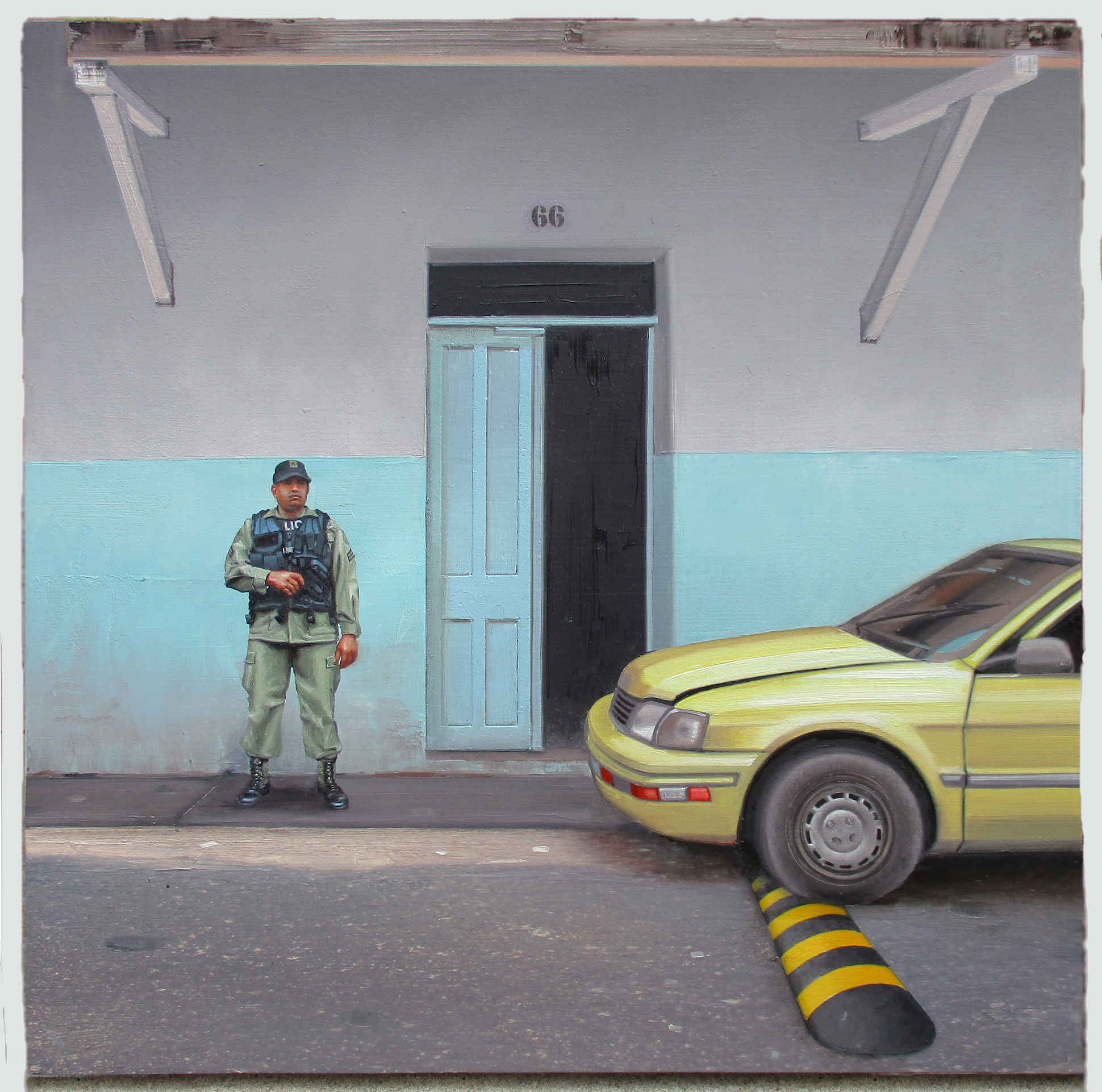

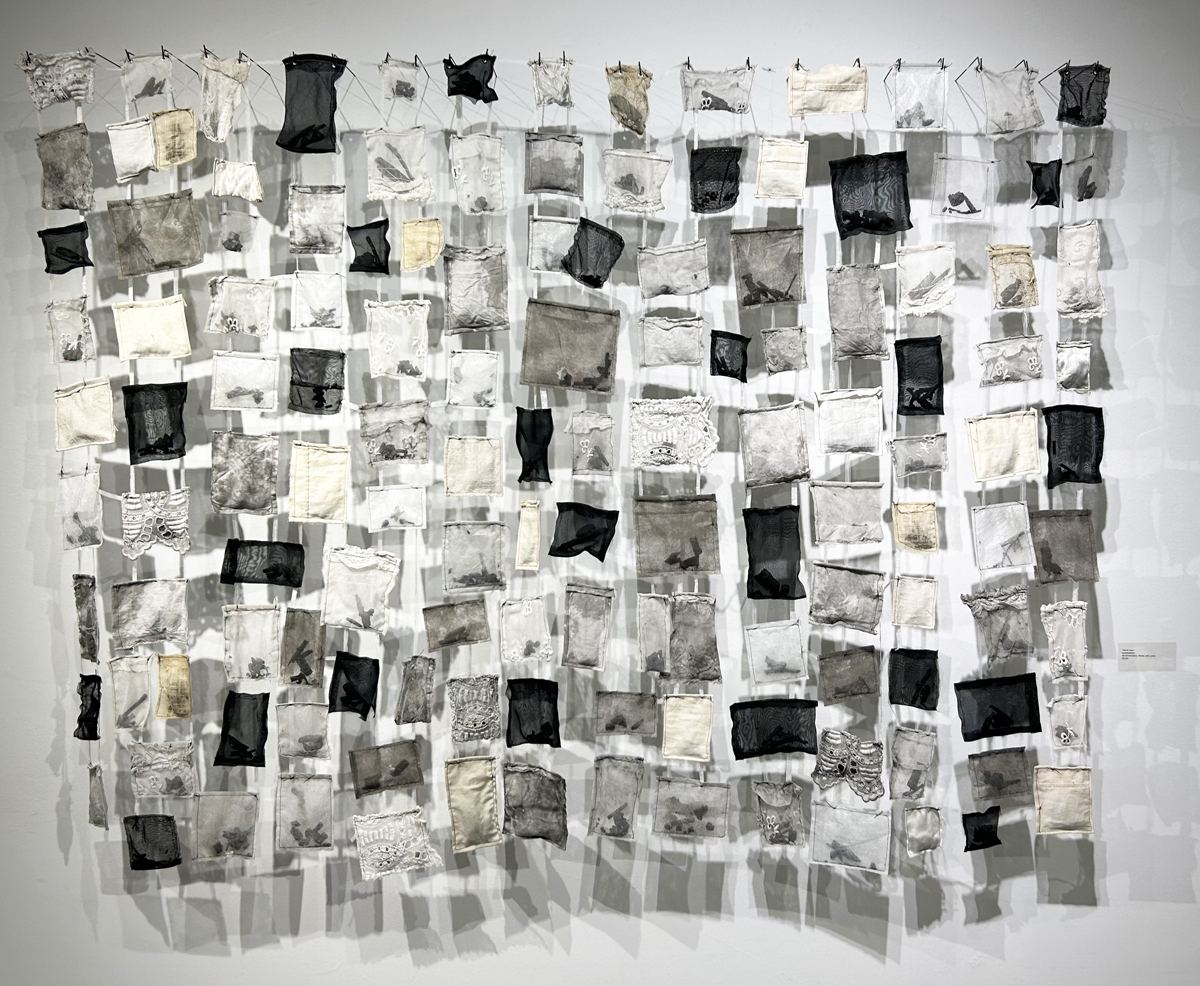

The artwork that most directly addresses the exhibition’s theme of loss is Lamentations, a recent winner of the BBAC President’s Award. Tiny bits of unrecognizable detritus, charred fragments in small bags of tulle, muslin, and lace, illustrate a state of sorrow felt by the community as well as the individual. It reminds us that grieving is both a collective and a solitary pursuit. The title Lamentations recalls Biblical references to sack cloth and ashes. The emotional contrast between the delicate containers of reclaimed fabric and the raw, burned contents within captures the way in which unspeakable loss is contained within public conventions of mourning.

Valerie Mann, Lamentations, 2022, reclaimed fabric, thread steel, ashes, 49” x 67” x 5″

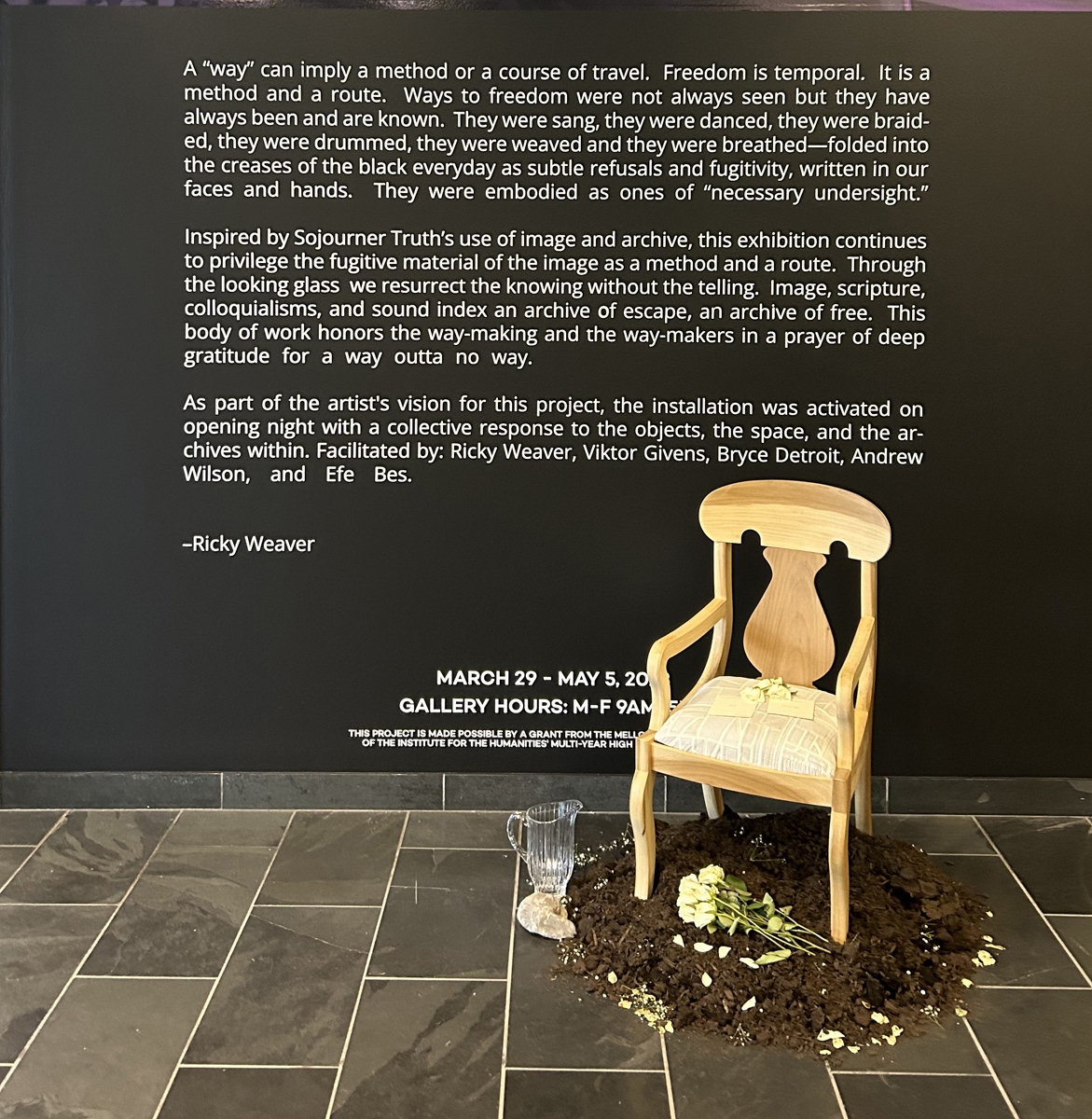

The mood lightens considerably with Correspondence, an exuberant assemblage made from tangled rows of various wires, extension cords and blinking Christmas lights. Who knew that electrical supplies could come in such variety? The composition of the piece, with its more-or-less orderly lines of looping scribbles, suggests a kind of calligraphy, as if the artist is writing us a cheerful holiday letter. The informal, yet intentional, quality of the composition is reminiscent of late paintings by Cy Twombly.

Valerie Mann, Correspondence, 2023, reclaimed wire, cords, lights, and steel, 72” x 68” x 4”

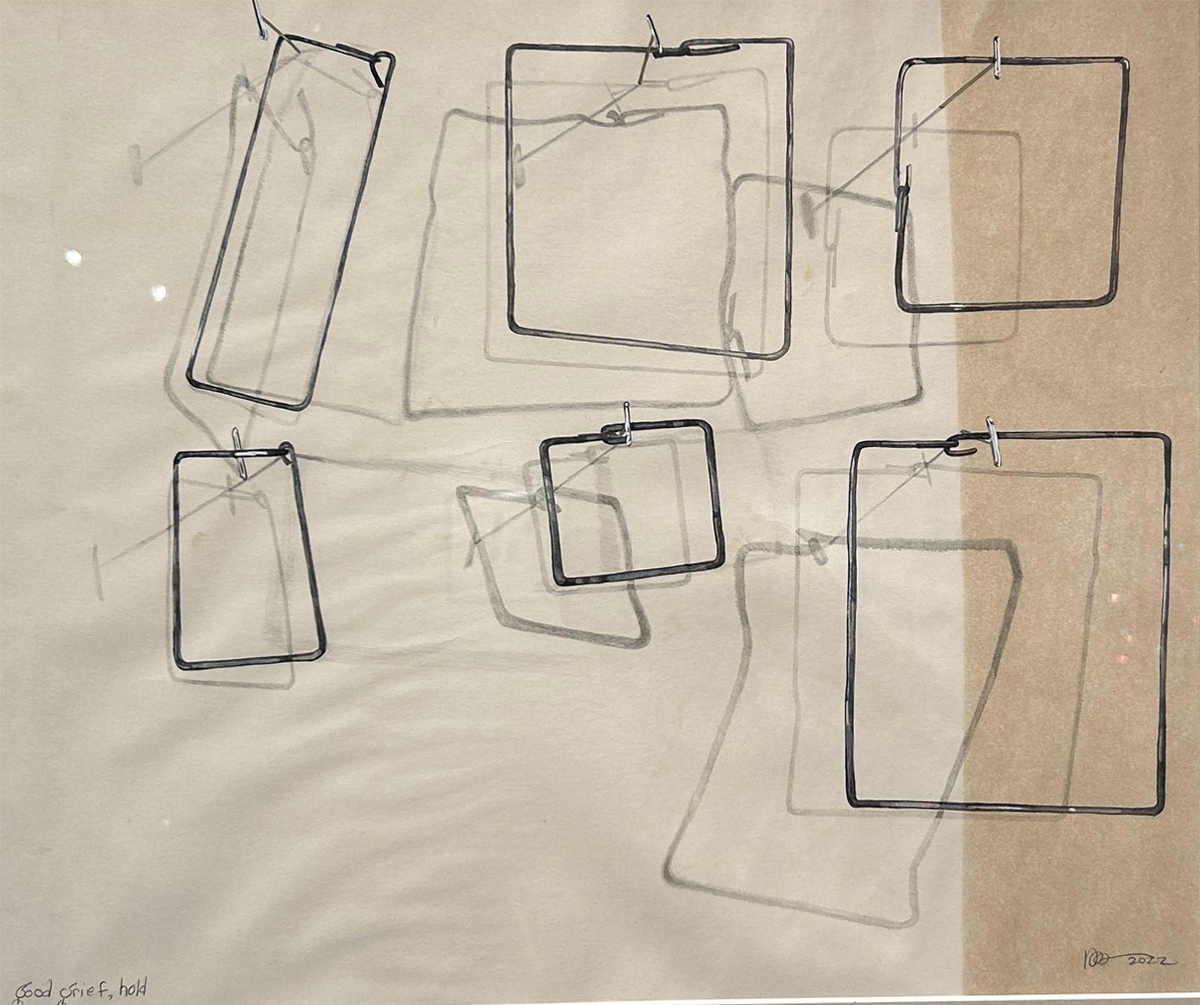

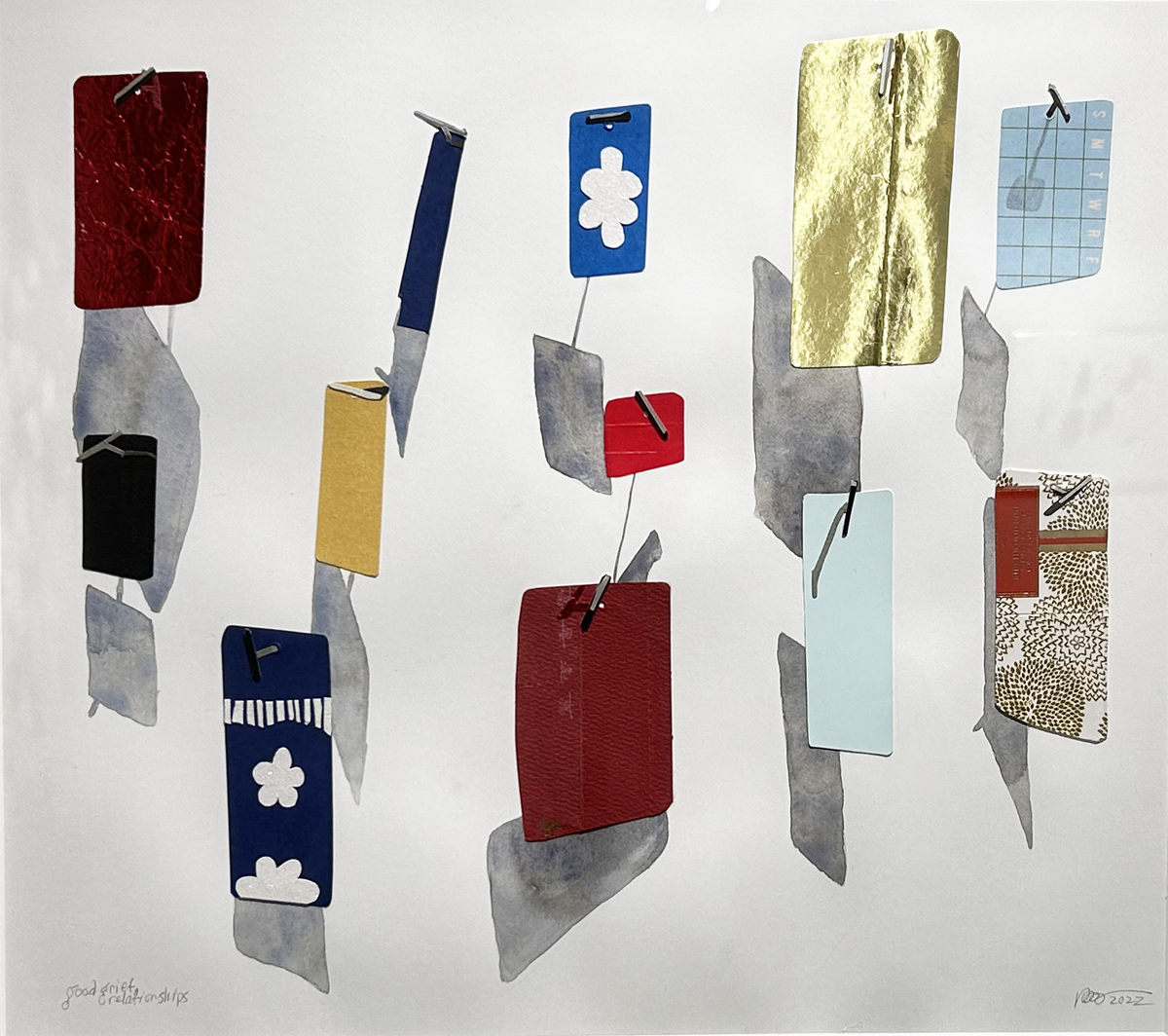

Several small works on paper and wall assemblages round out the offerings in “Good Grief.” Good Grief, Hold; Good Grief, Detach; Connect, and Relate are based on the larger pieces, transpositions of the wall constructions themselves into two-dimensions. Along with Good Grief V and Good Grief VI, these seem less consequential than the larger assemblages. While skillfully executed, the two-dimensional watercolors, collages and drawings lack the visceral energy and textural interest of the three-dimensional work. Several smaller wall-mounted constructions, Uncontained, Good Grief, Connect and Compartmentalize embody the feelings of detachment and isolation with which we can all identify post-pandemic.

Valerie Mann, Good Grief, Hold, 2022, watercolor, gouache, graphite, 16” x 20,”

The artworks in “Good Grief,” many of which Mann created during her residency in June of 2022 at the Glen Arbor Art Center in Leelanau County, Michigan, address emotions that have been very much front and center in our shared consciousness since COVID-19’s assault on our complacency. Mann describes her creative motivation: The ideas I’ve been thinking about for the last few years are grief; how we individually, collectively, and communally experience grief; how we process grief and maintain some of our wholenesses or become more whole; how we learn about ourselves and our connections to the universal experience of grief.

Valerie Mann, Good Grief, Connect, 2022, found objects, linen thread, 24” x 26” x 2”

Our confidence has been shaken. More sensitive to dislocations in the community than most, Mann possesses the formal means to speak for all of us about our collective loss. Through the artworks in “Good Grief,” she has performed a kind of exorcism and a ritual of remembrance which we can all share.

Valerie Mann, Good Grief, Relationships,2022, watercolor, collage, 16” x 20,”

Valerie Mann has been making, exhibiting, and selling her work in the U.S. and abroad for over 30 years. In 1989, she earned a BFA in painting from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and in 1991 was awarded an MFA in sculpture from Michigan State University.