Larry Cressman, Installation, Fieldwork, All images courtesy of K.Oss gallery

Larry Cressman: Fieldwork Exhibition at K.Oss Contemporary Art

Like a straightforward black and white film liberated from the distractions of color and spectacle, the “Larry Cressman: Fieldwork” exhibition at K.Oss Contemporary Art, given its elemental hues, might have been titled “Black and White.” Upon entering the snug, spartan gallery, Cressman’s reductive, purified palette, content (“fieldwork”), and elemental format (rectangles abound) immediately cue visitors: striking displays lie ahead. Whether framed and portable or installational (bare branches hovering an inch or two in front of a wall), the dozen and a half compositions, essentially shallow reliefs, proffer a bevy of intricate, engaging configurations.

Birthed, as they are, from excursions into the fields near his home and studio, Cressman collects the raspberry cane, dogbane, and dried daylily stalks that initiate the process of gestation. Then, as the slender, fragile branches and twigs are joined one to another with nearly invisible wires, dusted with graphite, and mounted on the walls with thin, sturdy pins, his “linear landscapes” fill out and mature. As many as 200 or more conjoined branches may be necessary to scale up to an easel size armature.

Larry Cressman, On Line, raspberry cane, powdered graphite, matte medium, wire, pins, 60 x 90 x 12 inches, 2017-18

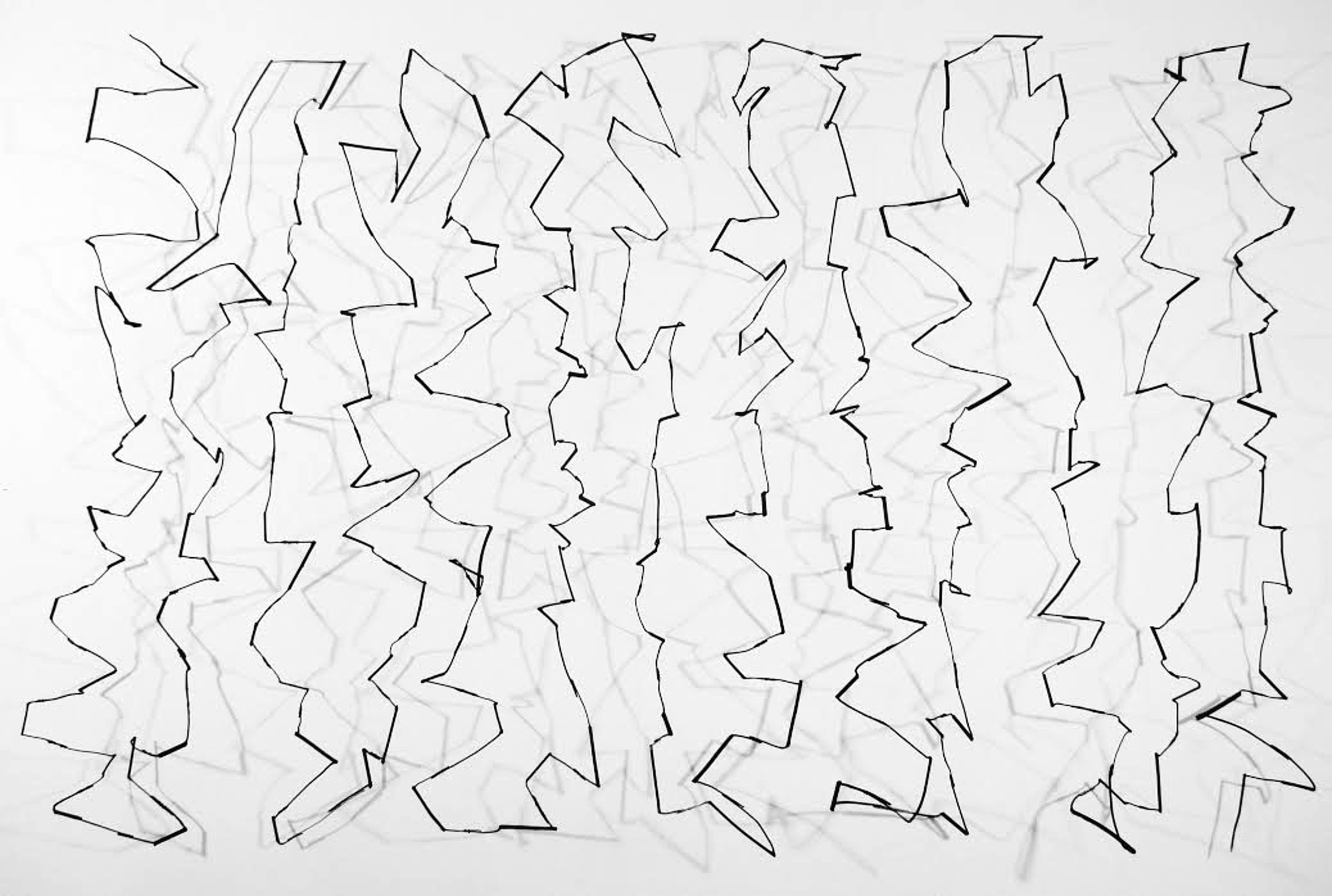

In One Line, for instance, a zig-zagging single line, fabricated from a gross of raspberry canes, begins or terminates at upper left or lower right. Swiftly, it carries the eye, body, and psyche some five feet across (and to heights of nine feet) along the jerky, twitchy pathway, like a marathon runner, rock climber, or artist. Further enhancing the journey are the myriad shadows thrown upon the wall that seem to double or triple the length and aesthetic thrum of the journey. Such adrenal feats, like a host of durational endeavors, literal or figurative, both exhaust and exhilarate participants.

Larry Cressman, Podcast IV, dogbane with seedpods, powdered graphite, matte medium, wire, pins, 60 x 36 x 19 inches, 2018

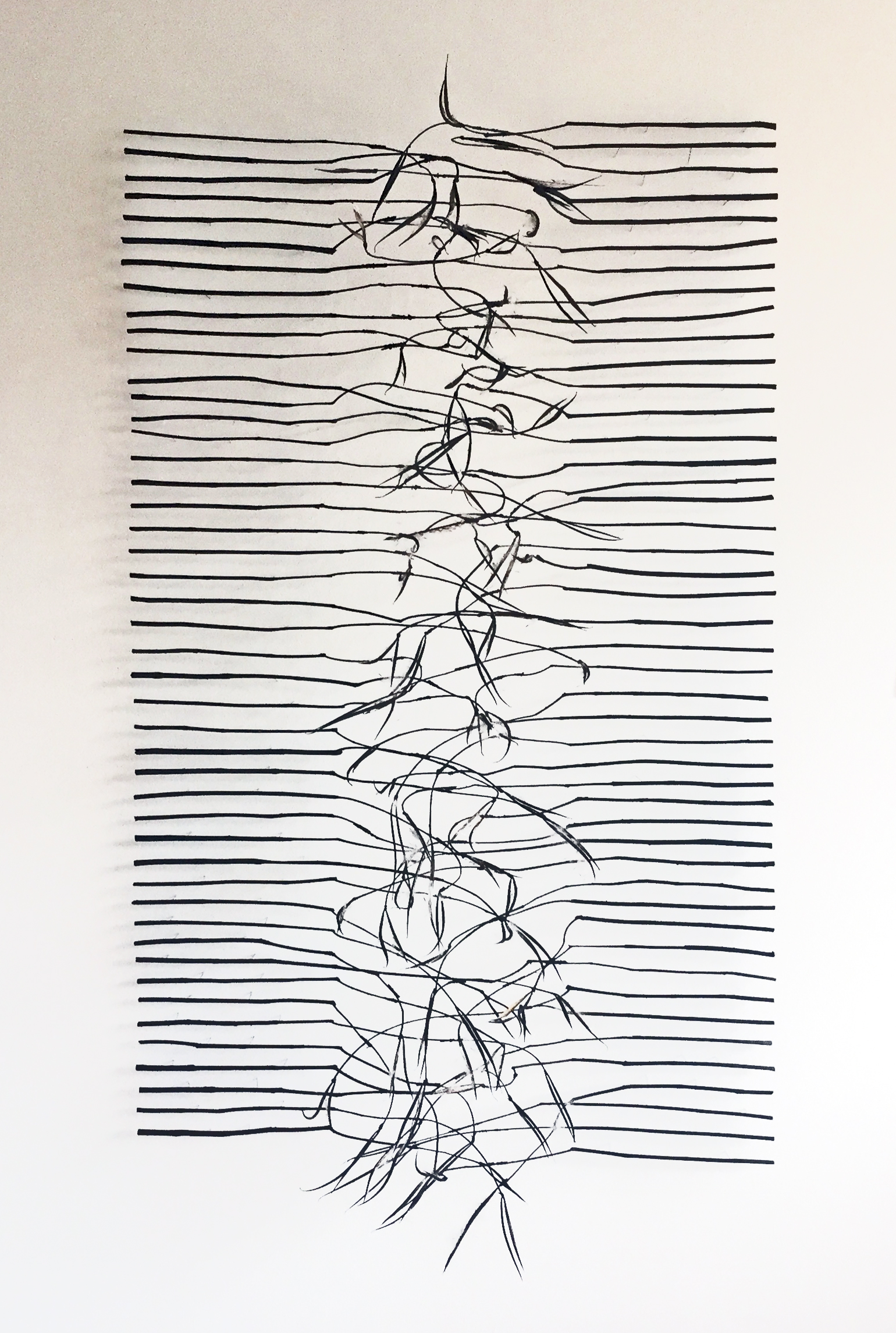

Podcast IV, another large installation drawing, measures six feet in height, and rather than composed solely of branches, incorporates intact the delicate seedpods of the dogbane plant. The seedpods, intended by nature to be wafted to the four corners of the earth, add a decided note of ephemerality to this singular structure. The way a podcast links listener and speaker, albeit fleetingly, is evoked by the flanking vertical forms to either side. Their charged and electric bond, suggested by the overlapping branches and seedpods in tandem with the whiplashing shadows cast on the wall the length of the central section, is delicate and intimate. This ecstatic, sensual interlacing projects from the wall fully 19 inches, the farthest of any of the works in the show. Such animated liaisons between two entities, albeit reciprocal and intense, may however be short and fleeting. So goes the way of all flesh.

Larry Cressman, Gathering Lines, Raspberry cane, powdered graphite, matte medium, pins, 13 x 41 x 2 inches, 2018

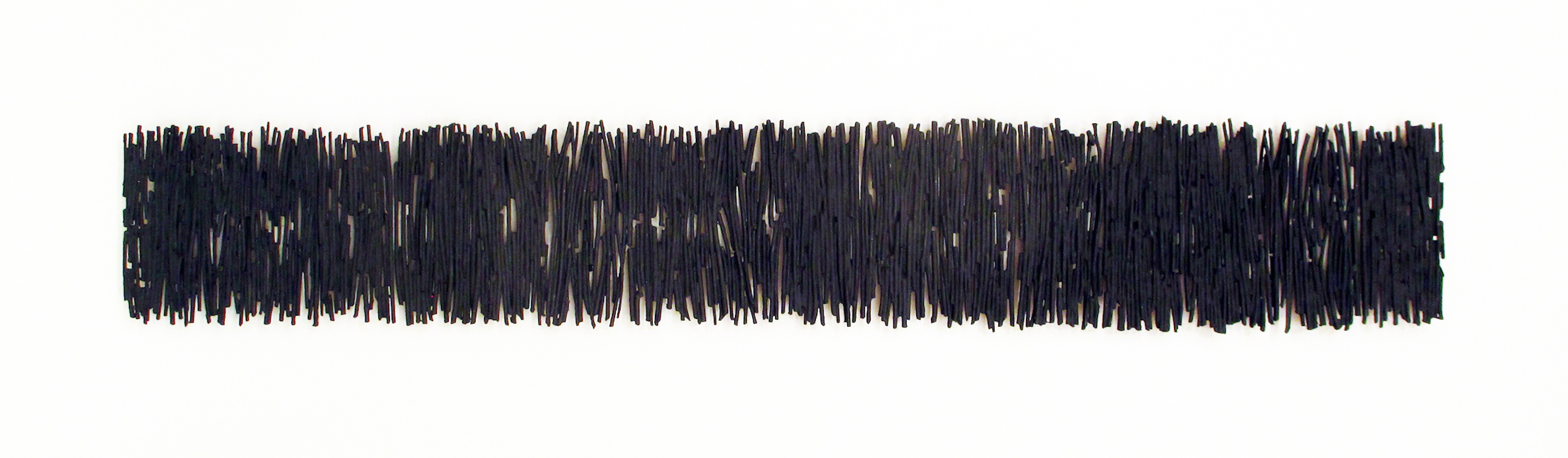

Another striking work, distinctly different in kind from others in the show, is Gathered Lines, an ultra- simple constructed drawing (Cressman’s term for framed vs. installation examples of his art). Here, a densely packed, horizontal sprawl of tightly packed, five inch raspberry canes, thirty-three inches in width, floods one’s peripheral vision. Its concise, dark form seems to belie its “soft” title: gathered lines (as in a family gathering/a gathering of friends). Little breathing space or respite is allotted an observer, as the tug toward the tiny, self-protective cluster envelops one’s whole being, effectively obliterating everything on the margins.

This potent, powerful work, like others in the exhibition, embodies the resonance and spectrum of readings that the artist’s “fieldwork” sets into play, while simultaneously offering aesthetic forms and pleasures. Perhaps Cressman’s summary statement, in which he describes “imagery reflective of the structure, randomness, and fragile nature of the constantly changing Michigan landscape” might be amended to embrace the “changing world” in lieu of the “Michigan landscape.”

“Larry Cressman: Fieldwork” is on view at K.Oss Contemporary Art, 1410 Gratiot Avenue, Detroit, through Dec. 29, 2018. Cressman, who received his BFA and MFA degrees from the University of Michigan, is a Professor Emeritus of the university. An Ann Arbor resident, he has lived and worked in Michigan throughout his career, while exhibiting his works across the United States and Europe.