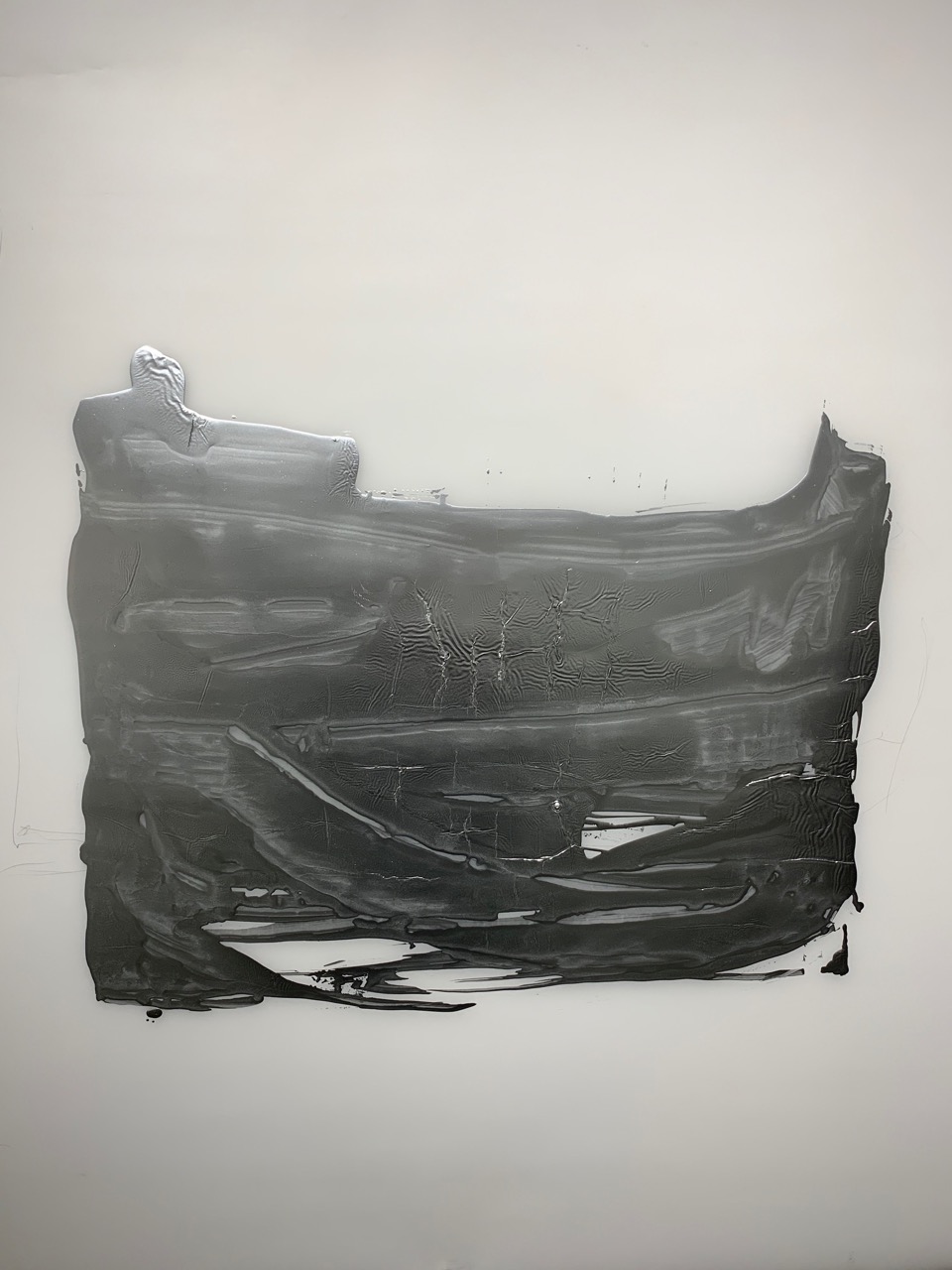

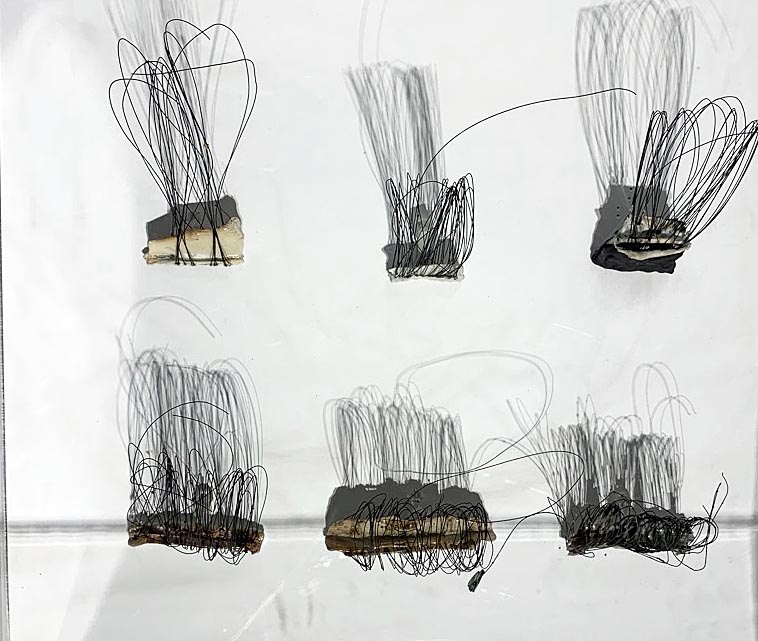

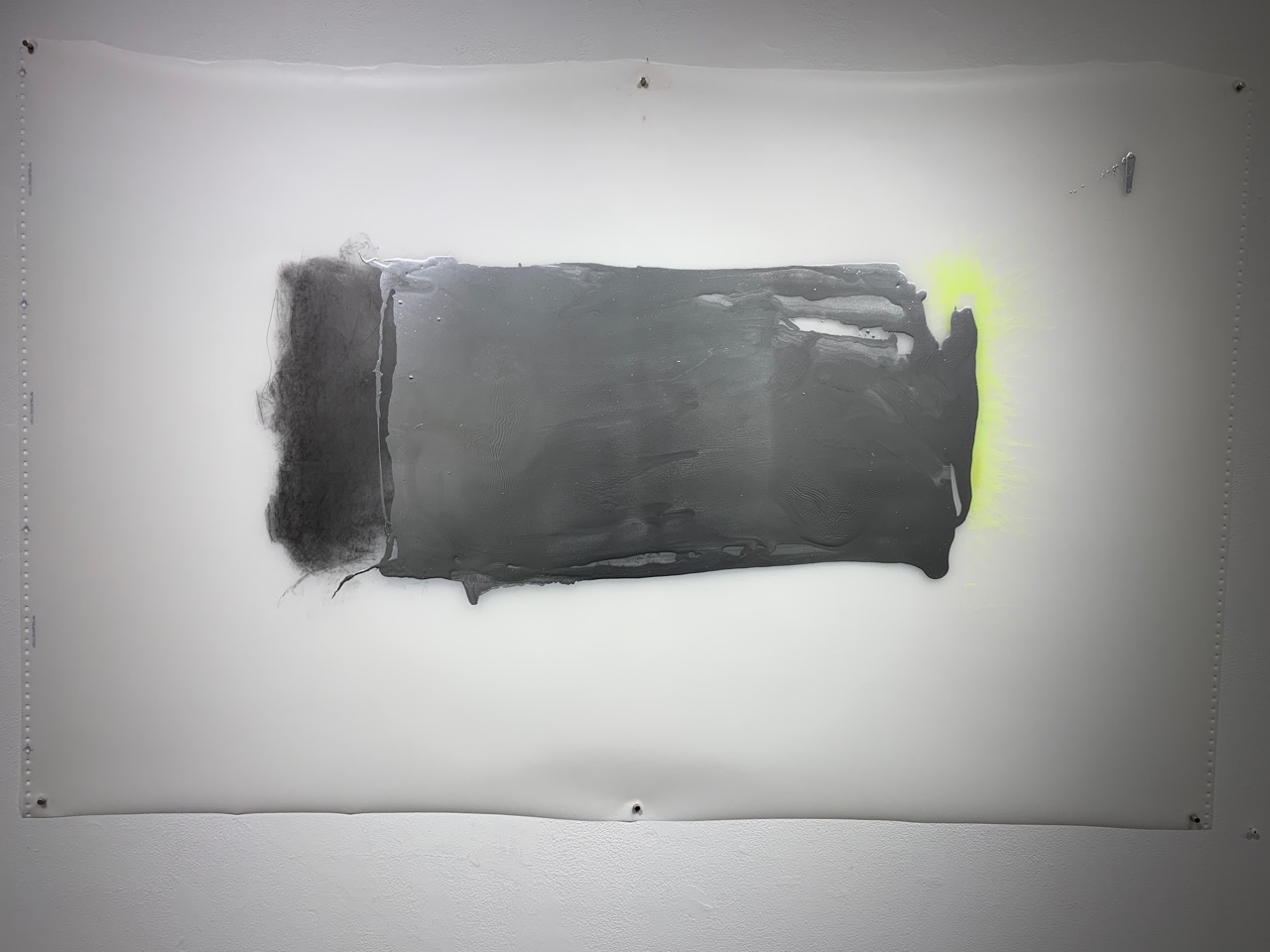

Installation view: Shiva Ahmad opening Photos courtesy of Elaine J. Jacobs Gallery

Shiva Ahmadi @ Elaine L. Jacob Gallery – Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan

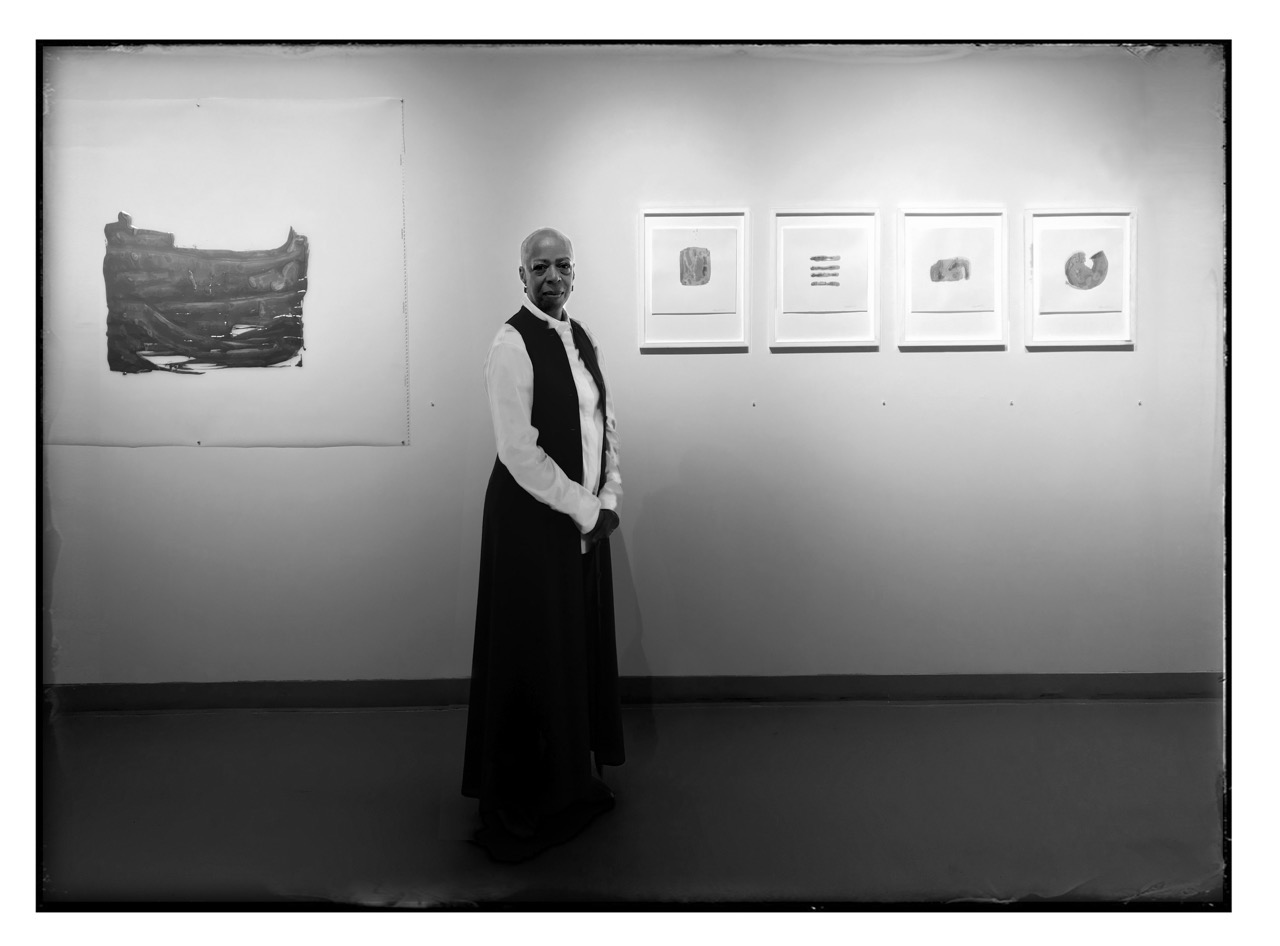

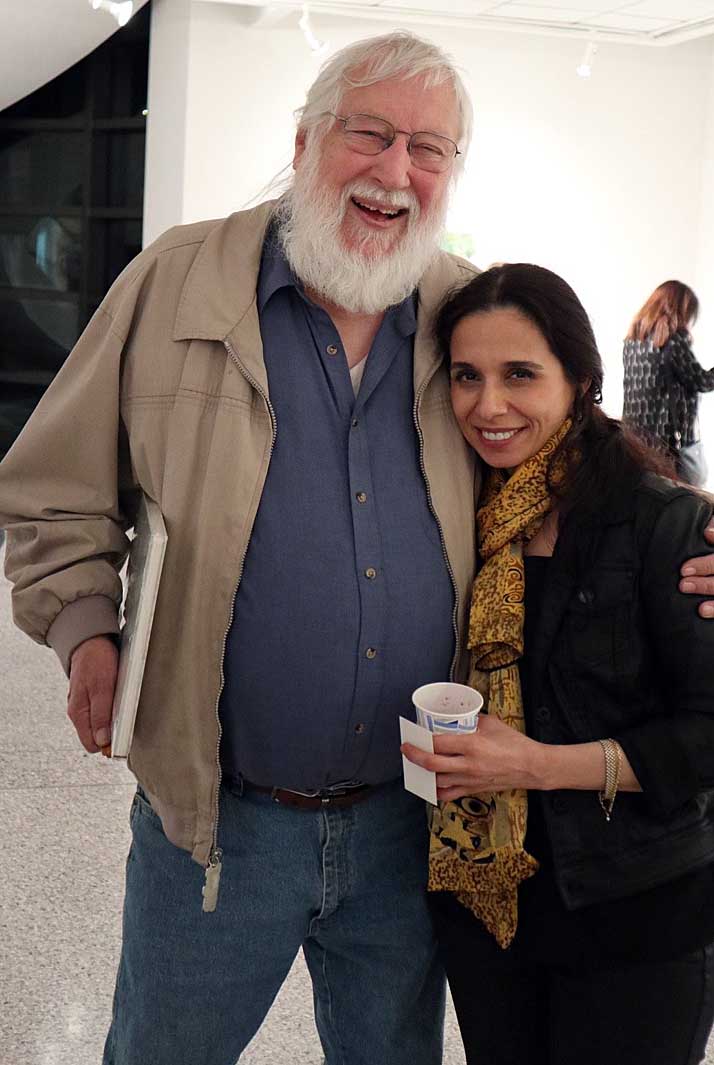

There was a palpable groundswell of pride and affection for Iranian artist Shiva Ahmadi from the audience when Grace Serra, curator of Wayne State University Art Collection, introduced her at her recent talk during the opening of her exhibition, “Labyrinths,” at the Elaine L. Jacob Gallery. Indeed, during her talk she reciprocated the feeling, referencing the faculty of Wayne State University’s art department and Cranbrook Academy of Arts, where she received an MFA in drawing (2003) and MFA in painting (2005) respectively. She honored faculty members who trained and nurtured her there. She remembered the late Professor Stanley Rosenthal’s energetic support who aided her in getting from Tehran, Iran to Detroit (enduring the United States own 9/11 nightmare) and into the WSU Degree program. The legends of Wayne’s art department faculty showed up to celebrate Ahmadi. John Hegerty was there with hugs. Jeffrey Abt leaned over and whispered “Shiva was a marvelous student.” Marilyn Zimmerman sang praises from the audience. Dora Apel exclaimed, “Her work is wonderful.” As an artist, she appeared strong and resolute and as a human being filled with gratitude for what Wayne’s art department had done for her. It was a proud moment for Wayne State University.

At the Opening: Professor John Hegerty and Shiva Ahmadi

Shiva Ahmadi was born in Tehran, Iran in 1975, just before the Islamic Revolution that overthrew the Shah and the Iraq-Iran war that wreaked bloody mayhem on both countries for years and still continues. An estimated million people were slaughtered. As a child, Ahmadi witnessed and lived through that bloodshed. It’s the prime mover of her current body of work.

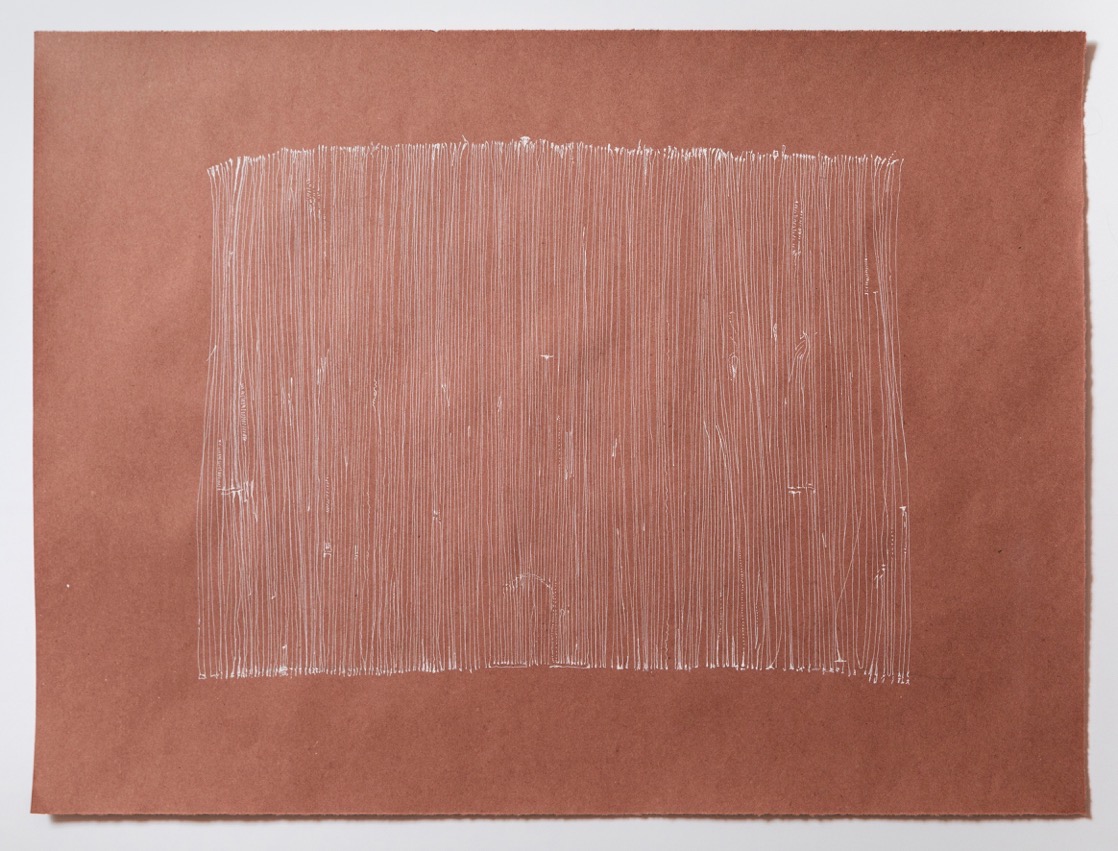

Shiva Ahmadi, “The Wall,”2016, Watercolor and ink on paper, 40” X 60”

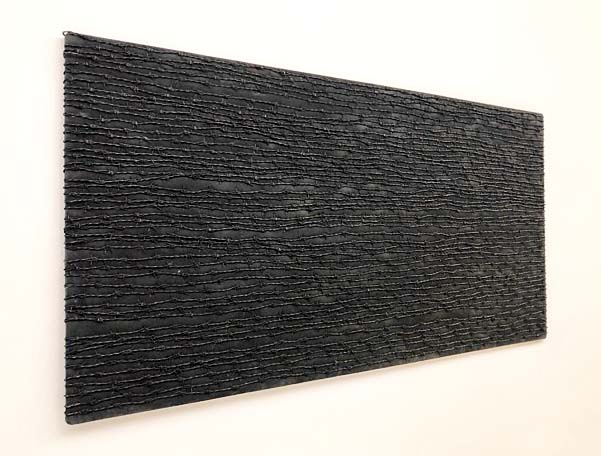

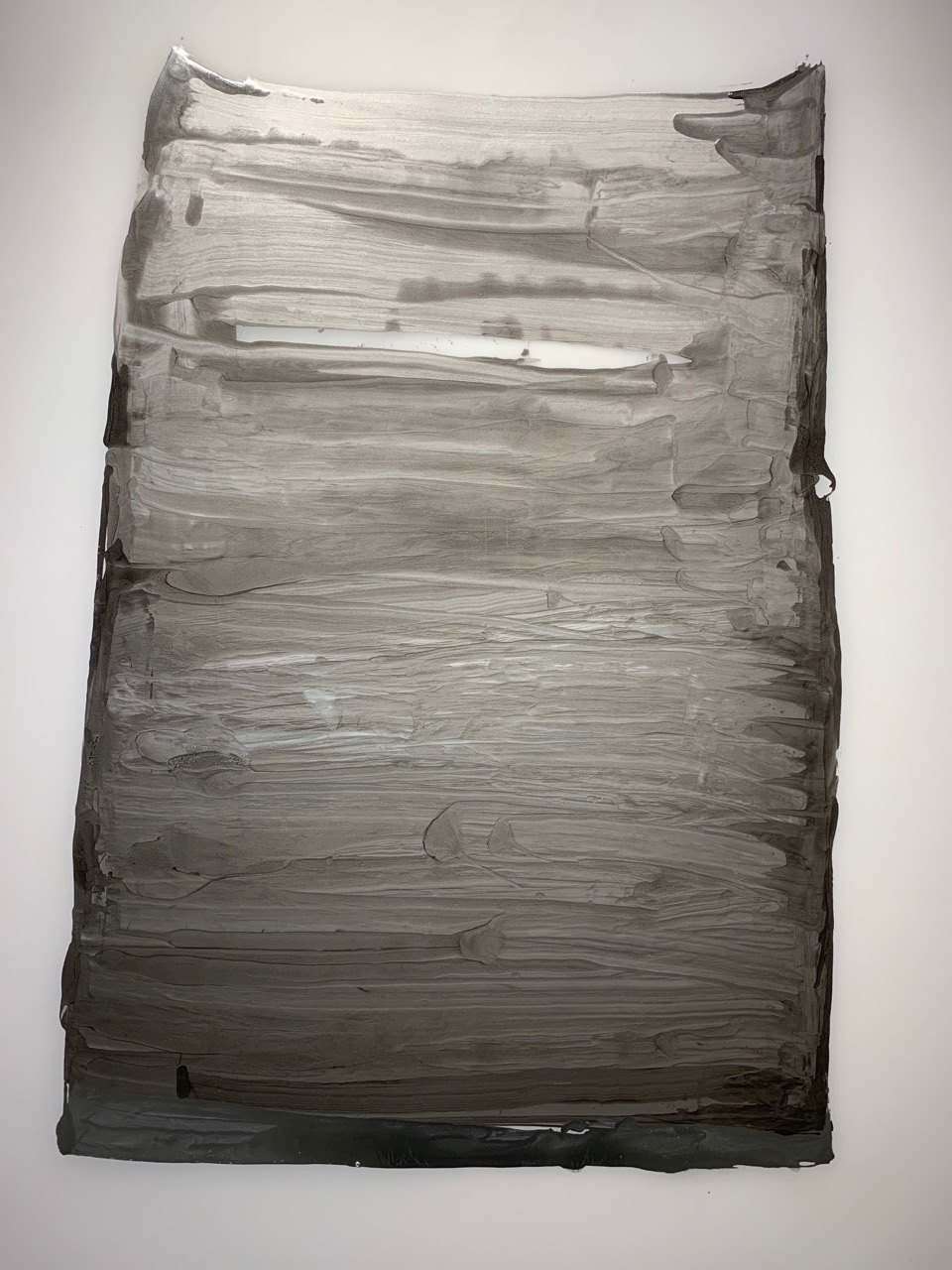

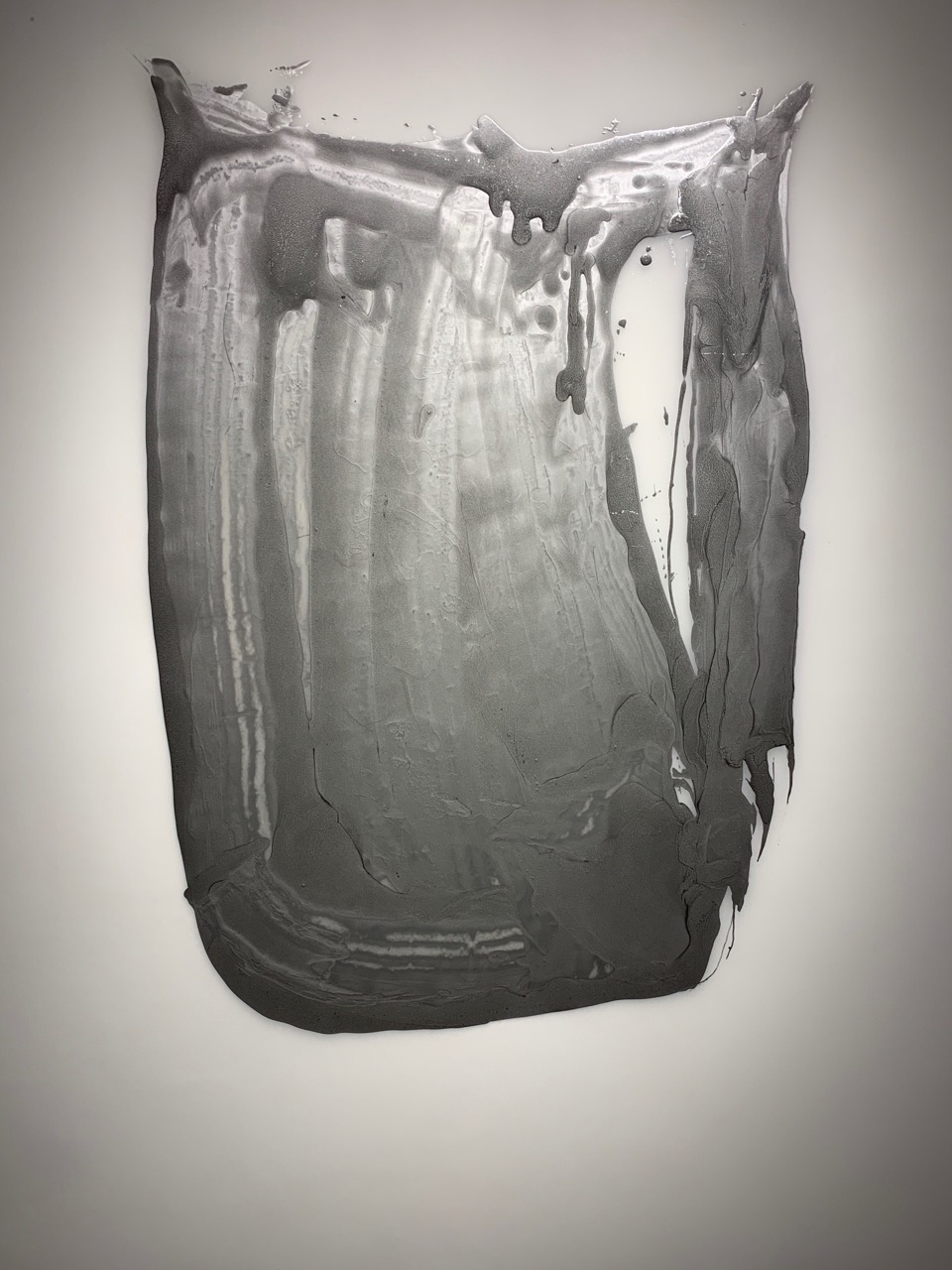

In a mix of water color, ink, acrylic, and video, Ahmadi’s “Labyrinths” engages a meditation on the dynamics of capricious power, mindless loyalty, blood and oil economics and war. Inspired by the tradition of miniature paintings of Persia, stunningly drawn, large scale watercolor and ink drawings establish an index of characters—animal and human figures— set in a haunting landscape. Ahmadi’s tableaux usually situated in walled or gardenlike landscapes, insulated interiors, controlled by an often-empty throne. The large watercolors, “The Knot,” “Mesh,” and “The Wall,” 2016, establish and illustrate the cosmology of Ahmadi’s world. And she can draw. Always beguilingly lyrical, her faceless figures (parody of Islamic aniconism?) float aimlessly, in her magical but existential emptiness, waiting.

In these remarkably executed watercolors, a captivating choreography of Ahmadi’s characters pay mindless fealty to elaborately decorated thrones (Persian history), signifying 2500 years of history. Ahmadi’s primate-like, docile minions carry out the job of salaaming the throne and among other things, seem to be processing uranium for operating nuclear reactors, and like graceful automatons, juggle beautiful bubbles into bombs. In “Minaret,” (2017) four interconnected minarets, towers used to call the faithful to prayer, are represented as nuclear towers for nuclear energy and bombs. Like the Persian miniatures, Ahmadi’s palette of colors is composed of rich earth tones punctuated by a background of transparent watercolor wash. They are elegant yet they are drawn with purpose as if from memory.

Shiva Ahmadi, “Minaret,” 2017, Watercolor on paper, 20.5” x 29.5 “

If Islamic miniatures are the main inspiration for Ahmadi’s iconography, the modern cartoon seems to have also played its part. In conversation Shiva alluded to her youthful preoccupation of watching cartoons. While most Persian miniatures are densely packed with a precisely drawn geometry of figures and architectural spaces, Ahmadi’s open spaced compositions read, cartoon-like, as sites of movement and action, suggesting metaphoric narratives. Some of the loose gestural watercolor figures resemble cartoon characters but the brush work comes straight out of abstract expressionism. The tableaux in “Green Painting” and “Burning Car,” employing aggressive brushwork of globs of paint, read as horrific attacks on the home and individual lives and the bloody gore, as if painted with human viscera itself, the nightmare of revolution. One cannot ultimately help but read them as a kind of personal exorcism of the nightmare Ahmadi has witnessed. Some of the works, like “Burning Car,” read as Biblical representations of hell itself with demonic human figures in combat rending others into bloody gore.

Shiva Ahmadi, “Burning Car,” 2019 Acrylic and Watercolor on Aquaboard, 36” x 46 “

Ahmadi has also translated pressure cookers, used in many terrorist attacks as bombs (including the 2013 Boston Marathon that killed three and maimed hundreds), into sculptures, filled with nails and adorned with intaglio hand-etching with Arabic script and Islamic decoration, becoming satires on sanctity Islamic culture. The brutal irony of the text that is etched on them is that it is what Muslims pray before they die.

Shiva Ahmadi, “Pressure Cooker #4,” 2016, Etching on Aluminum Pressure cooker 10 x 19.5 x 12 inches

Two videos animate Ahmadi’s drawings into mesmerizing narratives that critique the nature of political and religious power. “Lotus,” commissioned by the Asian Society Museum, proposes what would happen if the Buddha, a surrogate for God, loses his enlightenment, signified by the flight of the word for God or Allah in Farsi, snatched by a dove, leaving the throne Godless. Leaving the servile devotees without a spiritual center, the landscape is thrown into total chaos, populated by Ahmadi’s now meaningless, randomly dispersed figures and objects. The implications of Lotus are global.

Shiva Ahmadi, “Lotus,” 2013, Watercolor, ink and acrylic on Aquaboard, 60” X 120”

“Ascend,” is an animation that tells the recent, internationally read, news story of the life of a Syrian child refuge whose body was washed up on the shore of Turkish coast, after his family attempted to flee war torn Syria, hoping for a safer life in Europe and eventually Vancouver, Canada. The video is painfully lyrical, composed of Ahmadi’s animal figures frolicking together with bubbling toys which ultimately leads to the young boy’s drowned body washed ashore.

Aside from the current relevance of her subject matter, the attraction of Ahmadi’s painting is quite simply the combination of the elegance and deftness of her drawing and the masterful handling of paint and watercolor on the paper. Her work gains traction by the apt appropriation of Islamic iconography, turning it on its head and reversing its message. Ahmadi is a testimony to the significant role artists can play, but don’t often enough, in giving shape to our political dialogue.

Elaine L. Jacob Gallery Wayne State University

·

LABYRINTHS: Shiva Ahmadi

Dates: January 16 through March 20, 2020

Gallery Hours: Wednesdays through Fridays, 1-5PM