Dr. Anita Bates’s exhibition, A Long Time Coming, now on view at N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Arts revives a fresh experience to Abstract Expressionism.

Installation, Anita Bates, N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art 2023. All images courtesy of DAR.

Detroit artist Anita Bates opened her exhibition, A Long Time Coming, at N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art on September 9, 2023, with recent abstraction expressionistic paintings rich in color, scale, line, texture, and composition. The paintings are like forest flowers, reminding this writer of music performed so exquisitely in the 1960s by the jazz musician Charles Lloyd. Gestural strokes, mark-making, and the impression of spontaneity characterize the work. Her creative process over the past thirty years follows in the footsteps of Willem de Kooning (and others), but she focuses on the color field, devoid of any reference to the landscape or figure.

Abstract Expressionism emerged in the early 1940s, primarily in New York, where a small group of loosely affiliated artists created a diverse body of work that introduced new directions in painting—and shifted the art world’s focus forever. In distinction to the emotional energy and gestural surface marks of abstract expressionists such as Pollock and de Kooning, the Color Field painters initially appeared to be cool and austere, effacing the individual mark in favor of large, flat areas of color, which these artists considered to be the essential nature of visual abstraction, along with the actual shape of the canvas. However, Color Field painting has proven to be sensual and deeply expressive, albeit different from gestural abstract expressionism.

Bates says in her statement, “The colors found in the majority of the work in this exhibition are lighter than previous bodies of work; they are colors associated with my childhood but seen through the eyes of maturity. I primarily work in the triadic combinations of green, orange, and purple or a palette of red together and always gravitate towards these hues while consistently pushing my knowledge of these harmonies via desaturation and contrast. For me, this element of art and design demonstrates my growth as an artist; The ability to make color transition with tints, tones and shades.”

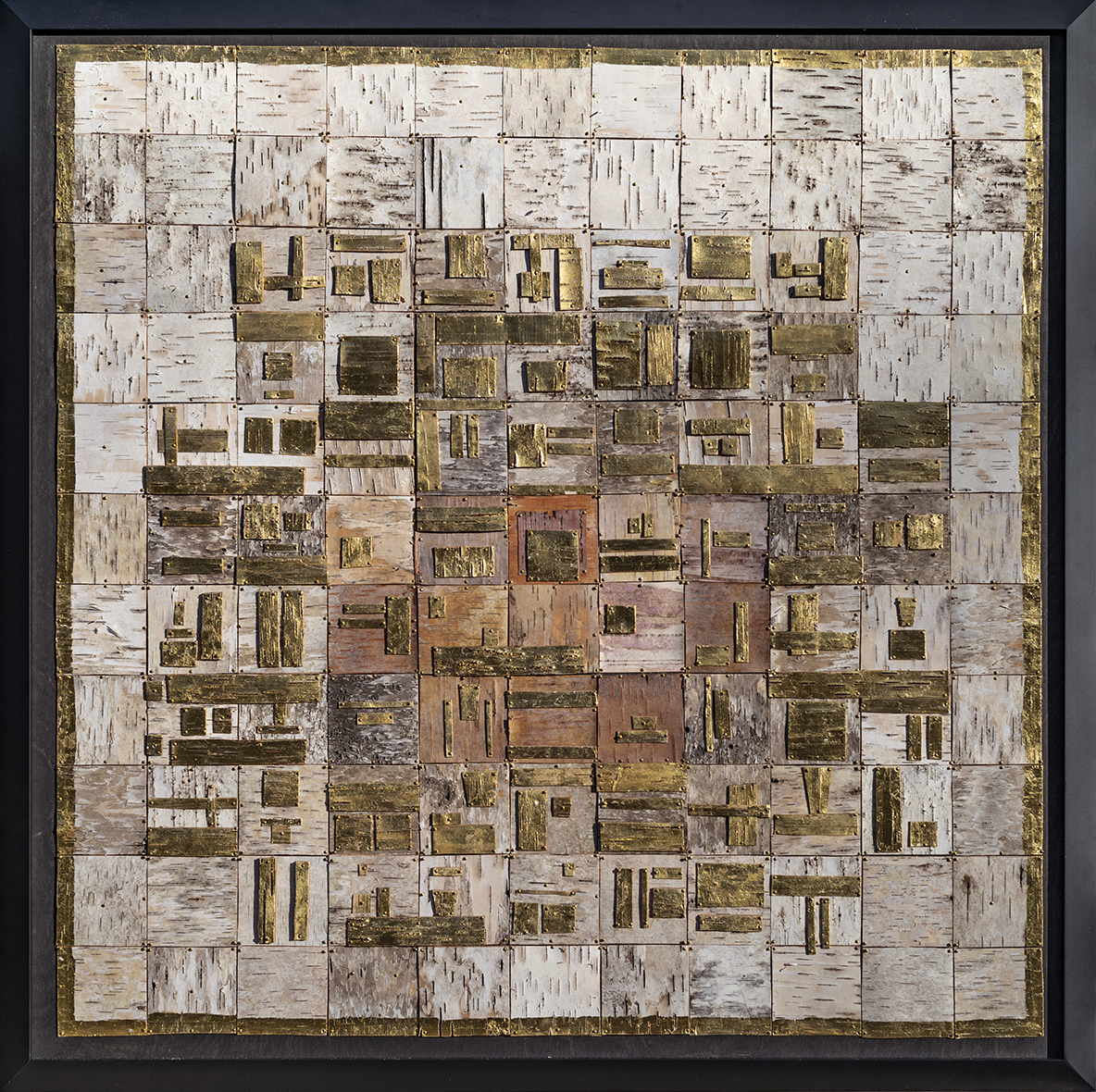

Anita Bates, The Power of Subtlety, Mixed Media on Canvas, 2023

The two diptych canvases, 30 X 46” each, and entitled The Power of Subtlety, are connected with a black horizontal line in the top quarter, providing the geometric compositional structure for the overall painting. The background throughout is a sloshing around of pastel colors from her triad of green, orange, and purple, where transparent blends of white and tan merge. Possibly influenced by artist Lee Krasner, Bates plants herself in color field composition with oddly shaped abstract elements. The dominant feeling is esoteric, with a personalized set of small, mysterious objects that keep the viewer at bay. The artist seems to be saying that the painting does not need to convey a meaning other than the way it makes the viewer feel.

For Abstract Expressionists, the authenticity or value of a work lies in its directness and immediacy of expression. A painting is meant to be a reveal of the artist’s identity. The gesture, the artist’s “signature,” is evidence of the actual process of the work’s creation.

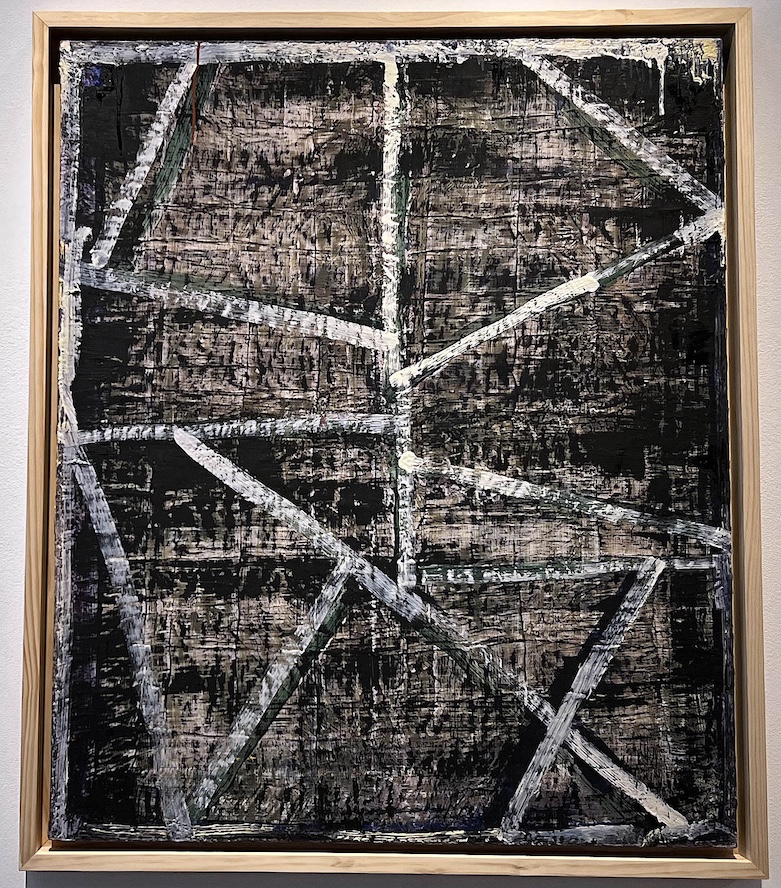

Anita Bates.The Zoo, 60X96″, Mixed Media on Canvas, 2023

The Zoo, another 30 X46” diptych, is more lively, with a much larger color palette that includes details of black drawing and a more integrated overlapping of shapes. Is it a Zoo? If so, it is one not so much of animals but of contrasting shapes from the artist’s subconscious reflecting her sensibility. There is a lot more compositional traffic in The Zoo that speaks to the language of her attraction to the overlapping and action-packed gesture of Abstract Expressionism.

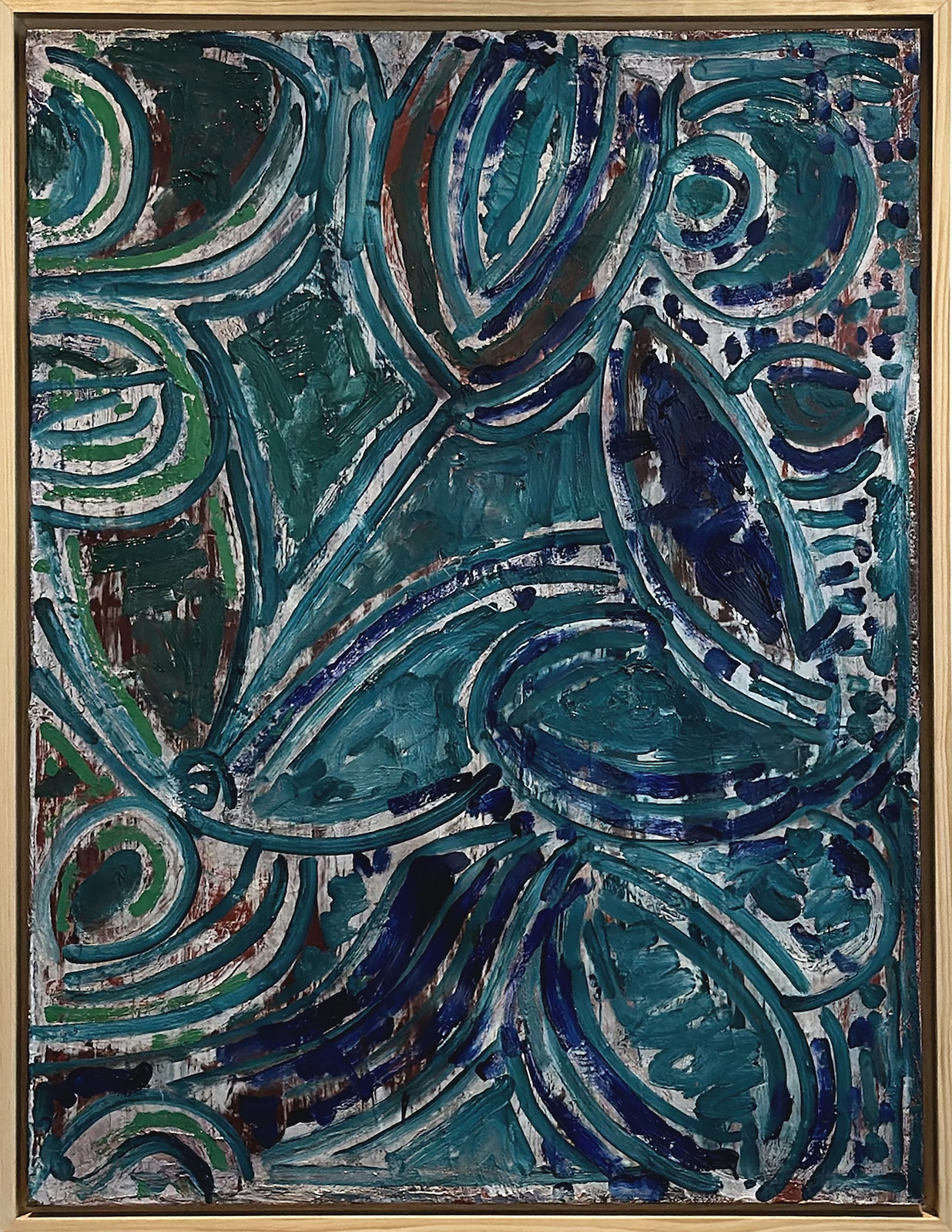

Anita Bates, Poivres Rouge, 60×72″, Mixed Media on canvas,

Poivres Rouge is a mixed-media painting on canvas that divides the space into quarters and places its weight in the center of this organic composition. The title refers to a French restaurant or, in the dictionary, defined as Pepper, perhaps based on the artist’s travels in France.

Early art critics, like Harold Rosenberg, had long been outspoken in their view of a painting as an arena which to come to terms with the act of creation. To Clement Greenberg, the physicality of the paintings’ clotted, dripping, and oil-caked surfaces was the key to understanding these works as documents of the artists’ existential struggle. Bates seems to occupy a middle ground since her paintings are non-referential yet emotive.

Anita Bates, Candy, 60×96″, Mixed Media, 2023

Staying with a familiar palette of color in Candy, Bates presents layers of oil paint working from dark to light with a multitude of overlapping shapes, lines, and drips as she balances the congestion of abstraction. Brush strokes move horizontally and vertically, and a balanced of black drawing helps hold the picture together. There is a distinct push and pull of paint, solvents, and water, mixing to create diverse textures.

Like the Charles Lloyd album from 1966, Forest Flower, the uplifting abstractions in A Long Time Coming draw the viewer back… and then back again for more observation and discovery.

Dr. Anita Bates earned her Ph.D. in Education and an M.F.A. in painting from Wayne State University. She was a 2019 Kresge Arts Fellow, resides as a native of Highland Park, Michigan, and has widely exhibited throughout Metro Detroit and beyond. https://www.anitabatestheartist.com/

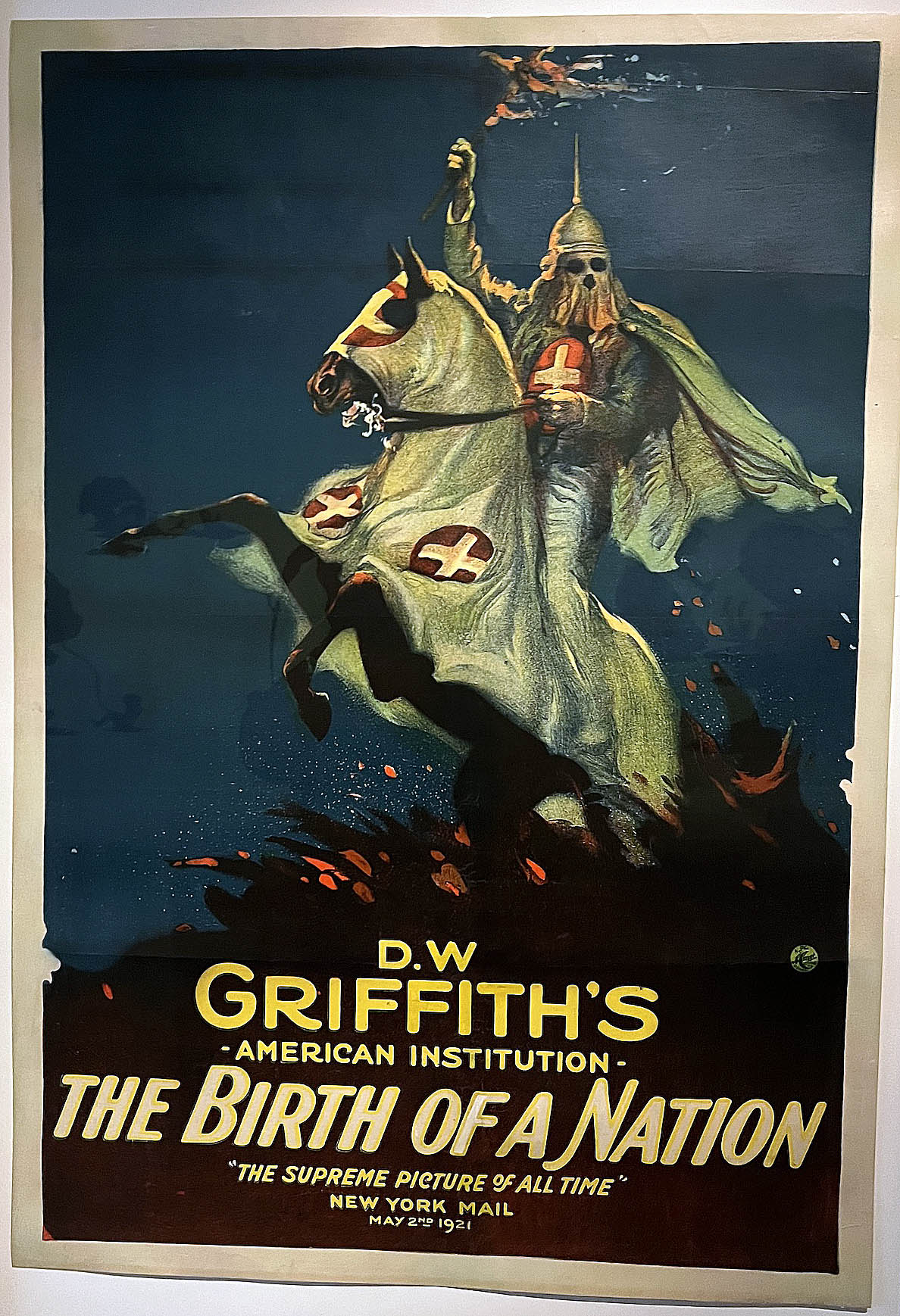

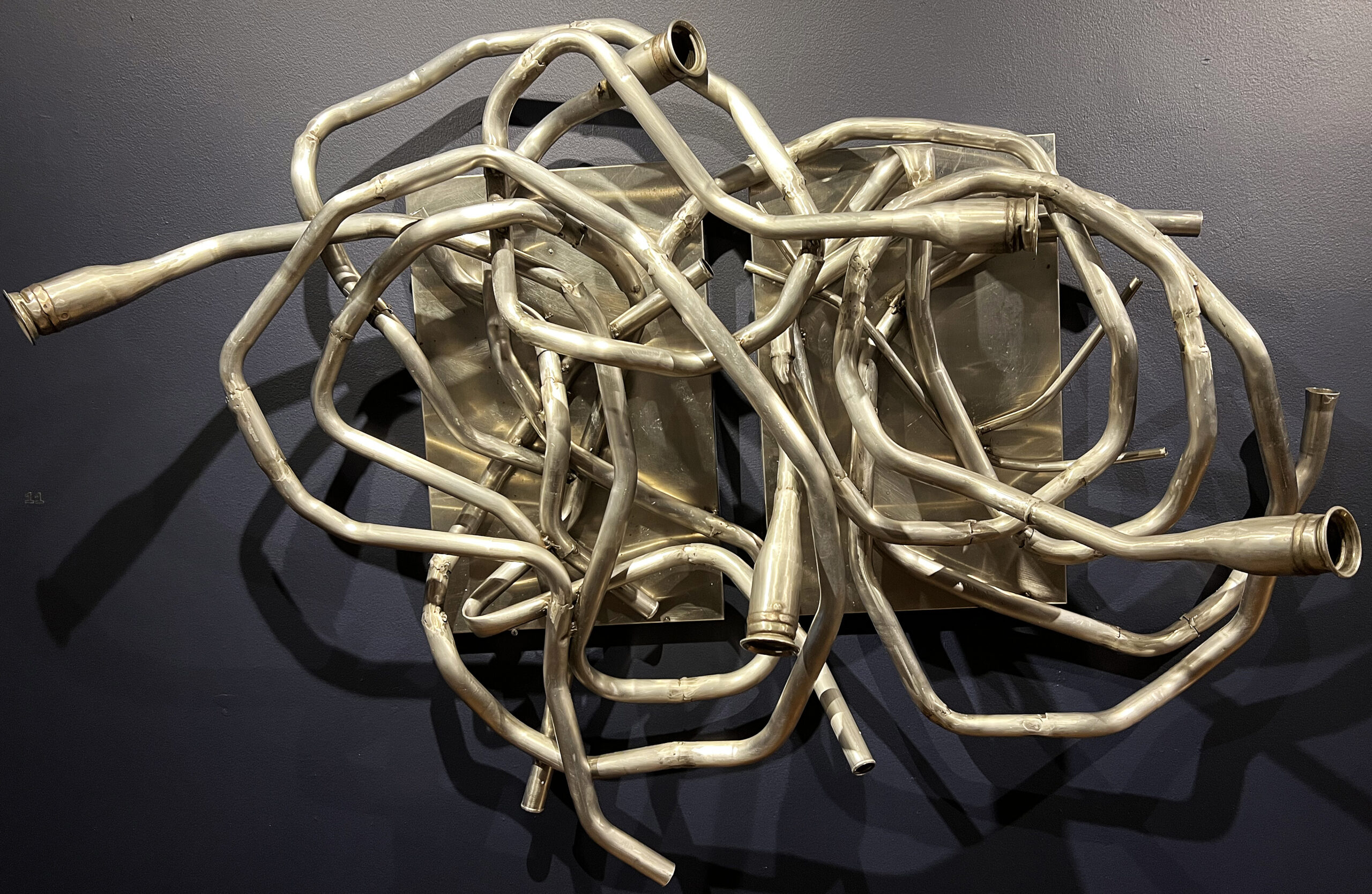

Lucy Slivinski @ N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art

The Improvisation of Matter Into Magic

Installation Lucy Slivinski sculpture N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art

Critically acclaimed artist Lucy Slivinski hails from Chicago, Illinois, bringing her wide collection of sculptures and installations. For over 40 years, as one of the few female artists working in metal, Slivinski has created abstract sculptures for interior and exterior residential and commercial spaces. Most of her contemporary sculpture features found objects, scrap metal, and other locally sourced, recycled products that would otherwise end up in a landfill or smelting factory, continuing to harm the environment. As an abstract artist, Slivinski’s unique style has been commissioned for many large outdoor public sculptures, live performances, and gallery installations.

Lucy Slivinski earned an M.F.A. from Cranbrook Academy of Art and a B.F.A. from Northern Illinois University.

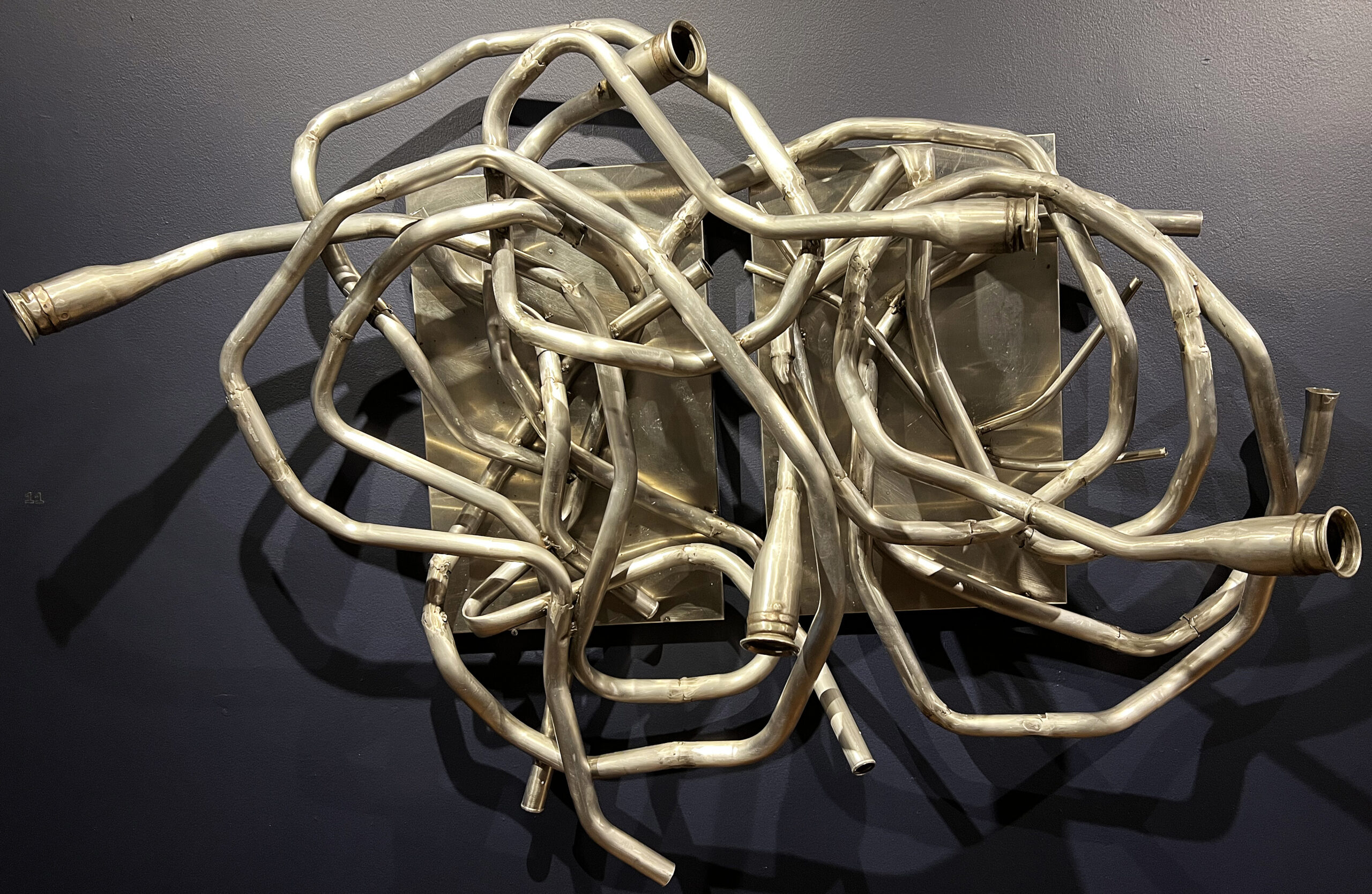

Herbert Gentry @ N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art

Installation Herbert Gentry N’Namdi Center for the Arts 2023

Herbert Gentry’s paintings juxtapose faces and masks, shifting orientations of figures and heads—human and animal—into profiles to the left, to the right, above, and below. The direction of the head, as face or profile, leading right or left, or facing front, is played against the relative scale of each head, its position on the canvas, and its relationship to the others. The faces evoke subtle expressions and moods. Rather than using images to depict a concrete story, Gentry releases his experiences upon the canvas. Born in Pittsburgh, PA, Mr. Gentry was raised in Harlem during the highly creative Harlem Renaissance period. He served as a member of the Armed Forces in World War II, and his early commitment to art was confirmed upon his return to Paris in 1946, where he studied painting.

Three Gallery Exhibitions, September 9 – through November 30, 2023