General Rules Do Not Apply at Ferndale’s M Contemporary gives a quick, refreshing tour of the lyrical possibilities of colorful abstraction produced by an intriguing set of Detroit artists: Matt Eaton (now in Los Angeles), Lauren Harrington, MALT, Jaime Pattison, Senghor Reid, Zach Thompson and Dino Valdez. General Rules is up through June 15.

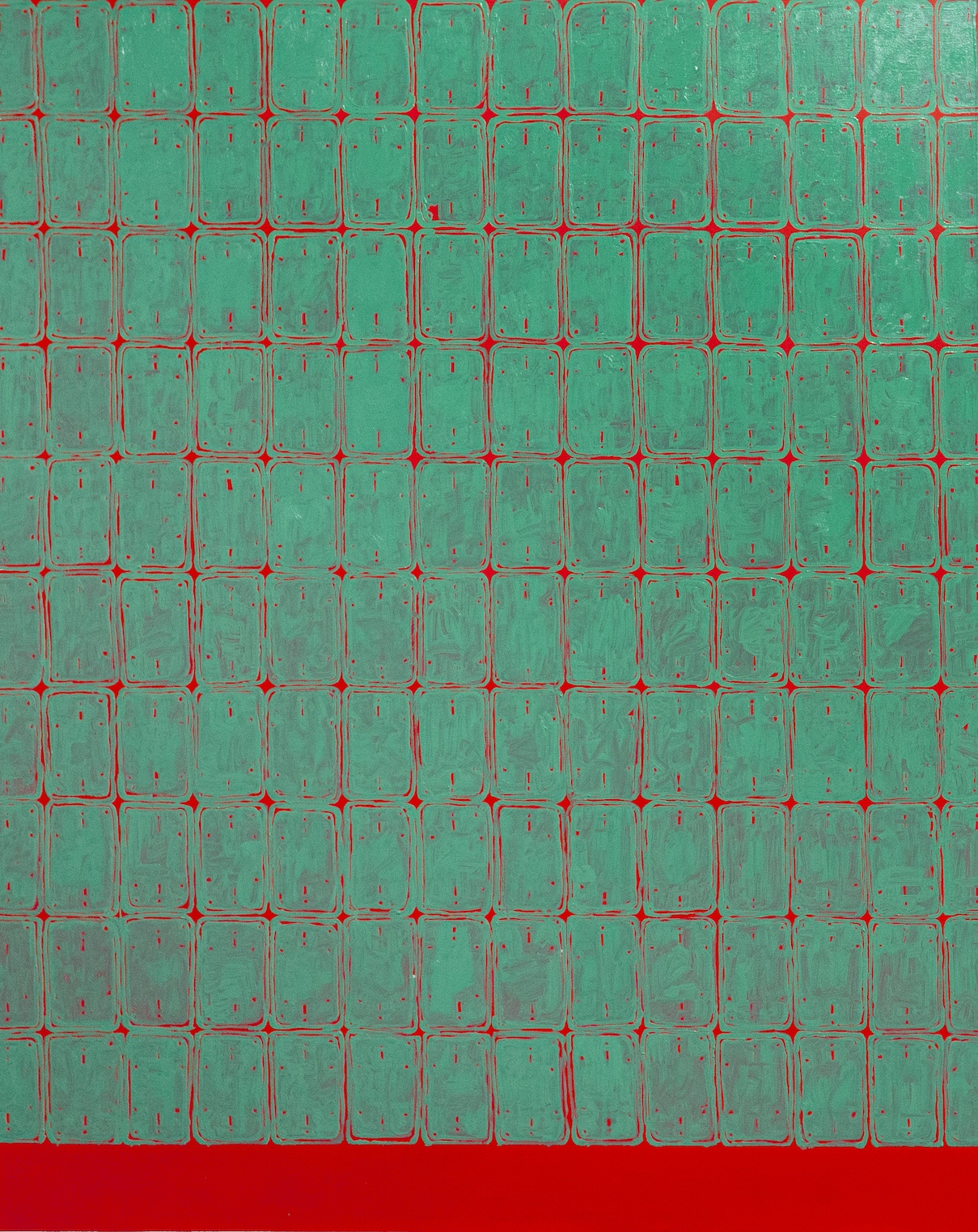

Jaime Pattison, Afterimages, Acrylic and oil on canvas, 72 x 58 1/2 inches, 2024. (Photos courtesy of M Contemporary).

These are sophisticated abstracts — even if Zach Thompson’s striking, half-and-half canvas stars, respectively, Wylie Coyote and Pig-Pen of “Peanuts” fame. Indeed, taken as a whole, the contrast in stylistic approach from one artist to the next is exhilarating.

A downright mesmerizing work is Jaime Pattison’s Afterimages. This is a severe gridwork composition, yet rendered in utterly seductive shades of startling red and aquamarine where the former frames the latter with thin, wispy lines to great visual effect. It’s all rather high concept. Pattison’s playing with what happens when you stare at intense red good and hard, and then close your eyes. The “after image” that pops up leaps from the opposite side of the color spectrum, almost like a photographic negative. And after looking at red, that negative will always be some shade of green.

Each of the 140 aquamarine rectangles within its red frame is a tiny, meticulously constructed abstract in itself, giving the whole a visual depth that, combined with the shock of the red – in this case approaching a neon intensity — is pretty darned transfixing.

In an April interview with the online publication Canvas Rebel, Pattison says she’s been working on “a series of large dichromatic paintings investigating notions of the screen and embodiment. Painting for me is an analog process,” she added, “a process based in the hand, a sifting through digital material to make connections to this time.”

Gallery director Melannie Chard says she’s been following Pattison, who hails from Toronto, since she first saw her work a couple years ago in the annual Student Exhibition at the College for Creative Studies. At the time, Chard says, Pattison was working in a figurative vein, “but now she’s moving into pattern” –- for which we should all be grateful.

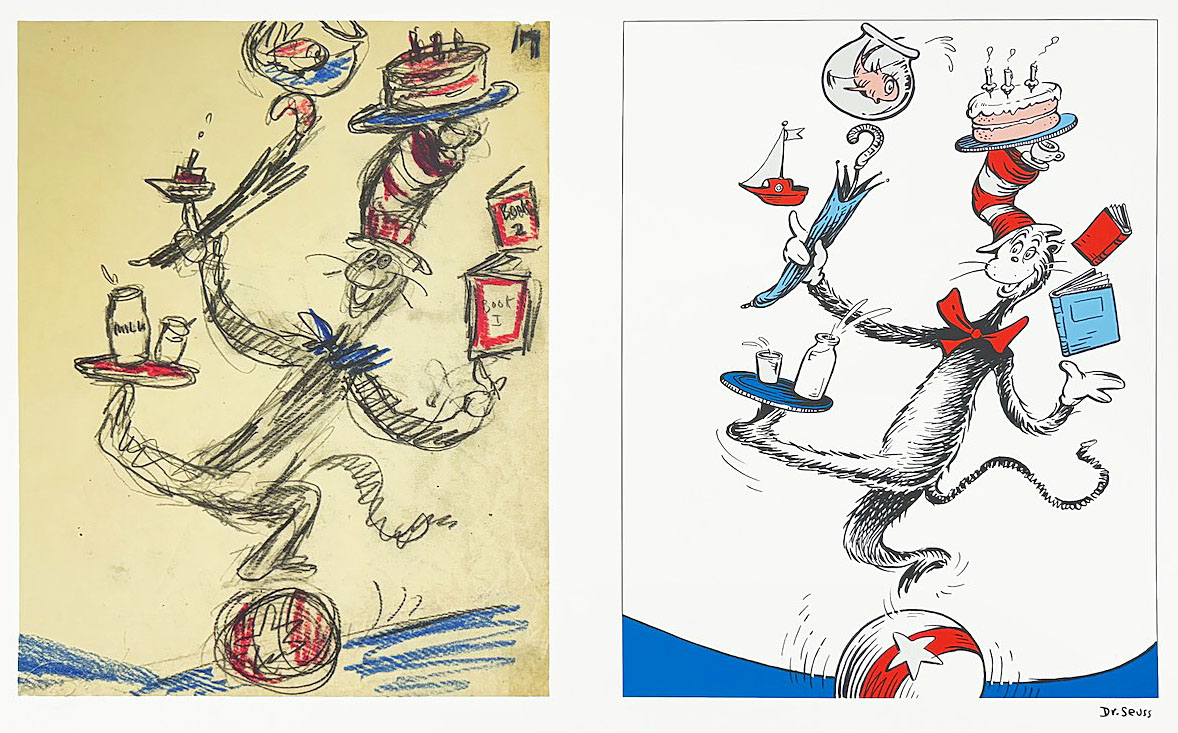

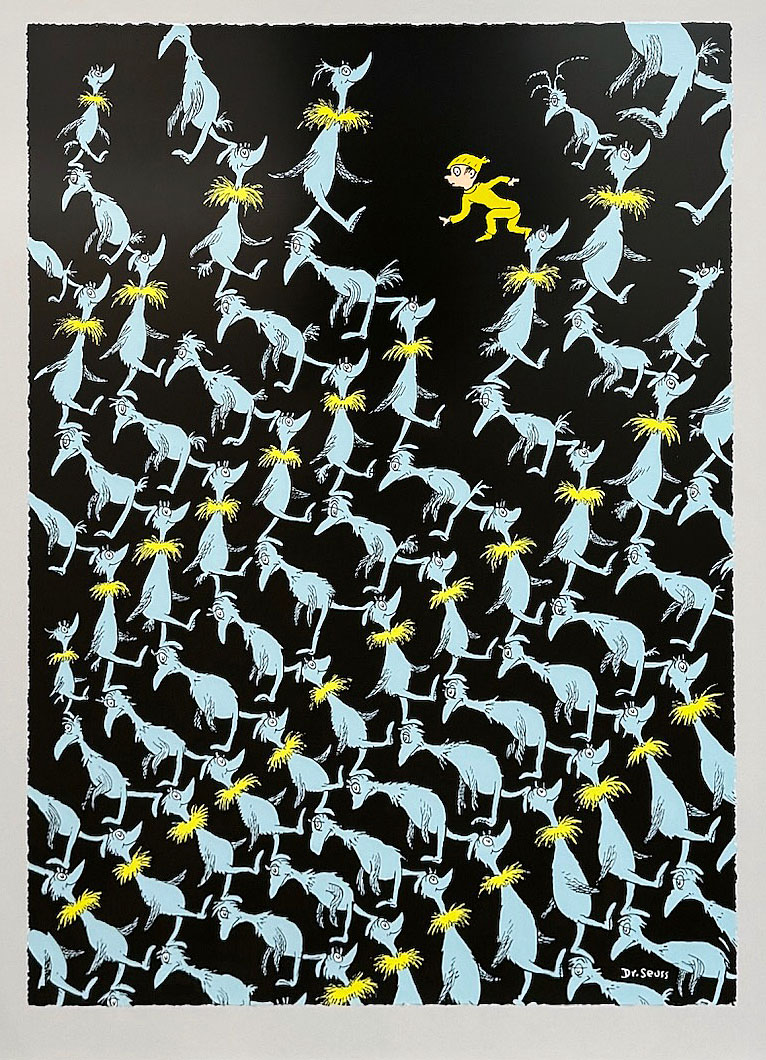

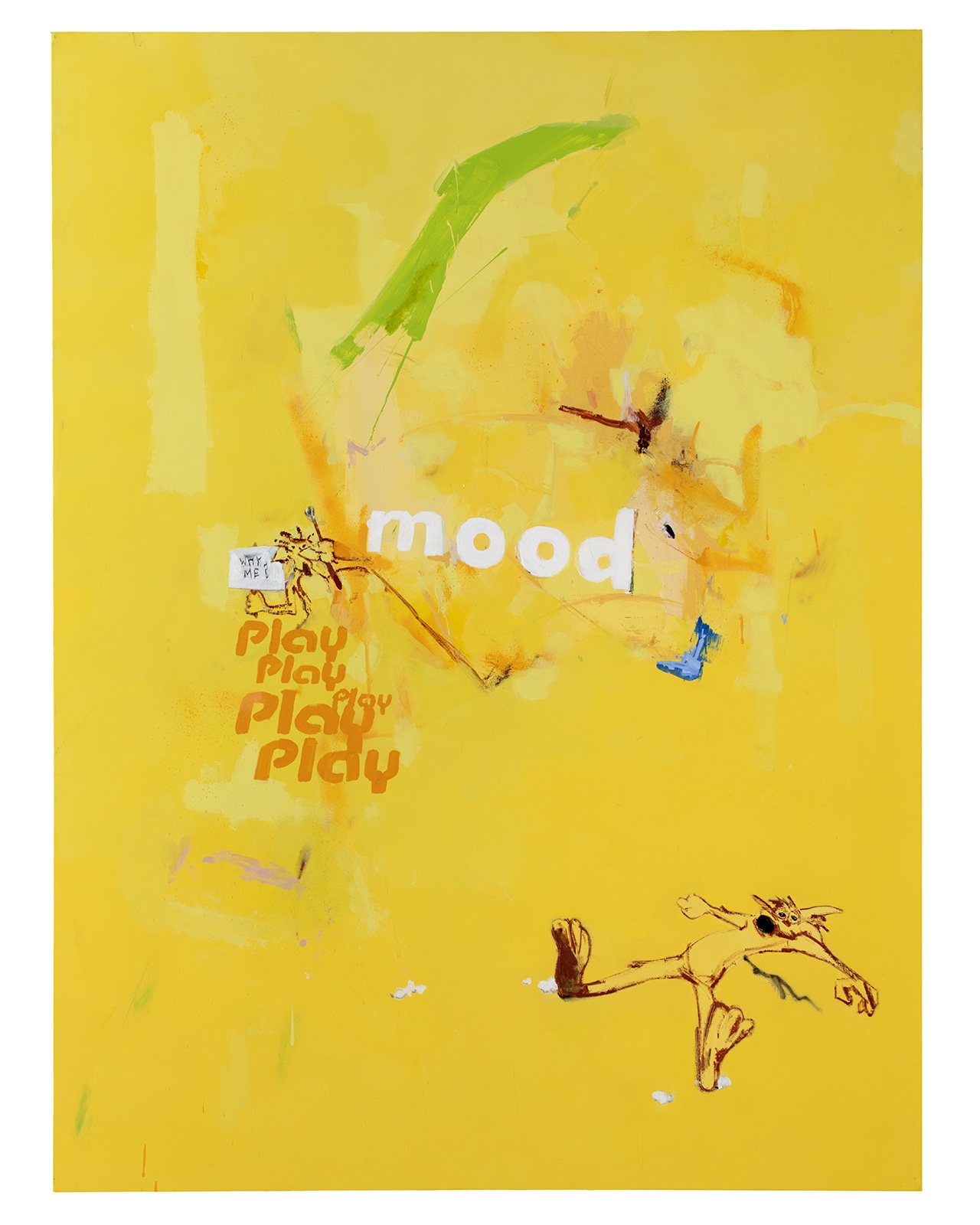

Zach Thompson, The Coyote Has to Eat Too, Oil pigment stick, spray paint, and acrylic on canvas, 48 x 36 inches, 2024.

If Afterimages gives an impression of freehand precision, the left half of Zach Thompson’s canvas, titled The Coyote Has to Eat Too, announces itself with a blast of what appears to be slapdash enthusiasm, with an array of colorful, “careless” blotches scattered across a vivid yellow background.

At once comic and disturbing, the visual focus is our friend Wylie Coyote, lying prone in the bottom-right corner, as if shortly after being obliterated by one of those falling anvils he always seemed to attract like metal filings to a magnet. There’s also a miniature version of Mr. Coyote up above, on the edge of a vortex of swirling hues, holding a teensy sign reading, “Why me?” — a question that can’t help but trigger a laugh, even as it gets to the heart of the human condition.

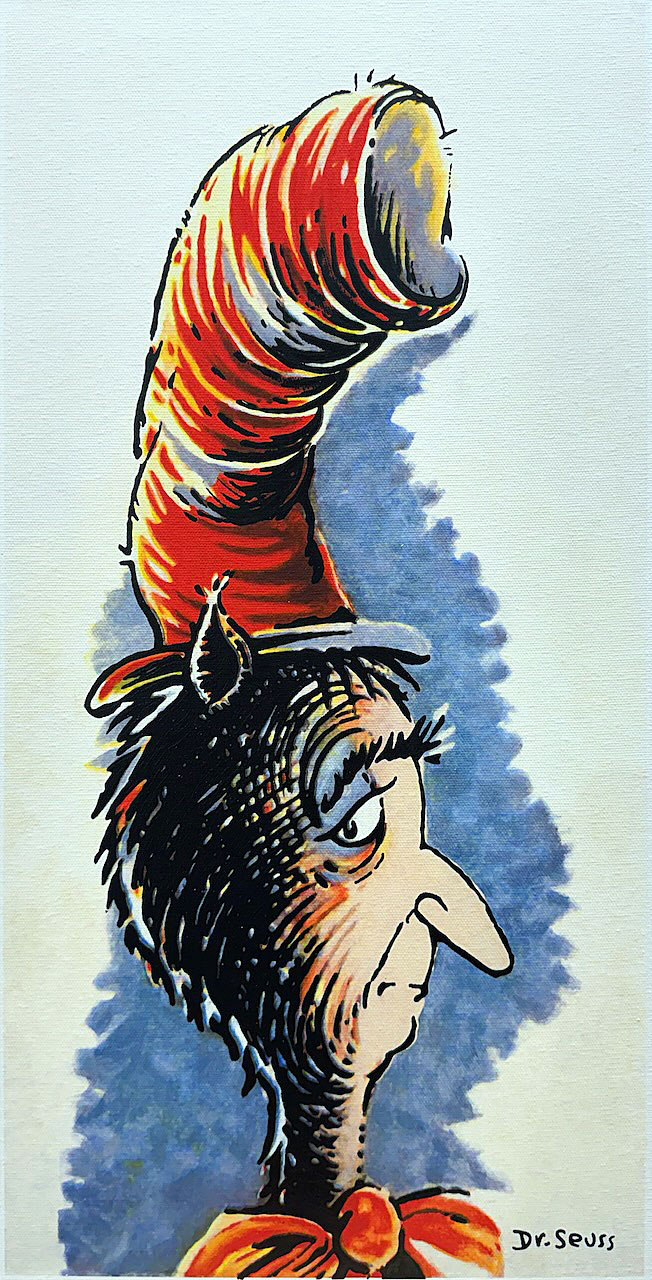

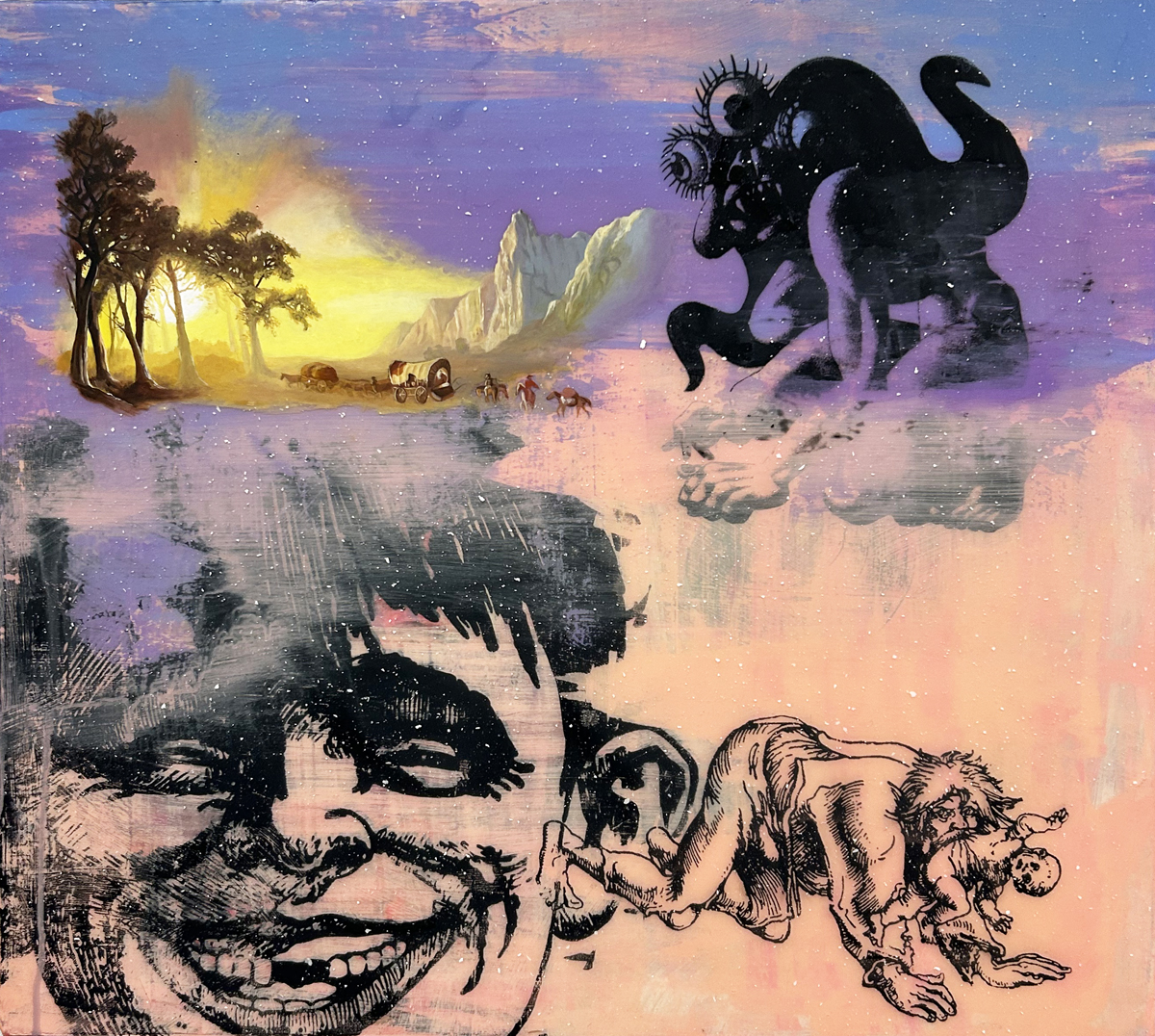

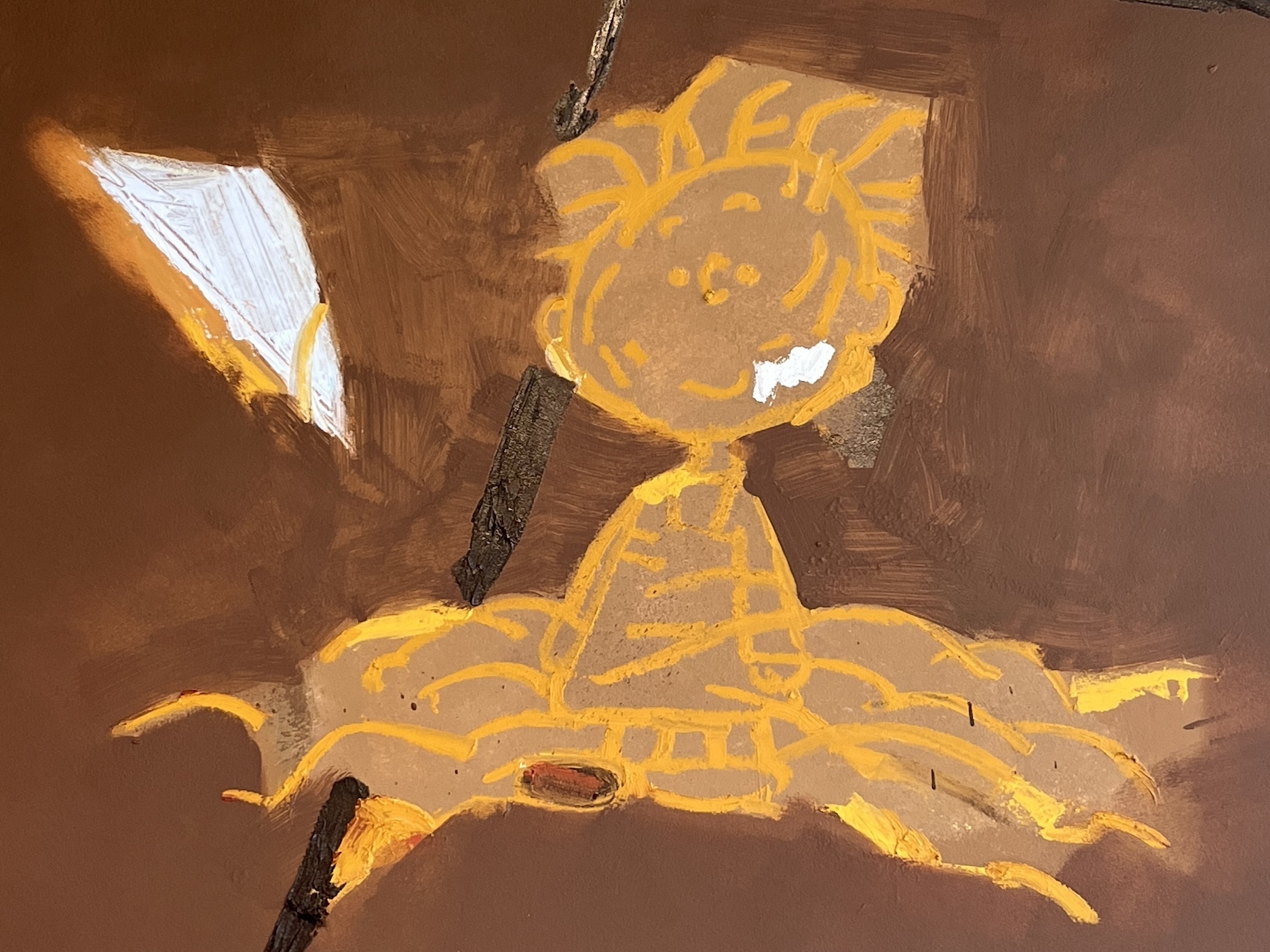

A similar mix of the absurd and the profound characterizes the other half of Thompson’s work, Everything Returns to Dirt, which sports Charles Schulz’s Pig-Pen floating over, of all things, a roosting parrot. Rendered in an array of rich earth tones, including burnt orange, Thompson pulls off another oddball composition that just won’t let go.

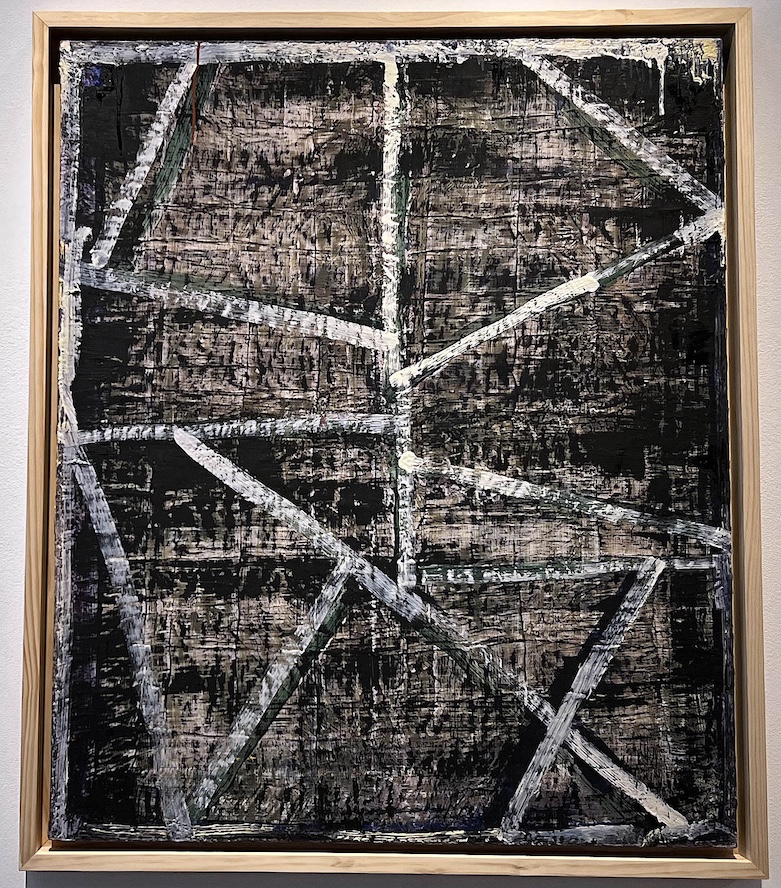

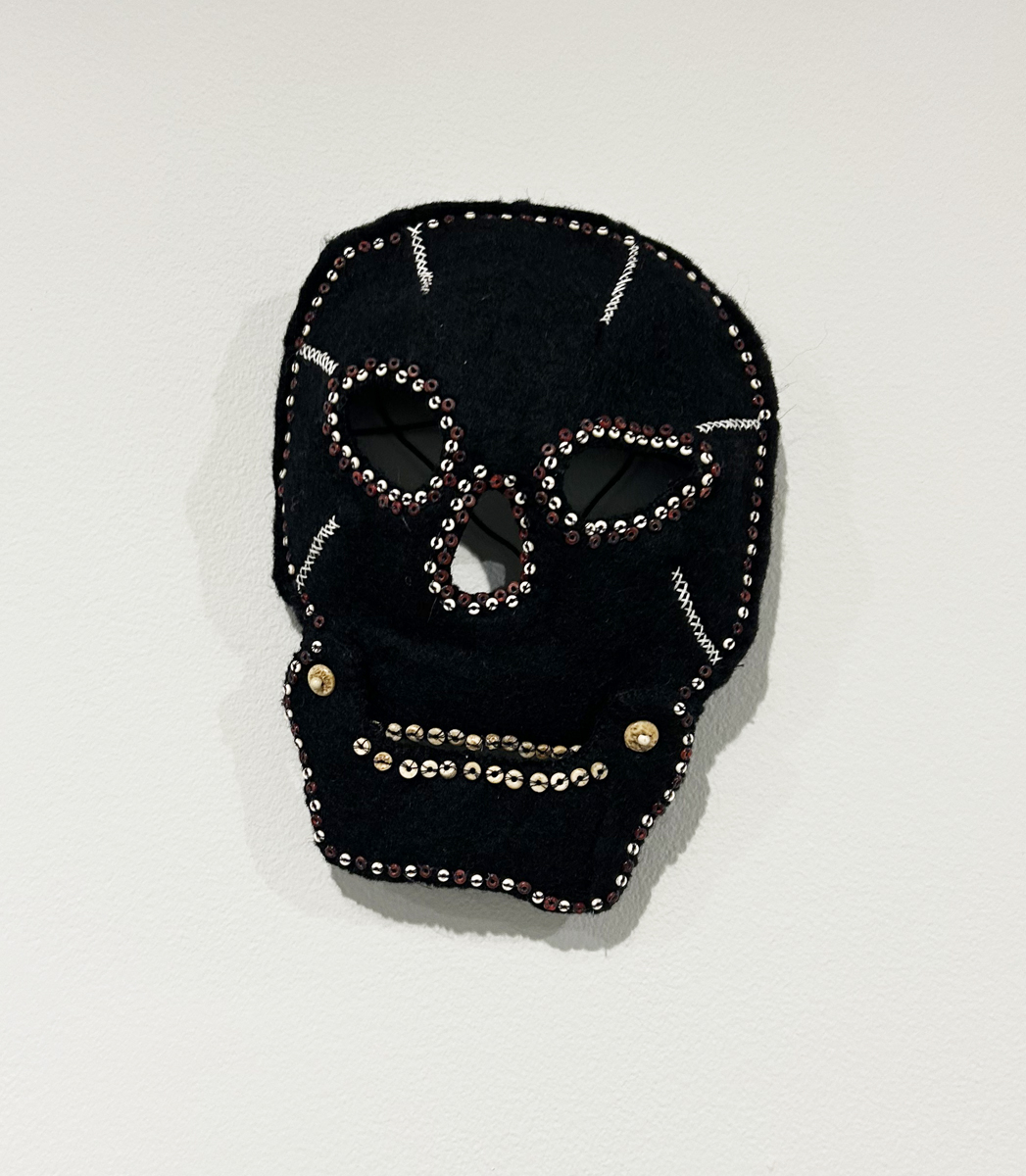

Dino Valdez, Family Values, Acrylic and silver leaf on canvas, 72 x 48 x 1 1/2 inches, 2024.

Ready for something completely different? Painted in black acrylic and elegant silver leaf, Dino Valdez’s Family Values stands out in marvelous counterpoint to the color-rich works surrounding it. An energetic swirl of highly textured black brush strokes, Valdez, formerly exhibitions director at Red Bull House of Art Detroit, manages to achieve a surprising amount of depth that feels downright three-dimensional.

His CV says his recent work focuses on the understanding of violence, conflict, and resolution, which would seem to sum up Family Values, with its barely suppressed fury, rather neatly. Anchoring this visual storm is one perfectly straight white line (although it reads as gray in the image above) that seems to prevent the turbulence from blowing away and dissipating.

Chard says this particular piece is related Valdez’s martial-arts training, and likens the work to that of the classic abstract expressionist Franz Kline, “but not as aggressive. I like Family Values because it almost looks like a dance,” she added, “so expressive and so much energy behind it.”

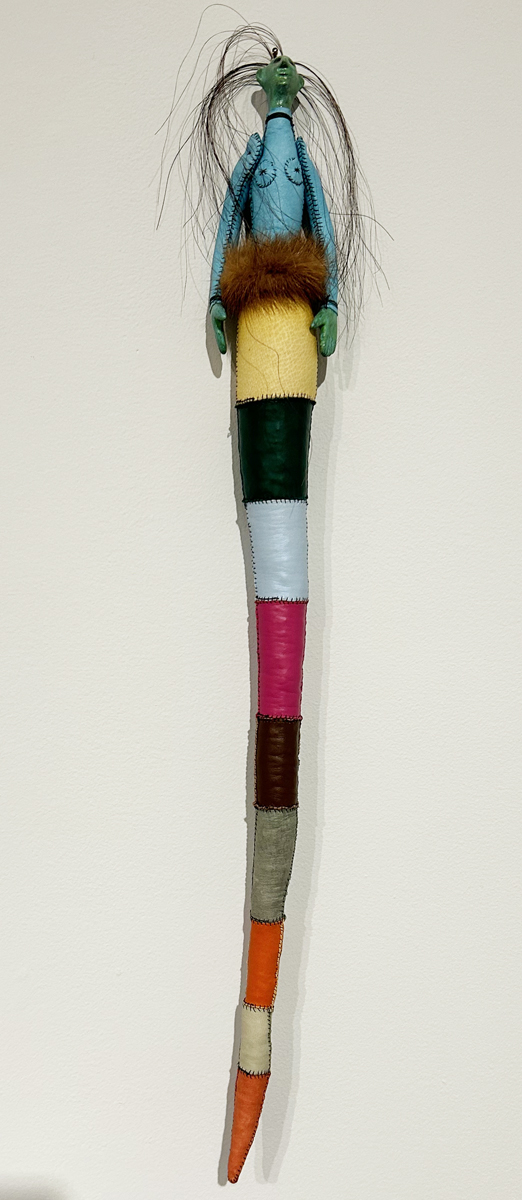

Matt Eaton, Celestial Blanket (Yellow), Aerosol on canvas, 48 x 36 inches, 2024.

Once an energetic presence in Detroit connected with the Library Street Collective, Contra Projects and Red Bull House of Art before his move to the West Coast, Matt Eaton has sketched out a career exploring inventive possibilities in the world of abstraction. Using materials associated with graffiti and graphic arts alike, Eaton’s work has been characterized by a skilled use of color and form.

At M Contemporary, his four identically sized canvases are hung in a square like four panes of a window, through each of which we see what appears to be a piece of fabric fluttering in the air as if hung from a clothesline. Two of these are in rich colors, as with (Yellow) above, while the other two are composed in black and silvery tones. Taken altogether, they make a rich stew.

In a 2016 interview with The Detroit News, Eaton credited the visual universe of the 1980s with steering his artistic instincts in a particular direction. “Growing up at the end of the good punk-rock age,” he said, “there was a lot of hugely influential graphic design at the time. I genuinely would be content if nobody ever saw my art again,” he added. “I’m compelled to make it. It’s more a meditative ritual than a career.”

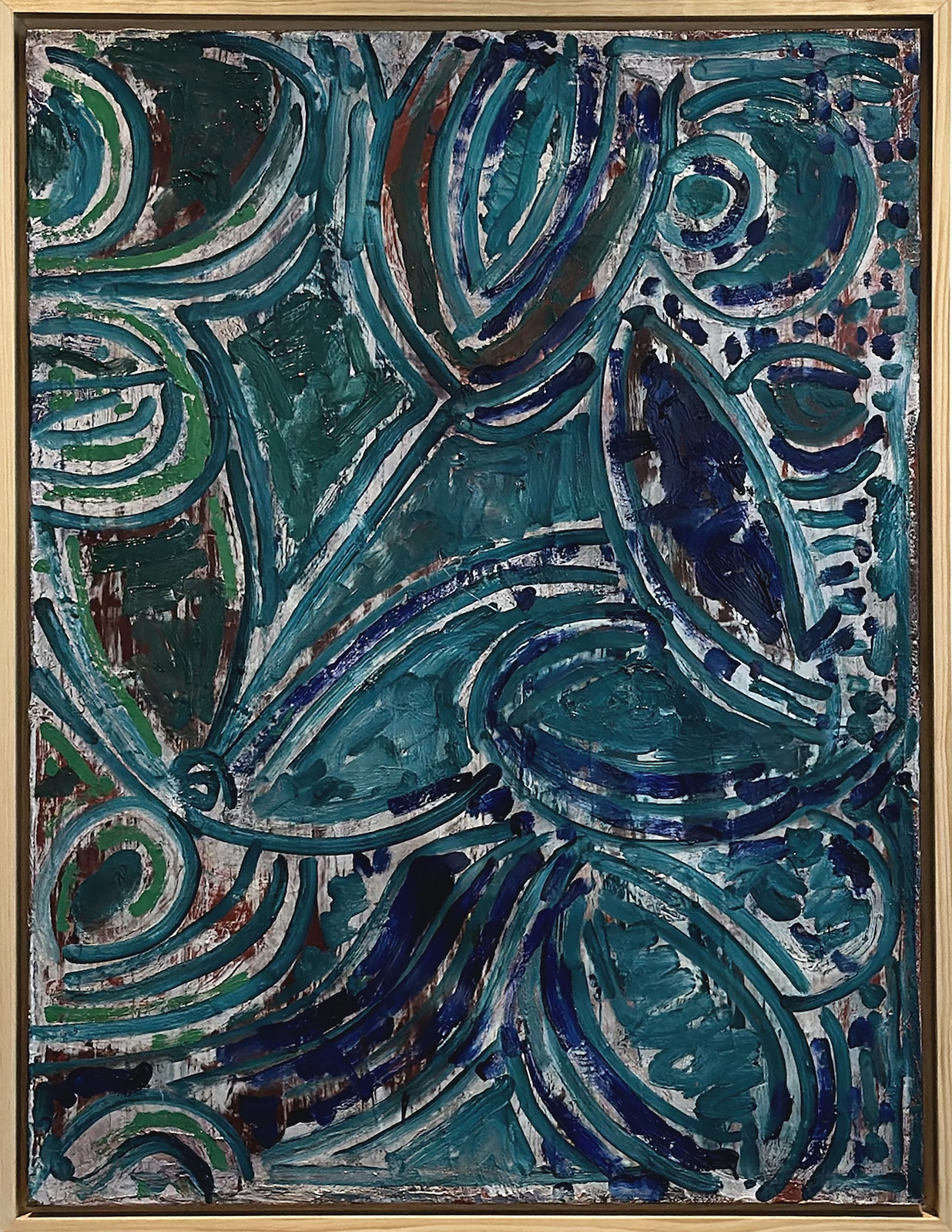

Senghor Reid, Decision at Sundown 6, Acrylic on canvas, 2024.

If Eaton’s blankets mine the potential of simplicity, Senghor Reid’s Decision at Sundown 6 deals with almost stupefying complexity and detail. An explosion of line and squiggle radiating out from a central core near the bottom, it almost reads like – going way out on a limb, here – a visual representation of nuclear fission.

But Chard, who would know, says Decision actually has water as its subject. “It’s one of Senghor’s abstracted water series,” she said. “A lot of people recognize him for portraiture and figurative work, but he has a whole other part of his practice that deals with water, water justice and water rights.” Indeed, anyone who caught last winter’s Skilled Labor: Black Realism in Detroit at the Cranbrook Art Museum might note the resemblance — in line, at least — between Decision at Sundown and the swimming pool in the artist’s large, cheerful Make Way for Tomorrow, that was one of the focal points of that exhibition.

Zach Thompson, Everything Returns to Dirt (detail), Oil pigment stick, spray paint, acrylic, 48 x 36 inches, 2024.

General Rules Do Not Apply will be up at Ferndale’s M Contemporary through June 15.