Installation image of Al Held at David Klein with “Orion V,”1991, Acrylic on canvas,198”X192” and “Duccio VIII,” 1991, Acrylic on canvas, 108”X108” Photography provided by Robert Hensleigh

In 1979 Detroit’s Cass Corridor art scene was thriving and, while he didn’t represent what was to become the iconic Cass Corridor aesthetic, Wayne State University painting professor John Egner was making interesting art. It was that year that he painted “Burnt Umber,” which eventually was purchased by then Director of the Detroit Institute of Art, Fred Cummings, and hung in the administrative offices of the Detroit Institute of Arts for a while before eventually hanging in the Modern Galleries. “Burnt Umber” is a monumental sized, stunning oil painting of almost spiritual implications, that bridges hard edge geometric abstraction and abstract expressionism with an interesting optical element as well. Incredibly energetic and busy, it was a unique painting for the Detroit art scene and was the centerpiece of Egner’s solo exhibition at the Susanne Hilberry Gallery. It was a very visible painting to all who lived in the Cass Corridor. It was in fact a painting that inspired poets to write poems and this poet to begin writing about painting.

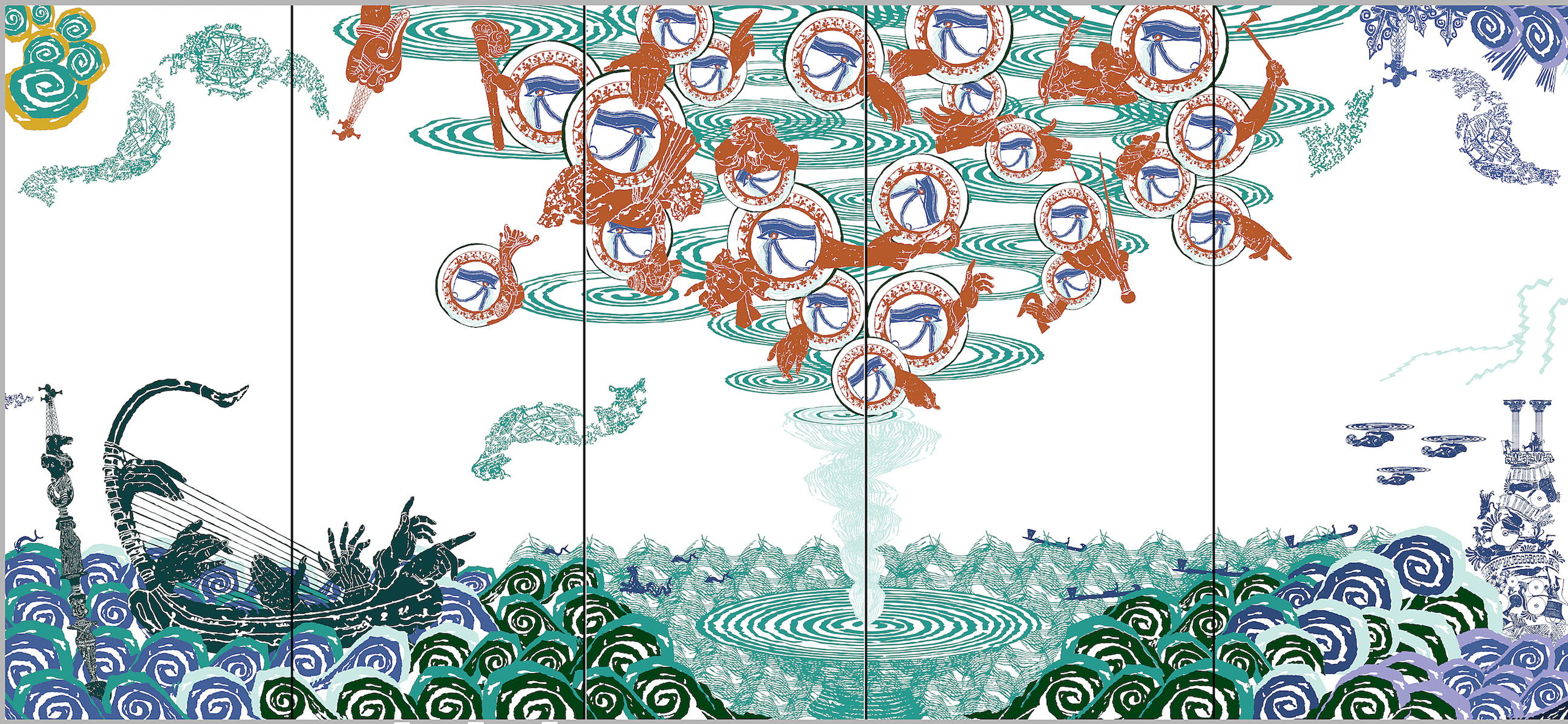

Al Held, “Geocentric IV,” 1990, 96”X144” and “Scand III,” Acrylic on canvas, 72”96”

Walking into the Al Held exhibition at the David Klein gallery this week, it was overwhelming to experience the imposing presence of his geometric abstract painting, “Orion V,” 1991. Immediately reminiscent of Egner’s big painting of nearly 40 years ago in its monumentality (actually the same size) it is what a Renaissance painting is supposed to be and do. Like Egner’s it is awe inspiring. Like the constellation Orion’s prominence in the night sky itself, the painting demands immediate attention and defies immediate description. Of course, like the constellation the painting looks nothing like Orion the hunter, after whom it was named, but you make it fit because that is what Held called it. It is ripe with all manner of geometric shapes and perspectives—instead of angels, cherubs and saints, hollow cylinders looming out of a distant sky, a quixotic, puzzle-shaped plane of vibrant orange, concentric rings floating in imagined ether, a pure purple triangular wedge—in fact other than a distant blue sky-like back drop, the colors seem purposely mystifying and the composition is anything but modern. The acrylic paint is seamlessly laid on like powder-coating on a custom car. Because of the strange, bottomless, topless, perspective the viewer is somehow disembodied amidst the gyre of movement in the painting. Held was inspired by the abstract formulations of Mondrian but because Mondrian was firmly planted on earth, with a stubborn horizon that wouldn’t let him escape, he eventually painted with horizontal and vertical lines. Inspired by Renaissance conceptions of the universe, Held was out in the universe where there is no up and down or in and out, and “Orion V” describes that.

Al Held, “Umbria XXIV,” 1992, watercolor on paper, 49”X 56 ½” and ”Primo V”, 1990, watercolor on paper, 49 3/16” X 57 ½”

Because of its title “Orion V” might be read metaphorically. It could be a celebratory image related to space travel, certainly prominent at the time, but, more likely it could simply be a secular version of the Renaissance vision. Defying famed art critic Clement Greenberg’s prescriptive ideas of flatness, “Orion V” thrives on and exhilarates in the illusion of deep space. It combines the minimalist elements of simple geometry with a hallucinatory landscape.

Another big canvas, “Geocentric IV,” 1990 is more readily grounded in nature, with an emerald green backdrop composed of hollow cylinders, cubes and triangles of heated up primary colors. With a title that sees the earth as the center of the universe, “Geocentric,” a confection of kitschy colors explodes this onslaught of primary forms, reductively standing in for the fundamental forms of nature. A tsunami of these primary forms seems to hurl toward us from a single point in the upper right hand corner. A collection of pinkish-brown cubes in the distant background serves as a substratum (earth?) for the foreground’s explosion of the primary forms. Held spent 1981-2 in Italy at the American Academy studying Renaissance painting and it could be that “Geocentric IV” is as close to a religious painting as he ever painted. Or perhaps more akin to a “Big Bang” Creation myth image, cascading, fluorescing red cubes join with brilliant blue cylinders surrounding a brilliant yellow triangle, cone and cube floating off into space. The classical compositions are unmistakable.

The remaining two paintings are also composed of a multicolored, seamlessly painted, arrangements of triangles, cubes and cylinders, and while they abound in hard-edged geometric shapes, there is a sense of an expressionistic energy behind their composition. There is a playfulness, then, in Held’s painting and brings with it a challenge to sort out perspective and the arrangement of shapes as if in a wilderness composed of a forest of forms.

The backrooms of the gallery include eight watercolors and a black and white painting. It is difficult to compare them to the acrylic painting but they are, it seems, from where the title of the exhibition, “Luminous Constructs,” is derived. Quite simply they exude light as if lit from within. “Umbria XXIV,” 1992, which probably takes its title from Held’s travels to Umbria, the magnificent Italian region of natural beauty and culture, is composed of a brilliant tangerine-orange, cruciform shape, constructed of various sized rectangular forms. The floor, the only reference to a built space in the exhibition, is emerald green and yellow checkered and the cruciform, has red, halo-like rings floating above and around it. The transparent glow of the watercolors give them an immediate, sketch-like or cartoon but sure-handed quality. Of course, the imagery of the forms are Held’s play on Christian iconography.

When John Egner was an entering art student at Yale University, he was placed at Al Held’s interview table. Egner told Held that he was there specifically to study with famed Abstract Expressionist Jack Tworkov. Held called over to Tworkov’s desk and said “Hey Jack this one is for you.” Egner got up and went over to Tworkov for the interview. Years later Egner told me, “I guess for many years at least if I was asked who was my favorite painter I would have replied “Al Held.” A little Detroit art history to go with a vibrant and rare view of an American master.

Al Held, “Victoria VIII,” 1991, watercolor on paper, 43 5/8” X 49 ¼” and “Plaza IV, 1993, watercolor on paper, 49 ¼”X63”

Al Held one-person exhibition at the David Klein Gallery through April 28, 2018