“ECHOES” at Galerie Camille is a three-person show featuring the work of Robert Mirek, John McLaughlin, and Paula Schubatis . The show demonstrates points of resonance that carom throughout the individual bodies of work, as well as creating a kind of visual conversation between the three artists, who would seem to have little in common, at first glance.

Mirek and McLaughlin are both established artists with long histories in the Detroit Metro scene. Schubatis is an emerging artist and recent graduate from University of Michigan Stamps School of Art and Design, and has been tearing up the Detroit scene lately, with a turn as a Red Bull House of Art resident, and a number of group and solo shows in the area.

Installation Image, Robert Mirek, Mitosis – All Images Courtesy of Sarah Rose Sharp

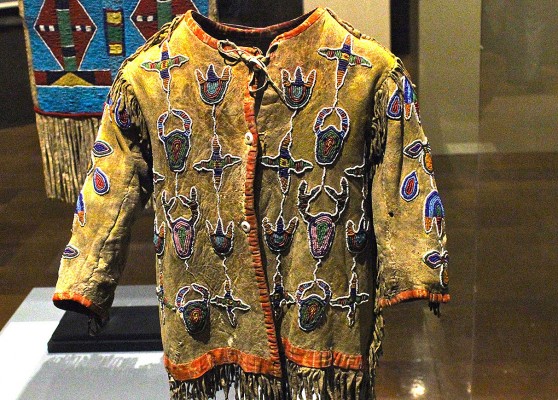

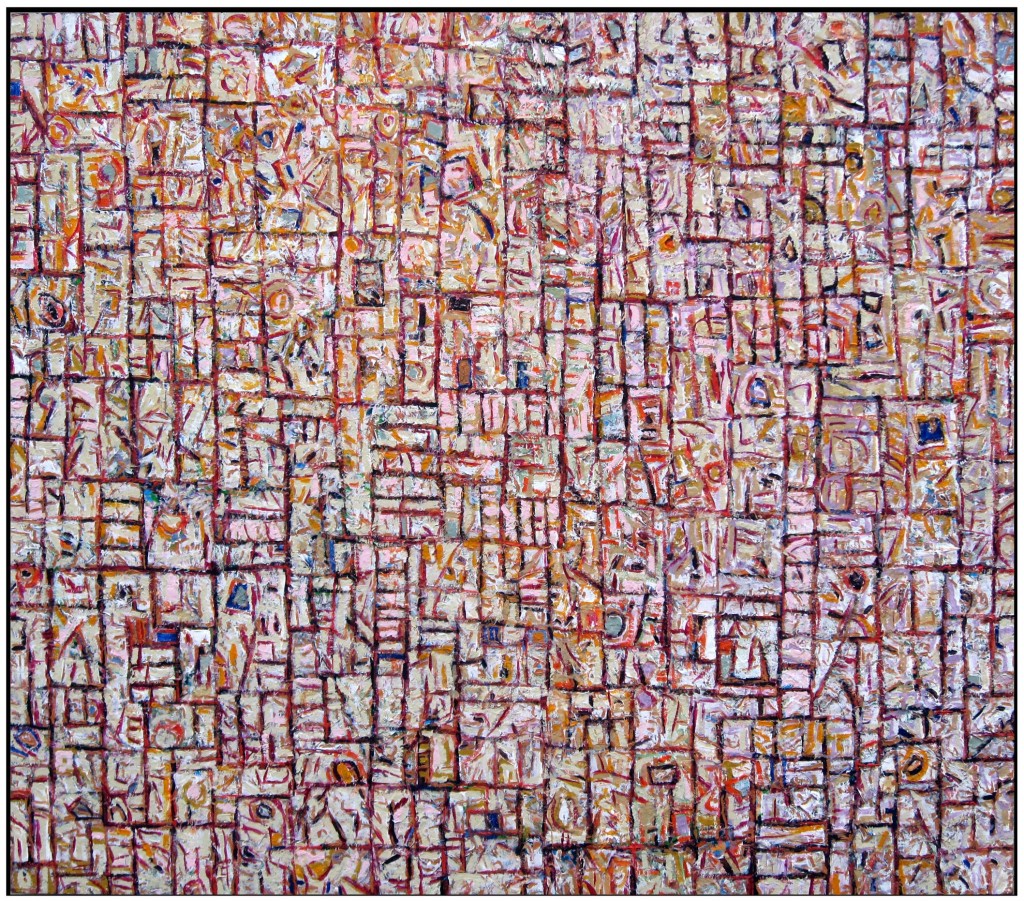

Upon entering Gallerie Camille, the viewer is greeted by “Mitosis”—a large-scale wall-hanging sculpture by Mirek, composed of hundreds upon hundreds of tiny wood scraps. These are the remainders from his labor-intensive series of graphic shape sets, which he designs by computer and then cuts from plywood; two series face off against each other on the walls leading into “Mitosis”: the Strand series on the right, and the newer Thread series on the left. Mirek’s works have a feeling of alien archeology, and the interspersing of his work with that of Schubatis is nearly seamless. The two artists inadvertently echo each others’ palettes, and her abstract and lovely wall-hangings and humorous rock-based sculptures look right at home alongside his meticulous vocabulary of symbols and oil paintings that veritably leap off the page in their desire to achieve the greater dimensionality accomplished by his sculptural forms. “Mitosis,” with its many constituent parts, is the perfect centerpiece for the show, which features work that seeks to impose order upon a chaos of objects, symbols, and materials.

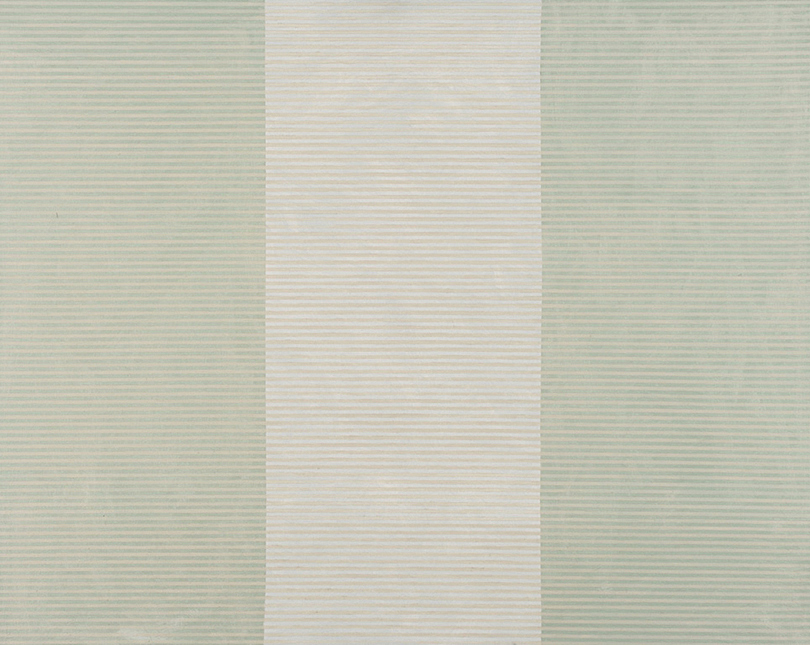

John McLaughlin, Ground Floor (diptych) Painting / Collage

This is evident in McLaughlin’s work, which sits mostly apart from the others, in the deep-set black box gallery. Collage typically implies the layering of images—by contrast, McLaughlin’s mixed media drawings on paper are a colorful motif of stand-alone squiggles, each cut from media materials, which occasionally abut each other, but do not overlap. The effect is something like pouring a colorful jigsaw puzzle out onto a white table; there is a sense of some potential connection or relationship between these shapes, but it is not figurative and not explicit. The whitespace becomes equally as important as the particulates, and the eye caroms around the visual static, looking for imagery—a kind of highly mediated form of cloud-watching. Though his work stands physically and materially apart from Mirek and Schubatis, McLaughlin’s works collectively reinforce the effect created by ECHOES, with swarms of shapes hanging together that effectively echo Mirek’s symbol-clusters in the main gallery.

Schubatis, Wall Hanging, flanked by Mirek’s Paintings

Schubatis has drawn her components into an even tighter matrix—that of the woven body. Her weavings have been, at times, highly experimental in her incorporation of odd materials, such as caution tape and other plastic waste, but even in these more conventional wall-hangings, her impeccable sense of balance and bold color choices make for dynamic and achingly lovely compositions. In the center gallery, which is almost entirely work by Schubatis, these are interspersed with sculptural oddities—improvisations on rock forms, embellished with melted candlewax, paint, and bedazzling gemstones. The combination of bold materials, mineral shapes, and paradoxically minimalist finish create a kind of paleo-futuristic effect; these works would be fitting interior decorations for the Starship Enterprise.

Robert Mirek, Stand Series, detail view

Or perhaps, again, that influence is seeping through from Mirek’s work, which inescapably suggests alien art: mysterious shapes that beg for translation. The Strand series finishes his plywood forms in an exterior of gray pumice punctuated by sharp chartreuse pebbles of window glass. There is an undersea feel to these, like the superstructure of a reef, the rough irregularity of which has given rise to vibrant life. The Thread series reveals more of the underlying woodwork, and give the sense of architectural models for fabulously modern space-buildings and complexes, with the threads tracing out colorful infrastructure—water lines, green spaces, or transit systems (hovercrafts, one imagines). In the small transitional space between main gallery and the back room dominated by Schubatis, her work and Mirek’s mix almost indiscriminately. Here, a wall hanging is flanked by two of Mirek’s standalone wall sculptures, which tonally mimic each other so perfectly that the truth of that happy accident seems stranger than fiction. There, another woven piece by Schubatis provides a calm striation of undulant yellow-on-gold-on-brown forms, which make a harmonious landscape for several pieces from Mirek’s Scorch, series, which seem almost carved out of bone, with the darker backdrop material revealed, upon closer inspection, to be hundreds of tiny drawn and glued elements—replicating just like cells, alluded to in the title of Mirek’s sprawling centerpiece.

Altogether, much to be considered and enjoyed within ECHOES, proving that sometimes the best part of work is the visual echoes that emerge when visions bounce off each other.