Taking a hard look at the “hard edge”

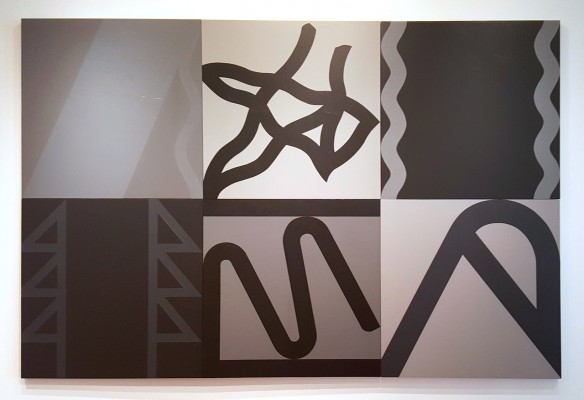

Viewing just the south-facing wall of the main gallery at David Klein Gallery’s new downtown Detroit location, you might never imagine that there are three different artists included in the current show, Economy of Form: Matthew Hawtin, Mary Kim, and Mark Sengbusch, which held its opening reception on November 14th, and will run through December 24th. Closest to the door is Pitch, a six-sided monochrome piece in matte black by Hawtin—a dimensional canvas that resembles an iconic jewel shape tipped on its side. This flows in seamless conversation with Kim’s Two circles, which conveys two roughly circular forms made out of rigid lengths of wood, likewise bending outside the 2D plane, and swathed in bright acrylic shades of chartreuse and red. The wall terminates in Sengbusch’s Gibson 6, which distills his signature set of symbols, laboriously scrimshawed into acrylic-painted wood, into six scaled-up details in shades of matte black and grey.

Spare arrangements, vibrant monotones, and careful use of geometry is present in all three bodies of work, and the exhibition title refers to a characteristic of the term “hard edge,” first applied to Four Abstract Classicists, which opened at the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1959. The artists featured in the 1959 show were John McLaughlin, Lorser Feitelson, Frederick Hammersley, and Karl Benjamin, and give clues to some of the formal inspiration for the artists on display at David Klein—as indeed they have spawned entire generations of work springing from these starting points, including that of Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Indiana, Paul Feely, and numerous others. Perhaps rising less automatically to mind and representing a more unique expression of these artists individual visions are some wellsprings of inspiration that fall outside the contemporary arts canon; Kim’s second Master’s degree in architecture transformed her previously more traditionally 2D approach to painting into the 3-dimensional constructions that just from the walls at hard angles; Hawtin’s almost two-decade long experiments with the “torqued canvas” that removes the physical structures of the painting stretcher and frame; Sengbusch’s obsession with seminal science fiction writer and visionary futurist William Gibson.

In some ways, the three artists in this group show work together so perfectly because they have each chosen to zoom into the fine details of one traditional element of painting—Kim’s works are entirely stretcher and or/frame, Hawtin’s are obsessed with the canvas surface (sometimes actually fiberglass, affording a preternaturally smooth finish), and Sengbusch has generated an elaborate vocabulary of original signifiers. This last elevates Sengbusch’s work to a unique level, translating his source material into a visible and new language that goes beyond art history, and breaks into future territory. But while writers like Gibson are necessarily preoccupied with the meaning of words, Sengbusch is concerned with the form, the literal design of language—a rich subject for investigation. To create language without meaning is a truly difficult task, when you consider the awesome power of the human mind to translate symbols as diverse as a musical note, hànzì or kan’ji (Chinese and Japanese characters, respectively), or the letters you are currently reading into meaningful sounds, and Sengbusch’s finished canvases of course lend themselves to interpretation, when viewed by anyone trained to seek meaning from signifiers.

Altogether, a very strong show at David Klein Gallery, with allusions to the rich lineage of minimalist and hard edge traditions, and a few new twists thrown in to keep the conversation moving!

Economy of Form: Matthew Hawtin, Mary Kim, and Mark Sengbusch remains on display from November 14 – December 24, 2015 at David Klein Gallery – 1520 Washington Boulevard, Detroit