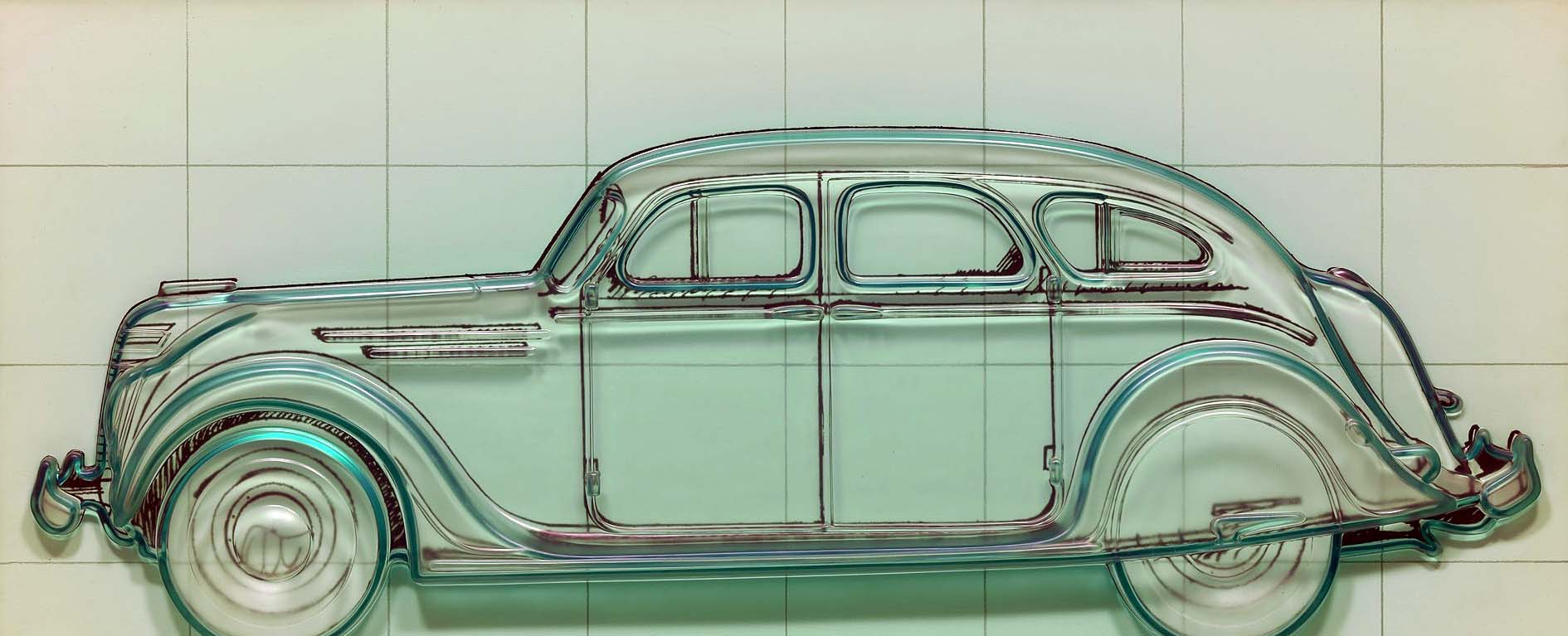

Claes Oldenburg, Profile Airflow, 1969. Cast polyurethane relief over lithograph. Collection of Flint Institute of Art

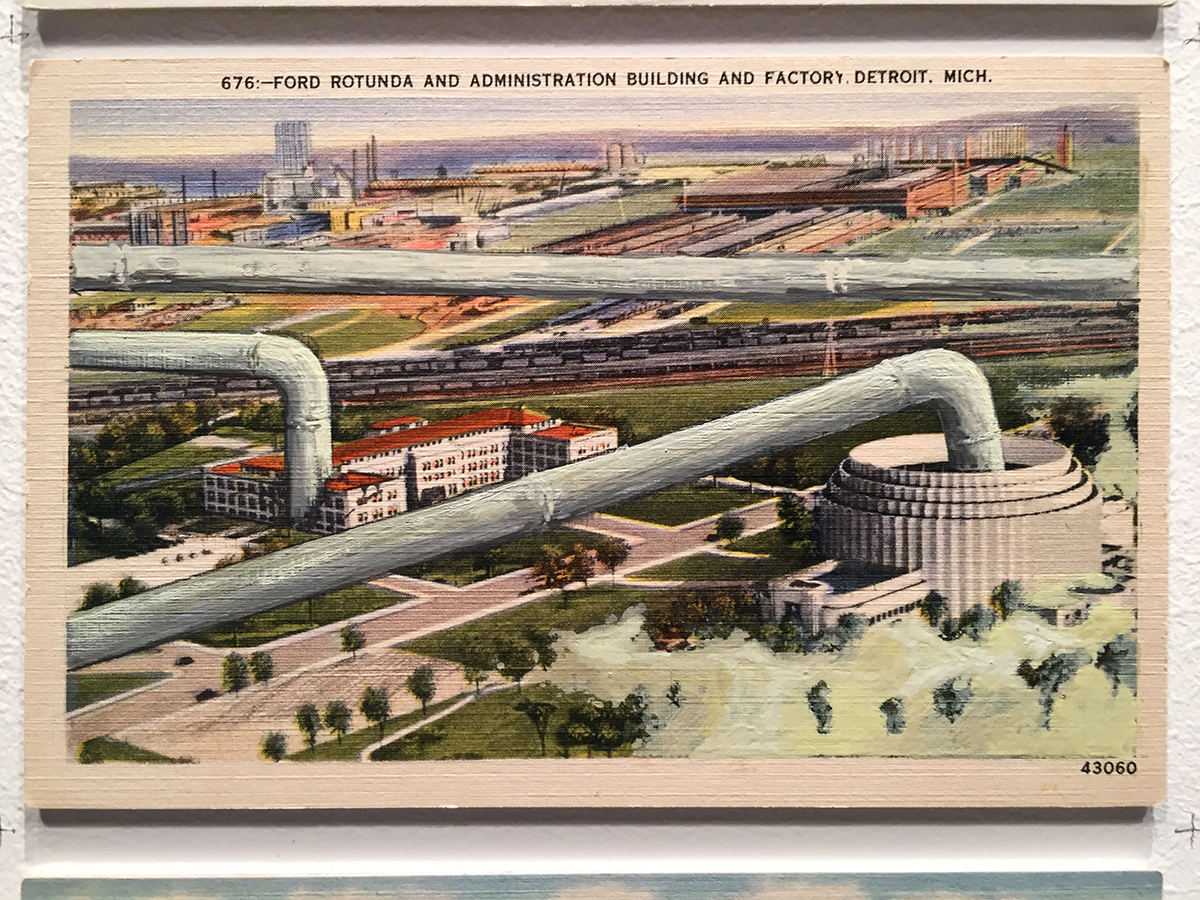

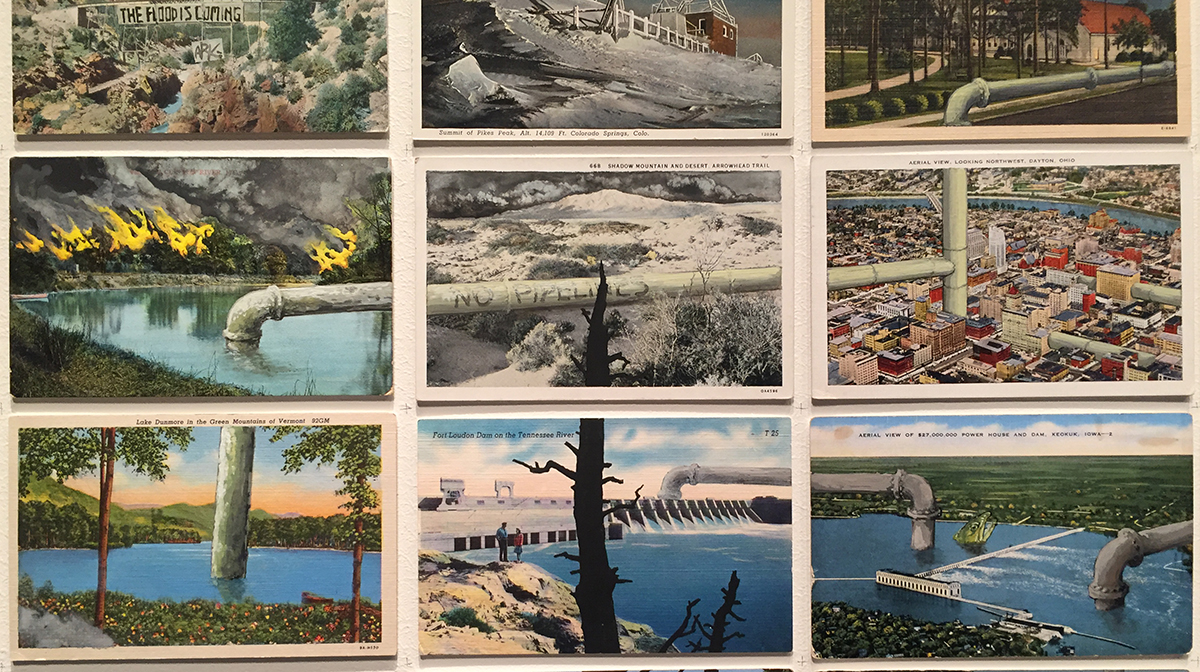

For those of us who grew up with the automobile as a ubiquitous part of life, the very prevalence of which (like oxygen) perhaps makes it go largely unregarded, it’s worth giving pause and considering the revolutionary, democratizing effect of the advent of the automobile, a cultural paradigm shift which literarily and figuratively reshaped the 20th Century American landscape. The automobile takes center stage in the Toledo Art Museum’s exhibition Life is a Highway, the first U.S. exhibition to explore the automobile’s influence on visual culture, with specific attention to the Midwest. This is not just a show about automobile-inspired art, but it manages to offer some commentary on both the celebrated advances of 20th Century technology and on the social and labor injustices that accompanied them.

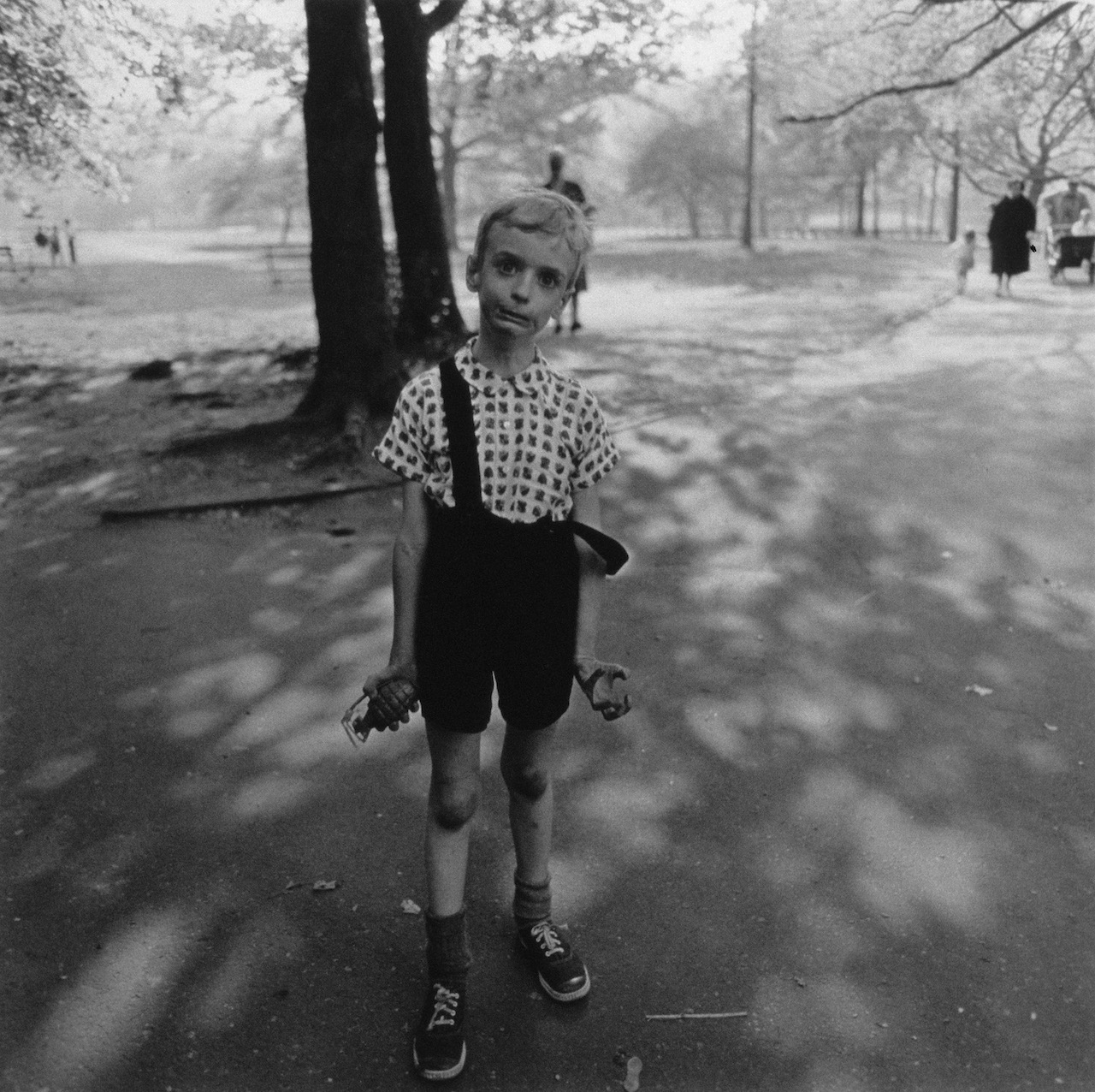

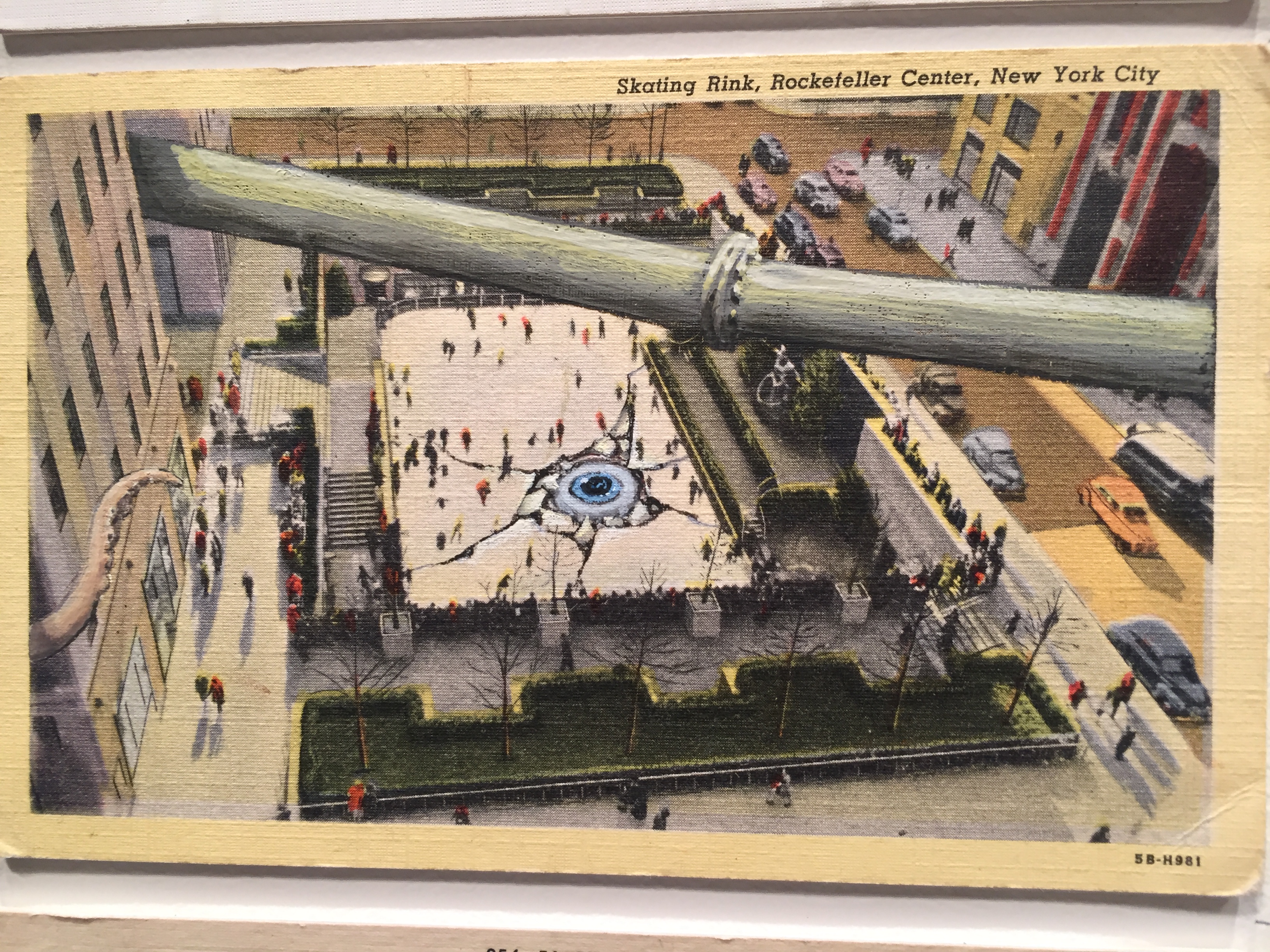

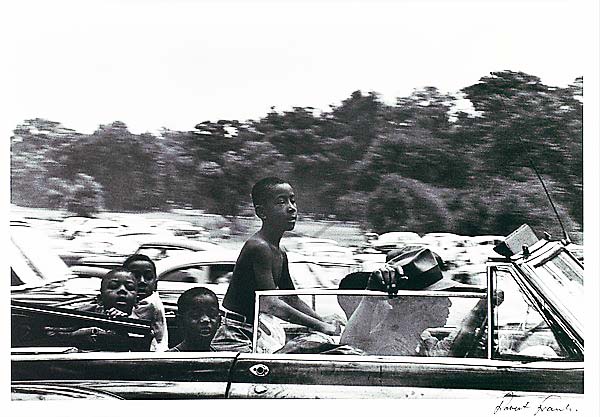

Robert Frank,Belle Isle, Detroit, 1955. Photograph. Collection of MFA Houston

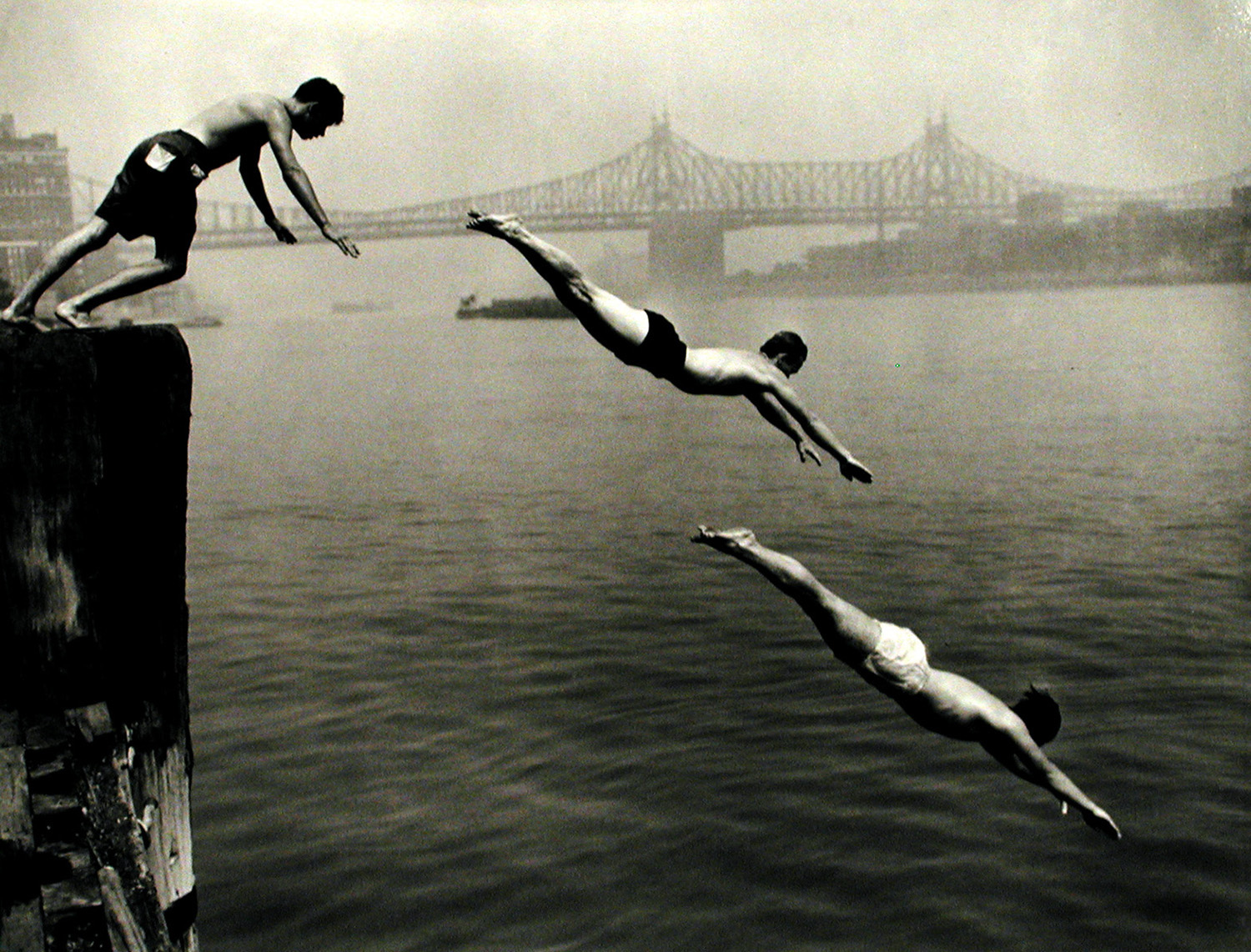

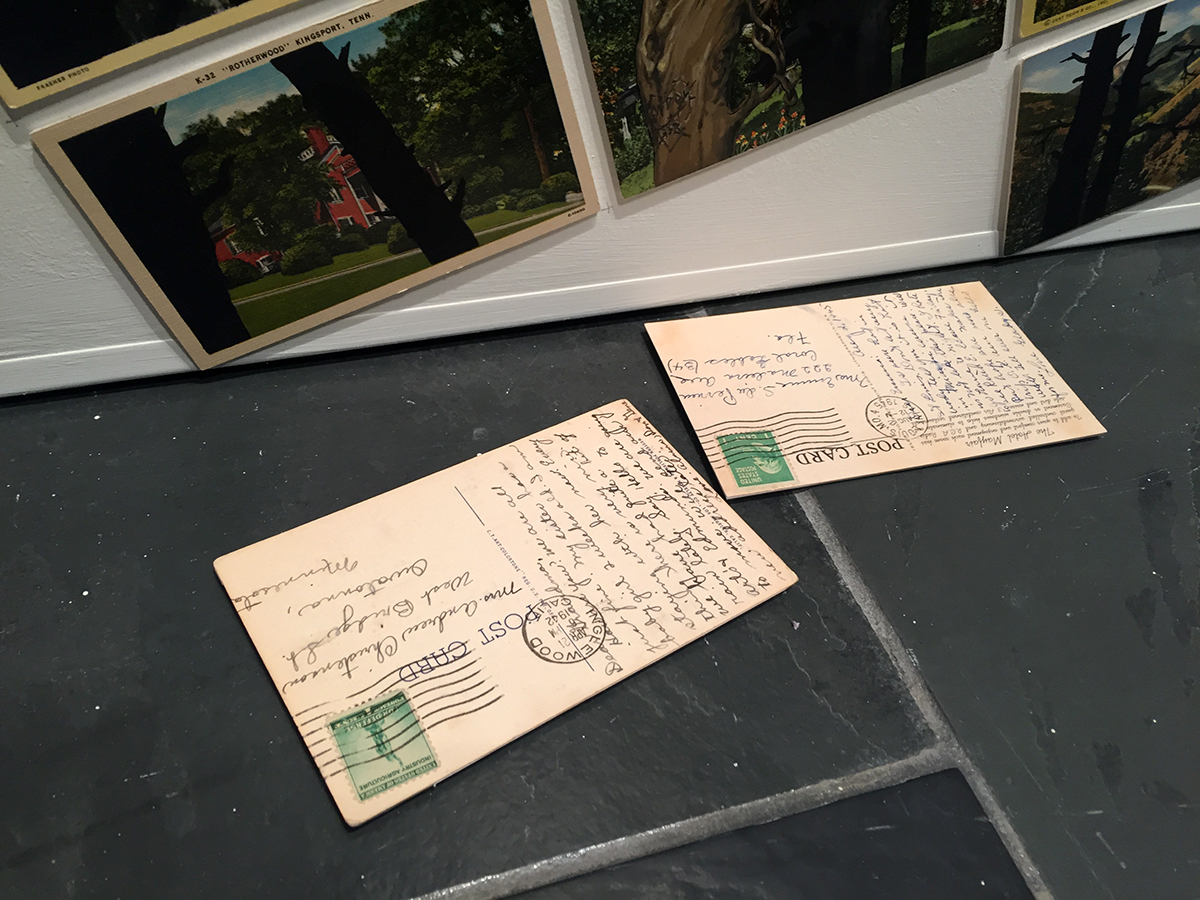

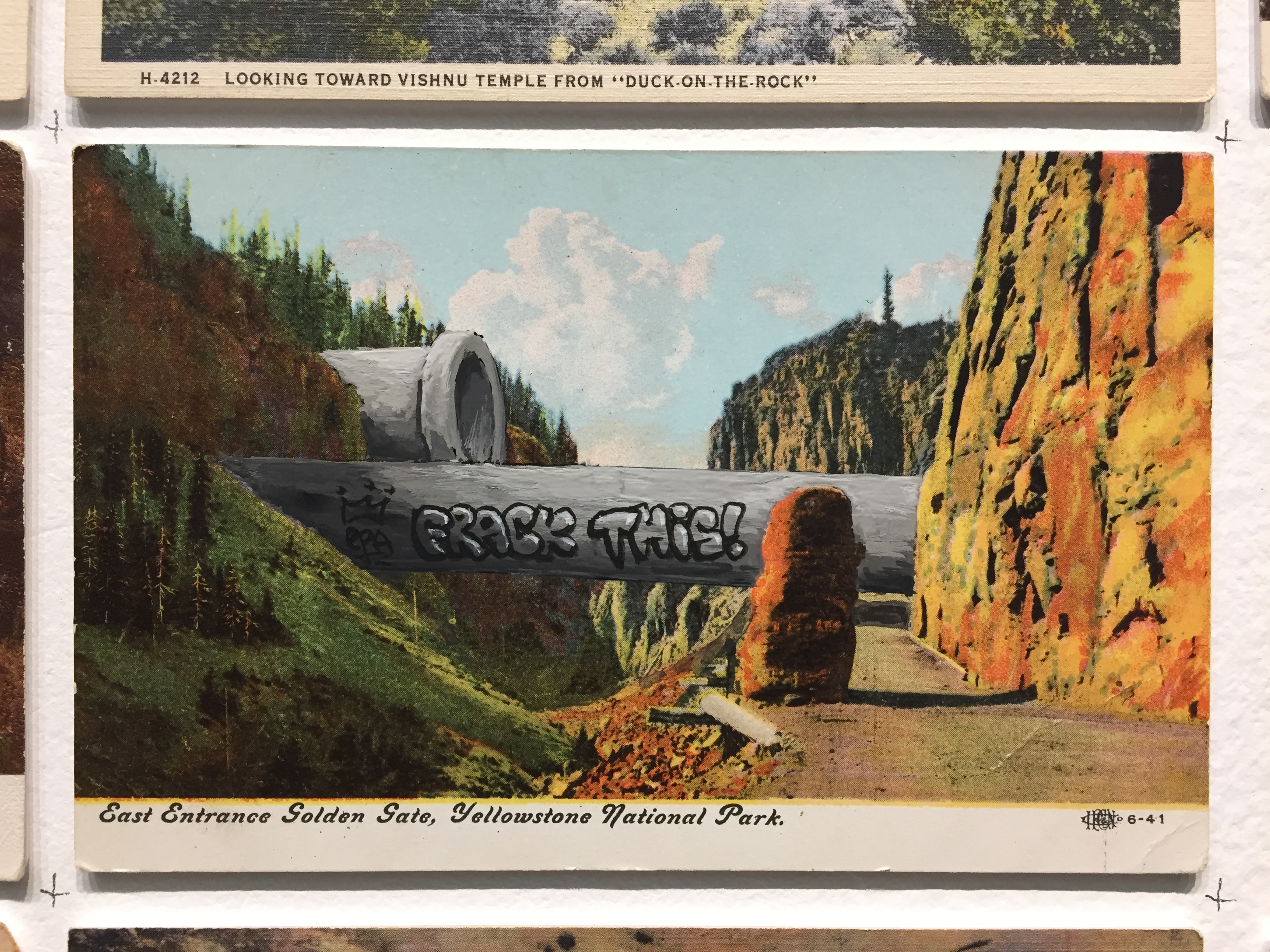

Life is a Highway assembles over 150 works spanning a diverse array of media, though photography seems to dominate the gallery suite. Road signs and traffic cones, in addition to offering playful ambiance, guide viewers through the show. Arranged chronologically, the exhibition opens with images that suggest the optimistic spirit with which the automobile became an American symbol. A lithograph by Thomas Hart Benton shows the Joad family (from Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath), rendered in Benton’s characteristically folksy style, packing their belongings into the rickety-looking pickup truck which will transport them from the Oklahoma dust bowl to a better life (or so they think) in Edenic California. But a looping video from Charlie Chaplin’s iconic film Modern Times suggests the cost on the human spirit of the age of the assembly-line and the automobile; Chaplin’s character must perform menial tasks on an implausibly fast assembly line, his body itself reduced to a mere machine. And while the crisp paintings and photographs of Charles Sheeler celebrate the sublime grandeur of modern industrial temples (his ant’s-eye perspective reminiscent of the etchings of Piranesi’s views of Roman ruins), Arthur Siegel’s bird’s-eye view of a labor strike offers a different perspective, literally, on industrial progress.

Life is a Highway, Installation image, TMA 2019

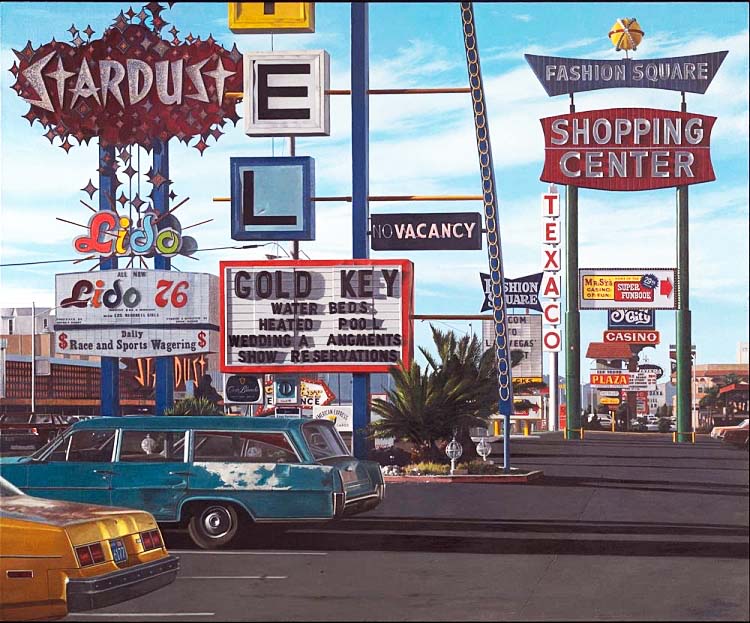

After the Second World War, the automobile increasingly became both necessity and status symbol, and the American landscape changed to accommodate its omnipresence in American life. Robert Brown humorously approaches this with a painting of a cartoonified map of America in which every inch of earth has become occupied with shopping centers and parking lots. In contrast, the photographic pencil drawings of Charles Kanwischer suggest that there really is an understated sublime beauty in the industrialized American landscape: the columns of his US 24 Road Project (presumably meant to support a bridge) here against a barren landscape seem like ruins from an ancient civilization, the Minoan palace of Knossos, perhaps. And Catherine Opie’s photographs of highway overpasses, rendered in elongated horizontal prints, are exquisite examples of 2D design, and one doesn’t even recognize these as roads at first, such is her ability to show the beauty in what we might consider the mundane.

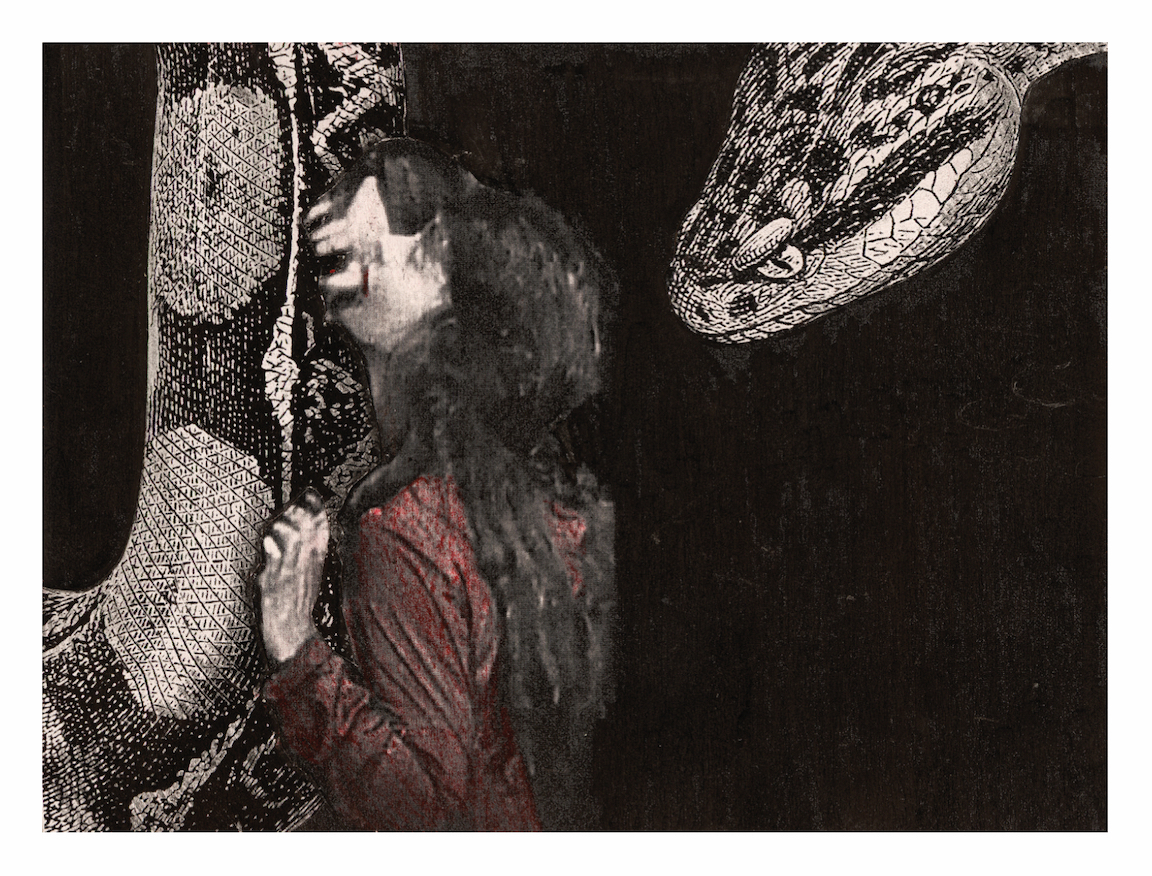

But while the automobile became a symbol of freedom for many, the exhibition also turns its eye to the racial injustices painfully prevalent in automotive America. Well into the 1960s, many restaurants and hotels refused service to people of color, necessitating the Green Book, a travel guide authored by Victor Hugo Green which listed establishments deemed safe for African Americans travelling in the Jim Crow South. Several Green Booksare on display, alongside photographs from Jonathan Calm’s series Journey Through the South: Green Book, for which Calm traveled through the deep south, photographing locations from the Green Book as they appear today (some are now just vacant lots). Among the establishments is the Lorraine Motel, which played host to, among others, Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, and Dr. Martin Luther King the fateful night he was assassinated.

John Baeder, Stardust Motel, 1977. Oil on canvas. Collection of Yale University Art Gallery

Perhaps those who grew up during the pervasive automobile culture of the 50s and 60s, when cars had a Baroque lavishness entirely unburdened by any regard for efficiency, will find this exhibition especially resonant. But one certainly doesn’t have to be an automotive know-it-all to appreciate Life is a Highway, which manages to be interdisciplinary in its scope, touching at once labor history, social (in)justice, economics, the environment, and so much more.

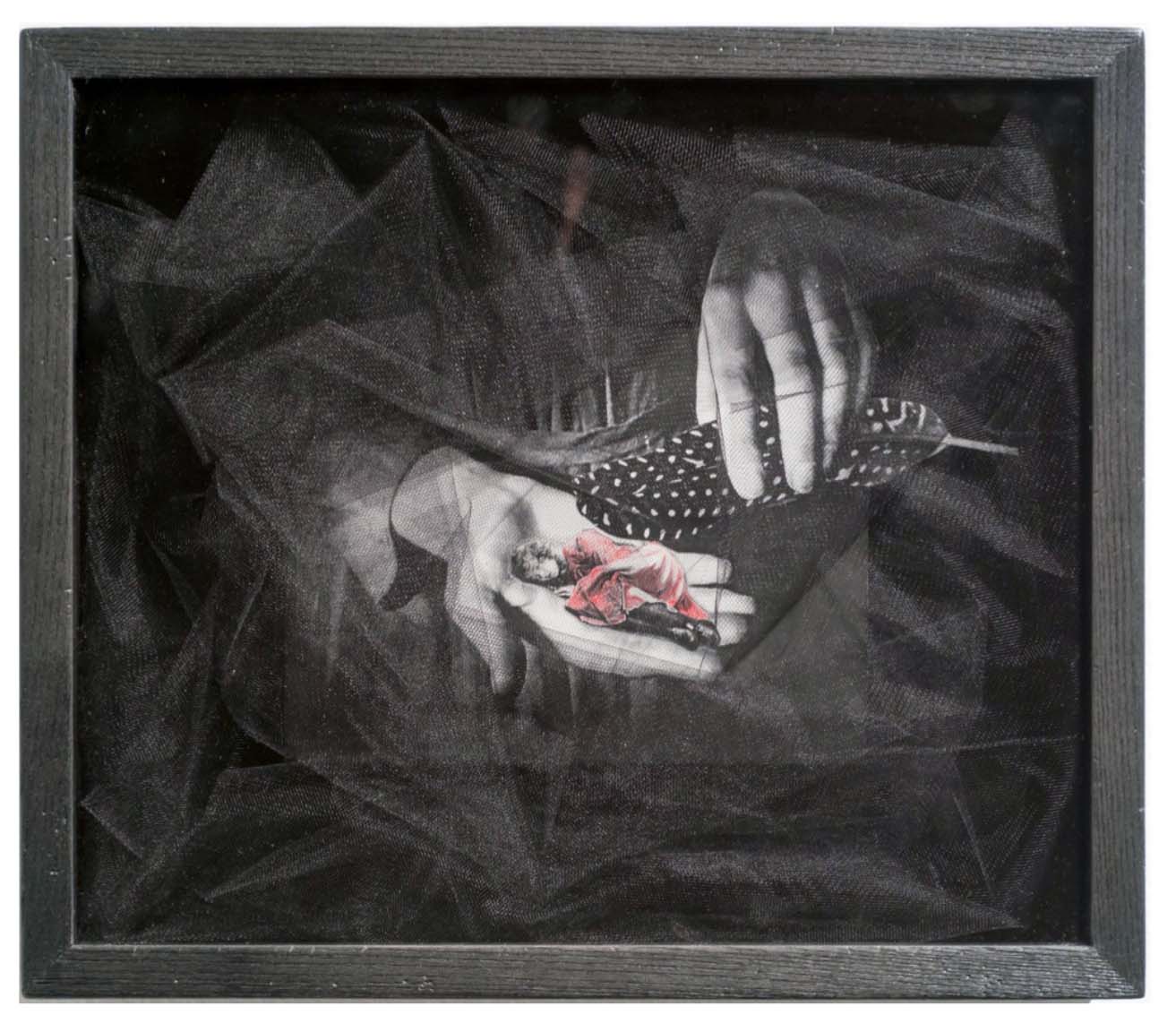

In addition to Life is a Highway, the TMA is concurrently exhibiting a vibrant show in its newly re-opened new-media gallery suite. Everything is Rhythm is a multisensory show which explores intersections between music and the visual arts. The show pairs fourteen paintings with corresponding works of music, which viewers can listen to by plugging in headphones (provided by the museum) into ports located at listening stations scattered throughout the gallery suite. The exhibit gently challenges preconceptions of what an art exhibit ought to be, and in its tactful paring of image and sound manages to achieve an effect best described as cinematic.

In most cases, the pairings reflect a direct relationship between the composer and the painting. Harold Budd’s 1996 album Luxaserved as a musical tribute to some of his favorite artists, such as Anish Kapoor and Serge Poliakoff. Here, his airy, meditative, and sinuous electronic composition Agnes Martin seems an apt musical interpretation of the British painter’s work, characteristically space and serene. Composer Morton Friedman very much admired the paintings of Mark Rothko, and in 1971 even composed a moody and somber instrumental and vocal composition for the equally moody and somber Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas. For this exhibit, an untitled 1962 Rothko is paired with Friedman’s Madame Press Died Last Week at Ninety, a morose symphonic work which rhymes with the tragic emotion Rothko so ardently tried to convey in his art.

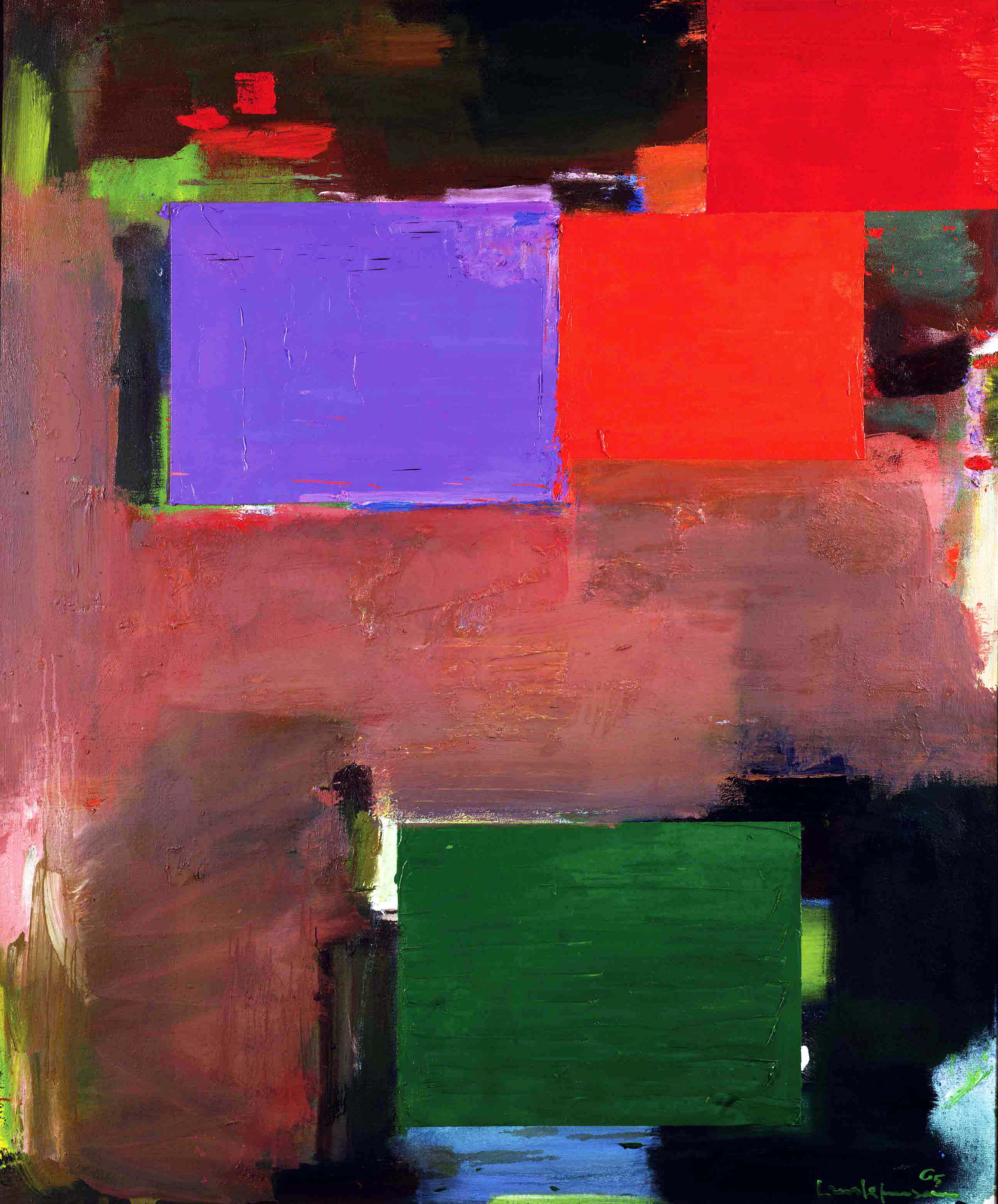

Hans Hofmann (American, 1880-1966), Night Spell, 1965, oil on canvas, 72 x 60 in. (182.9 x 152.4 cm), Toledo Museum of Art (Toledo, Ohio), Purchased with funds from the Libbey Endowment, Gift of Edward Drummond Libbey, 1970.50

Some pairings emerged as curatorial decisions, regardless of whether or not the respective artists and musicians were conscientiously responding to each other. While admittedly quite subjective, the pairings seem to work quite well. The soulful, improvisatory trumpet of Miles Davis is paired with Hans Hofmann’s abstract expressionist Night Spell, itselfthe product of improvisation and intuition. And the myriad of rhythmic vertical lines in Julian Stanczaks And Then There Were Three, a spellbinding tour de force of the Op Art movement, seems the logical visual equivalent of the hypnotic repetition of Philip Glass’ Metomorphosis III, a solo piano work which, while repetitive, manages to be undeniably beautiful, much like ocean waves breaking on the shore.

Everything is Rhythm, Installation, TMA 2019

Everything is Rhythm is a delightful show. It’s also a great introduction to abstract art for those who dislike abstract art. After all, music is abstract insofar as it’s transient and ephemeral, and we can appreciate an instrumental work even if it’s not about anything in particular, but merely succeeds in evoking a certain mood. Over a century ago, American artist James McNeil Whistler advanced the argument that the same ought to be true for the visual arts, and he began giving his increasingly abstract paintings musical titles (arrangementsand nocturnes). Were he to magically time travel to the present day, he’d certainly view this exhibition approvingly.

Life is a Highway at the Toledo Museum of Art runs through September 15, 2019, and Everything is Rhythmis on view through February 23, 2020.