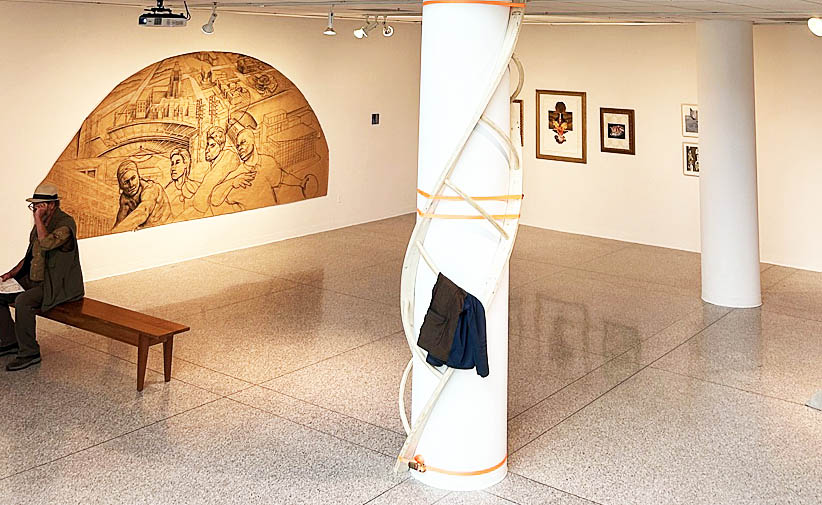

Heloisa Pomfret, Installation image, and image of the artist in a black dress. All images courtesy of DAR

On November 1, 2024, the George N’Namdi Gallery opened a solo exhibition, “The Brain,” by Brazilian-American artist Heloisa Promfret. This collection of 45 artworks builds on her earlier work, including abstract paintings using the palimpsest process, where layers of paint are scratched into the surface, revealing further colors beneath. Despite lacking a specific context in contemporary art history, Pomfret’s work combines mysterious marks, multiple colors, and shapes executed on burlap, paper, and ceramic objects.

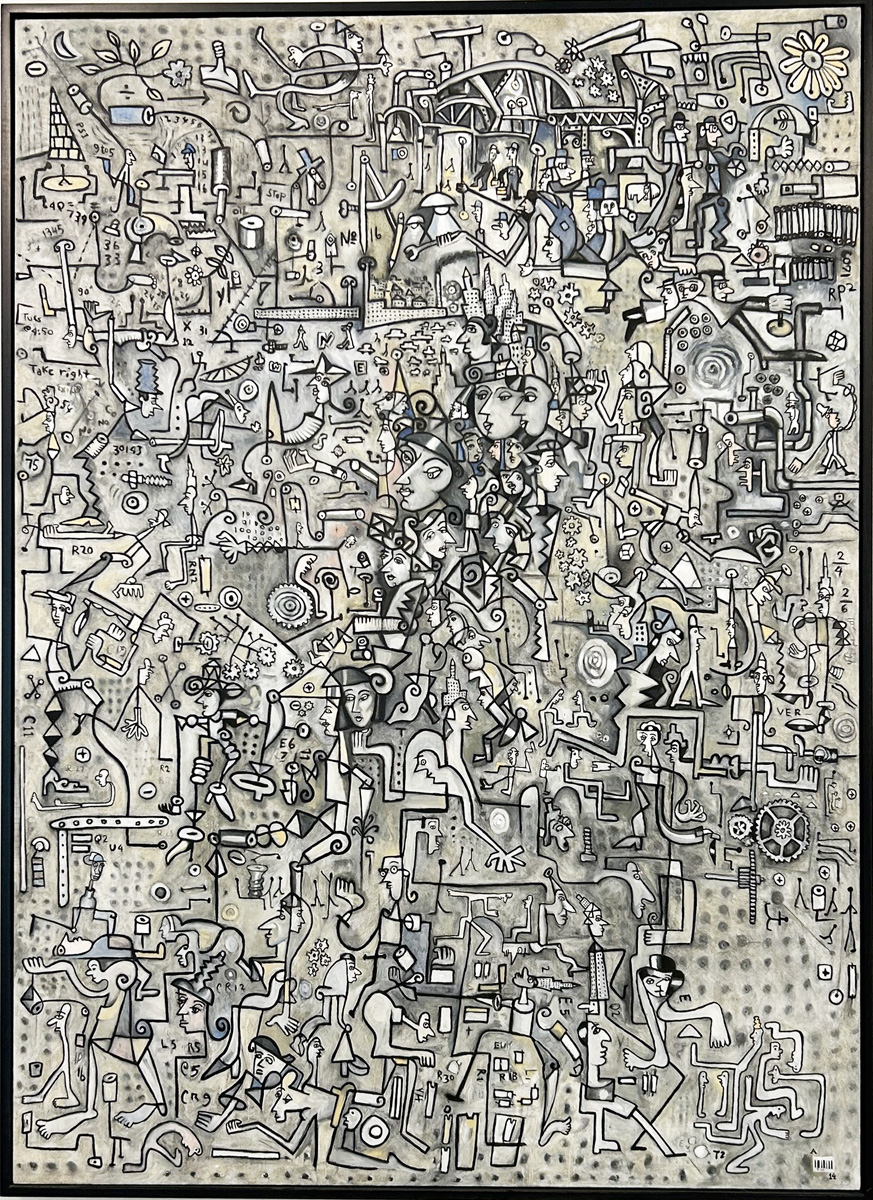

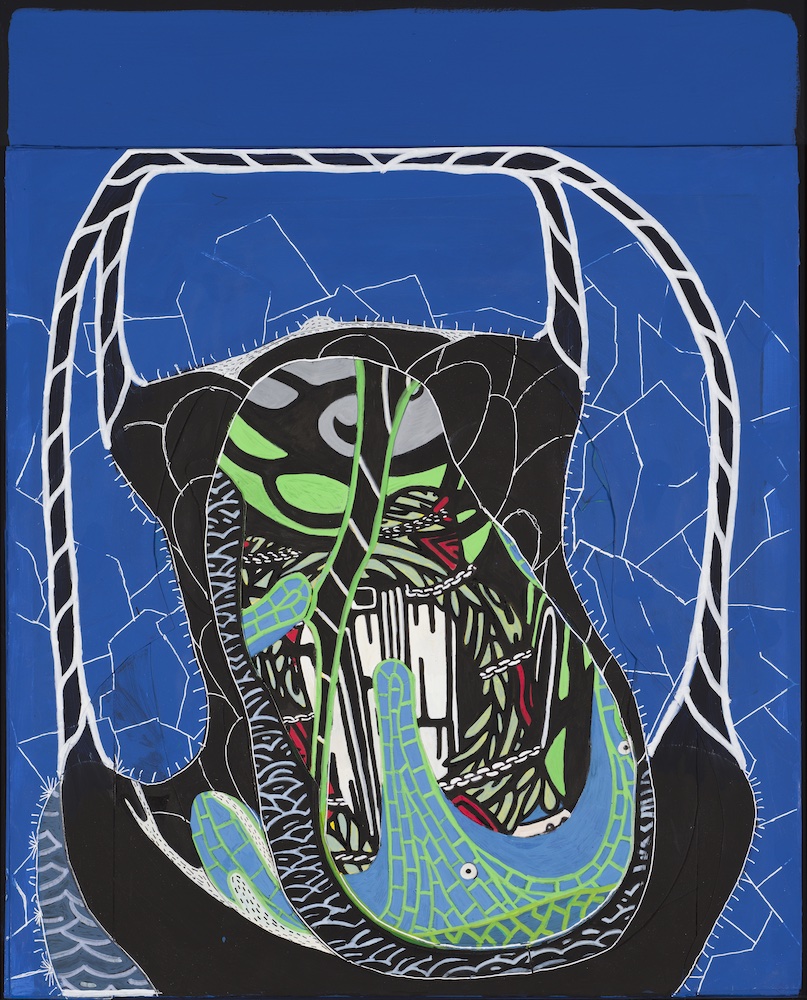

Helosia Pomfret, Untitled #7, Diptych 34 x 36″ 2024

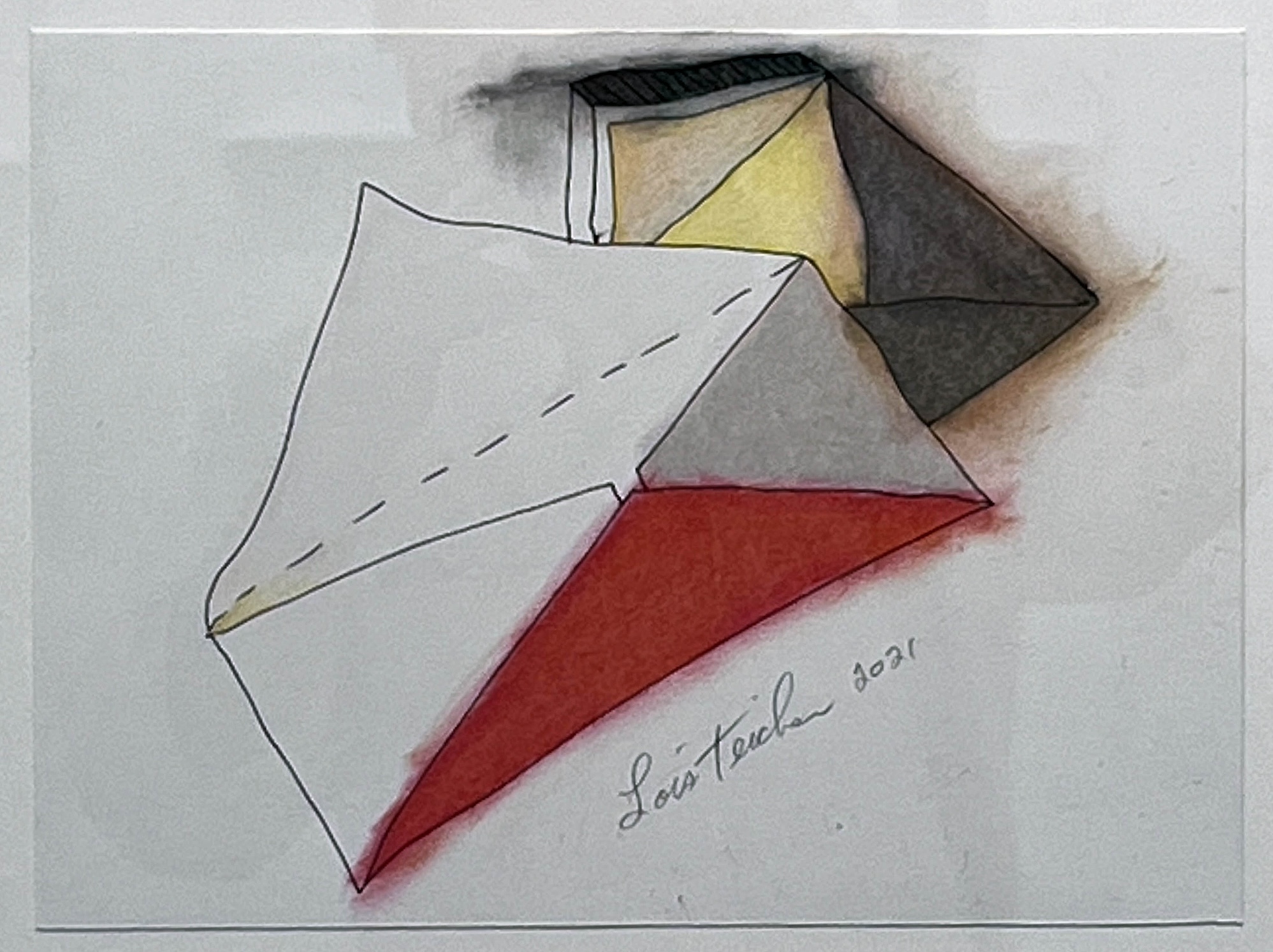

Diptych, Untitled #7, displays a multicolored, organic, abstract composition in which the canvas is cut, re-arranged, and re-stitched. She says, “My work involves the transformation first from the idea of an impulse to scientific representation and measurement, and second, from scientific representation back to abstracted mark-making, color, texture, and re-purposed and re-constructed materials.” These plant-like shapes illustrate a new environment for the viewer to ponder.

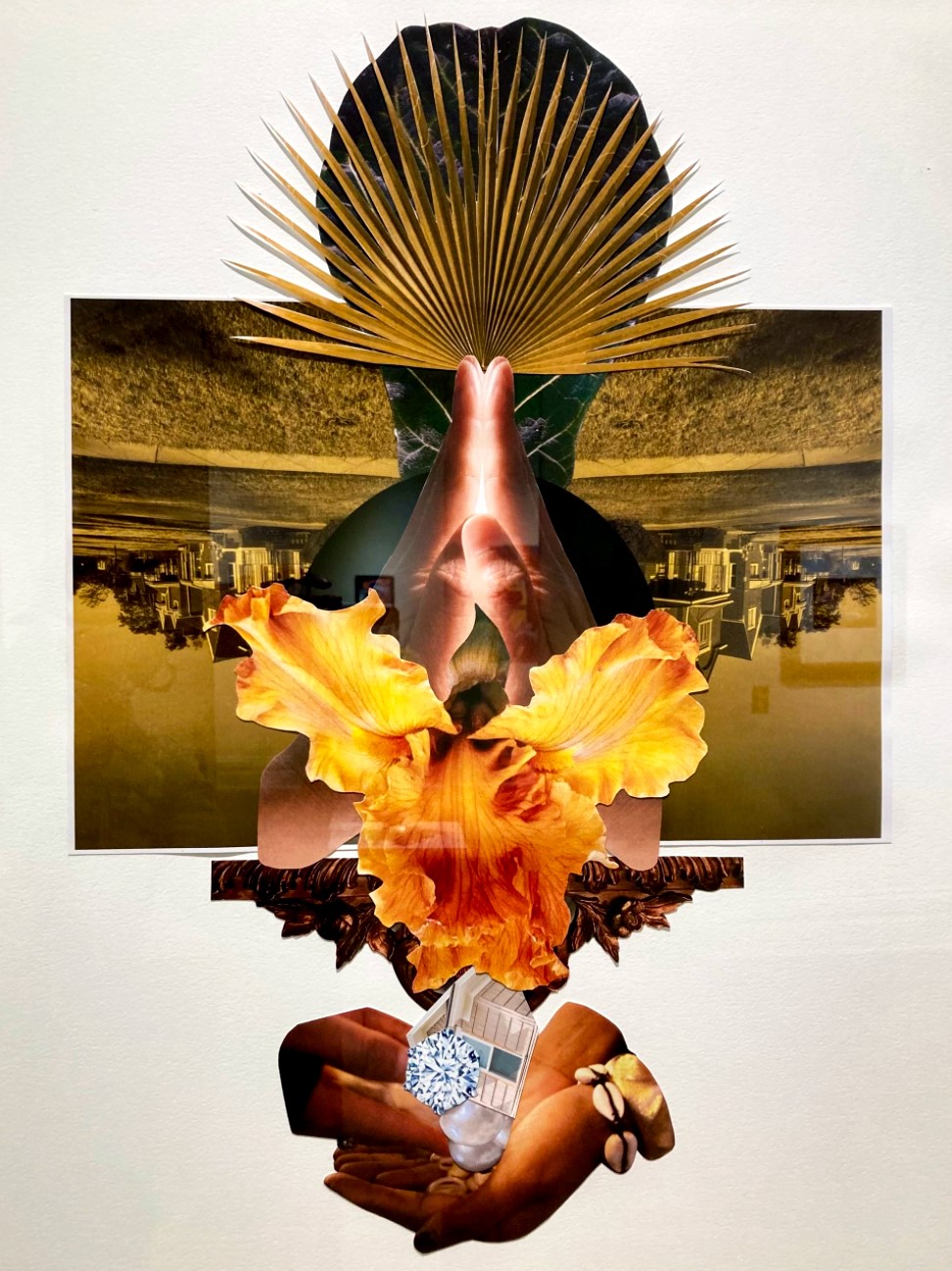

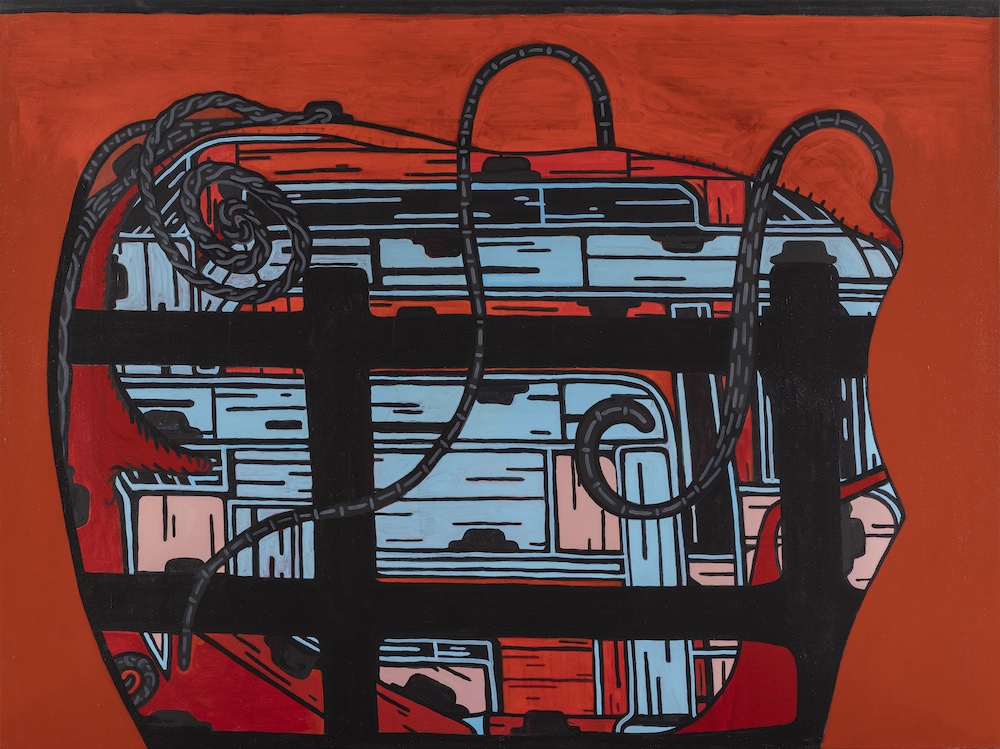

Helosia Pomfret, Glimpse Series, #2, Oil on Stitched Canvas, 38 x 53″. 2024

In the painting Untitled #2, the artist confronts her audience with a wall of movement that contrasts these vertical panels against a sea of shapes and colors moving from right to left in the background. The small, dark shapes feel like microbes swimming over the scratched surfaces. It is a primitive dance, as energy, order, and chaos co-occur during the movement concert. Raised in Brazil and later relocated to Detroit for her study of art, one wonders if something in her South American DNA makes these compositions so unusually new and fresh.

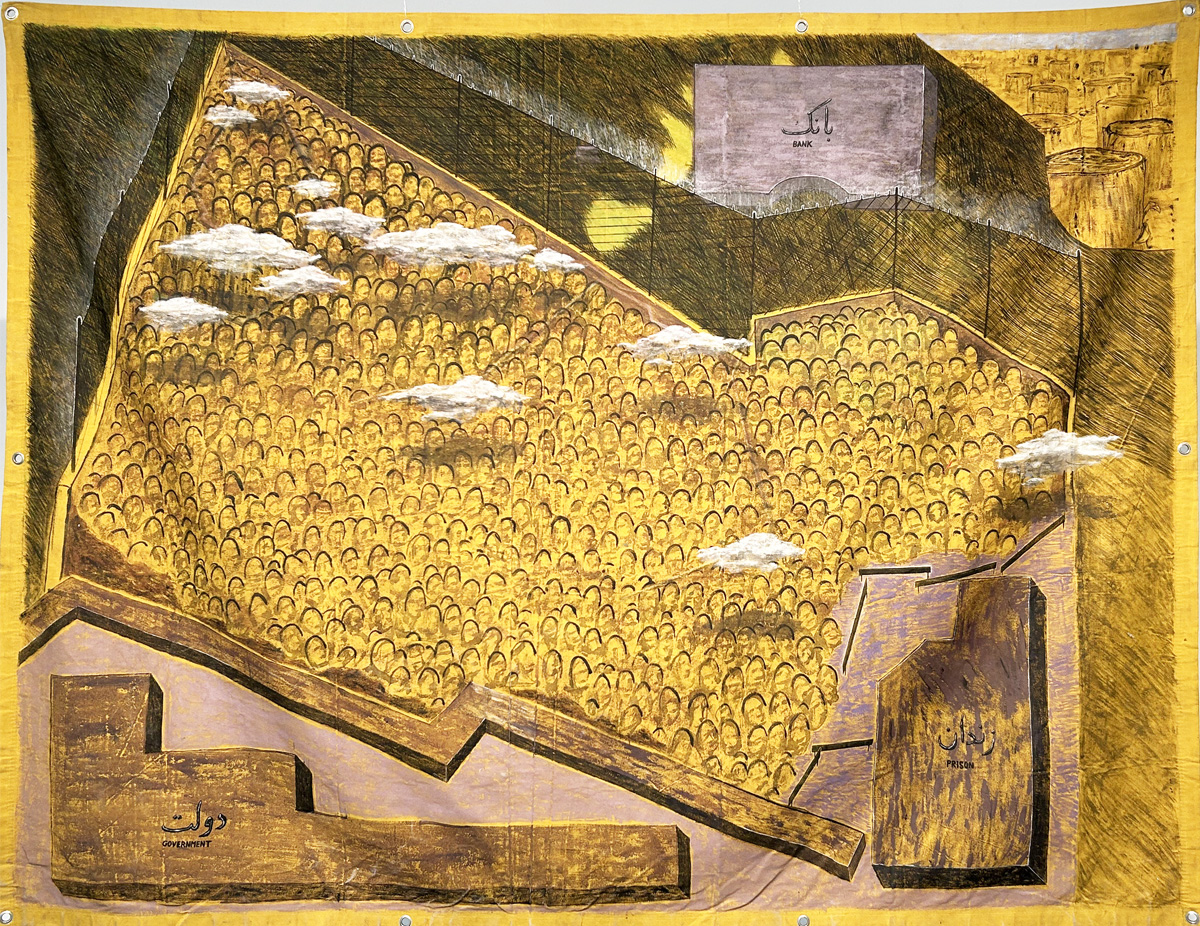

Heloise Pomfret, Untitled # 6, Glimpse Series, 36×34″ 2024

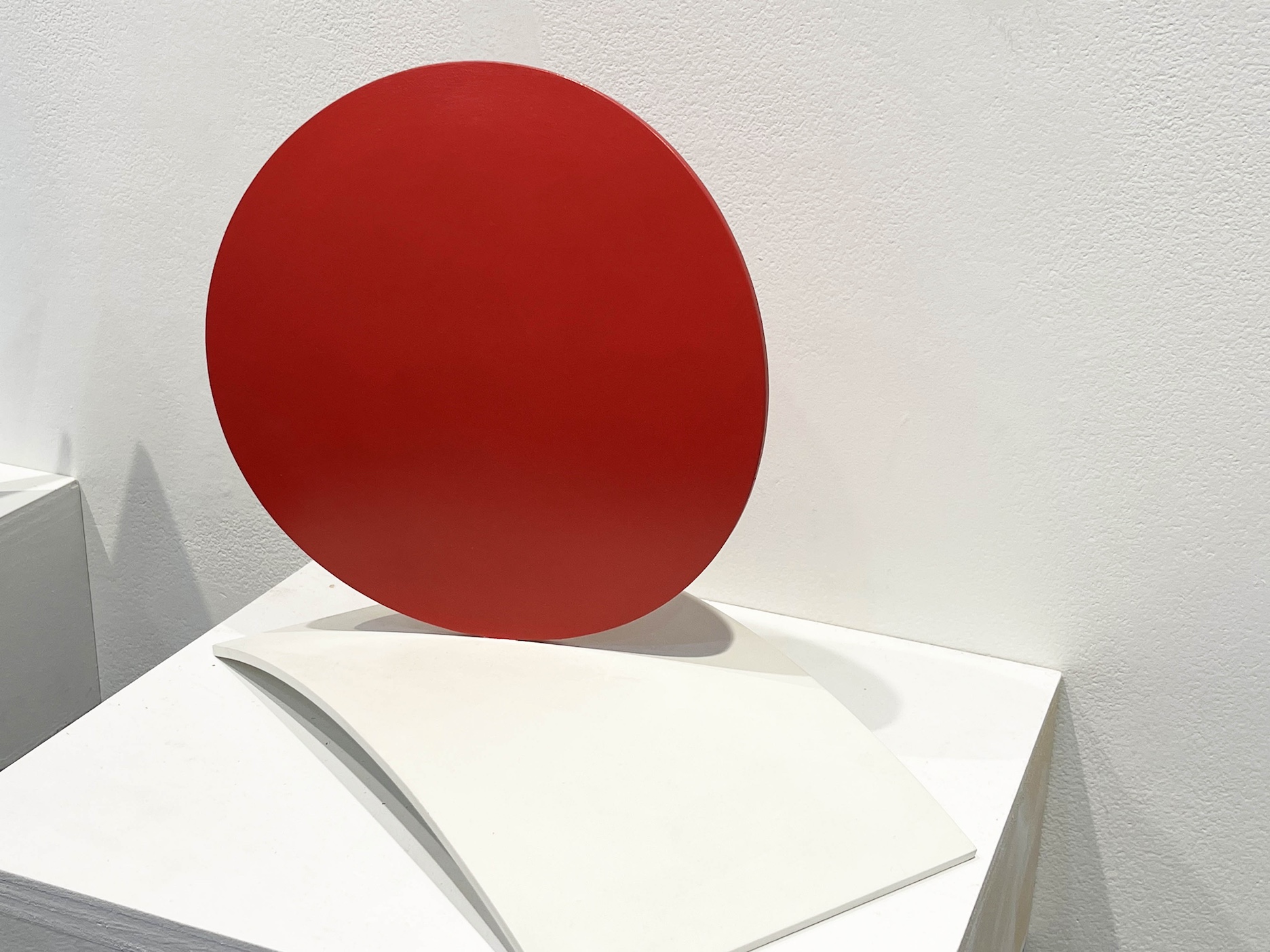

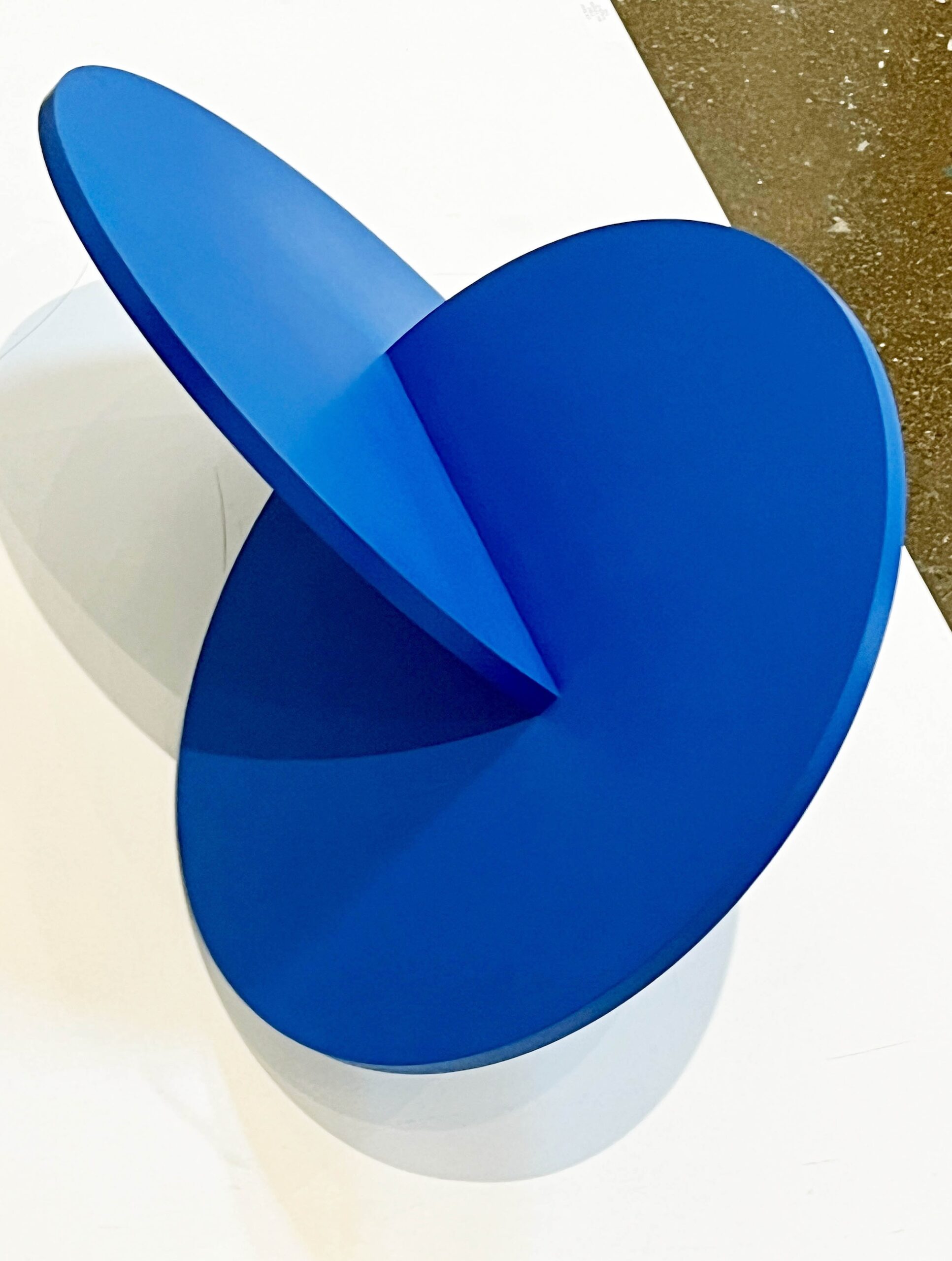

The series of Mandala-like circular paintings located in the gallery provides a contrast to the horizontal compositions and flirts with the idea of scientific explosions on the planet. They are an entirely different kind of sensibility that occupies the artist’s conceptions, especially when making the transition from rectangle to circle.

She says in her statement, “My work involves the transformation first from the idea of an impulse to scientific representation and measurement, and second, from scientific representation back to abstracted mark-making, color, texture and re-purposed using re-constructed materials.” There is a mobile and versatile side of Heloise Pomfret’s work in the exhibition when you consider the paintings, the structures, and the ceramics.

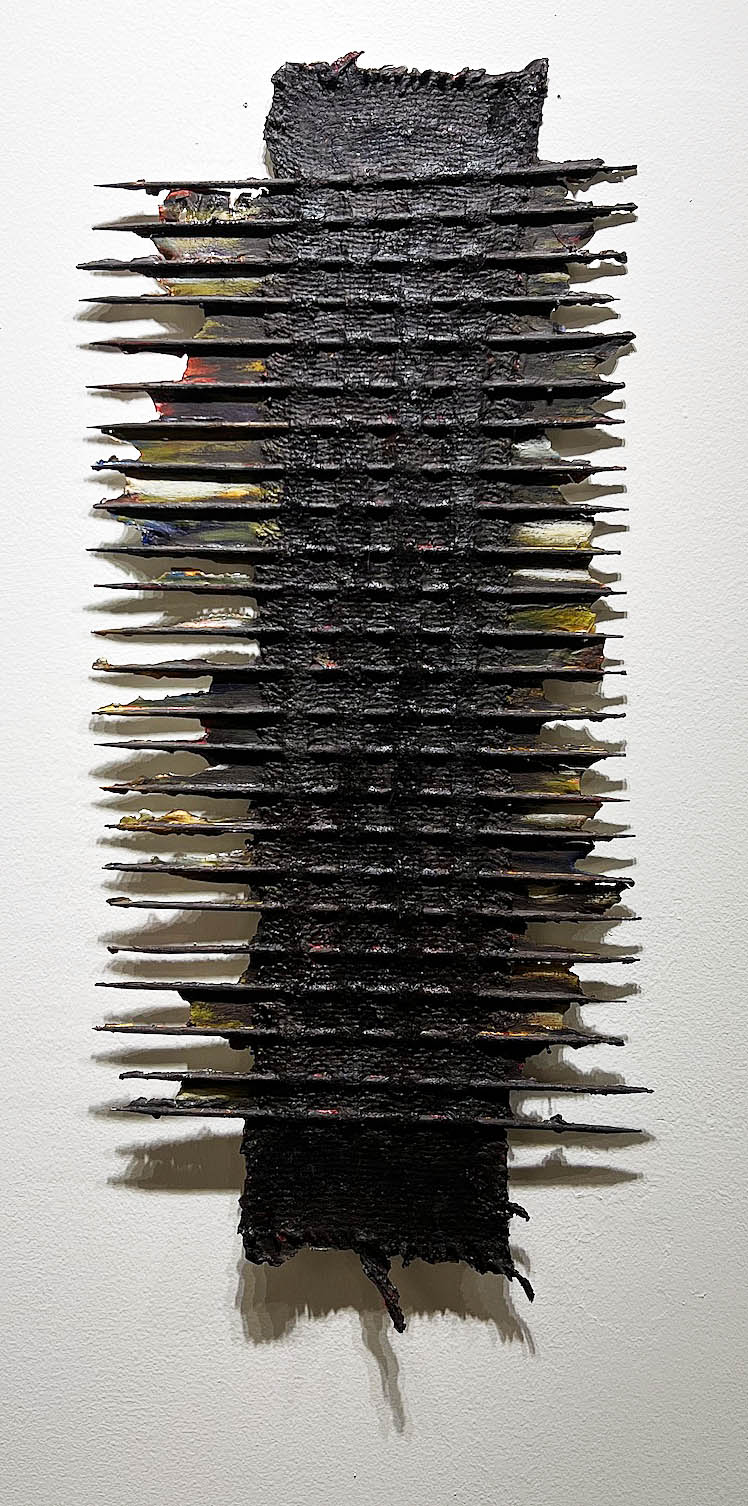

Heloise Pomfret, Construction # 8, Burlap, oil, and Bamboo, 25 x 12″. 2024

In Bamboo, the relief construction uses oil to create a dark vertical grid that feels like something produced by native people of South America. Stitched onto burlap, it suggests some spiritual practice to this viewer. She says, “The philosophy of my work is about the energy, order, and chaos that occurs during psychological or physical stress, which serves as theoretical support to the mark-making and constructs of my work. The surface is often an analogy to the body and memory, in which experience occurs and is transformed.”

Heloise Pomfret, Clarity Series, Stoneware, 6 Pieces, 9×5″, 2023

It is not often that an artist whose primary work is two-dimensional will make drawings, prints, or photographs, but even less frequently will they create a ceramic body of work. Yet, in this exhibition, Heloisa Pomfret presents a series of 15 ceramic objects. Most are wall reliefs; she chooses stoneware with a black glaze to express her ideas. In the Clarity series, she scratches her motifs into the glaze, in keeping with the other bodies of work she has created for this exhibition.

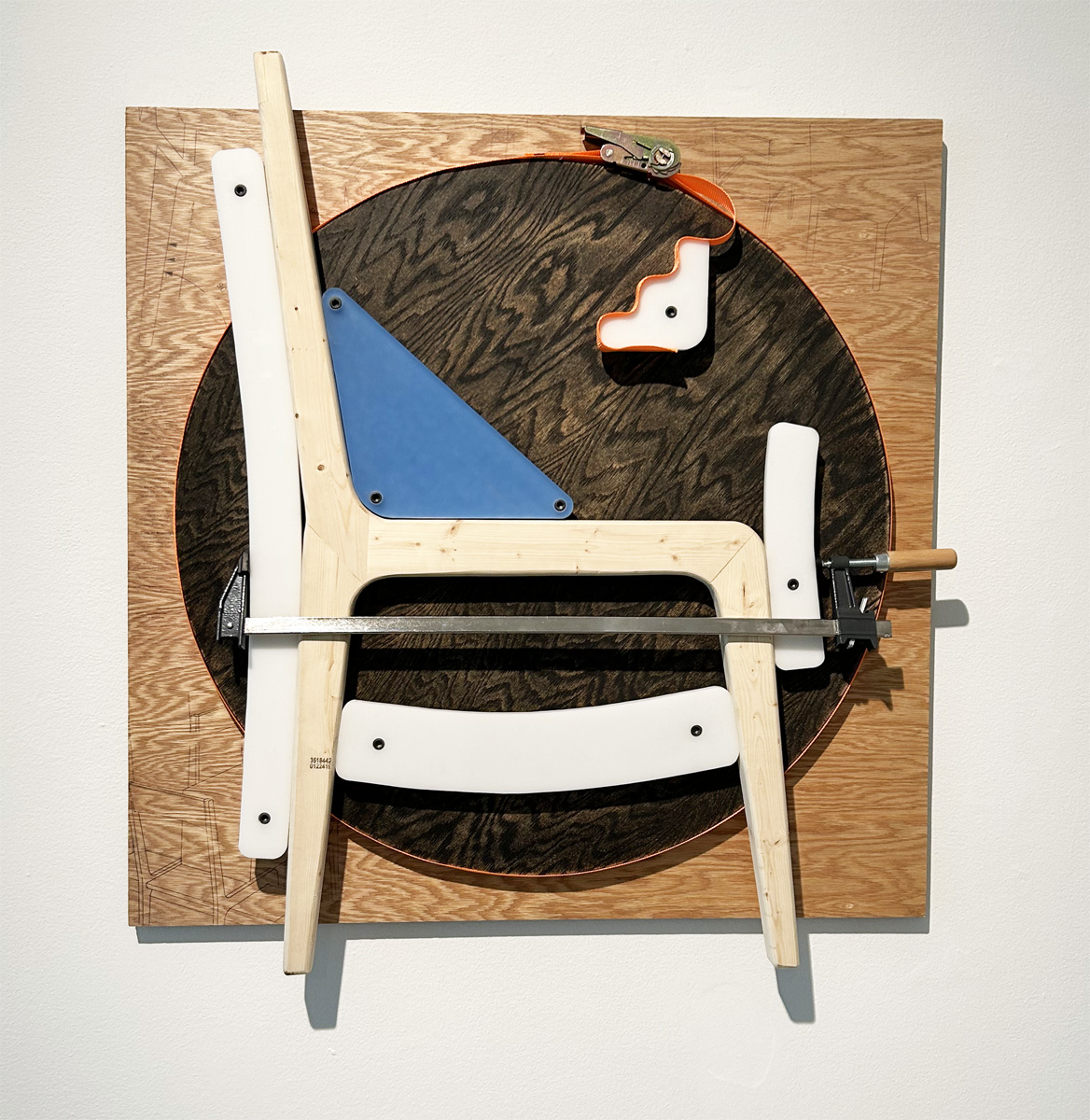

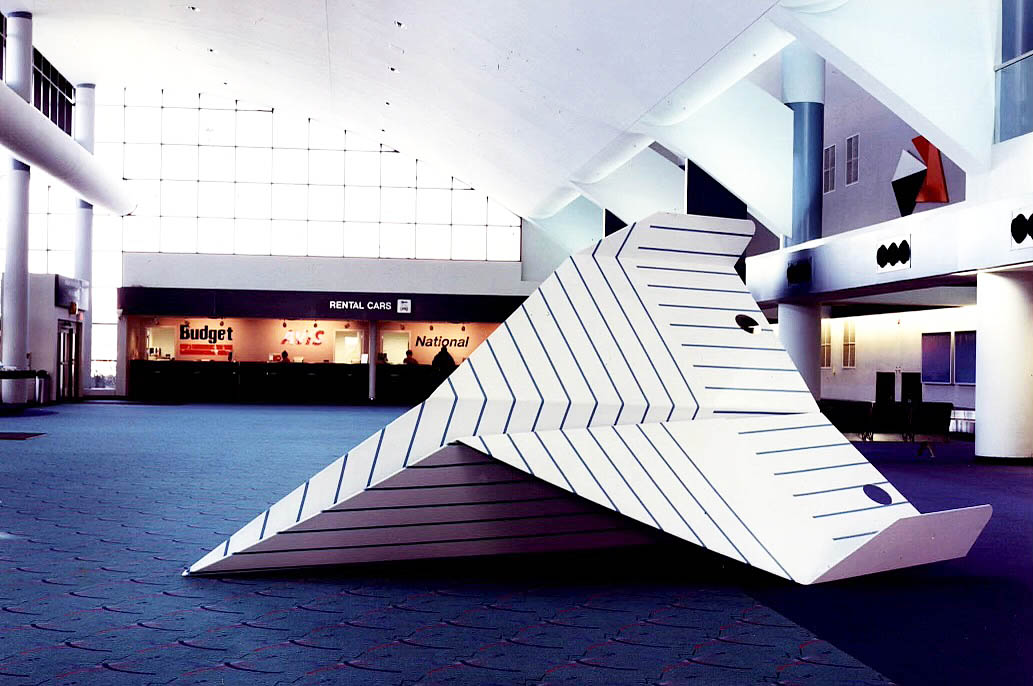

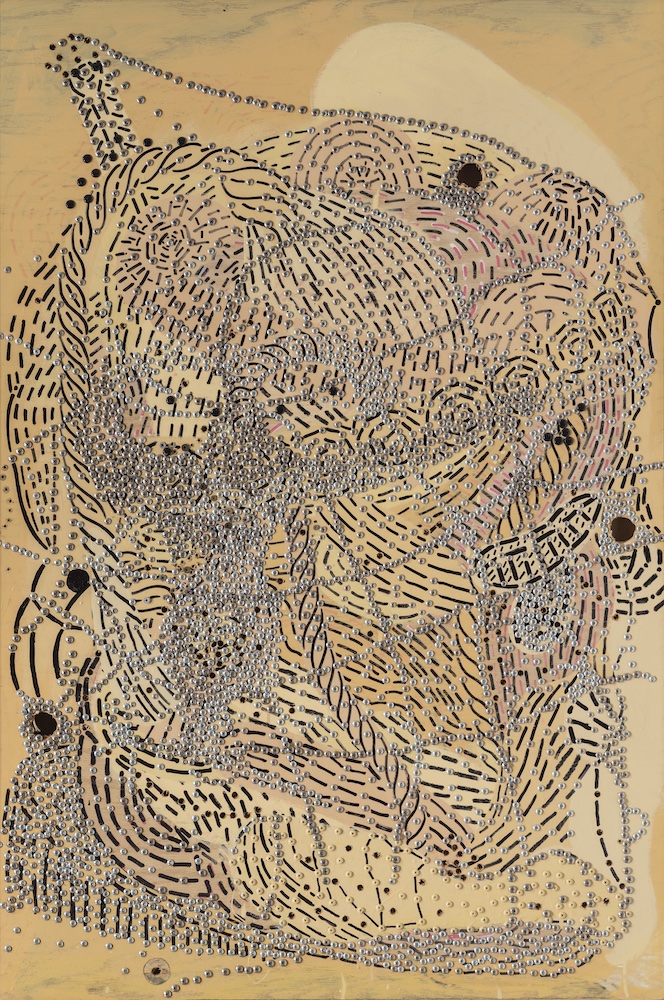

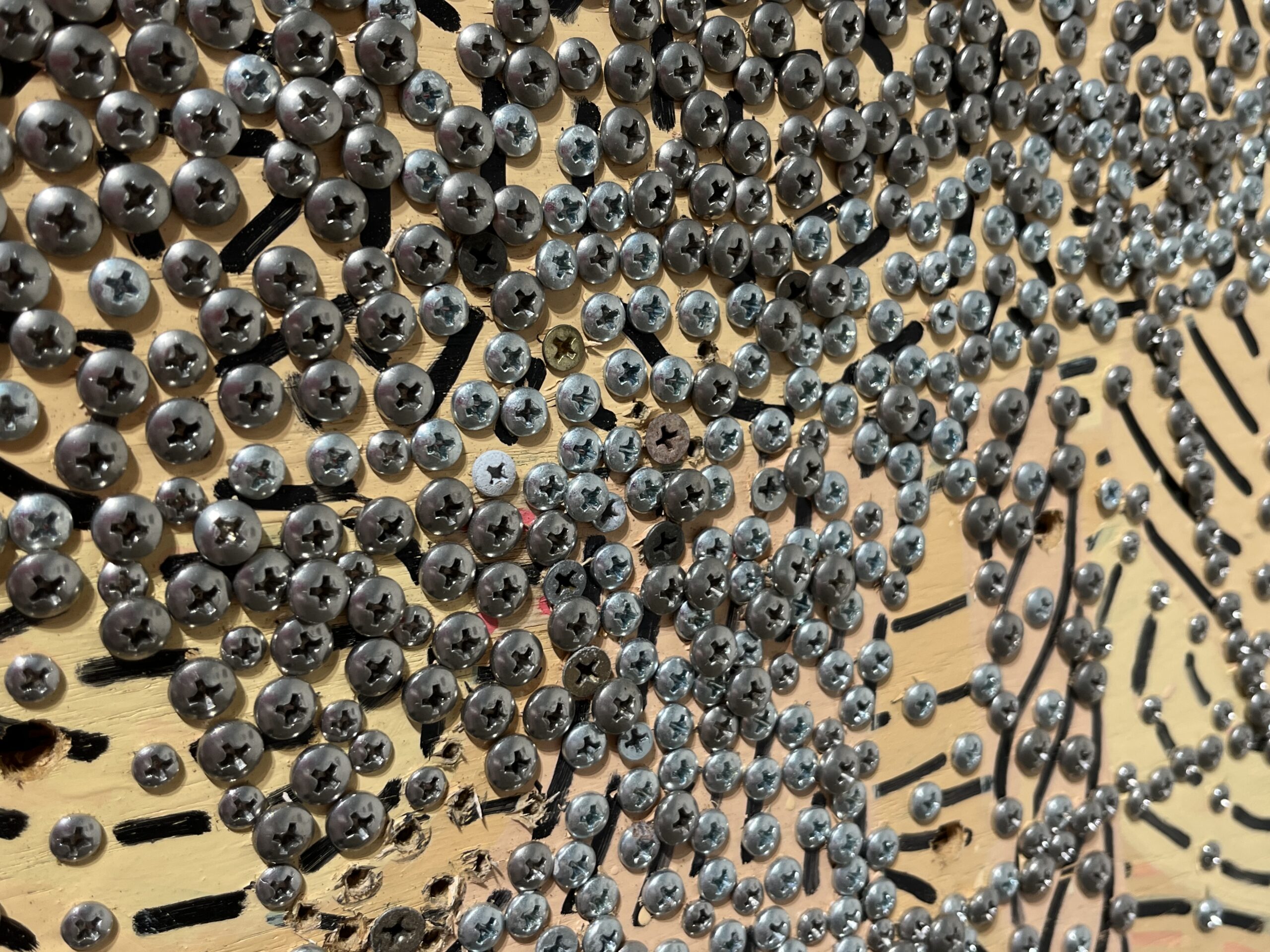

Heloise Pomfret, Installation, small circular objects on plywood.

The work in this exhibition reflects the varied mediums and materials that Pomfret employs to explore her personal psychology in paintings, installations, and ceramic objects. A large piece of plywood displayed in the center of the gallery demonstrates yet another approach, reflecting the diversity of the artist’s aesthetic means. These circular stitched and scratched smaller pieces reflect the translation of her emotional impulses into physical form, “The Brain” is a delightful and multifarious collection of original objects, literally unlike anything this writer has seen.

Heloisa Pomfret is a Brazilian-American interdisciplinary visual artist. She earned an M.A. and an M.F.A in Painting/Drawing from Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan. She also earned a bachelor’s degree in journalism from Casper Libero College in Sao Paulo, Brazil.