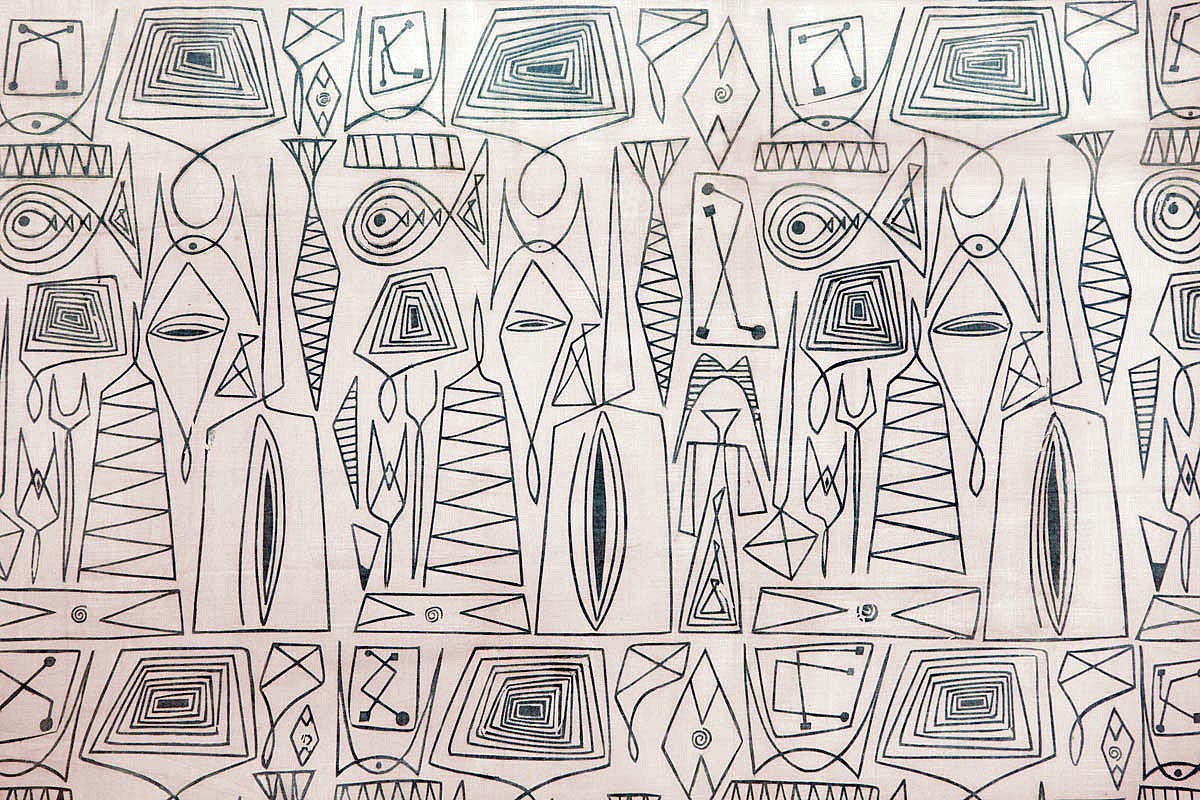

Untitled II (for Ashgebat) by Christy Matson, 2016-2019, hand-woven cotton, linen, wool, indigo dye and acrylic on stretched canvas.

Contemporary craft is having a moment. The Museum of Modern Art in New York City recently placed ceramics by George Ohr next to Van Gogh’s Starry Night in their re-installed galleries. Taking a Thread for a Walk, an exhibit that celebrates weaving and fiber art in all its forms, both ancient and modern, will be on view there until April, 2020. Meanwhile, over at the Whitney, there’s a comprehensive survey of modern and contemporary American craft from 1950-2019, called Making/Knowing: Craft in Art.

Members of the Cranbrook arts community might be forgiven for asking what took so long; since its founding in 1922, Cranbrook has been a champion for American craft traditions. The museum seems to be taking a victory lap for its prescience right now: 4 exhibits on view through March carry the vision of craft as art forward while also looking back at important moments of its history, in Detroit and beyond.

Wireworks by Ruth Adler Schnee, 1950, ink on white dreamspun batiste

Ruth Adler Schnee: Modern Designs for Living

A major retrospective (her first) of eminent Detroit textile and interior designer Ruth Adler Schnee occupies the museum’s front gallery. Adler Schnee’s family fled Nazi German in 1939, settling in Detroit, where she attended Cass Technical High School. After earning a degree in design at the Rhode Island School of Design, Adler Schnee returned to Detroit to study architecture with Eliel Saarinen at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, graduating in 1946. She faced obstacles as a woman to a career in the male-dominated field of architecture, but immediately found success in textile design. Her memorable modernist cotton prints are on display and will be immediately familiar to anyone who feels an affinity for the recently resurgent interest in midcentury modern design.

Ruth Adler Schnee made it her mission to democratize good design for the post-war mass American market. “We are living in a democracy. Our designs for living must have social implications,” she states in her Cranbrook master’s thesis. She worked extensively as an interior designer and textile designer with architects like Minoru Yamasaki, Frank Lloyd Wright and Eero Saarinen, as well as operating (for 30 years with her husband Eddie) Adler Schnee Associates, a retail design business in Detroit. She also worked with American car companies; for an amusing look at their symbiotic relationship and a historic overview of the importance of Detroit as a driver of design in the 50’s and 60’s you can view American Look, a 1958 promotional film sponsored by Chevrolet.

At 96, Adler Schnee continues to be a relevant force in textile design today through adaptation of her classic printed textile designs into woven fabrics and carpet design. Examples of both are on display in the gallery.

Designs Worth Repeating, Woven Textiles by Ruth Adler Schnee. Woven fabrics based on Adler Schnee’s mid-century modern prints, re-introduced for the 21st century.

Christy Matson: Crossings

Contemporary L.A. fiber artist Christy Matson is a multi-disciplinary shape shifter whose work occupies an esthetic space at the intersection of painting, weaving and collage. Employing digital technology and a jacquard loom, Matson expands the formal parameters of weaving. She creates tapestries that incorporate organic curving lines and shapes unavailable via more traditional techniques and employs novel fibers and pigments added to traditional yarns and threads. The results are fiber artworks that have been aptly described as “painterly.”

Crossings, a solo exhibit of her work currently on view at the museum, consists of two large tapestries realized as a commission for the U.S. Embassy in Ashgebat, Turkmenistan, as well as several smaller, more intimate pieces that allow a welcome closer look at Matson’s technical means.

Matson has an expressed interest in the symbolism and the technical realization of traditional Turkmen textiles, as well as a kinship with the women who make them. The traditional costumes of Turkmenistan are deeply symbolic and incorporate imagery specific to the gender, social position and age of the wearer. Varieties of technical decoration in local costume, such as patchwork and embroidery, make a richly colorful and tactile pastiche that relates formally to Matson’s work. The rugs for which the region is justly famous are woven by women from a variety of fibers dyed with a combination of synthetic and natural dyes, another point of correspondence with the artist.

Untitled I (for Ashgebat) by Christy Matson, 2016-2019, hand-woven cotton, linen, wool, indigo dye and arcylic on stretched canvas.

The two colossal tapestries that anchor the exhibition incorporate abstract pattern and stylized images of plants using long narrow woven panels joined two by two. Untitled 1 (for Ashgebat) consists of stripes and floral motifs that are repeated and occasionally reversed and tilted to yield a roughly symmetrical counterpoint. A central stylized blossom anchors the composition. Untitled II (for Ashgebat) flirts with the illusion of pictorial space. The hazy vertical stripes on the left suggest grasslands, while the same lines reversed and repeated on the right suggest the fringe of a rug. The stylized seed heads and blossoms on each panel create a satisfying rhythm without precisely repeating themselves.

The smaller pieces in Crossings allow a closer look at Matson’s art practice. Particularly illuminating is her Overshot Variation 1 which incorporates bands of painted paper using the overshot technique often employed in Jacquard weaving.

Overshot Variation I by Christy Matson, 2018, deadstock overseen linen, acrylic and spray paint on paper, Einband Icelandic wood

In the Vanguard: Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, 1950-1969

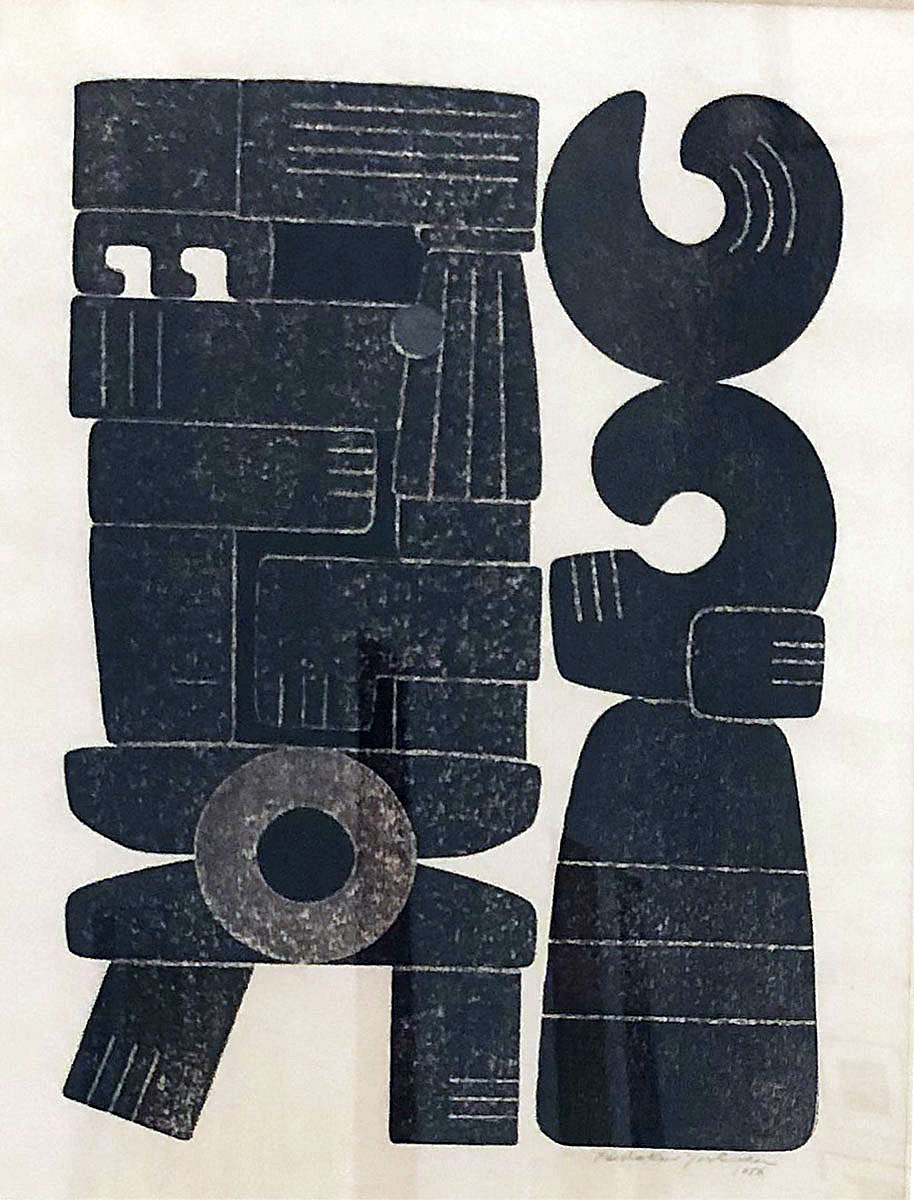

For artists who dream of an idyllic creative space where collaboration, mutual support and disciplinary cross-pollination are the rule, the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts represents a dream come true. The 90 pieces that fill, and threaten to overflow, the museum’s middle galleries recount the history of this important creative community from 1950-1969 for the first time. The objects in the exhibit range from textiles to printmaking, ceramics, metalwork and painting, and even to jewelry making and glass art. By discarding ideas regarding the primacy of fine art versus craft, the members of Haystack approached a non-hierarchical egalitarian ideal. Many of the artists represented in the exhibit also had ties to the Cranbrook arts community during a particularly fertile period for craftspeople who lived and worked and created in this uniquely supportive creative environment.

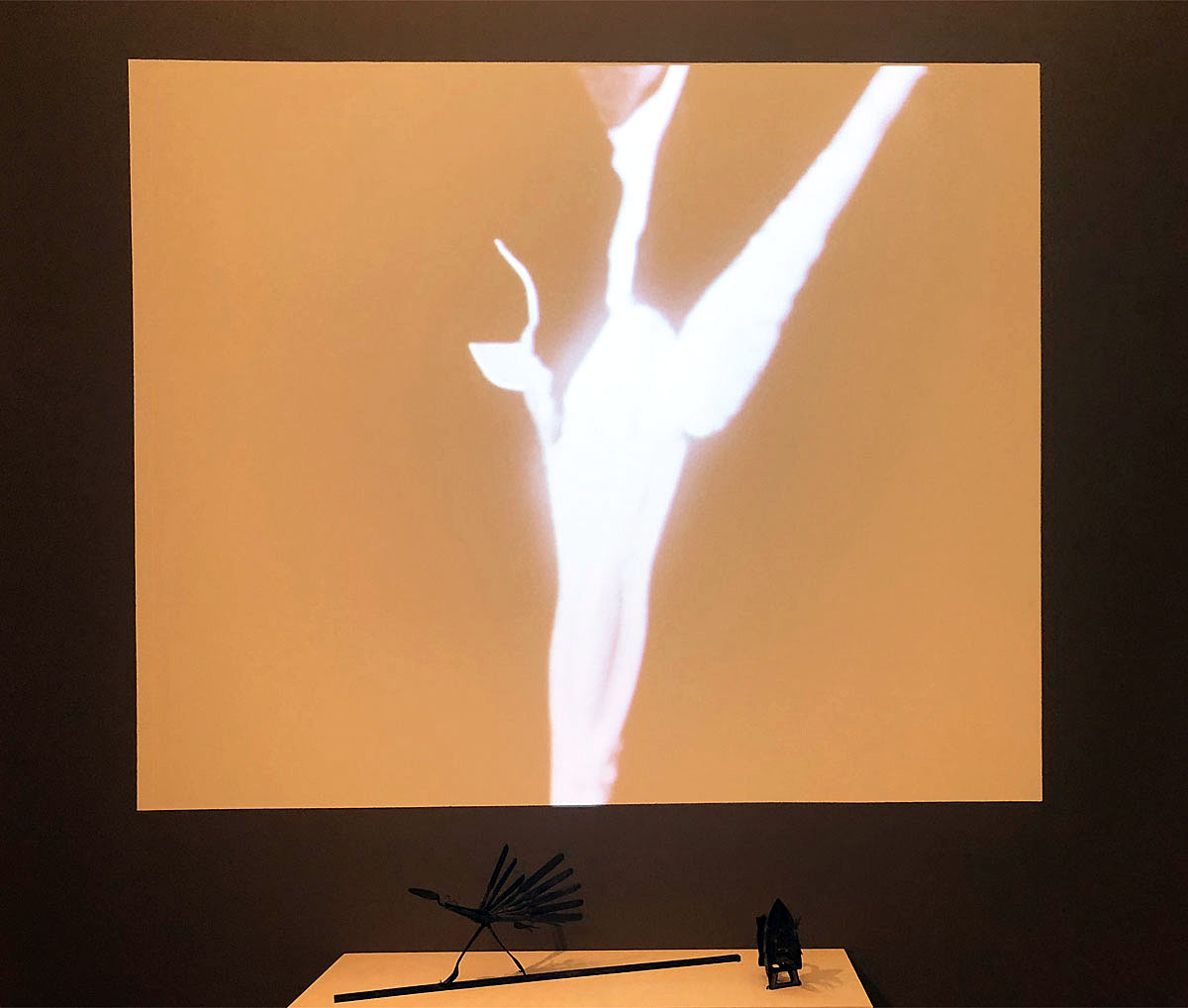

Video still, from Dance of the Looney Spoons, by Stan VanDerBeek with Johanna VanDerBeek, 1959-1965, 16 mm black and white film transferred to video with sound, 5:20 minutes (Haystack)

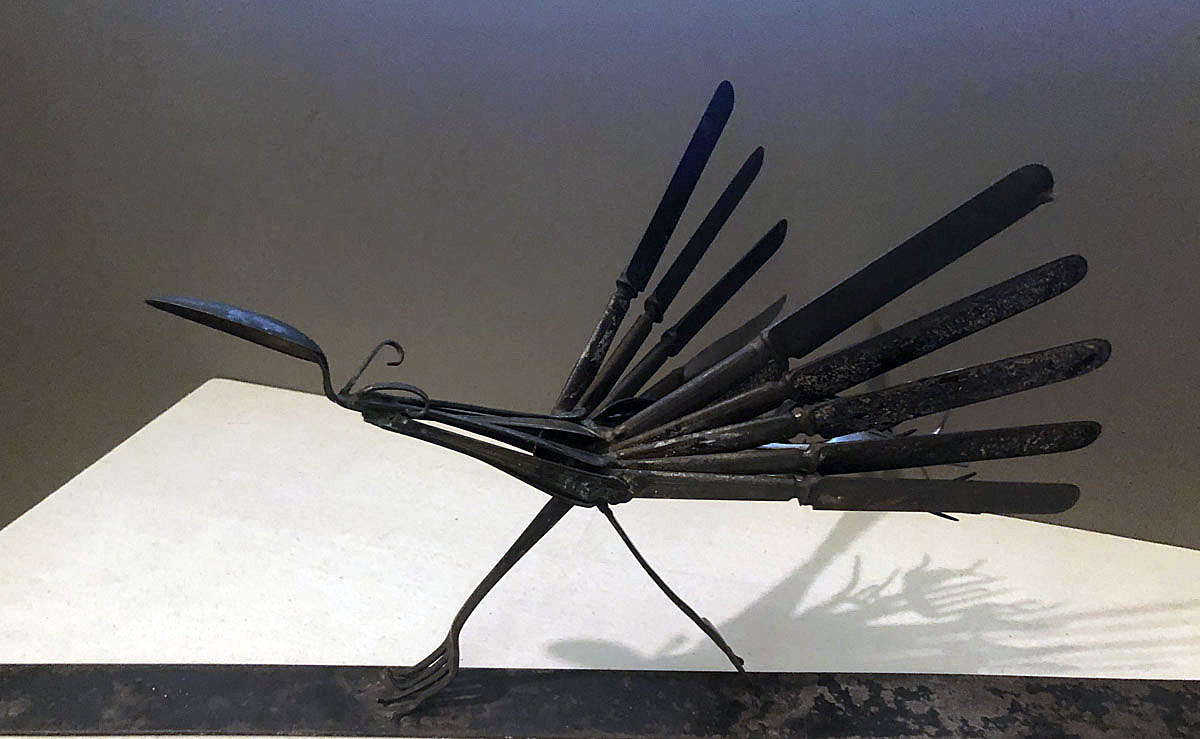

Silver Road Runner by Stan VanDerBeek, 1954, assorted metal silverware (Haysta

Ancient People by Hodaka Yoshida, 1956, relief print on paper (Haystack)

For the Record: Artists on Vinyl

In the lower level gallery, you can experience the unexpected pleasure of 50 designs for vinyl records–some vintage, some recent– by a who’s who of artists comfortable working at the intersection of design and fine art: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Yoko Ono, Andy Warhol, Banksy, Shephard Fairey and Keith Haring, Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Motherwell, to name only a few. The square parameters of the vinyl record cover seem to have offered the perfect creative space for artists to create bite-size versions of their more ambitious works. It’s worth a trip down the stairs just to see Jean Dubuffet’s painting Promenade a deux from the museum’s collection, installed next to his lithograph Musical Experiences.

Promenade a deux by Jean Dubuffet, 1974, vinyl on canvas, matt Cryla varnish

The exhibits at Cranbrook right now, particularly the Ruth Adler Schnee retrospective, demonstrate some of the diverse ways in which craft and design have historically influenced America’s aspirational culture. The built environment of the country, though, has changed–is changing. As the past gives way to the future, the times will require creatives that bring the same level of creativity seen here to new challenges like technological innovation and environmental change.

Winter at Cranbrook Art Museum: Craft Takes a Bow through March 15, 2020