Dark Matter: Tylonn J. Sawyer at N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art

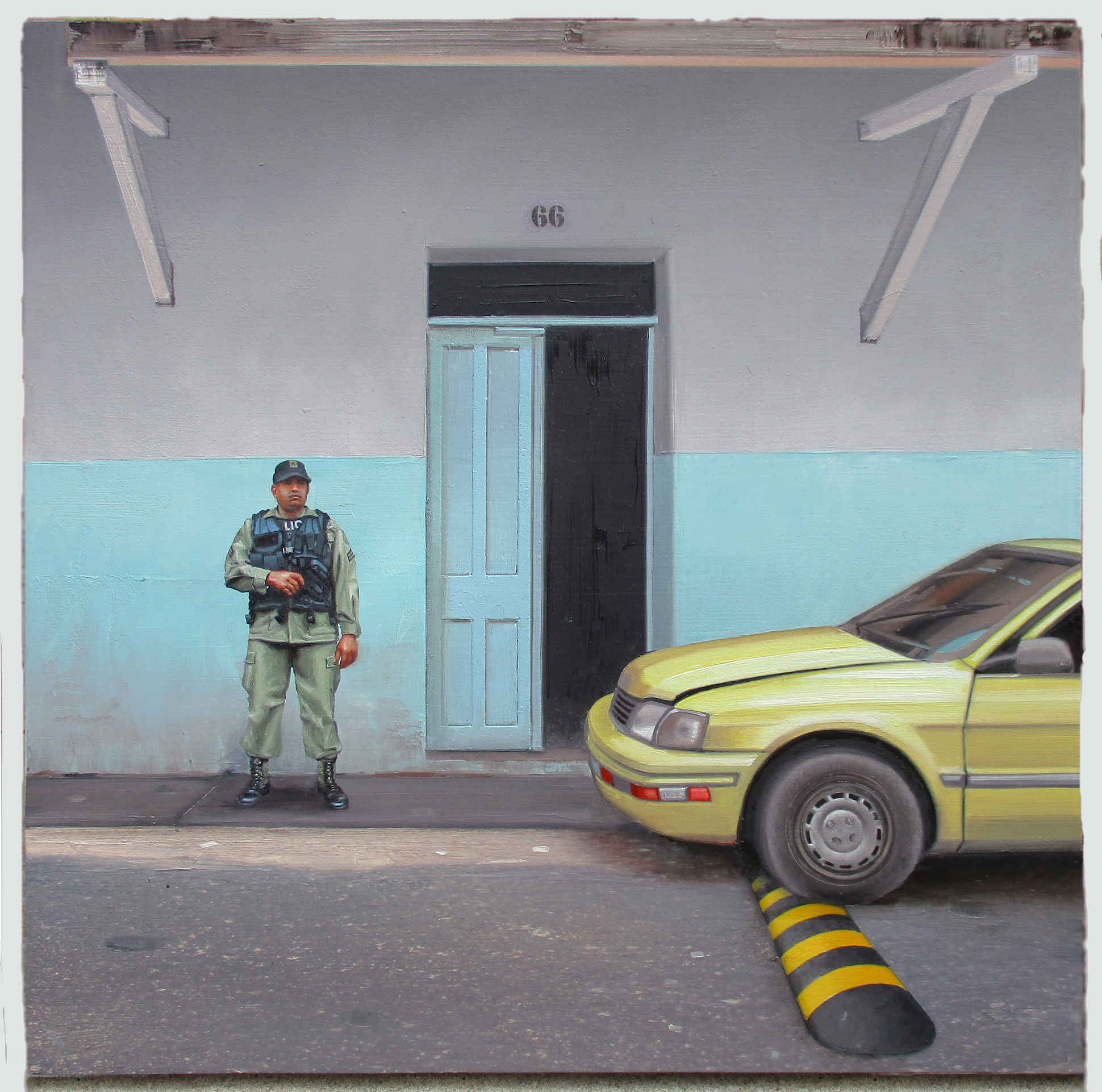

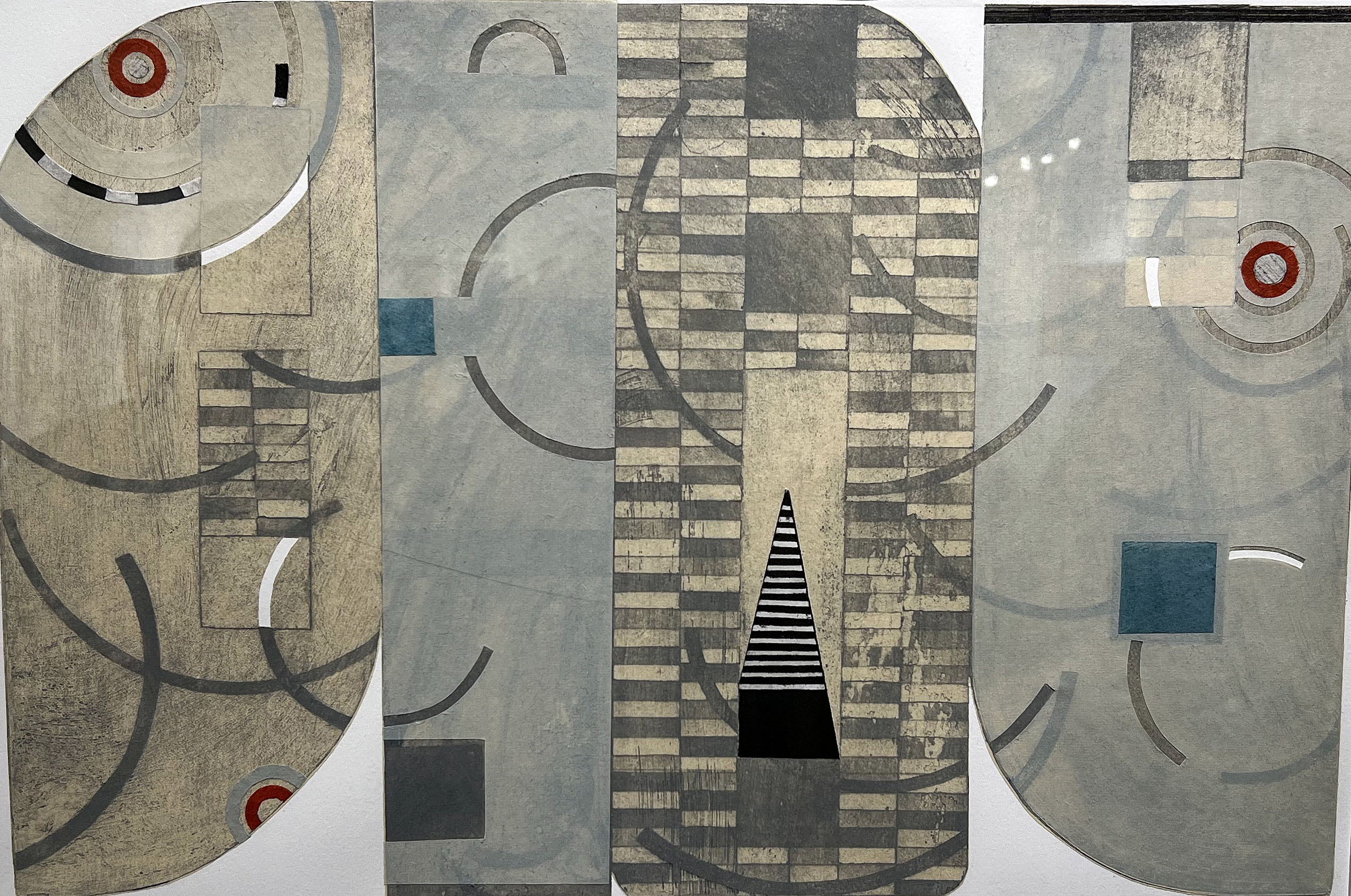

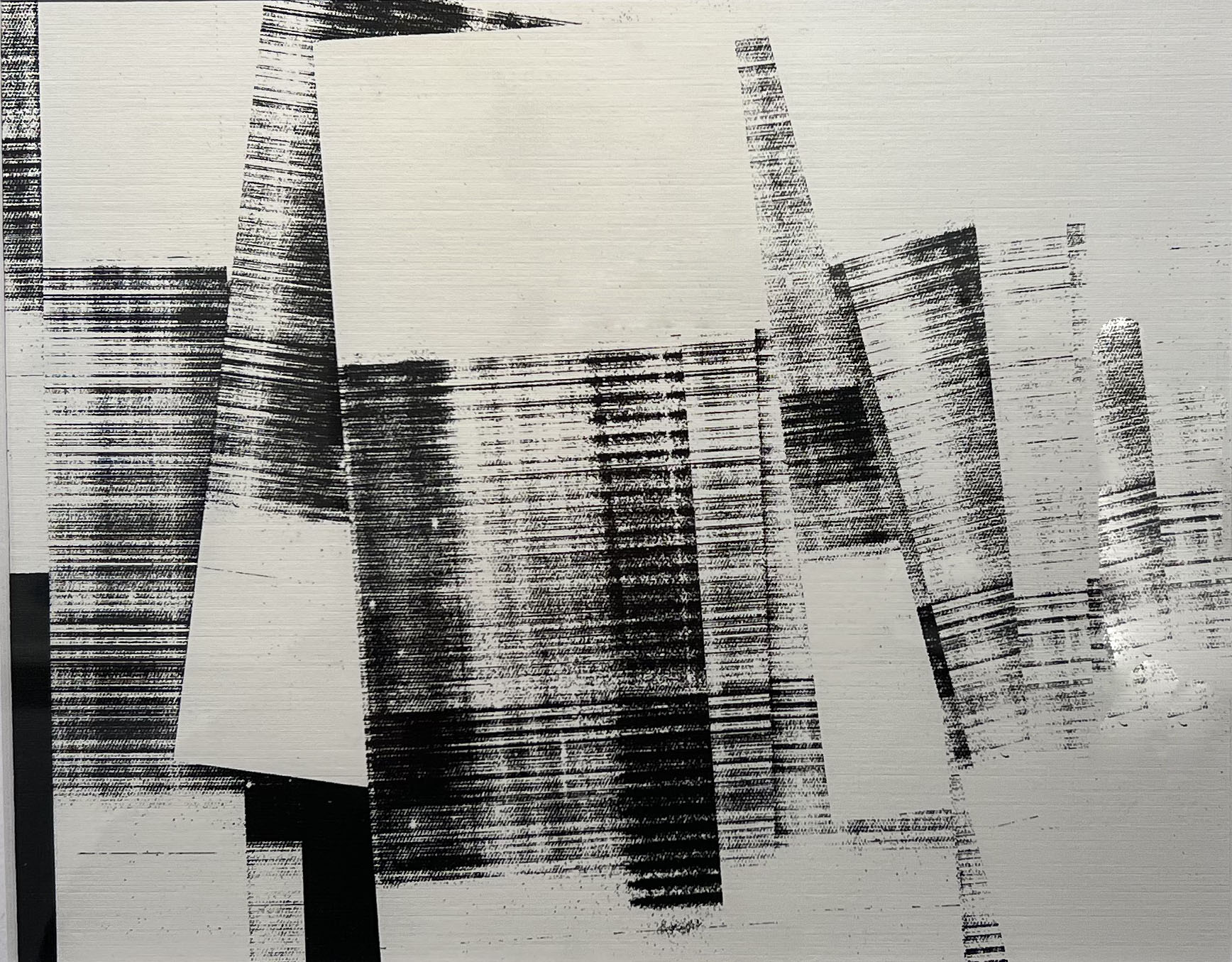

Installation, Tylonn J. Sawyer, Dark Matter, 2023, All photo images by Ashley Cook

The scope of Afrofuturism is vast. It has served as a primary foundation for the creative expression of Black culture for decades before even having a name. The term was coined in 1993 by Mark Dery in his essay Black to the Future and has been used retroactively and moving forward to encompass philosophical applications that depict visions of the future through a Black lens. The dreams and concerns of an Afrofuturist world transcend the real-world struggles of disenfranchised people, particularly those of African descent, in order to imagine a place where their power and contributions are undeniably recognized, appreciated, and valued. Often looped into the genre of science-fiction, it is not uncommon to see images, read stories or hear sounds that seem unusual to us in our contemporary world consumed by oppressive issues of race. Like many Detroit-based artists, the work of Tylonn J. Sawyer actively participates in Afrofuturist conversations surrounding new representations of Black greatness and reclamations of lost agencies. On March 17, 2023, his newest exhibition Dark Matter opened at N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art in Detroit.

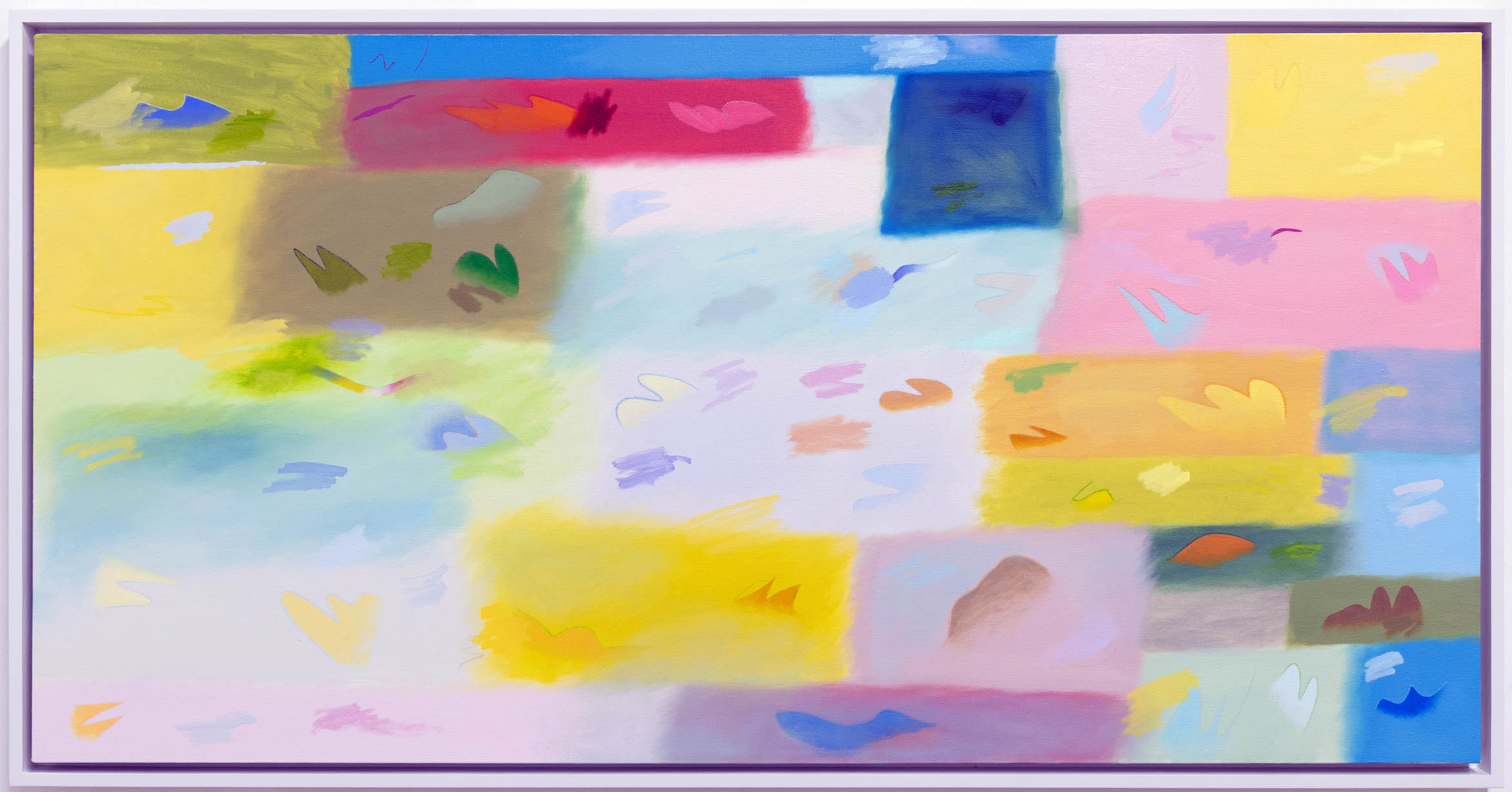

Tylonn J. Sawyer, Embellishment Study: Man on a Black Horse, Charcoal, pastel, and glitter on paper 2022.

Here, some of the genre’s common motifs are revisited in order to remind us that imagining a future and building a world is a practice that requires maintenance. The effort to carve a place where one was previously not allotted is a process that involves looking forward to the future and looking back to the past. The artist exercises this through classical compositions like portraiture on horseback or in Victorian dress. Embellishment Study: Man on a Black Horse and For Small Creatures Such as We the Vastness is Bearable only Through Love position Black figures in roles traditionally held by white royalty. They are large-scale charcoal drawings that evoke other artists like painter Kehinde Wiley who is known for his naturalistic Old-Master-like portraits. This, of course, falls closely in line with Tylonn J. Sawyer’s history as a student at the New York Academy of Art, a school renowned for its figurative program.

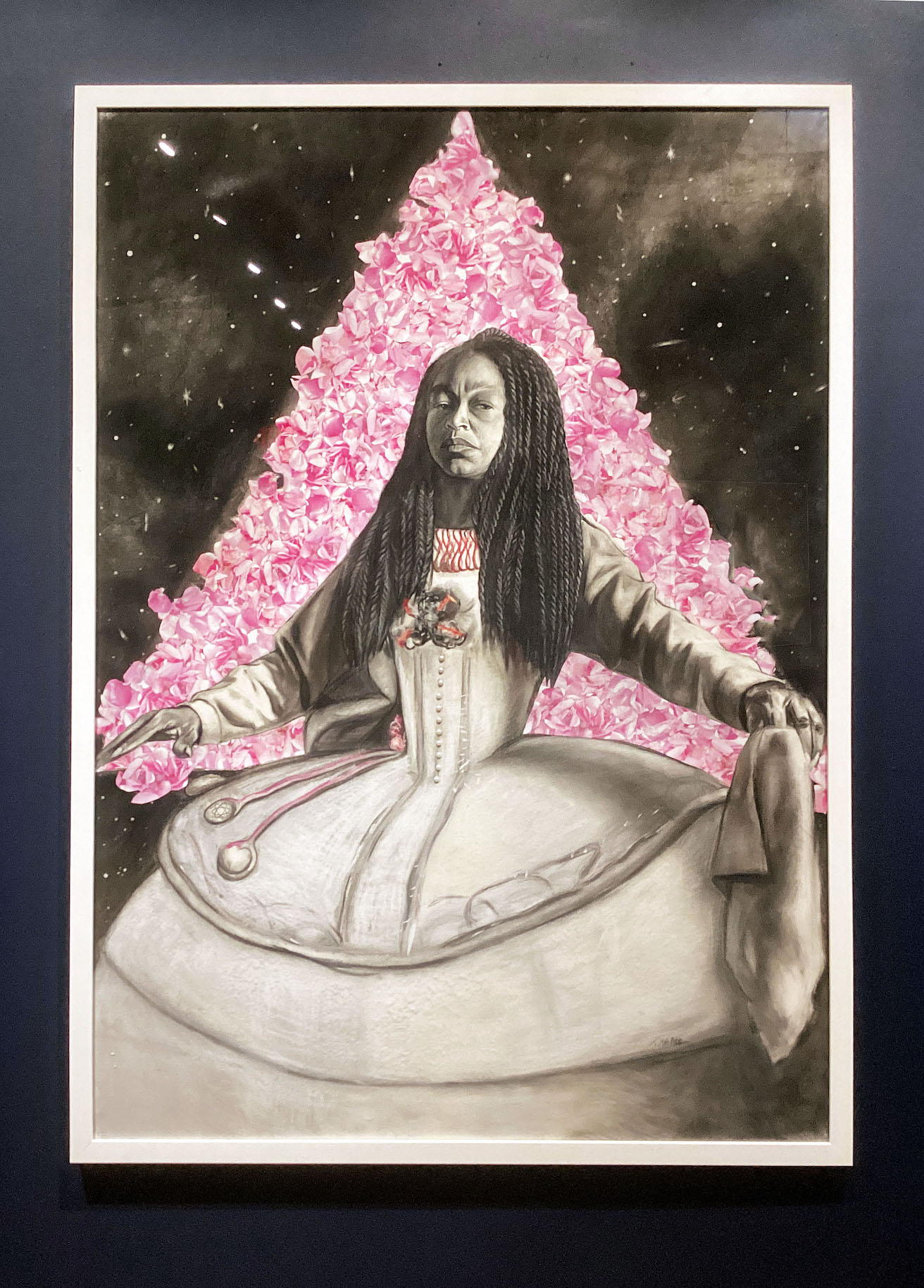

Tylonn J. Sawyer, For Small Creatures Such as We the Vastness is Bearable only Through Love, Charcoal, pastel, pearls, and collage on paper 2022.

Forward-thinking and backward thinking certainly do still take into account contemporary challenges, treating them as critical jumping-off points to open discussions of potential in these world-building efforts. The title Turf War was given to two different oil paintings, each depicting a group of people holding up masks to block their faces. This has been common in Sawyer’s work; many of these masks use the faces of important public figures held often by the artist himself. These paintings in this exhibition are installed directly across from each other, communicating to each other, and challenging each other, white on one side, Black on the other. There is a significance to the hand gestures in each as well; the body language communicates seemingly sinister intent on one side and a fight for power on the other.

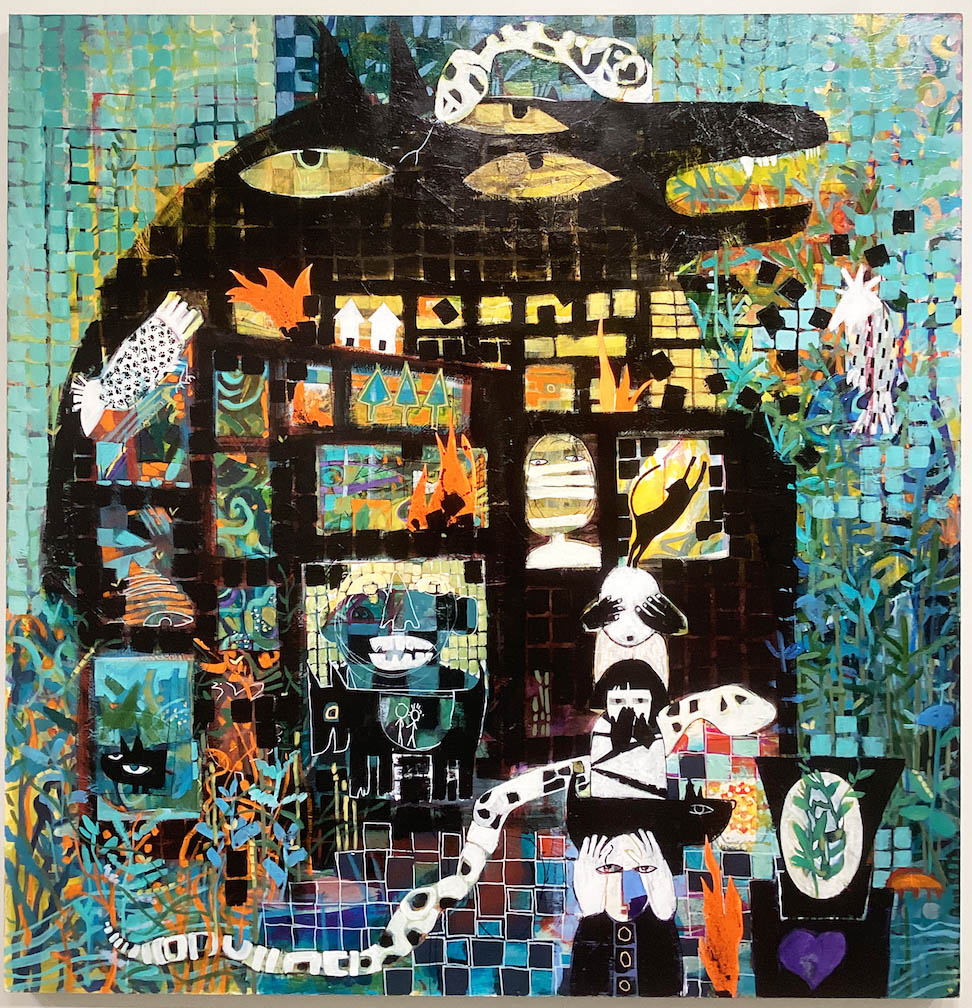

Tylonn J. Sawyer, Matriarch, Charcoal, pastel, and collage on paper 2022.

The use of gold leaf returns us back again to the decorated lifestyle of kings and queens in Moonlight while The Space between Adam’s Reach and God’s Unrequited Love has a background that mirrors the glitter in the aforementioned work of a figure on horseback. These materials and drawing techniques echo visual aesthetics often used in depictions of outer space, uniting the relics of the past with dreams of the future. Matriarch and Royal II are surrounded by the cosmos; there is an homage and dignity being paid to the women in these drawings, their contributions to the world, and the potential they represent. Like Tylonn J. Sawyer, there is and has been for decades, a consistent focus on space travel while imagining a new world and inclusive future for the Black community. From George Clinton and Parliament Funkadelic to Sun Ra to Jeff Mills, the feeling of being “alien” or “other” is widely expressed and explored as a healing mechanism that, on one level, could act as a form of escapism while on another, a tool for empowerment. Dark Matter asks us what is needed to push even further out of our boxes and reach even greater heights. Time and place are some of the most important aspects of our conscious reality to consider when deconstructing and reconstructing our identities, an act that continues to be essential to the resilience of the human spirit.

Dark Matter by Tylonn J. Sawyer is on view until June 19 at N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art, 52 E. Forest Avenue in Detroit. Information: https://nnamdicenter.org/