Elaine L. Jacobs Gallery Installation

The exhibition Confluent, now at the Elaine L. Jacobs Gallery until December 9, combines pieces from the Wayne State University Art Collection with artists creating work in Detroit now, many of whom have current or historical relationships with the university. It’s a reunion of sorts, and quite a party.

Over the past 50 years, Wayne State has been the repository of the University Art Collection, an ever- growing assortment of works by many significant artists who have lived and worked in Detroit. Some were here for a time and left, often going on to success in art scenes on the east and west coasts. Others have stayed put, finding in the frayed edges and vacant spaces of the city a congenial home for their talent. Confluent re-unites artists working here now with a Detroit diaspora.

Jeanne Bieri, The Dance, 2022, army blanket, silver lame’, rayon, wool silk, cotton, army suture cotton from Korean police action lined with repurposed dyed quilt.

Ellen Phelan, Untitled (Shield) 1971, acrylic on cut canvas, photos: K.A. Letts

For the purposes of Confluent, an eclectic group of artists chosen by the collection’s curator, Grace Serra, has been invited to select a work—or several–from the collection that corresponds in some way to their own art practice. Three of the artists, Darryl DeAngelo Terrel, Mary Fortuna and John Rizzo, have chosen to make work specifically for this exhibition. Part of the fun of a visit to the gallery now is to be found in tracing the similarities and contrasts among the artists and their chosen pairings and in making connections of our own.

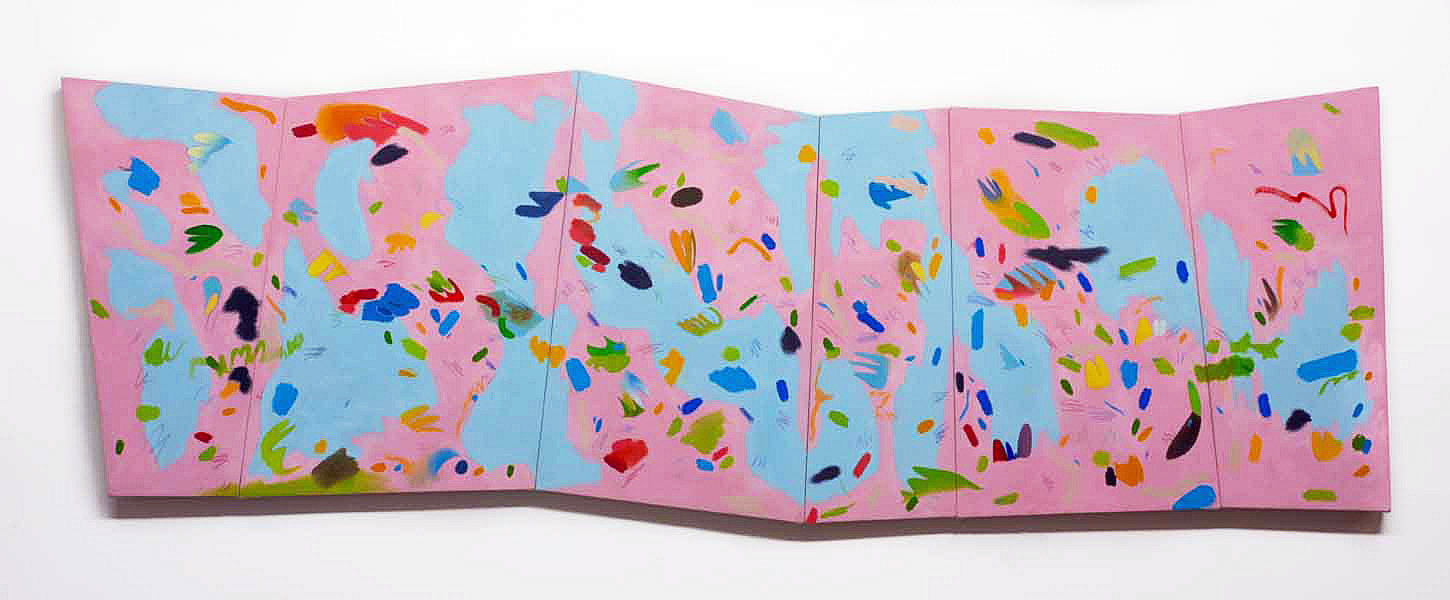

Sandra Osip, Pop-Pop, 2022, fabric, wood, flocking, acrylic paint, foam board, photo K.A. Letts

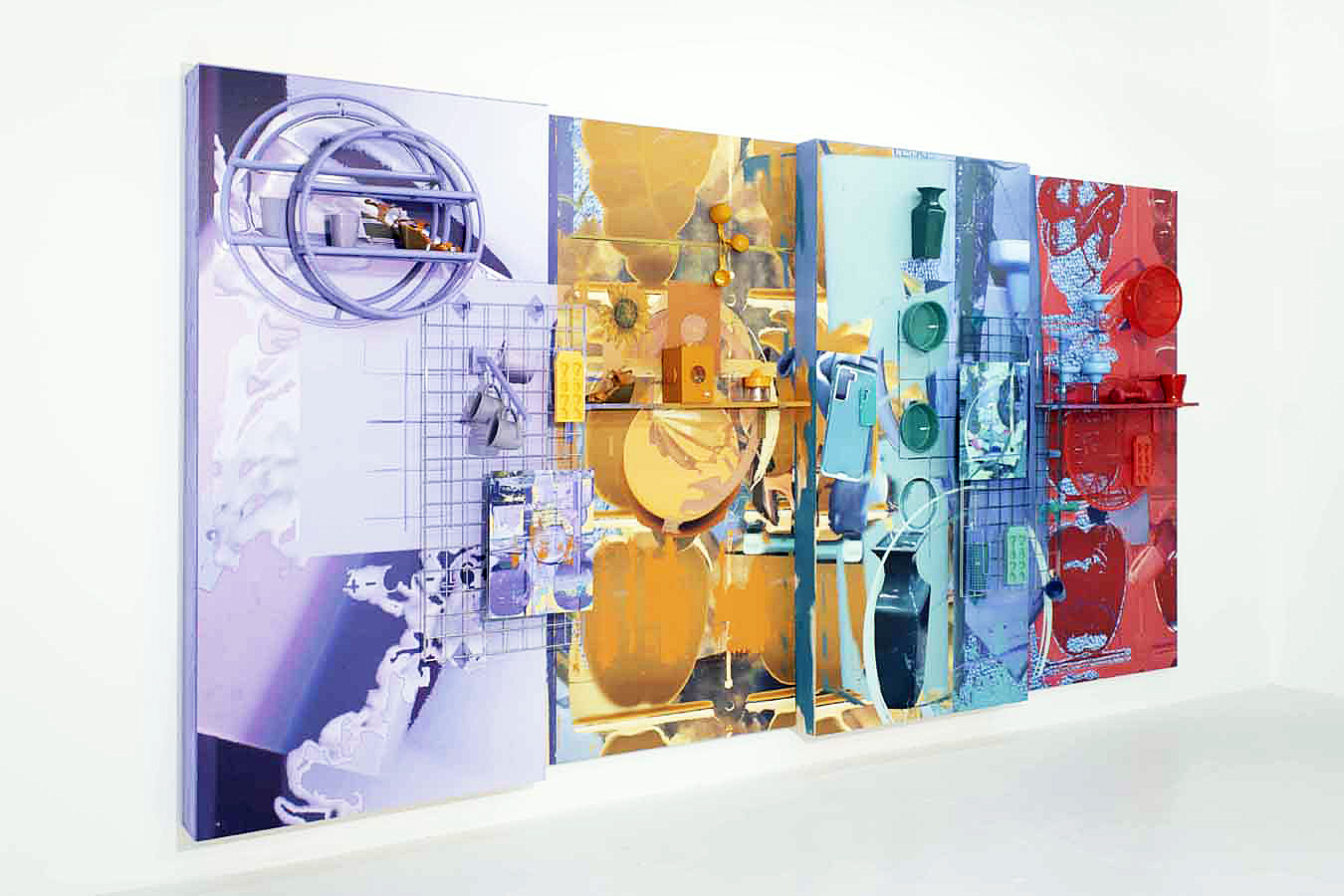

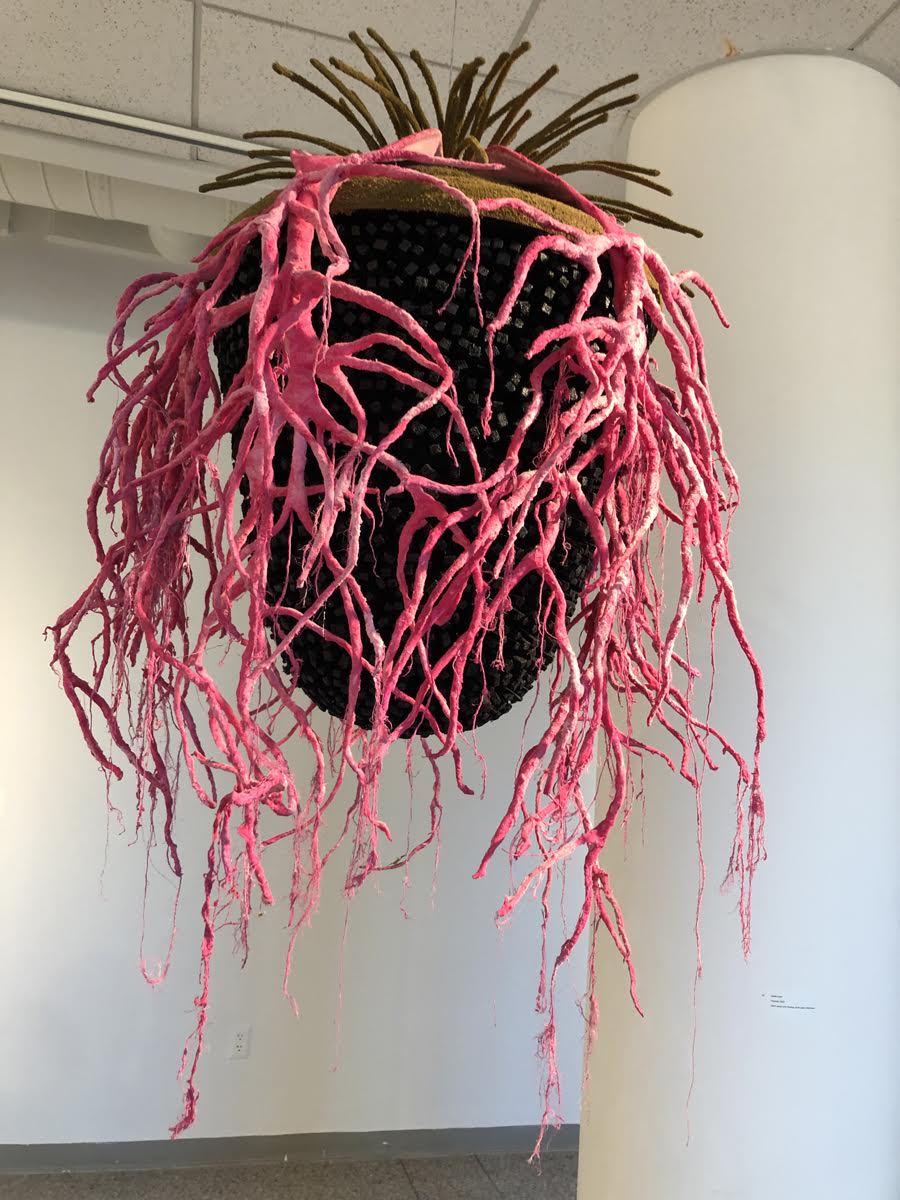

Upon entering the gallery’s main floor, we find Sandra Osip’s colorful vegetal constructions. She has chosen to pair her work with two pieces from the collection, Douglas James’s decorous oil paintings, both from 1973, Stalked Tomatoes and Untitled (Stalked Tomatoes). While the thematic connection is apparent, Osip’s three-dimensional, shocking pink and aggressively feminine Pop-Pop seems also to be engaged in a little side flirtation with Tom Pyrzewski’s nearby louche and bulbous wall-mounted Birth, Re-birth and Moving Parts (2021). Pyrzewski has partnered himself with a beautiful and dignified mixed media wall relief Copernican Communication-Molecular Systems (1983) by Gordon Newton (1948-2019.)

Tom Pyrzewski, Birth, Rebirth and Moving Parts, 2021, mixed media, photo courtesy of the artist.

Gordon Newton Copernican Communications- Molecular Systems, 1983, wood construction, photo: K.A. Letts

Across the gallery, Jeanne Bieri’s improbably beautiful mashup of silver lame’ and old army blankets, The Dance (2022), fits comfortably on the wall with Ellen Phelan’s 1971 Untitled (Shield), a triangular, fringed canvas tapestry.

John Rizzo’s tall, skinny Jenga-like wooden obelisk Ascending (2022) points the way to the upper gallery where more discoveries await. At the top of the stairs, Rizzo–there he is again—modestly frames a tiny piece by Judy Pfaff, Al’s(1974) with his nicely crafted and subtly colored hoop sculpture Contemplative View (2022.)

John Rizzo, Contemplative View, 2022, maple, poplar, paint, lacquer. And Judy Pfaff, Al’s, 1974, wood, tin, oil paint on wood, photo courtesy of John Rizzo

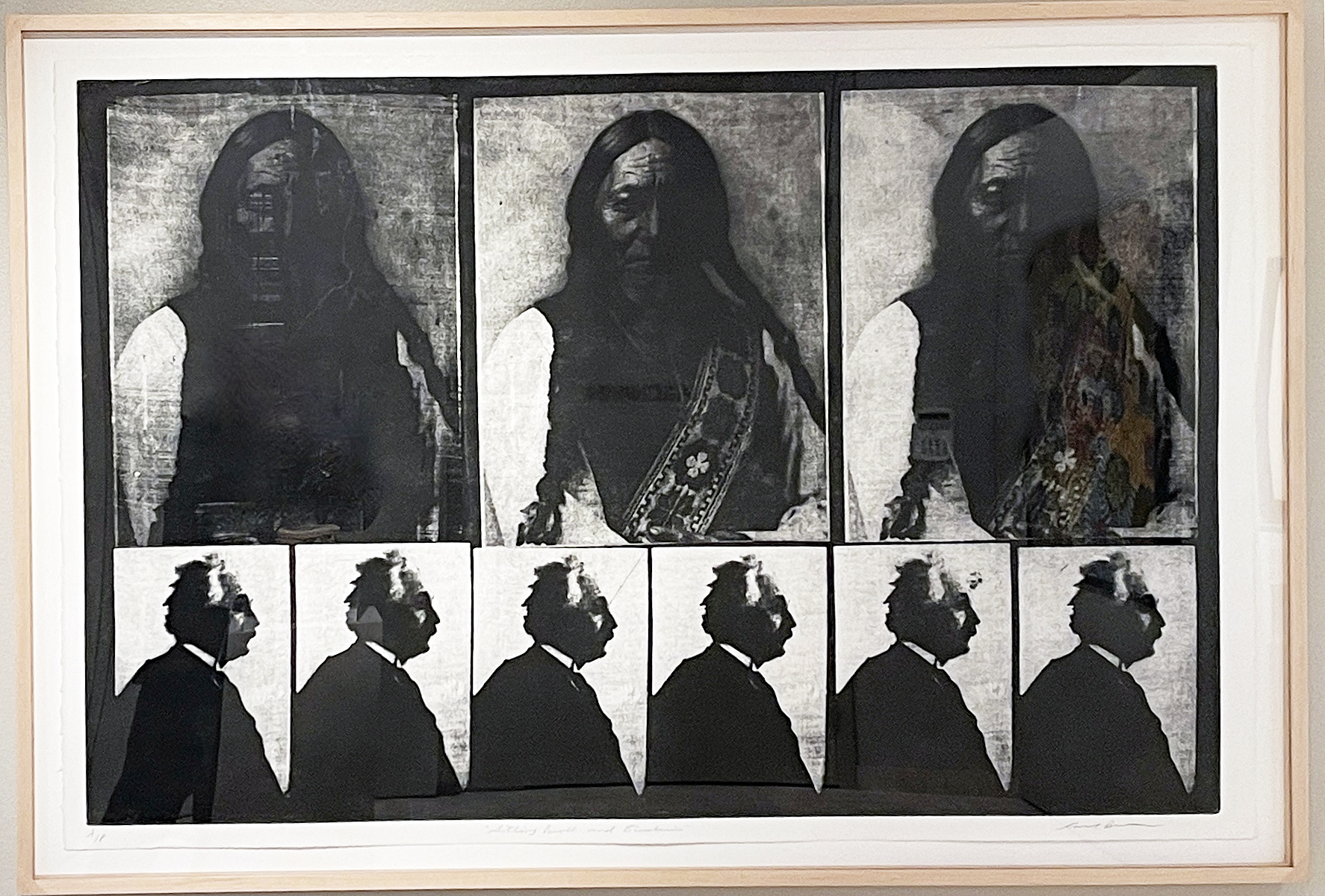

Donita Simpson’s intimate portraits of Detroit’s artists and other cultural figures sit side-by-side with Kurt Novak’s (1945-2019) prankish scanner photographs. The contrast in the bodies of work by these two artists is a reminder of the infinite variety within the medium of photography. Simpson’s dignified portrait of arts writer and Wayne State educator Dennis Nawrocki, backed by his collection of vintage ceramics, Literary Artist Dennis Nawrocki (2017), is a foil to Novak’s comic image of the same writer’s (much younger) face smashed up against the glass of a scanner, Dennis Nawrocki (Detroit Portrait Series, 2003-2005). Both say something true, though different, about the subject.

Donita Simpson, Literary Artist Dennis Nawrocki, 2017, courtesy of artist.

Kurt Novak, Dennis Nawrocki (Detroit Portrait Series), 2003-2005, archival pigment print on cotton.

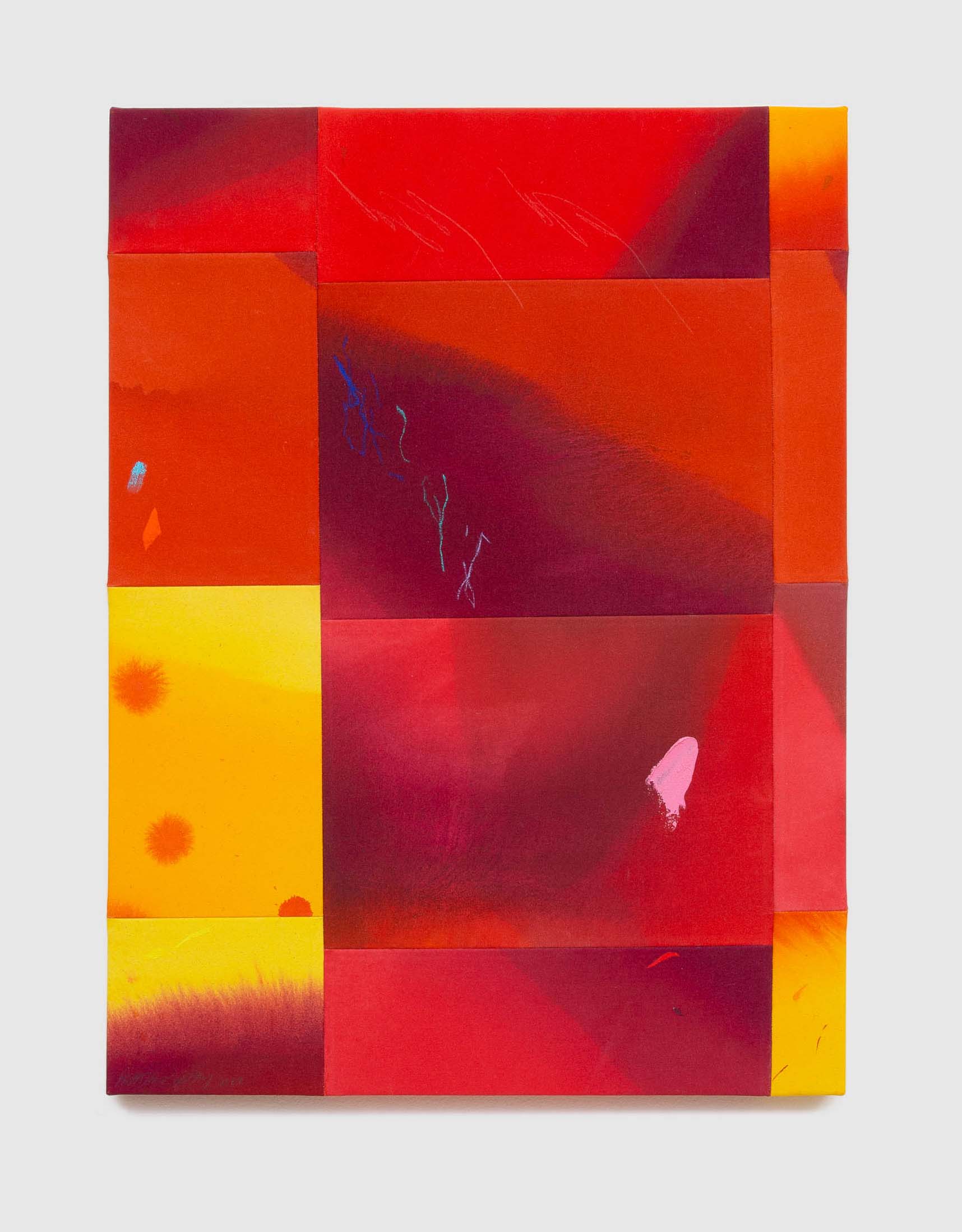

Abstract painters Anita Bates and Marcia Freedman have paired their work with Ron Weill (1945-2019) and Don Willett (1928-1985) respectively, but there is a case to be made that their similarly scaled artworks, installed opposite each other, make for interesting gallery companions on another level. Bates’s painting From Way Up High (2022) is all surface and translucence, shimmering metallics and dense blacks that seem to have arrived on the painting’s surface by some kind of alchemy rather than through the prosaic application of paint. By contrast, Freeman’s painting Cuz(2022) sets up a dark and mysterious fictive space within which a glow like that of a blast furnace pulses.

Anita Bates, From Way Up High, 2022, mixed media, photo courtesy Elaine L Jacob Gallery

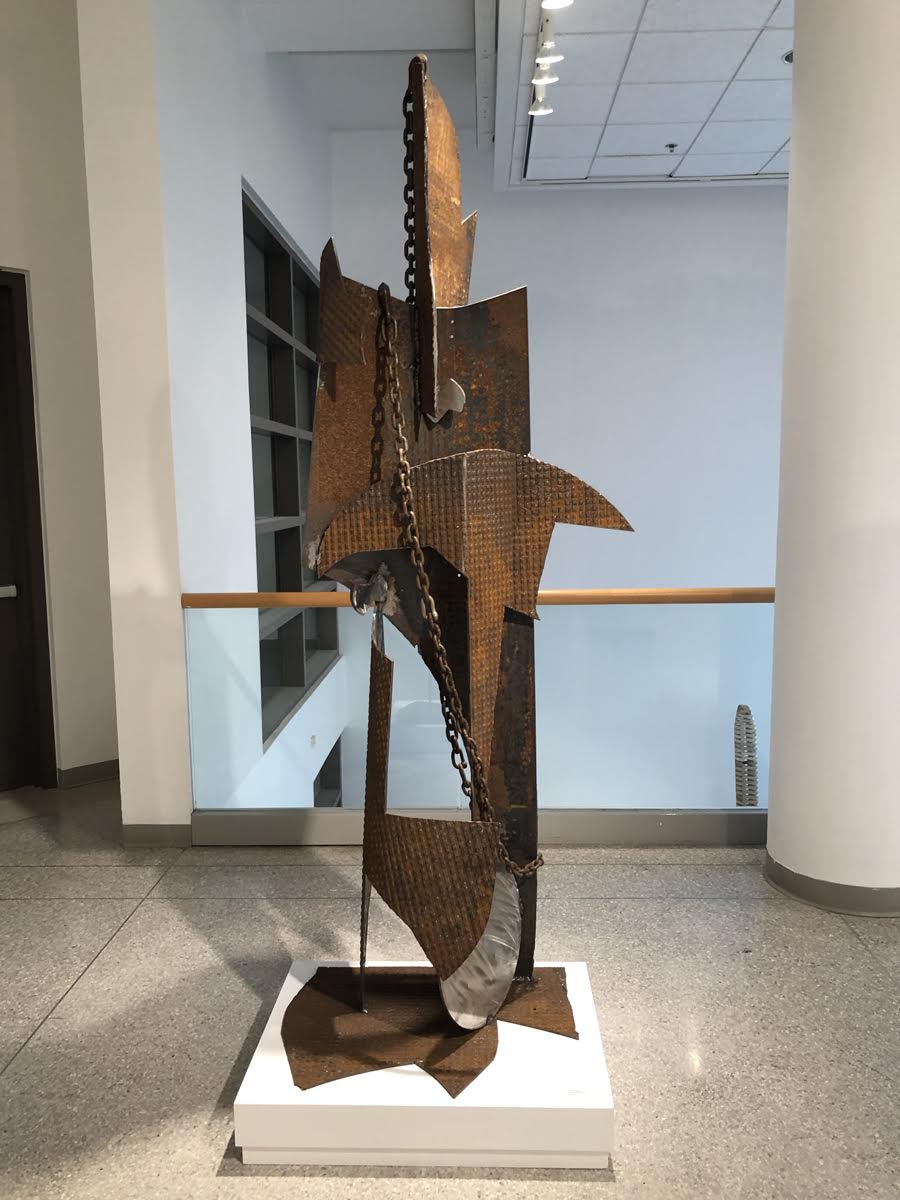

Around the corner, a monumental, welded steel sculpture Sentinel for Martin (2022) by M. Saffell Gardner, is paired with a small painted steel saw blade Untitled: Happy Birthday Jim (1973) by John Egner (1940-2021). Egner was a teacher and mentor to Gardner and in spite of the disparity in scale, the two pieces share a sense of connection with the larger community that resonates.

Marcia Freedman, Cuz, 2012, oil on canvas, photo: K.A. Letts

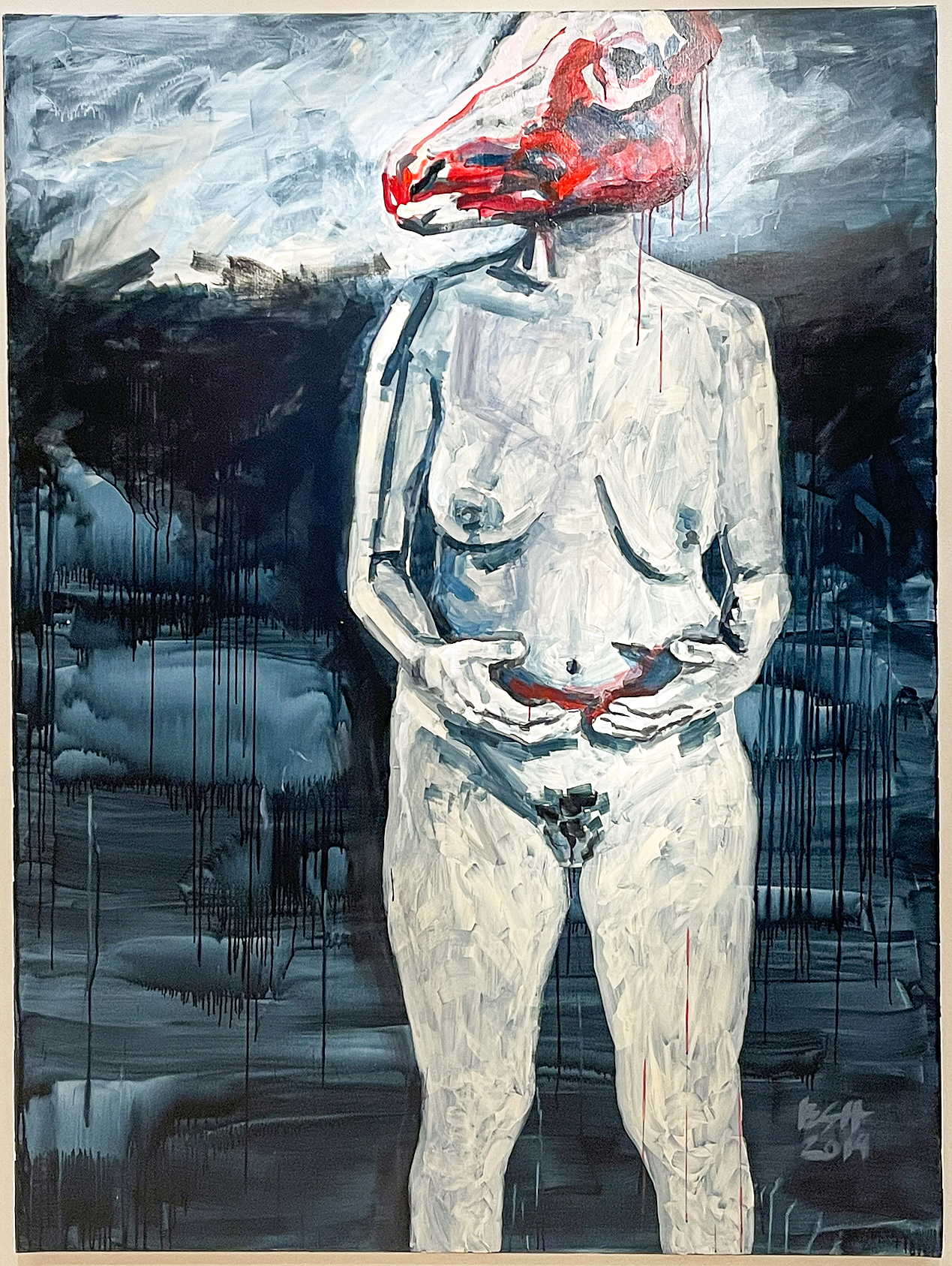

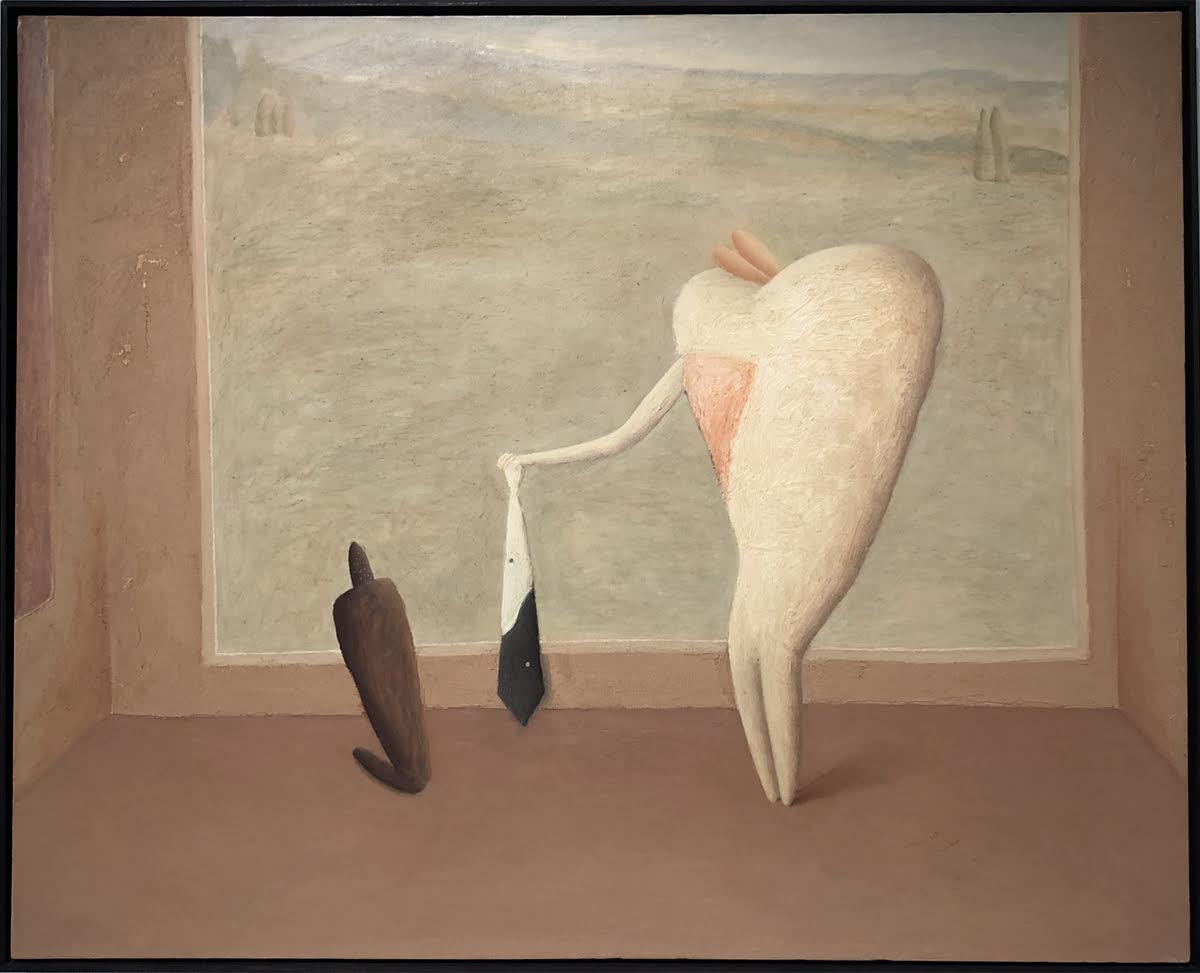

Three humorously improvisational assemblages by Mariam Ezzat, Nothing Lasts Forever, Saint Sophia; Nothing Lasts forever Except you: Animus Possession and Nothing Lasts Forever Except You: Earth Angel (2022) play well with The Offering (1983) an arresting early painting of comic menace by Brenda Goodman. The work of these two artists, though created 40 years apart, expresses a spirit of irreverence and experimentation—an attitude of what-the-hell and why not?–that is very Detroit.

Brenda Goodman, The Offering, 1983, oil on canvas, courtesy of Elaine L. Jacob Galley.

Mariam Ezzat, Nothing Lasts Forever, Saint Sophia; Nothing Lasts Forever, Except you: Animus Possession; Nothing Lasts Forever, Except You: Earth Angel (all 2022) mixed media.

The artworks from the University Collection, shown alongside the recent output of Detroit artists, begins to bring the unique creative spirit of the city into focus–improvisational and often cheeky, but serious and hard-working too. As Curator Grace Serra says in her exhibition statement, “The collection is special and unique; I believe it is the only collection that directly mirrors the diverse styles and artists of the community, capturing the depth and breadth of the cultural landscape.” Her bold claim is backed up by the diversity and quality of the work in Confluent and it’s a powerful argument for keeping the collection on permanent public display to provide context and inspiration for artists working in Detroit now, while honoring and preserving the city’s shared art history.

Saffell Gardner, Sentinel for Martin, 2022, welded steel.

John Egner, Untitled (Happy Birthday Jim) 1973, oil on the circular saw blade, photos: K.A. Letts

Artists in Confluent:

Anita Bates, Jeanne Bieri, Darryl Deangelo Terrell, Sergio De Giusti, Mariam Ezzat, Mary Fortuna, Marcia Freedman, M. Saffell Gardner, Laura Makar, Sandra Osip, Tom Pyrzewski, John Rizzo, Donita Simpson, Diane Carr, John Egner, Brenda Goodman, Susan Hauptman, Douglas James, Gordon Newton, Kurt Novak, Judy Pfaff, Ellen Phelan, Robert Quigley, Ron Weil, Robert Wilbert, Don Willett

The exhibition Confluent, now at the WSU’s Elaine L. Jacobs Gallery until December 9, 2022