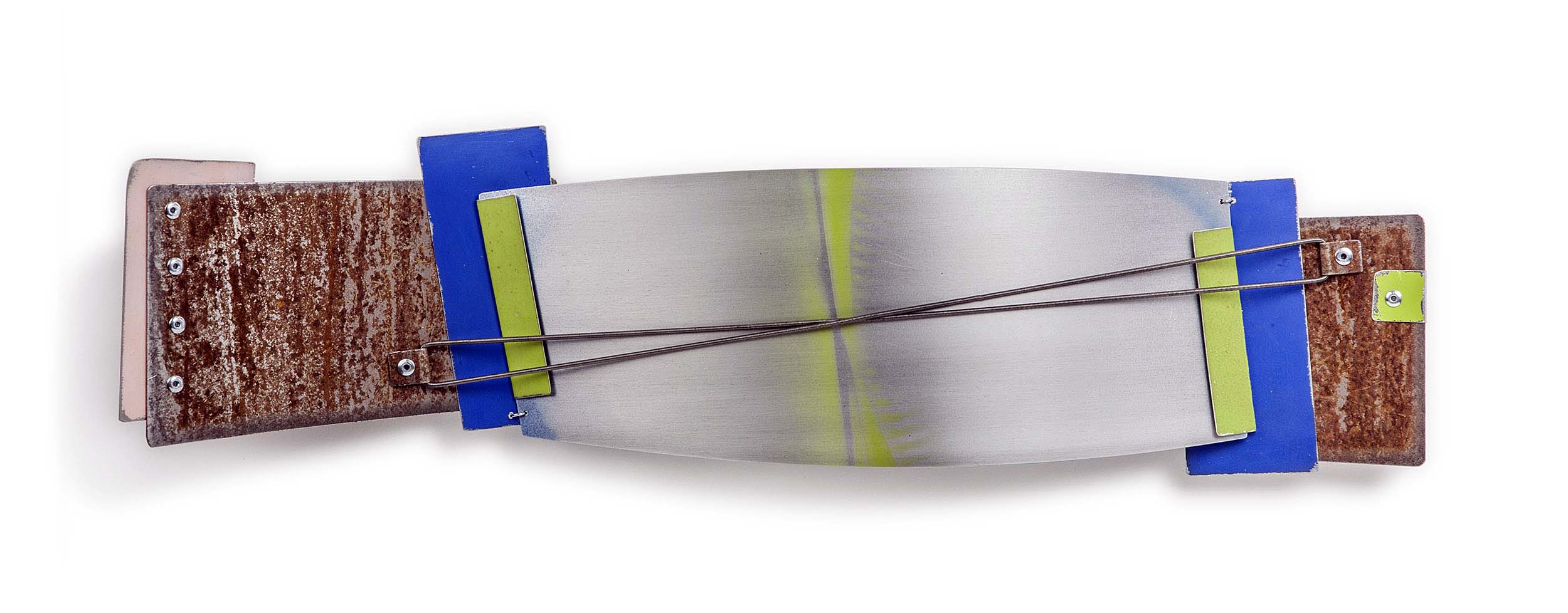

Miss Hiroshima and Miss Osaka Installation, 2023. All images courtesy of Ashley Cook

On December 2, 2023, the Detroit Institute of Arts celebrated the opening of a new exhibition that features five unique dolls, handmade by Japanese craftsmen as part of an initiative to build friendly relationships between the children of the United States and Japan. As a response to the Anti-Japanese mentality that was spreading throughout the United States in the late 1920s, American educator, author and missionary Sidney Lewis Gulick formed the Committee of World Friendship Among Children. He collaborated with adults from the United States and Japan, including prominent Japanese businessman Shibusawa Eiichi, to organize an exchange of dolls to teach the children of each culture about each other. The story of the Japanese Friendship Dolls serves as an example of a unified effort to heal the wounds that result from conflicts of cultural difference. It is a lesson on peacekeeping and a reminder of the role that youth hold in the ongoing conversation on diversity and acceptance around the world.

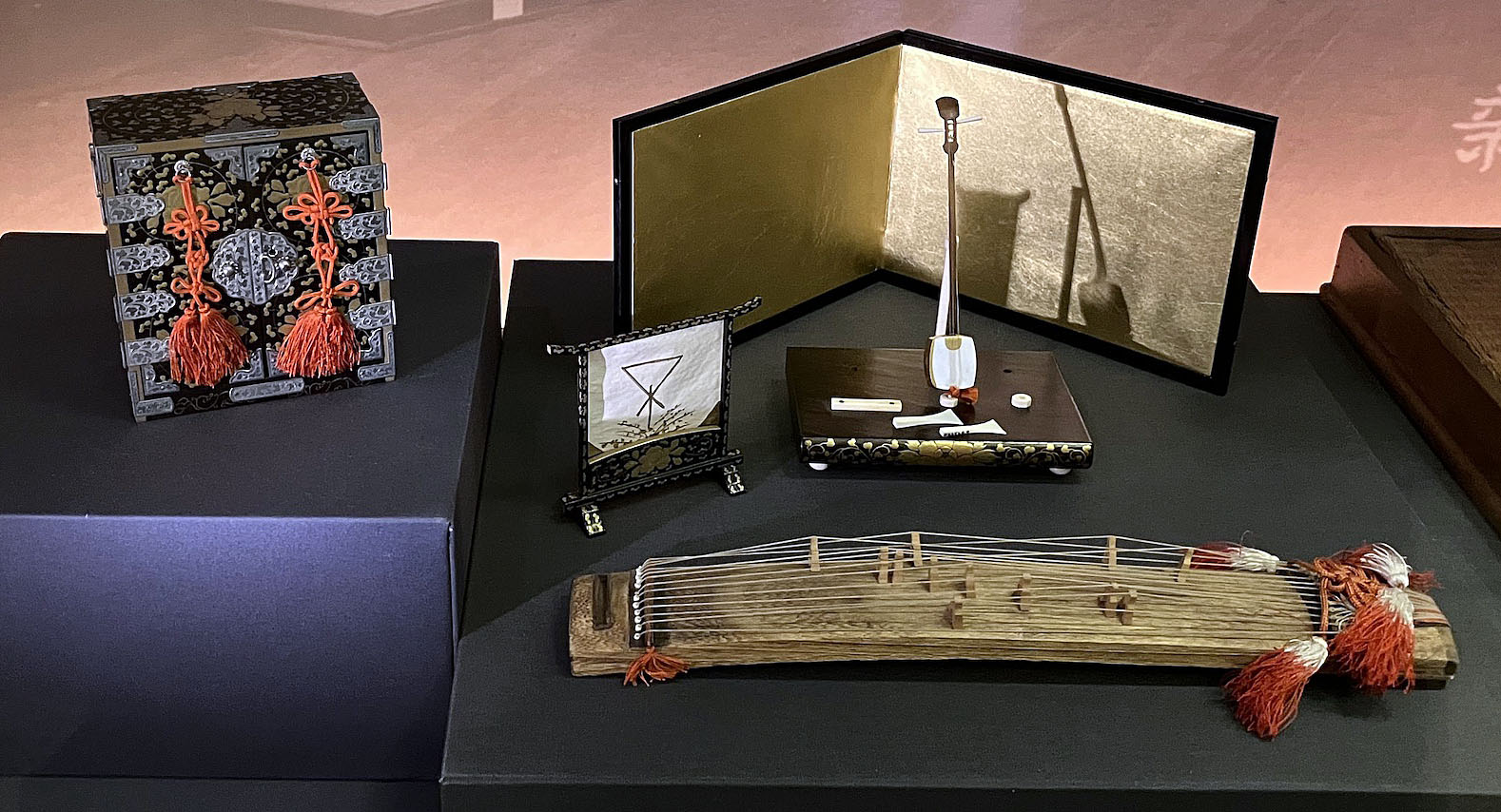

Miss Osaka’s Accessories, 1927.

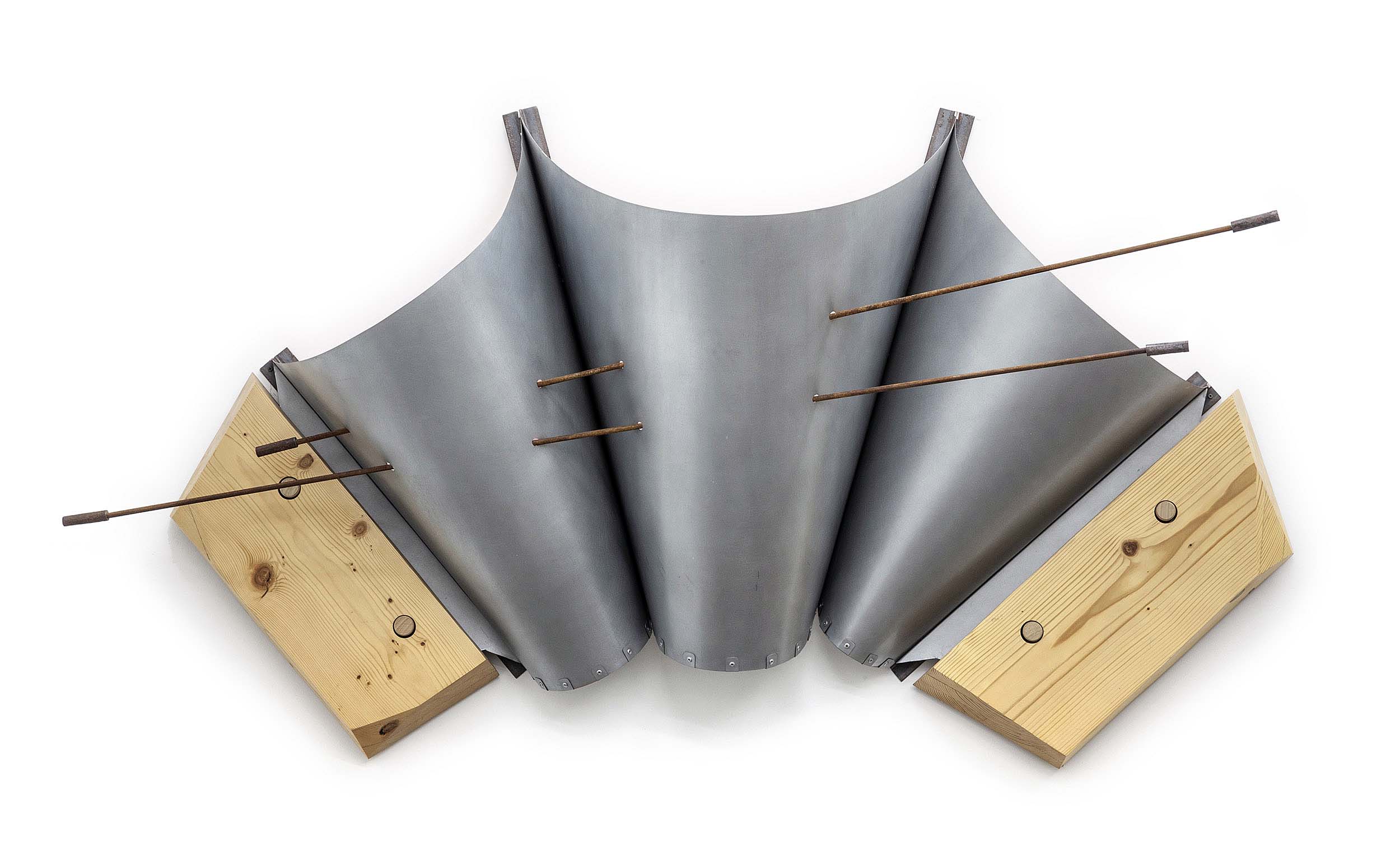

On the first floor of the DIA in the hallway between the Egyptian and Romanesque exhibits are three large windows dedicated to the history of puppetry. Here, guests of the museum are invited to visit Miss Osaka, Miss Hiroshima and Miss Akita, all made in 1927. These traditional Ichimatsu dolls have a white skin-tone and large black eyes. Their fair complexion is achieved through the use of gofun, an art material made of powdered clamshells that was invented in the Heian Period of 12th century Japan. For Japanese-American children living in the United States in the early 20th century, the dolls available did not resemble their physical attributes or cultural heritage. With the Ichimatsu doll being one of the most popular dolls in Japan, they became the template for the 58 Friendship Dolls that were sent as gifts from the children of Japan to the children of the US at that time. Their names, wardrobe, and accessories taught white Americans about the culture of their Japanese neighbors and inspired Japanese Americans to embrace their own heritage with pride.

Miss Hiroshima’s Accessories, 1927

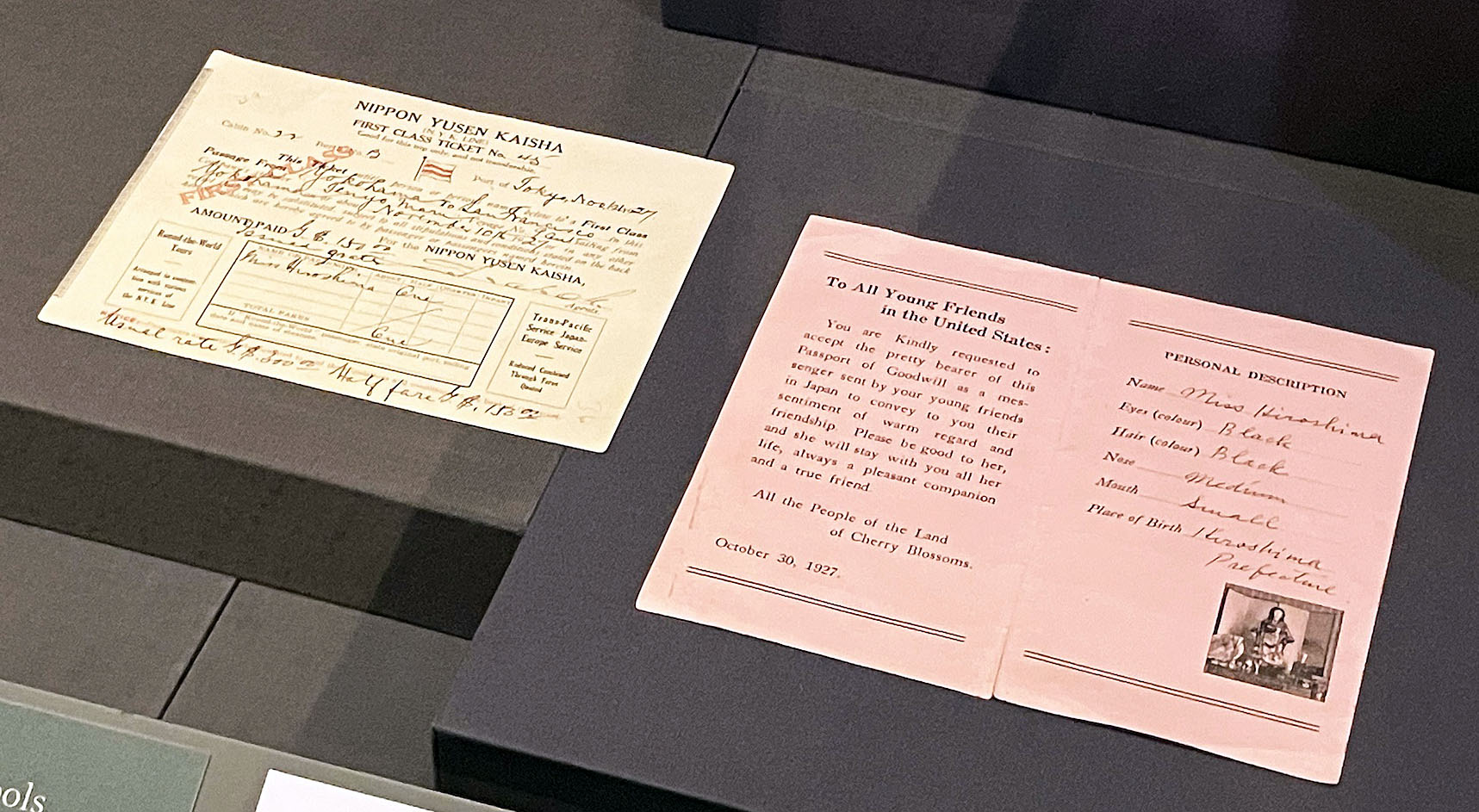

Over 12,000 American Friendship Dolls were also produced and sent across the Pacific to children in Japan as part of this cooperation. While the American dolls were smaller in size and manufactured in an industrialized way, the Japanese Friendship Dolls had unique details and qualities that spoke to the location where they were made. As opposed to functioning as toys for the children to play with, they were sent over as cultural diplomats to share information, promote curiosity and encourage appreciation for Japan. Miss Osaka brings with her a harp, a guitar and a music stand, Miss Hiroshima brings a blue and white tea set and Miss Akita brings a sewing kit. As travelers, each of them also has a clothing chest, a passport and a steamship ticket. Their Kimonos are hand-dyed, outlined with silver or gold and tied with a sash. The tabi socks and sandals complete their formal dress which is worn on special occasions in Japan, communicating to whoever they encounter that they are honored by their presence. The museum provided placards amongst these various elements to further inform its viewership about the relevance of each individual detail.

Miss Hiroshima’s Travel Documents, 1927.

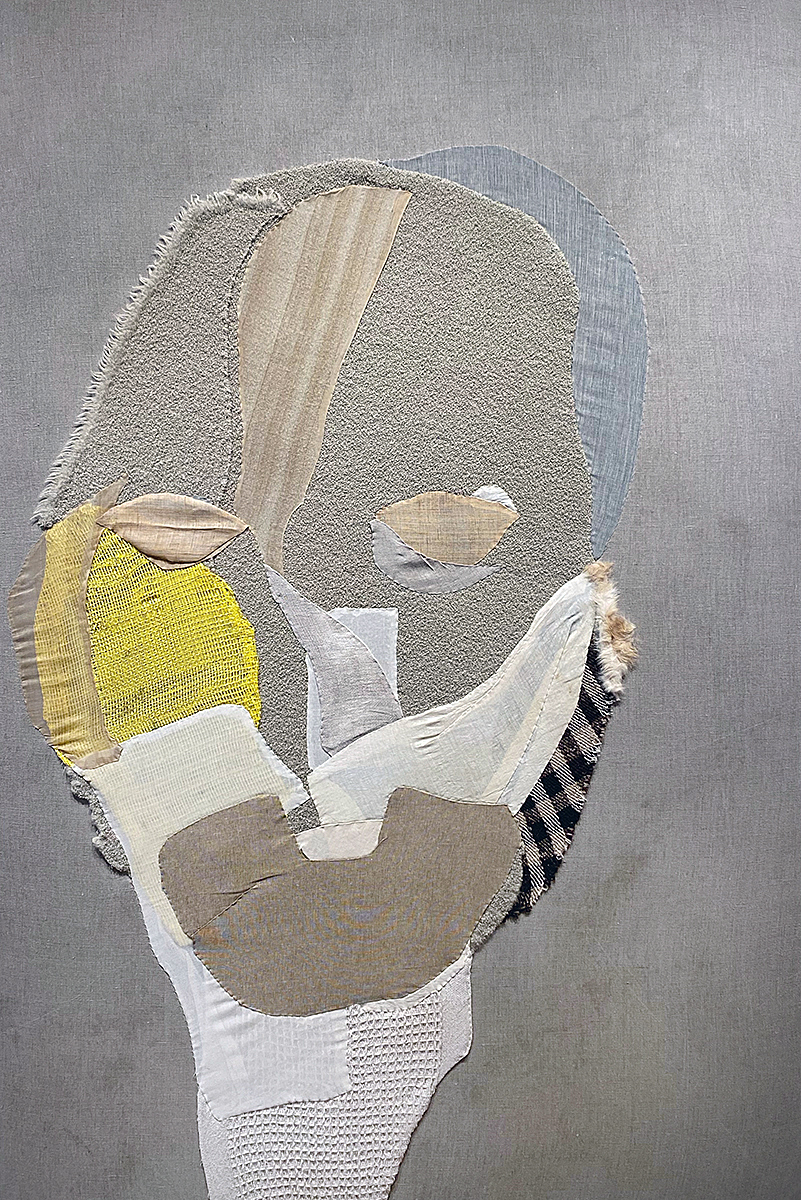

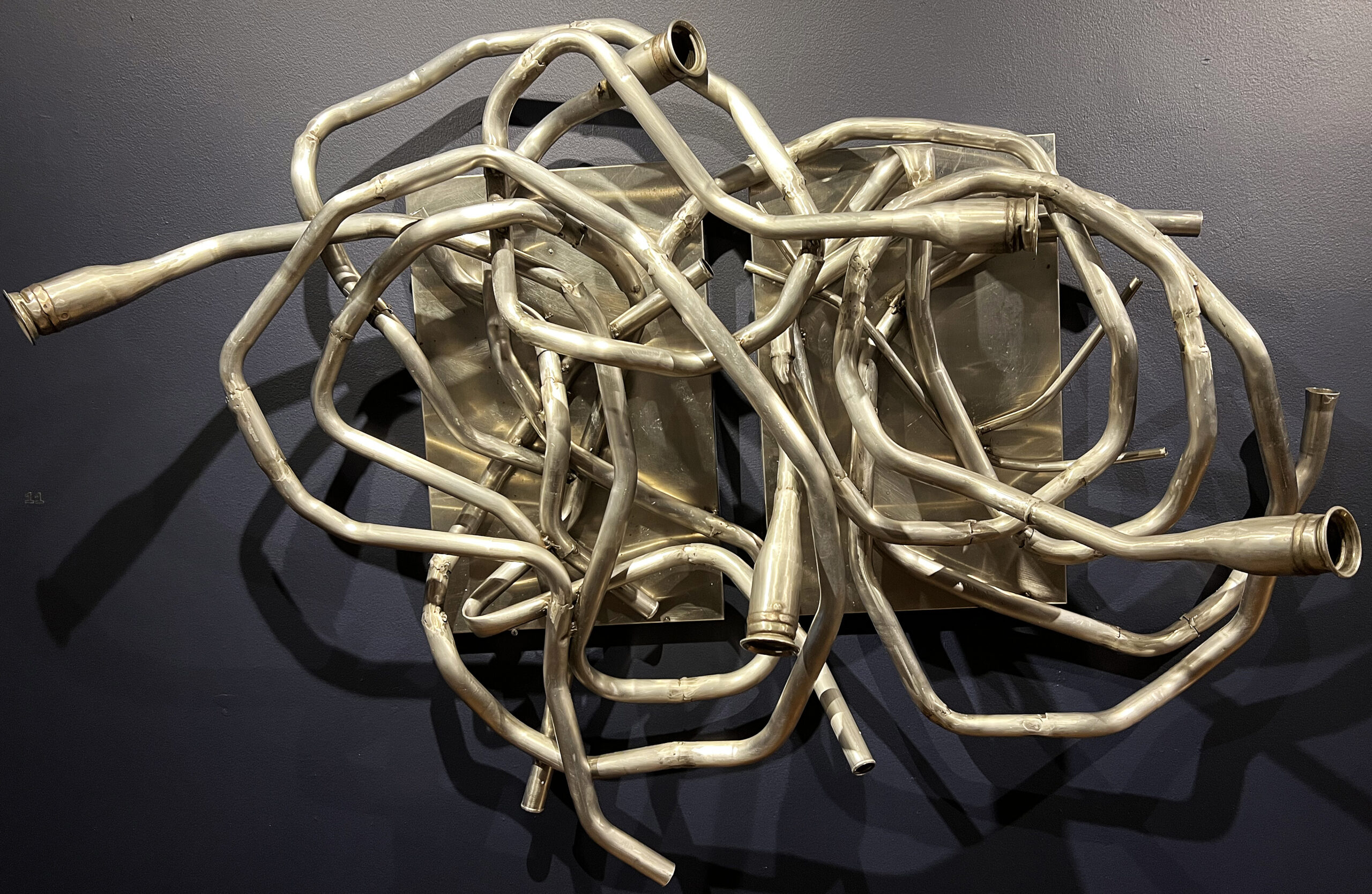

As guests visually traverse the exhibit of delicate figures and their belongings, archival photographs and cross-cultural messages, they are also greeted by Akita Sugi-o, created in the 1930s, and Tomoki, who was created in 2018. As a way to communicate to the boys of Japanese heritage living in the United States, Akita Sugi-o was made in the late 1930s by the same artist who made the aforementioned Miss Akita. Like Akita Sugi-o and the other three dolls, Tomoki demonstrates the long-standing legacy of traditional Japanese doll making and its ongoing presence into the 21st century. He was created specifically for the DIA and arrived complete with accessories including carp flags, a sword and a bow and arrow.

Miss Akita Installation, 2023.

The Japanese Friendship Dolls of the early 20th century, including those included here, toured the United States like agents of peace. Through the literature provided as part of this exhibit, guests have the opportunity to learn about the multifaceted approach taken by The Committee of World Friendship Among Children, who, in addition to producing and shipping the dolls and their accessories overseas, also invited a variety of public arenas to join the “Doll Travel Agency” and receive a visit from a doll. Arrivals and departures were welcomed with celebration followed by reflections and demonstrations that kept their message of goodwill and harmony alive. The amazing artists listed as the makers of these dolls include Kokan Fujimura, Takizawa Koryusai II and Hirata Goyo II. Their exquisite work played an essential role in this effort to bring healing to the Japanese communities of the United States. As an exhibition that directly touches not only on the challenges that come with diversity but also presents potential solutions to those challenges, Japanese Friendship Dolls at the Detroit Institute of Arts serves a valuable purpose beyond leisurely engagement.

Akita Sugi-o and Tomoki Installation, 1927.

Japanese Friendship Dolls at the Detroit Institute of Arts opened in the Founders Junior Council Puppet Case on December 2, 2023, and will be on view until June 5, 2024.

Tomoki’s Carp Flags Accessory, 2018.