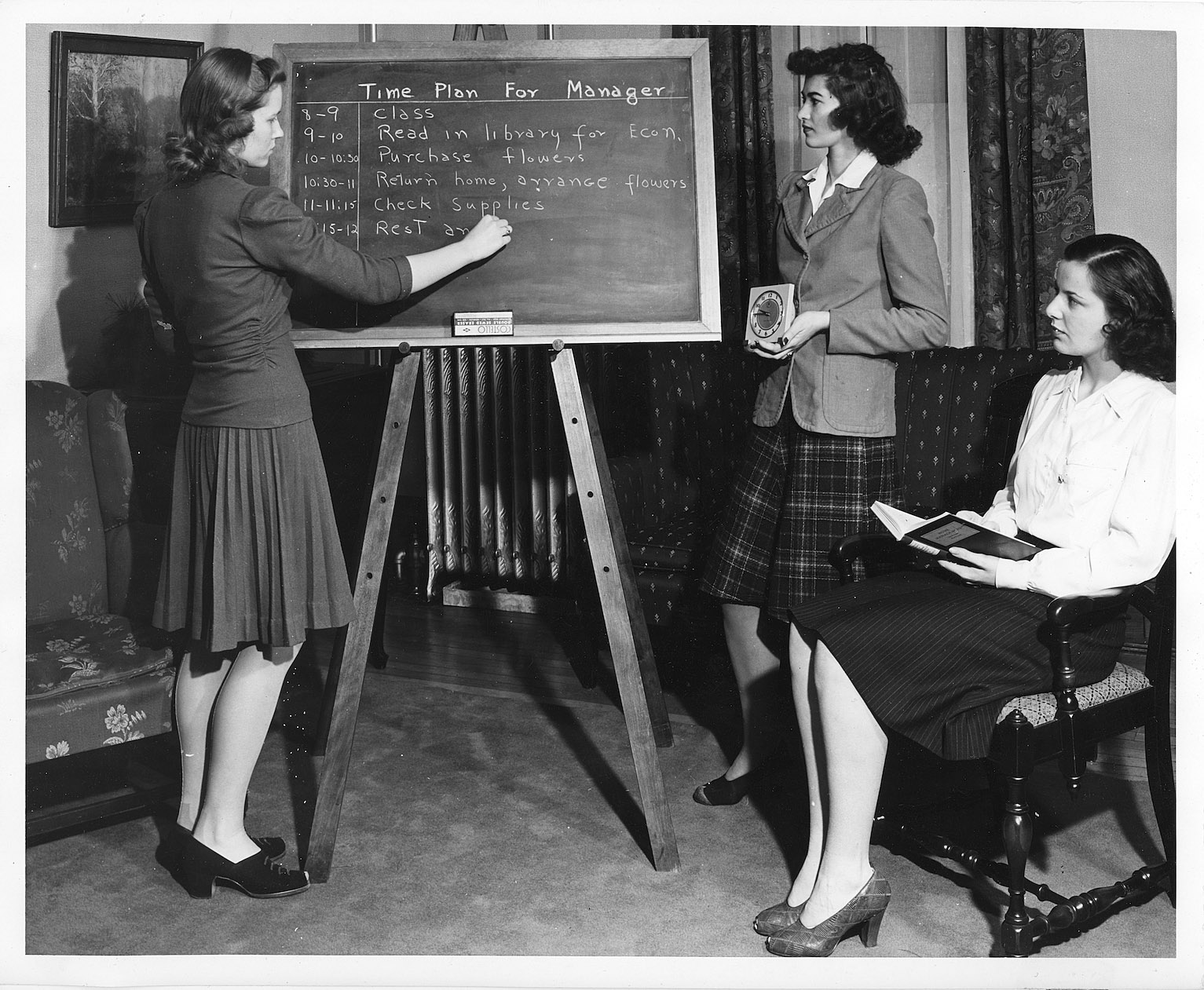

Form&Seek: Poetic and Tending Time: Megan Heeres @

Matéria Core City Gallery

Opening night reception for new work by Form&Seek and Megan Heeres at the new Matéria building (previously Simone DeSousa Gallery) September 9, 2023. Images courtesy of Materia Core City.)

Well, the day has finally arrived. After a few of the usual construction delays, Matéria, gallerist Simone DeSousa’s new cultural campus, has opened in Detroit’s Core City neighborhood. Matéria’s first suite of exhibitions, performances, and events extends from September 9 to October 7 and contains multitudes.

The newly opened building houses the tenth-anniversary exhibition of fine craft objects by Bilge Nur Saltik, founder and creative director of the design collective Form&Seek, plus an installation by fiber artist Megan Heeres and Puma, a casual ceviche bar created by Chef Javier Bardauil of Barda. An eclectic and eccentric schedule of activities and activations in the galleries and in the nearby park include performances by dancer/choreographer Biba Bell with Christopher Woolfolk and Shannon White and music by Matthew Daher. An invitation-only dining experience from Detroit’s farm-to-table collaborative Coriander will round out October’s scheduled activities.

The name Matéria points to a new direction for gallery director Simone DeSousa. While she will retain her former intimate jewel box gallery on Willis Avenue for shows featuring established Cass Corridor artists, DeSousa sees the new Matéria space as a laboratory for experimentation and for the presentation and promotion of new voices and visions in Detroit. “Our new name signals the beginning of a new era of collaborations for our project, as we expand our presence in the city with a second space,” she stated in a recent press release.

Performance park outside the Matéria building, designed by Julie Bargmann of D.I.R.T. Studio, assisted by Andrew Schwartz. Materials gathered from the surrounding environment. Image courtesy of K.A. Letts.

Matéria Core City and its adjacent park and performance space are only the newest additions to the Core City neighborhood project as envisioned by entrepreneur and developer Philip Kafka of Prince Concepts. The elegantly appointed three-chambered building, one of Detroit’s many formerly unprepossessing low-rise commercial buildings, now transformed into an art, dining and cultural destination, is one of a complex scattered along Grand River Avenue. They include (among others) the Caterpillar and True North, two residential developments, The Magnet, which houses the Argentinian restaurant Barda, and 5k, a former grocery store imaginatively re-configured to serve as headquarters for the marketing firm OLU & Company. In a recent brief interview at the site, Kafka described his philosophy of development in Core City as a leveraging of local human talent and on-site resources, both natural and architectural, in service to a new vision of contemporary Detroit. Kafka thinks of his collaborations with creatives and the urban environment as a kind of metaphorical jazz improvisation to achieve a result that no single player could arrive at alone.

Installation Form & Seek: Poetic. Clockwise from left: Entwine Rug, 2023, tufted wool, 74” x 56” x 2”; Entwine Rug 2023, tufted wool, 64” x 66” x 1”; 3D Printed Stool (Blue) 2023, 3D printed PLA plastic, 18” x 28” x 16”; 3D Print Table, 2023, 3D printed PLA plastic, glass, 20.5” x 32”; Frosting Lamp, 2023, 3Dprinted PLA plastic, 16” x 9”

Form&Seek: Poetic

Within the first of the three adjoining spaces of the new Matéria building, the design collaborative Form&Seek celebrates its tenth year of existence with an exhibition of all-new work by Bilge Nur Saltik. Entitled “Form&Seek: Poetic,” the objects displayed explore the ever-more-symbiotic relationship between craft and technology in a pristine gallery environment. The exhibition coincides with the thirteenth anniversary of Detroit’s Month of Design.

In the ten years since its formation in 2013, Form & Seek has employed the talents of over 90 designers from 20 different countries to produce a diverse collection of one-of-a-kind objects that can be described as both objects for everyday use and fine art. The Form&Seek esthetic philosophy “places a strong emphasis on craftsmanship, materials and the creative journey… [and is] dedicated to crafting one-of-a-kind, functional and whimsical objects.”

Sensuous yet cerebral, the artifacts created by Saltik for “Poetic” often employ 3d printed technology. A variety of scales are represented, from large tables, stools and lamps to smaller vases and planters. A particular beauty is the elegant 3D Print Wall Sculpture, three white shapes that seem to reference classical Greek columns. Also featured are four wall-mounted tapestries that combine the cozy familiarity of tufted wool with voluptuous, thickly curving shapes in a variety of colors ranging from dusty pastels to saturated ultramarine blue. They seem animated as if the constituent ropey lines were alive and writhing on the wall.

Installation, Megan Heeres, foreground: Somewhere…Else, 2023, paper thread (shifu) from knotweed and grass plants on site, latex paint, repurposed wire and webbing from site, found mirror. Background: Forever Forest, 2023, repurposed duct work and lumber, live plants from site, casters, pigmented paper pulp with growing grains and time. On the back gallery wall, Angle of Repose (Mound Mapping,) 2023, soil from site, fabric, glue.

Megan Heeres: Tending Time

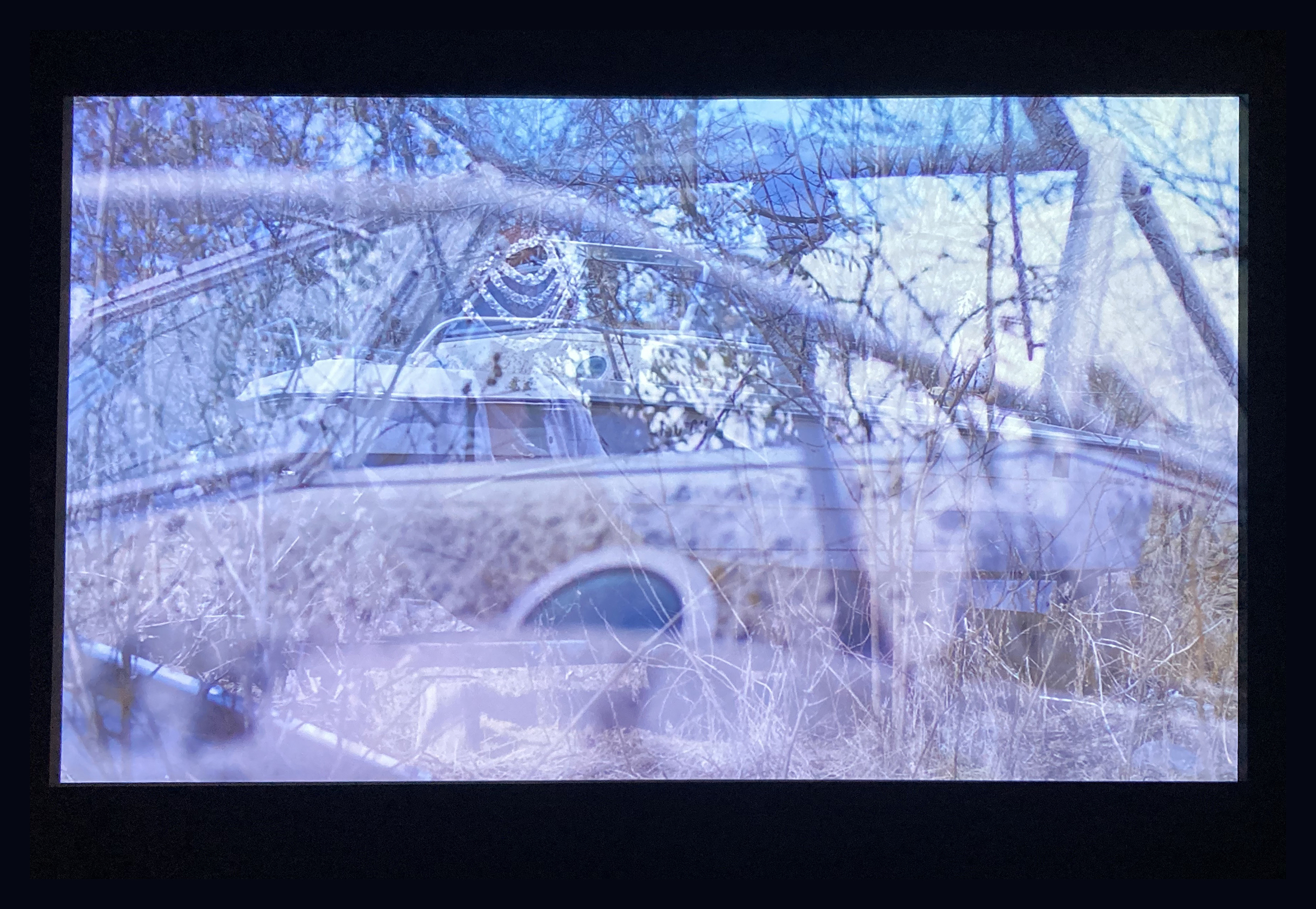

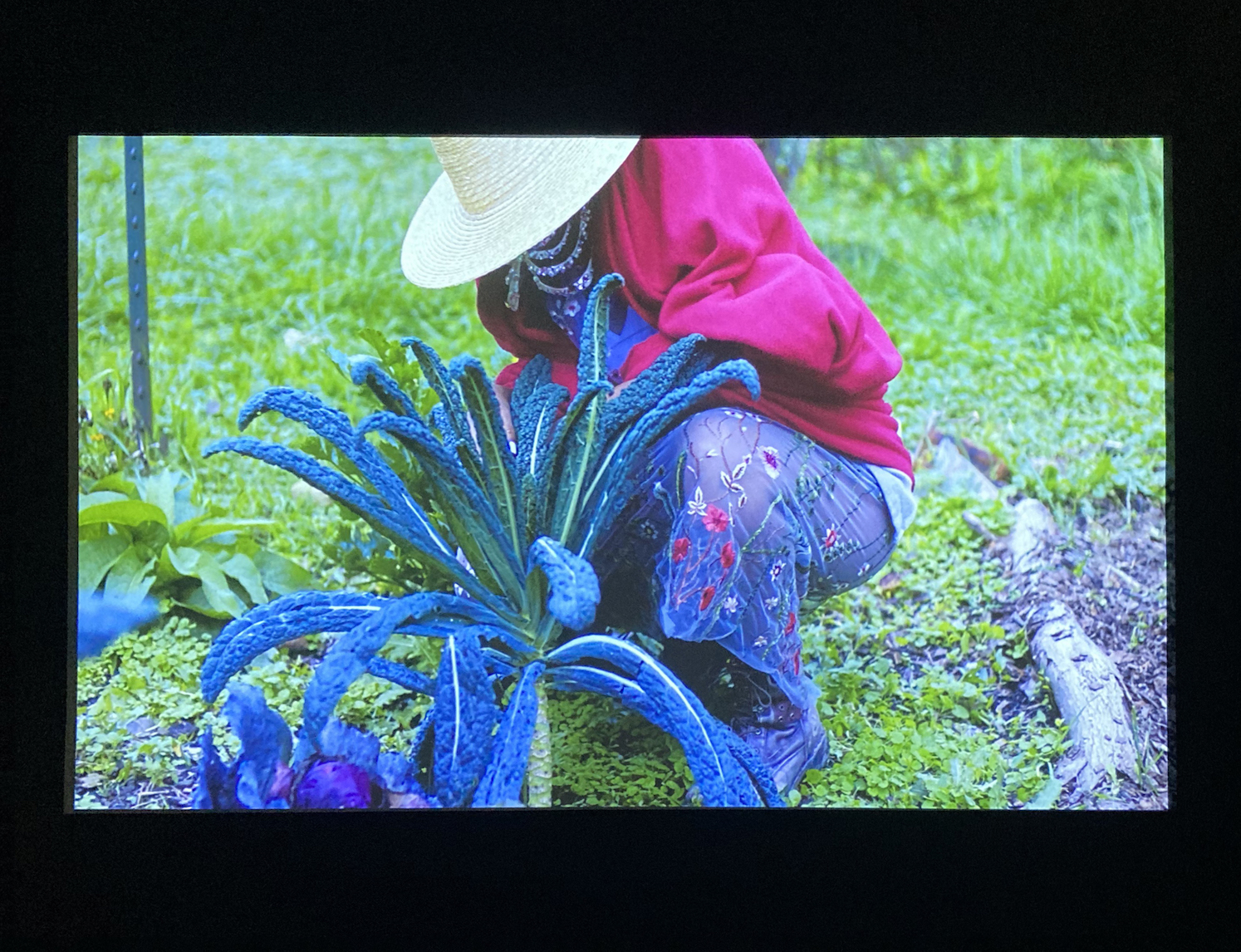

Of all the artists that DeSousa could have chosen for the inaugural exhibition at Matéria, fiber artist and urban forager Megan Heeres most clearly exemplifies, in fine art form, many of the concepts that animate the Core City esthetic. Heeres is no stranger to the upcycling of building materials, keen observation and thoughtful use of indigenous plant material and engagement of community members in the realization of her projects. For her installation “Tending Time,” Heeres has gathered found materials from the site—repurposed pipes, salvaged lumber, brick, terrazzo and asphalt, even dirt. She uses the found components from the immediate neighborhood to create an immersive environment of stylized columnar trees and impromptu low walls that lean casually against the building, both inside and out.

In Forever Forest, Heeres has placed white columns of salvaged duct work, close-packed together, in a forest of post-industrial pillars that terminate at their tops in explosions of greenery. In the front of the space, Somewhere Else, a u-shaped swag of paper thread made from knotweed and grass mixed with latex paint and re-purposed wire, loops from ceiling to floor and is echoed on the back wall of the gallery by an inverted arch, Angle of Repose (Mound Mapping) made of local soil.

Installation, Megan Heeres, Stacks on Stacks on Stacks, 2023, repurposed concrete, brick, terrazzo, asphalt from site, with grains (wheat, rye, buckwheat, millet) growing in pigmented paper pulp, time.

In the spirit of Core City collaboration, Heeres has also created wearable artworks made from her signature, locally fabricated fiber, to clothe dancer Biba Bell and two colleagues for a performance of concrète: a new dance that was performed on Saturday, September 16.

This middle (and as yet unnamed) exhibition venue is intended as a gathering/dining venue as well as a gallery. Its inaugural offering will be an invitation-only dinner on October 4 featuring a menu from Coriander Farm, which bills itself as “the only restaurant in Detroit that is the farm AND the table.”

The third space within the new Matéria building–and still under construction–is Chef Javier Bardauil’s Puma, a casual bar where thirsty art lovers can retire for a variety of beers, cocktails and light fare.

Immediately outside the Matéria building, a newly opened park makes the most of the neighborhood’s abundant open space. Designed by D.I.R.T. Studio’s Julie Bargmann and assisted by Prince Concepts’ Andrew Schwartz, the park seems to arise naturally from the surrounding environment, a “found” space that makes the most of materials at hand. Bargmann explains, “It’s about staying within the spirit of Detroit, which is a whole lot of spontaneous vegetation…It’s the new palette. It’s the new woodland. These projects are part of that.” Permanent and temporary artworks are envisioned for the future, and the park will host performances planned on a schedule developed by Matéria.

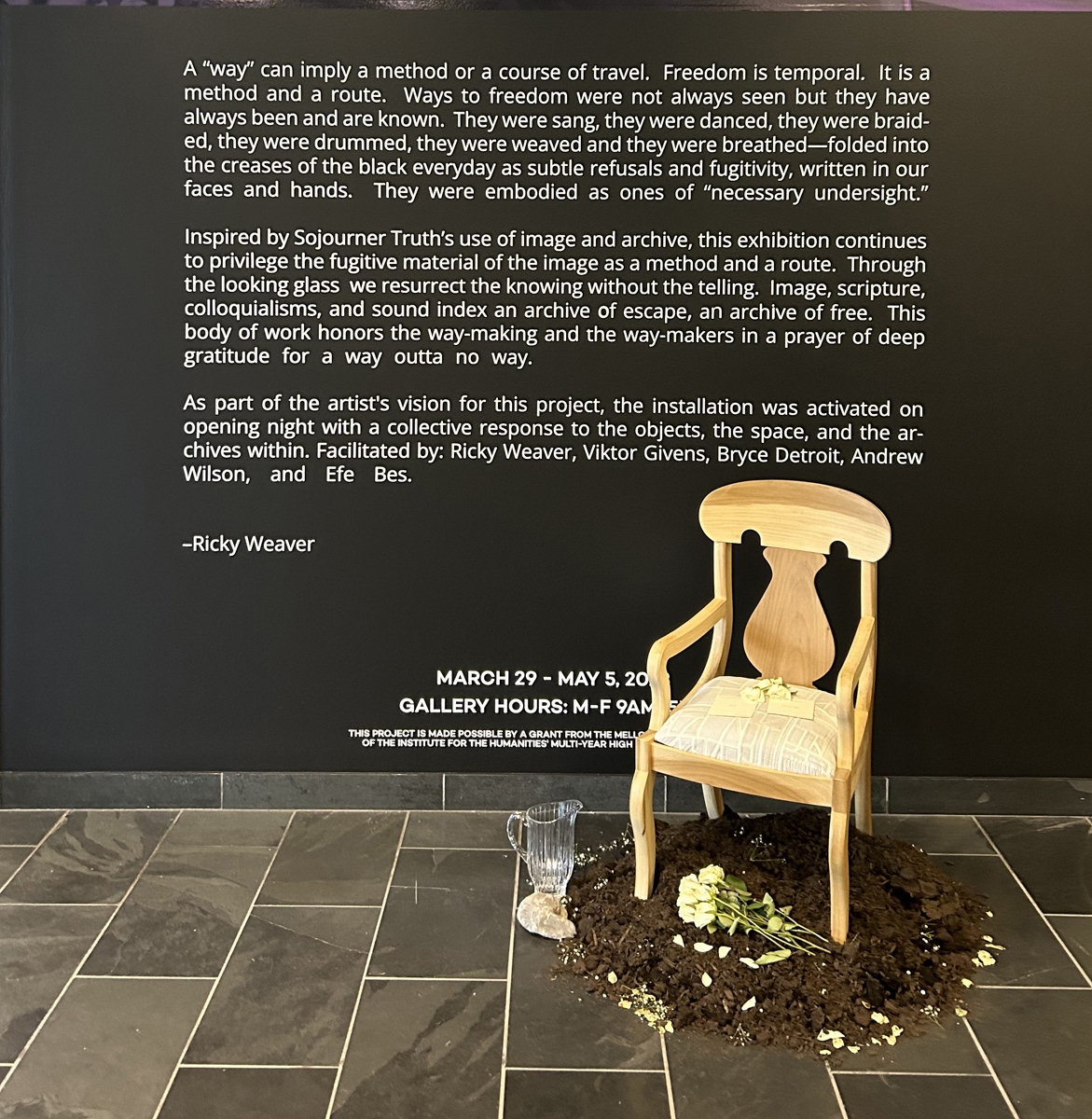

The cultural campus that is organically coalescing in the Core City neighborhood is exemplative of an increasingly visible attitude among artists and other creatives. They favor hybrid spaces that lend themselves to performance, dining and social interaction in addition to their function as venues for fine art. Rather than a pristine white box gallery devoid of context—a cultural monoculture, if you will–artworks can now be displayed in more natural, approachable environments that allow for a variety of esthetic experiences.

The design philosophy underpinning Matéria—and behind Core City more generally–makes a potent argument for thoughtful, non-hierarchical and multivalent development of public spaces. This reassessment of conventional ideas about placemaking recognizes the intrinsic value of Detroit’s natural landscape and proposes to build upon it toward a richer, more welcoming and accessible habitat for the city’s art community.

Matéria, Opening reception at new Materia Gallery, September 14, 2023