Five-hundred-year floods, particularly in the midst of a pandemic, don’t ordinarily generate intriguing art shows, but that’s precisely the origin story of “Notes from the Quarantimes” at the Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Museum in Saginaw through Jan. 15, 2022.

Following a seven-inch deluge in May 2020, the Edenville Dam north of Midland crumbled, disgorging, according to the “Quarantimes’” program with the artist statements, 22.5 billion gallons of Wixom Lake that gushed downstream, in minutes scooping out the original route of the Tittabawassee River, uprooting houses and fully grown trees alike. One of the homes near the dam, damaged but not destroyed, has been owned by artist Andrew Krieger’s family since 1955.

“Notes from the Quarantimes” is up at the Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Museum on the Saginaw Valley State University campus through Jan. 15, 2022

“It was nutty,” Krieger said of the day the waters rose. “A Consumer’s Power guy who was nearby said our house was going to float away any minute” — but perhaps miraculously, it did not. That said, things were nip and tuck for a while, but the Kriegers essentially lucked out. Their basement was submerged and ended up with a foot of muck at the bottom, but the waters stopped eight inches short of their first floor. The wooded area around the house, however, was turned into a veritable moonscape in a matter of hours, with craters where entire root systems of giant trees had been wrenched free. Krieger figures they lost about 100 trees, many planted by his father; his brother says 200. In any case, the clean-up task was herculean. The day after the flood, an exhausted Krieger texted five of his best art buddies: “I need help. Overwhelmed and sad.”’

They all rallied. In short order, Mitch Cope, Scott Hocking, Michael McGillis, Clinton Snider and Graem Whyte were all at the house, and each of them would continue to return on a regular basis over the next year, a nice testament to the quality of the friendships involved.

Krieger says the group had already been talking pre-flood about doing an exhibition together but hadn’t yet hit on a concept. “I think,” he added, “it was Graem Whyte who said, ‘This is the show. It’s about us coming up and helping you, and Edenville, and this pandemic.’” The result is a good-looking, spirited exhibition of considerable artistic diversity that reflects both the Sturm und Drang involved in simultaneously coping with a vicious virus and the cataclysmic consequences of climate change.

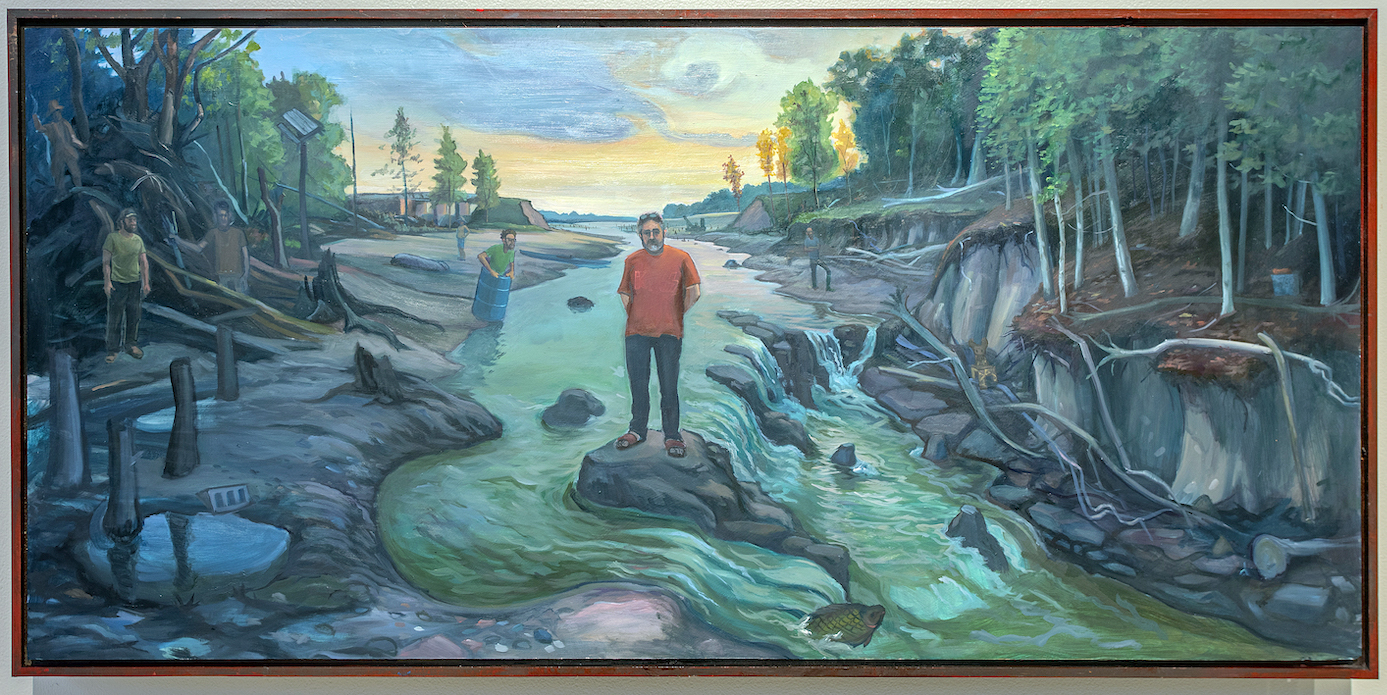

Clinton Snider “After the Flood,” Oil on panel, 2021

Clinton Snider’s “After the Flood” tackles the catastrophe head-on, with a melancholy portrait of the six friends surveying a ravaged landscape, with Krieger himself at center standing on a rock surrounded by the newly trenched stream. Like so many of Snider’s paintings, the light is muted and sepulchral – the artist says he favors early dawn light. In tone and feel, “After the Flood” evokes much the same mournful vibe as Snider’s 2005 portrait, “Studebaker Razed,” which captured the abandoned Detroit factory the morning after its catastrophic fire.

Another compelling visual statement directly tied to the dam disaster is Whyte’s amusingly titled “Batten Down the Hatches.” This large installation, lying prone on the gallery floor, stars a debris pile bound together with yellow ratchet straps. Among its disparate elements are a toppled ornamental lamp post – its five globes still lit, in a nice touch – and a tree-length log with long, carved toes, as if Treebeard, the walking, talking, tree-like “ent” in “Lord of the Rings,” had lost a limb.

Graem Whyte, “Batten Down the Hatches,” Maple, found lamp post, cast aluminum, wheel, paint on wood, ratchet straps, 2021

And don’t miss – well, really you can’t miss – Whyte’s “Vortex of Janus” smack in the center of the gallery. This mechanical construction on wheels is very big, maybe five feet tall, or so – a tapering, octagonal, open-ended kaleidoscope. The interior metal sides appear to be swirling, a nice optical illusion created by a pattern of clean, sharp-edged parallelograms and the occasional through-line in vivid hues. Besides creating an intriguingly kinetic visual – you immediately see how water forced through the vortex would rush out the smaller end with multiplied force – this is an elegant, absorbing color study dominated by shades of green, black, and surprising bursts of orange and lavender.

Funny and tragic both is Michael McGillis’ “Poseidon’s Throne” that blends a reference to cottage life with ugly reality. In his artist’s statement, McGillis says he’s always been interested in landscape and human scale, and with “Throne” he’s sculpted a convincing diorama of a bend in a new stream that’s clearly raked its way through a now-barren landscape. At one end, as if to underline the absurdity of it all, a cheerful, orange Adirondack chair sits mostly submerged, already acquiring a green, river-scum patina below the waterline.

Michael McGillis, “Poseidon’s Throne” (detail), Mixed media, 2021

Dominating the far wall as you walk in is Scott Hocking’s sizable installation, “Woodsmun of the Forest,” as well as one of two videos the artist made while kayaking around both the Edenville disaster and waterways in the Detroit area. Sparingly narrated by Hocking, the videos — in particular “Kayaking through the Quarantimes” — are mesmerizing, pretty gorgeous and, on occasion downright funny.

HOCKING VIDEO: “Kayaking through the Quarantimes” 19 Minutes

For its part, “Woodsmun” is a triptych comprised of large tree parts that were either submerged almost 100 years ago when the Edenville Dam was erected or else fell or washed in sometime over recent decades. The central element is a huge, distressed trunk partly suspended from the ceiling, framed by smaller, sculptural wood forms. In a puckish touch mostly on the backside of the installation, Hocking’s integrated man-made artifacts – some would say trash – that he retrieved from the drained lake, including a rope, rusted beer cans, and a large ornamental daisy that’s got “1970s perky bad taste” written all over it.

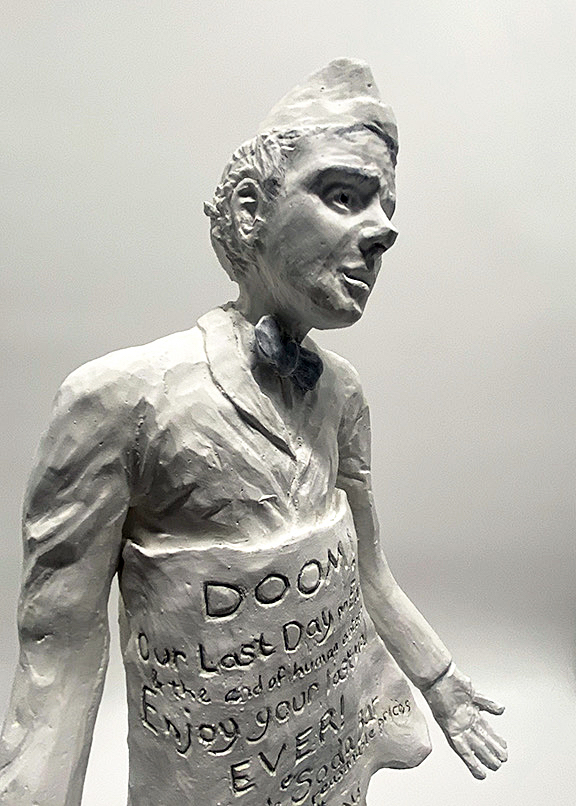

For his part, Krieger has mounted a number of color photographs of what remains of the dam, as well as landscapes including “Tittabawassee Sunset #1.” That image fills up a clear, cylindrical container rather like a scientific specimen, or last year’s preserved tomatoes. But the artist’s biggest crowd-pleaser is likely to be “Last Day on Earth,” an off-white ceramic sculpture of a hopeless fellow maybe two feet tall with a sign wrapped around his midriff that proclaims “DOOM,” and adds, just to make sure passers-by get the point, “Our last day on earth and the end of human existence.”

Andrew Krieger, “Last Day on Earth,” Ceramic, 2021

But apocalypse or no, this being America, as you read down you realize the sign’s actually an ad urging you to “enjoy” your last meal at Howie’s Soda Bar with its celebrated “good food” and “reasonable prices.” Because even in the midst of apocalypse, you want value for your money, right?

Finally, standing somewhat apart in tone and size are Mitch Cope’s three colored-pencil water lily studies. Each of these large, square canvases also invokes one of three planets in a somewhat cryptic fashion – specifically the moon, Saturn and Jupiter. They’re handsome, restful works. In a show devoted to destruction, Cope’s vividly colored drawings radiate hopeful calm and underline the healing power of looking closely at nature. The three are a lovely balance to the sharper narratives on display all around them.

Mitch Cope, “Water Lili #1 Jupiter,” Colored pencil on paper, 2021

Clinton Snider, Tree of Eden, 2021, 53 sec.

“Notes from the Quarantimes” is on display at Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Museum through January 15, 2022.