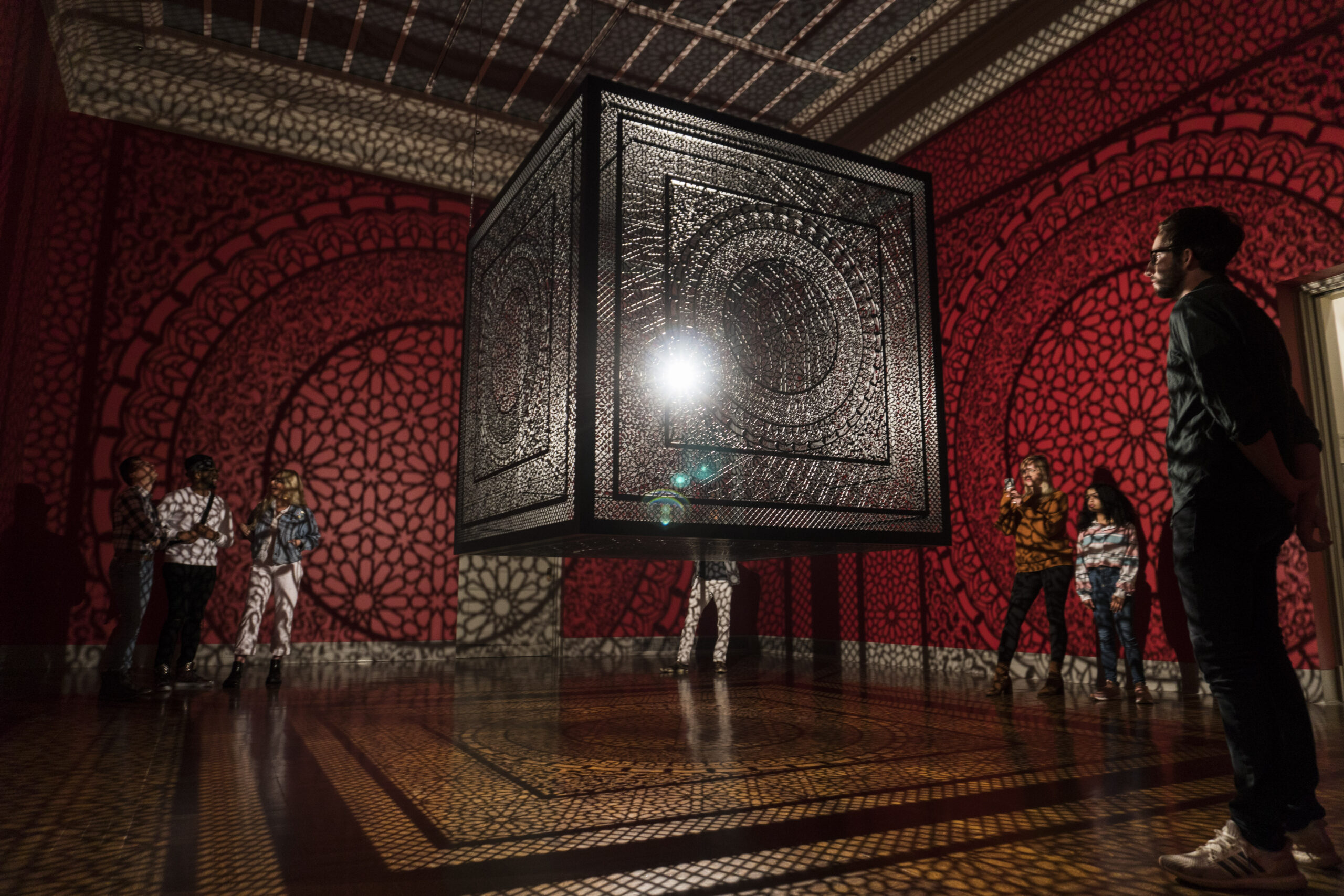

Intersections, installation – All images courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

Many in the Midwest will already be familiar with Pakistani artist Anila Quayyum Agha, whose luminous sculpture Intersections won both the Public Vote and Juried Grand Prize at Art Prize 2014, the only time this has happened at Grand Rapids’ highly acclaimed and much-imitated public art festival. Through February 9, 2020, three installations by Agha transform a suite of galleries at the Toledo Museum of Art, comprising the exhibition Between Light and Shadow. Visually, these immersive works are an extension of her prizewinning installation originally displayed at the Grand Rapids Art Museum, but these new works are subtly informed by current events, and in addition to being undeniably beautiful, they carry an understated political resonance.

In a public conversation at the exhibition’s opening with Diane Wright, the TMA’s curator of glass and decorative arts, Agha revealed that she had always faced obstacles as a female artist. In Lahore, Pakistan, where she was born and raised, she was barred entrance to some spaces open to men. In the United States where she received her MFA, one of her instructor’s, speaking from personal experience, told her to expect to work twice as hard for the same opportunities accorded to men. But Agha humorously revealed that it was the defining moment when her son, anxious for a pair of Nike shoes, asked “why are we so poor?” that she realized her only option was to face her prospects with the unflagging grit and steely determination needed to succeed, whatever the odds.

She started as a fiber artist, drawn to the medium for its practicality and commercial marketability. But her work became increasingly sculptural and immersive, gradually incorporating light and shadow. She was particularly influenced by the exploded sheds by Cornelia Parker– sheds detonated by the artist and then partially re-assembled in gallery spaces; lit by an internal light, these suspended works scatter their shadows across the gallery space, and seem to arrest a moment in time, mid-explosion. Looking at Agha’s works in Between Light and Shadow, all of which are illuminated from the interior, it’s easy to detect Parker’s influence.

Though these works are variations on a common visual motif of diffused light and shadow, each of the three installations in this exhibit subtly convey different aims. The centerpiece that anchors the show is a variant of her Intersections. In this iteration, the sculpture is metallic, yet, suspended from the ceiling by barely noticeable thin cables, it appears to hover weightlessly and the gallery transforms into an ethereal space in which the Earthly laws of physics no longer apply. The cube’s complex geometric arabesque patterns are direct quotations from the Alhambra in Spain, a place historically associated with religious and ethnic tolerance during Moorish rule of the Iberian Peninsula. Though all the versions of Intersections apply the common motif of an internally-lit suspended cube, subtle variations ensure that wherever these works are displayed, viewers will never experience the same environment twice. Here, the red walls of the gallery space were inspired by the red wedding dress a Pakistani bride traditionally wears on her wedding day.

Occupying the two other rooms in the gallery suite are similar installations, The Greys in Between and This is Not a Refuge! 2, and both deliver subtle social and political commentary. Like Intersections, the internally lit Greys in Between diffuses light and shadow across the gallery space. But this ensemble of laser-cut sculpted forms comprises two distinct but similar and symbiotically connected rhomboidal elements. In its original state, Agha wanted the surface of these forms to reflect the serene greens and blues she had recently encountered during a trip to the Florida Keys. But in 2017 the Trump administration’s rhetoric toward immigration became increasingly hostile, and in response Agha subsequently blackened the work, responding to the diminishing prospects of immigrants in America. In this work, Agha wanted to add the element of time; the mechanized parts of Greys in Between rotate at one revolution per hour, and viewers who linger a bit may notice the sculpture’s organic and vegetal patterns slowly, almost imperceptibly, moving across the gallery walls.

Greys in Between, installation image courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

The political undertones in Agha’s work are generally understated, but not so in the candidly titled work This is not a Refuge! 2. The sculpture is based on a previous work of the same title, a highly permeable house intended to be displayed outdoors and exposed to the elements, and thus utterly unsuitable for use as an actual shelter. The work was conceived as a response to xenophobia in the United States and Europe. Delicately applying the gentlest possible language to offer historical context, Agha says that many of the current problems which led to the immigration crisis are rooted in conflicts and wars that “the CIA may have fiddled with.” But she concluded her conversation with Diane Wright remarking that it’s precisely because she loves America so much that she feels the urge to critique it.

This is Not a Refuge!2, installation image courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

Agha’s works are poignant and timely, but she avoids the high-decibel screech and the gravitational pull to cliché which is so overabundant in our current political discourse, and somehow manages to deliver understated socio-political commentary through works of art whose transcendent beauty verges on the sublime. While they respond to real-world issues, they also impart a sense of wonder, which is perhaps what gives her work such widespread appeal. And as for her son, when an inquiring audience member asked if he ever got his coveted pair of Nike shoes, Agha was happy to report, that yes, in fact he did.

Video courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

Between Light and Shadow now on view through February 9, 2020