Dodge and Burn (Visible Storage) Stephanie Syjuco, Dodge and Burn (Visible Storage), 2019. Wooden platform, digital photos and printed vinyl on lasercut wood, chroma key fabric, printed backdrops, seamless paper, artificial plants, mixed media. Overall 20 x 17 x 8 feet. Photo: Dusty Kessler. Courtesy of the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco, and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York.

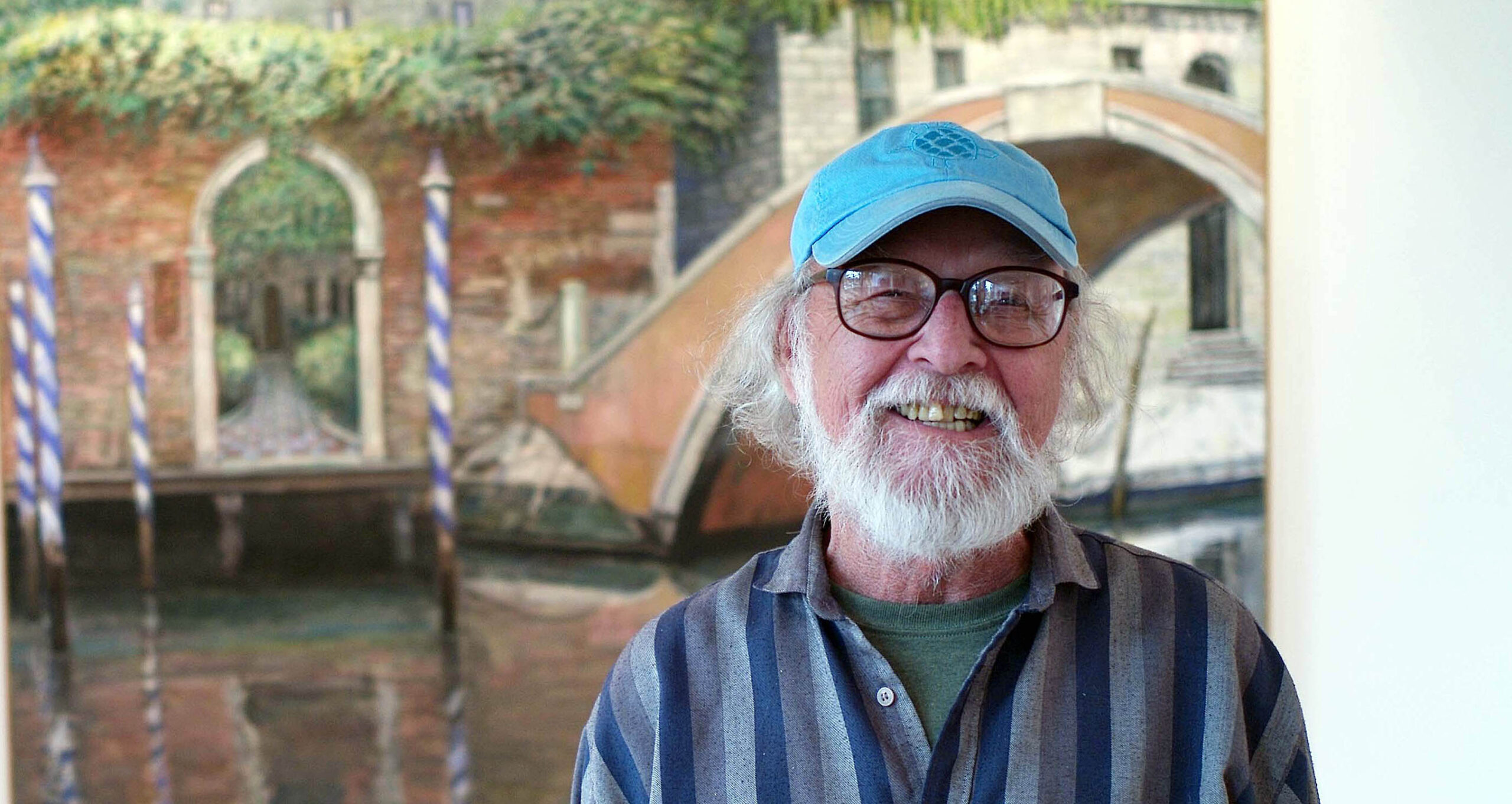

While I chatted with Rachel Winter (assistant curator at the MSU Broad Art Museum) about the artistic practice of Stephanie Syjuco, Winter described her as a “force of nature,” and given her many accomplishments, it’s easy to see why. Syjuco’s work has been displayed at the MoMA, the Whitney, and the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, and her awards include a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship. Recently, she was featured on the PBS series Art21. Born in the Philippines, Syjuco has spent most of her life in the United States, and currently teaches at the University of California, Berkeley. Using America’s colonization of the Philippines as a frequent reference point, her archival and research-based artistic practice addresses the ways photographs and objects can be used to construct skewed narratives.

Through July 23, the Broad presents the exhibition Blind Spot: Stephanie Syjuco, a collection of Syjuco’s work which traverses across photography, sculpture, craft-based media, and installation. This is a diverse body of work with a focused intent, addressing the ways individuals from the Philippines were represented in America during the years of American occupation (1898-1946). America’s history in the region is not given much attention in our history books, and is a “blind spot” for many of us. But these works also speak to colonialism and representation in a broader, more generalized sense.

Syjuco frequently uses chromakey green in her works, a reference to the green-screen used in digital video post-production. And the grey and white checkered pattern she often uses is a reference to the transparency background in Photoshop which fills the negative space in an image after something has been deleted. These allow for both superimposition and erasure, and their prevalence in her work speaks to the omnipresence (particularly in the internet age) of manipulated images and narratives.

Dodge and Burn (Visible Storage) Stephanie Syjuco, Dodge and Burn (Visible Storage), 2019. Wooden platform, digital photos and printed vinyl on lasercut wood, chroma key fabric, printed backdrops, seamless paper, artificial plants, mixed media. Overall 20 x 17 x 8 feet. Photo: Dusty Kessler. Courtesy of the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco, and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York.

The exhibition’s namesake, Blind Spot, is an evocative digital reconstruction of photographs taken during the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. In addition to showcasing new technologies and scientific innovations, the fair also Included what was described at the time as a “human zoo,” featuring more than 1,100 individuals who were trafficked from the Philippines and who, for the duration of the fair, inhabited a Disneyland-style mockup of a village. It was conceived as an educational display, but the exhibit also served to propagate notions about racial inferiority. Photographs of these individuals, taken as they posed in front of backdrops and dioramas suggestive of the South Pacific, helped disseminate these problematic ideas. Blind Spot is a digital intervention for which Syjuco manipulated these images in Photoshop, removing the people and leaving in their trace ghostlike, blurry apparitions. In the 40 images that comprise Blind Spot, all we see are the backgrounds that these individuals were posed in front of, and in removing the people from the photos, Syjuco symbolically liberates them from the ethnographic gaze. Begun in 2019 during a Smithsonian research fellowship, Syjuco completed the project specifically for this exhibition, and afterward it will enter the Broad’s permanent collection.

Blind Spot Stephanie Syjuco, Blind Spot, 2023. Pigmented inkjet prints mounted on aluminum. Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, Michigan State University, purchase, funded by the Nellie M. Loomis Endowment in memory of Martha Jane Loomis, 2022.33

Although the installation Dodge and Burn (Visible Storage) is sculptural, like Blind Spot it also directly addresses photography and representation. The title references the photographic darkroom technique of lightening or darkening certain parts of the image, though Dodge and Burn can certainly be read in more literal ways. The ensemble presents a large stage crammed with images and objects associated with the Philippines. Many of these are cut-outs of stock images (watermarks clearly visible) that are displayed as prop-like objects. The centerpiece of the ensemble are sculptural representations of two women from the late 19th Century, one in traditional Filipinx dress, and one dressed in more Western fashion. It’s an intentionally busy sculptural collage which the artist likens to having too many tabs open on a computer. While the work reminds us of America’s colonial history, contemporary references in the ensemble (emojis, photographic color calibration charts, and MAGA hats) encourage us to think about the extent to which America is still a colonial power (Puerto Rico and Guam remain U.S. territories, after all, an enduring legacy of the 1898 Treaty of Paris). Subtitled “Visible Storage,” the work serves as a critique of how objects in museums have often been used to construct problematic narratives.

Dodge and Burn (Visible Storage) Stephanie Syjuco, Dodge and Burn (Visible Storage), 2019. Wooden platform, digital photos and printed vinyl on lasercut wood, chroma key fabric, printed backdrops, seamless paper, artificial plants, mixed media. Overall 20 x 17 x 8 feet. Photo: Dusty Kessler. Courtesy of the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco, and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York.

While several bodies of work in this exhibit specifically address Filipinx representation, Syjuco’s work also addresses representation and constructed narratives in more generalized ways. One work in the show features 20 digitally printed flags suspended from the ceiling; their presence evokes the United Nations, and initially they seem to be an expression of unity. But these flags come from fictional rogue/enemy states portrayed in American and European movies; none of these states existed in reality. Most of these are from films produced during the cold war, and are stylized to evoke certain parts of the world; together they speak to a generalized fear of a foreign enemy.

Syjuco’s work is heavily based on archival research, and it raises questions about how archival holdings are acquired, interpreted, and displayed. In support of this exhibit, the accompanying booklet includes brief essays by the directors and registrars of Michigan State University’s varied collections across the arts and sciences (such as the herbarium and the university archives). They discuss their holdings while acknowledging the “blind spots” that exist within these collections, underscoring the cross disciplinary relevance of Syjuco’s artistic practice.

The show takes full advantage of the Broad’s Zaha Hadid designed exhibition space. It’s both conceptually powerful and visually rich. And while the colonization of the Philippines occurred on the other side of the world, Syjuco, particularly with her Blind Spot project, reminds us of some of the ways that the enduring impact of America’s colonial legacy comes close to home.

Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum

Blind Spot: Stephanie Syjuco is on view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum through July 23, 2023