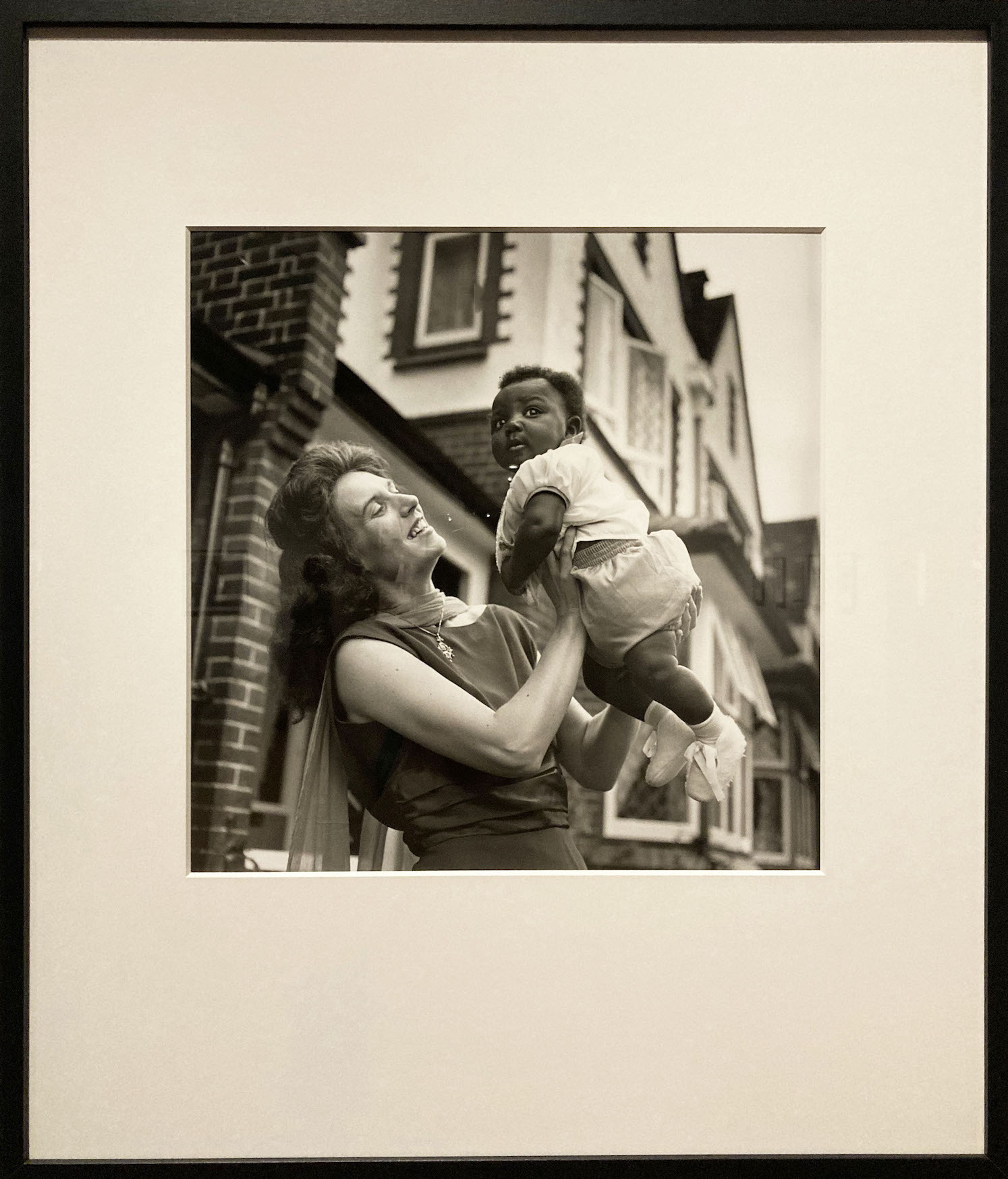

Shouldn’t You Be Working? 100 Years of Working from Home installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2023. Photo: Vincent Morse/MSU Broad Art Museum.

In 1896, Michigan State University opened the doors to its School of Home Economics, one of the first in the nation. The school even contained a fully functional practice home where the students cooked, cleaned, and hosted events. The home was demolished in 2008, and the Broad Art Museum was erected in its place. Taking its former school of home economics as its reference point, through December 27, the Broad presents Shouldn’t You Be Working? 100 Years of Working From Home. Curated by Teresa Fankhänel, the exhibit features photography, digital media, and installation, and it explores the intersection of work and home life, focusing on how technology and artificial intelligence are shaping the future of both.

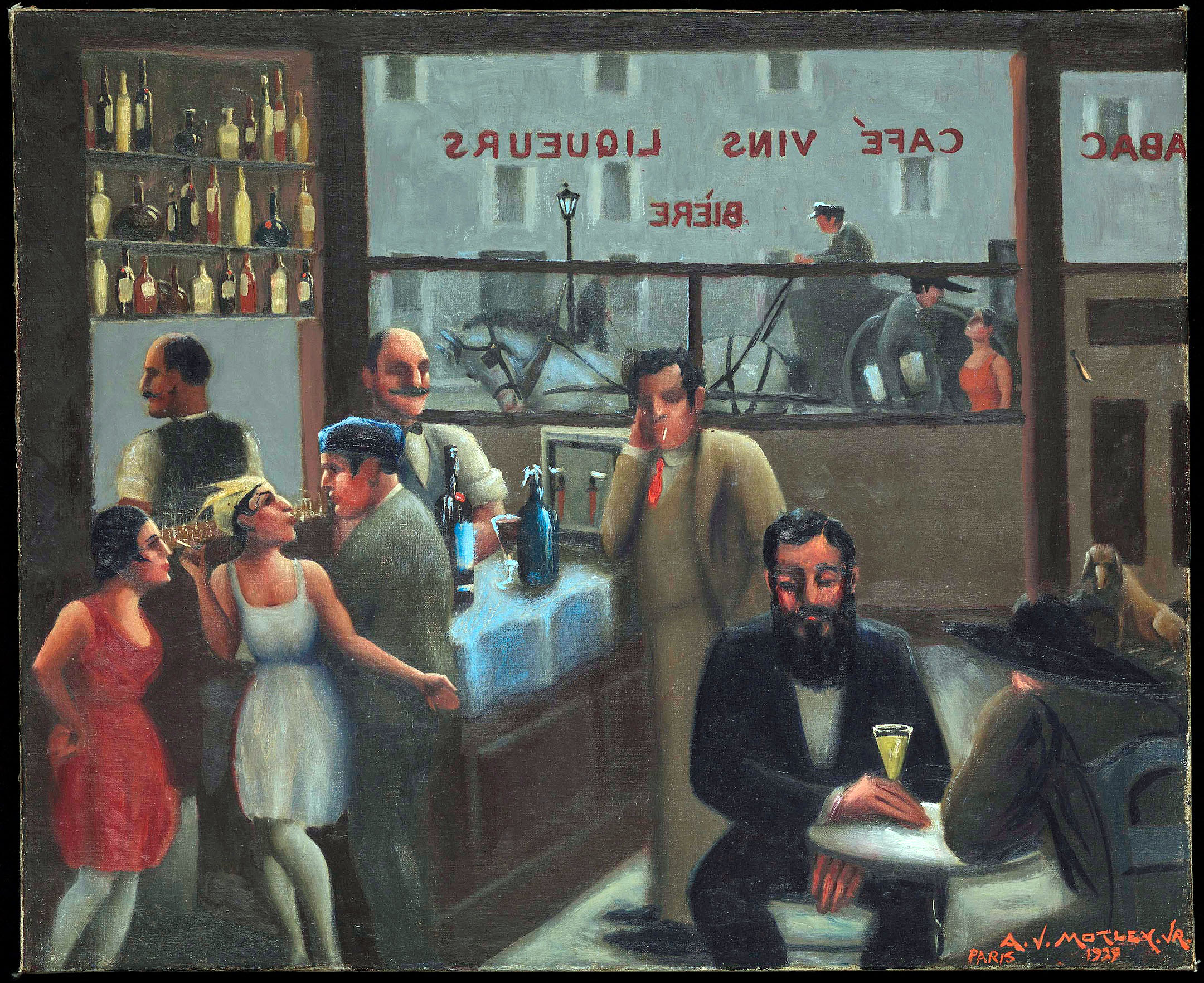

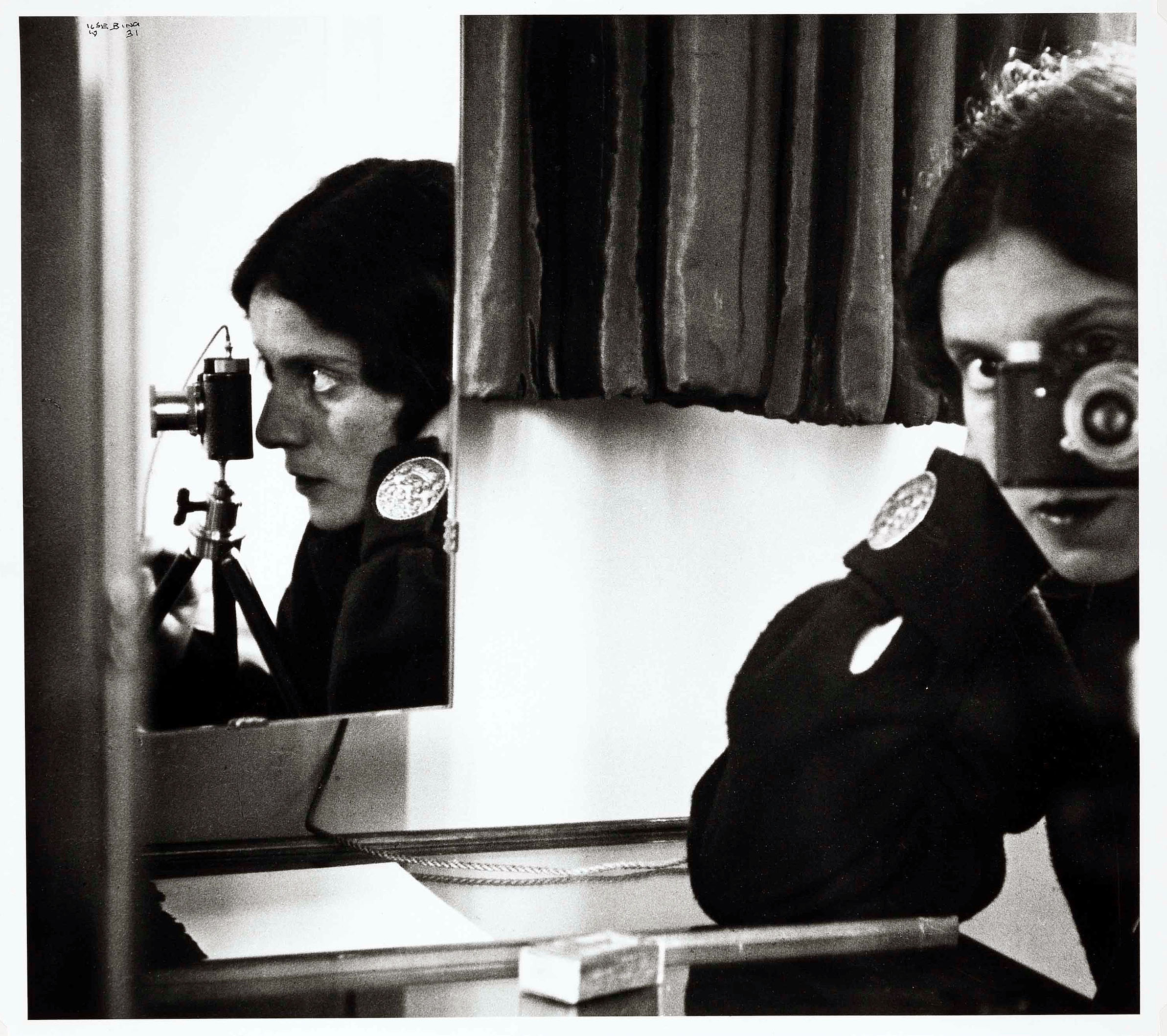

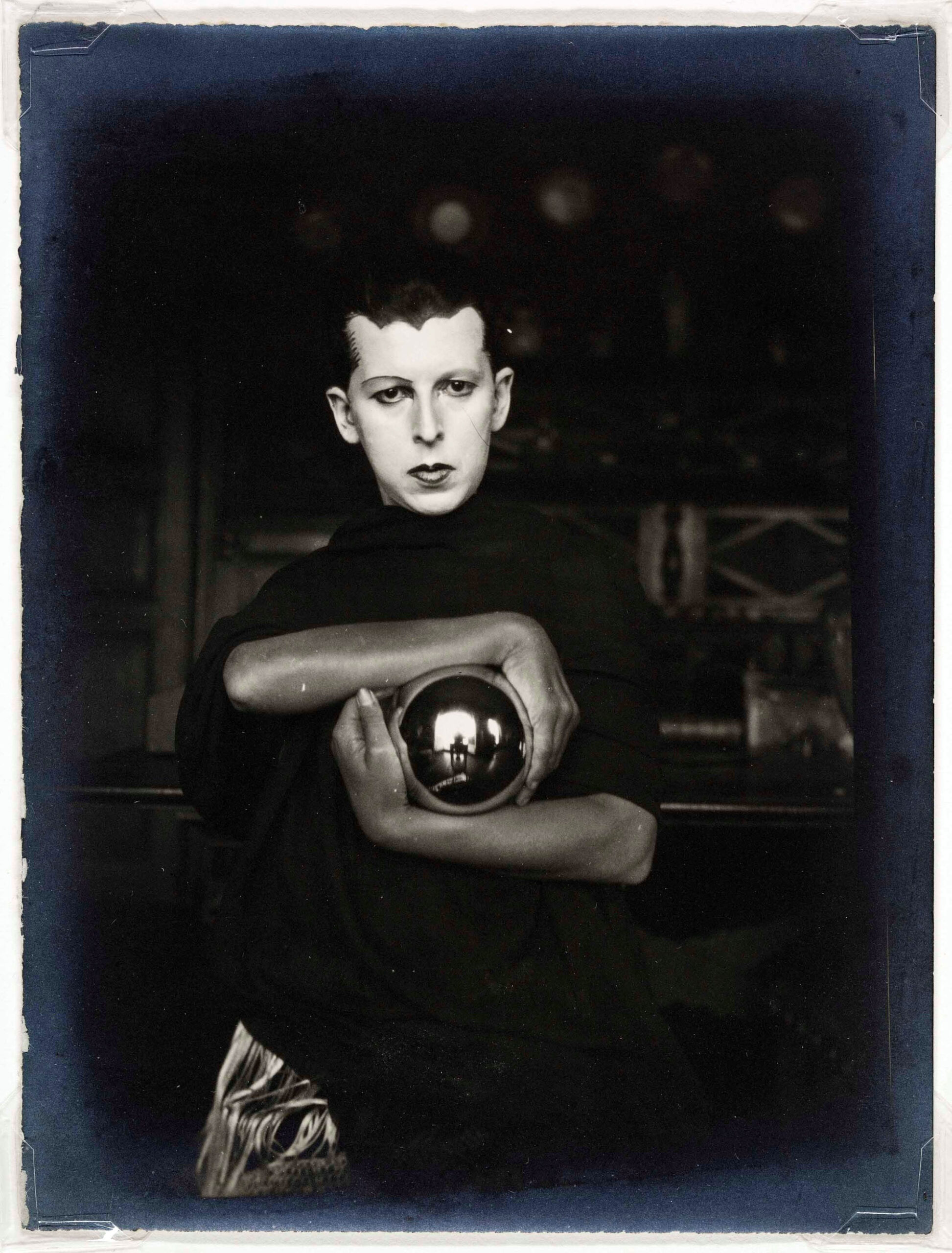

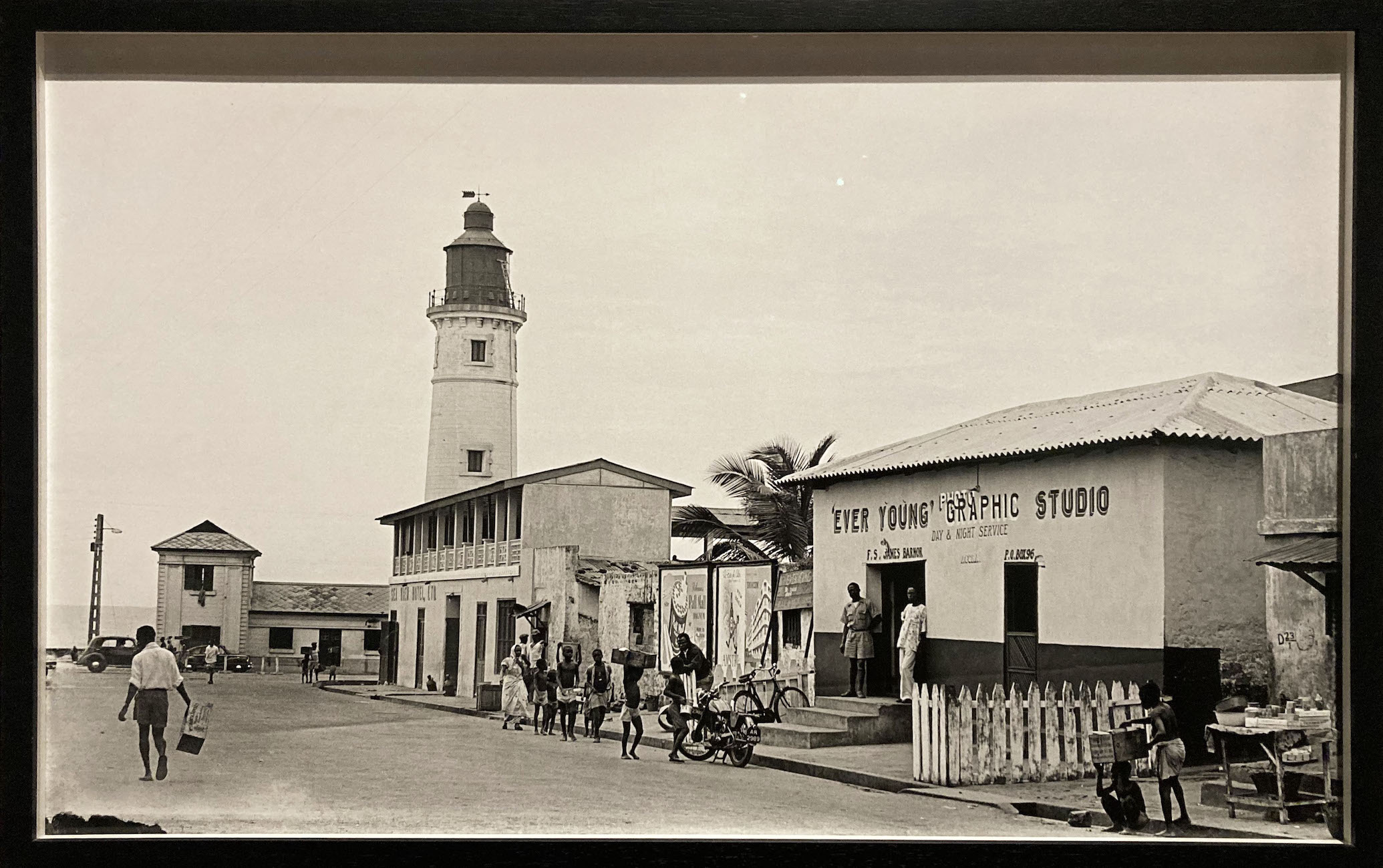

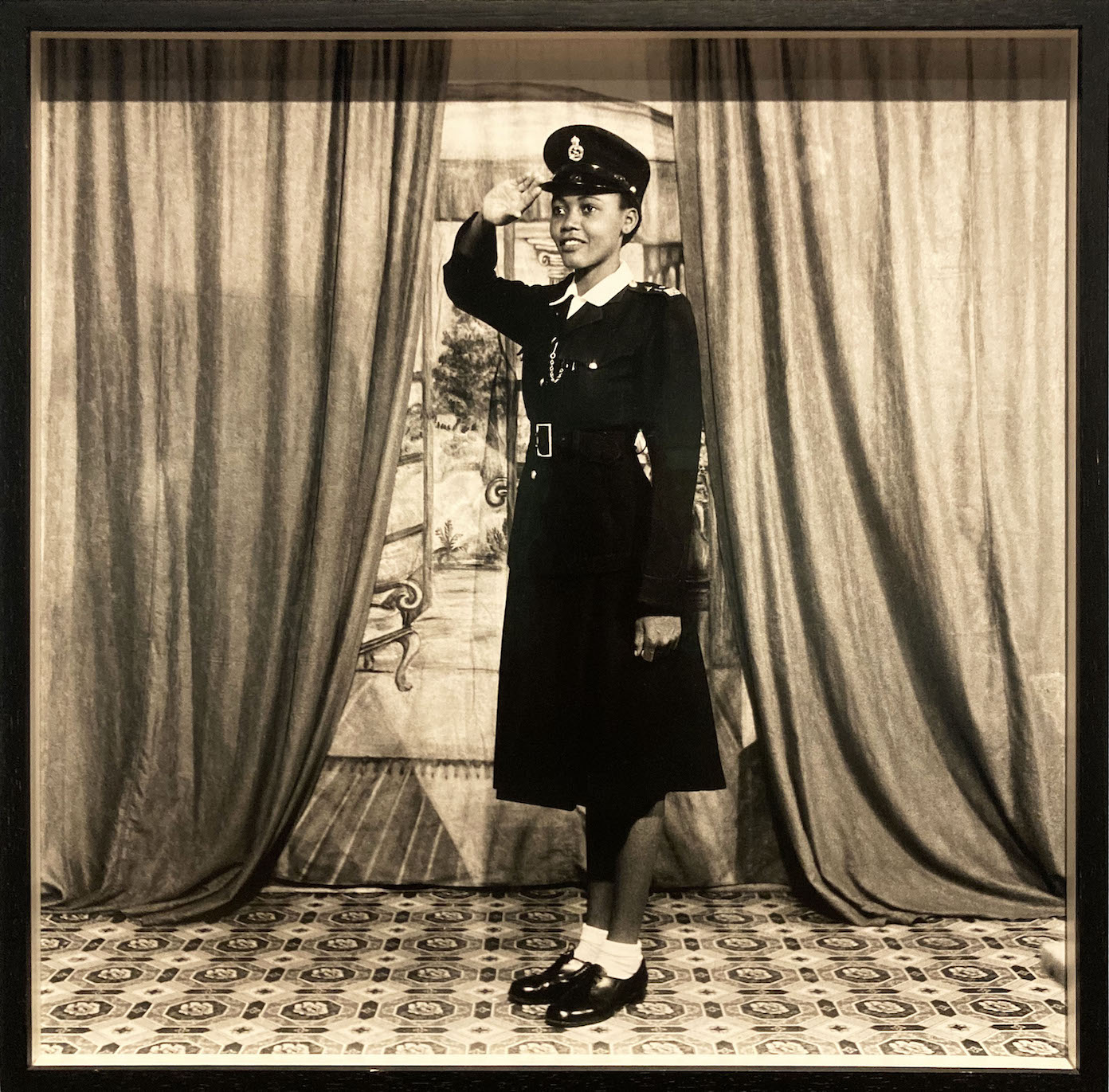

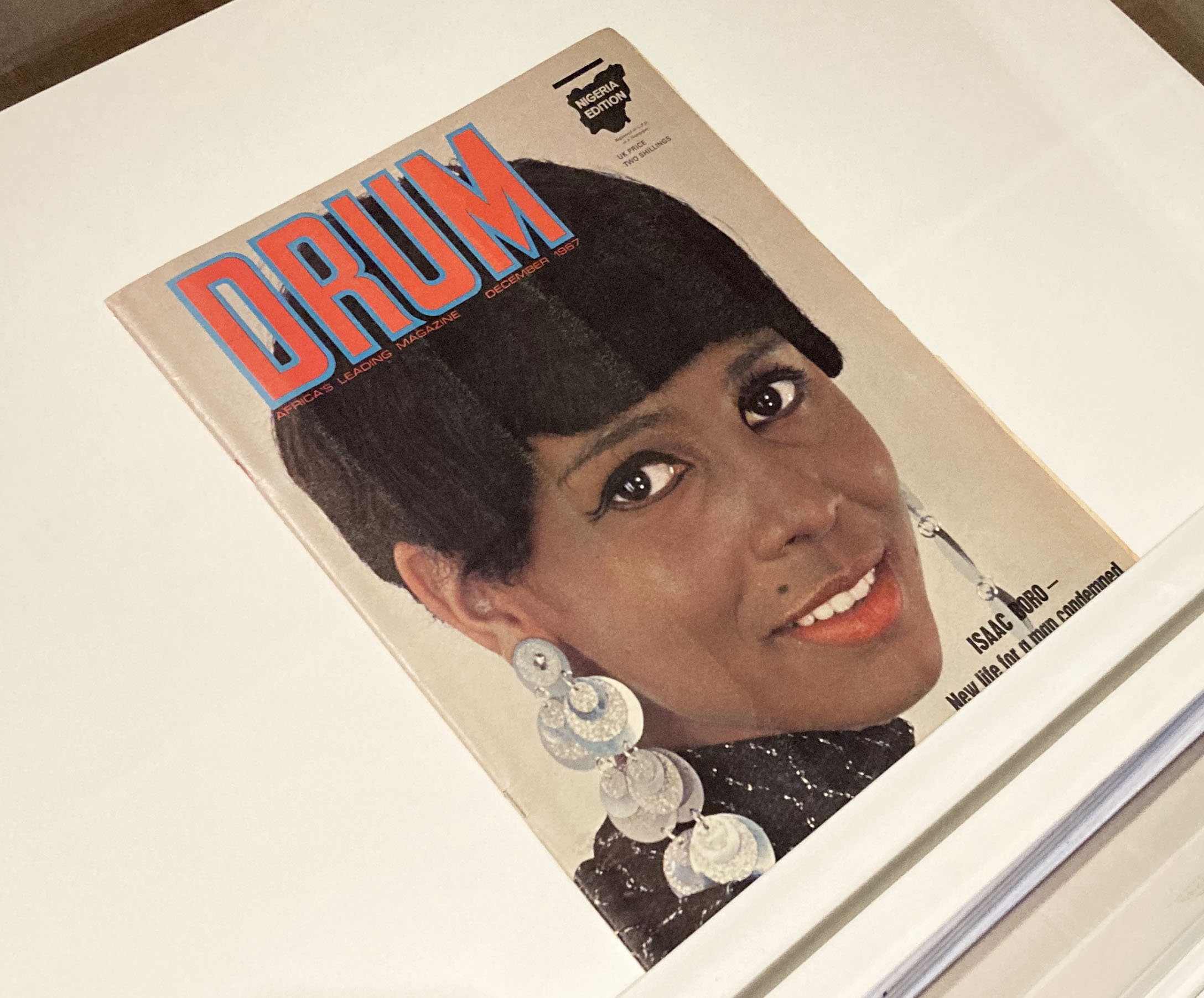

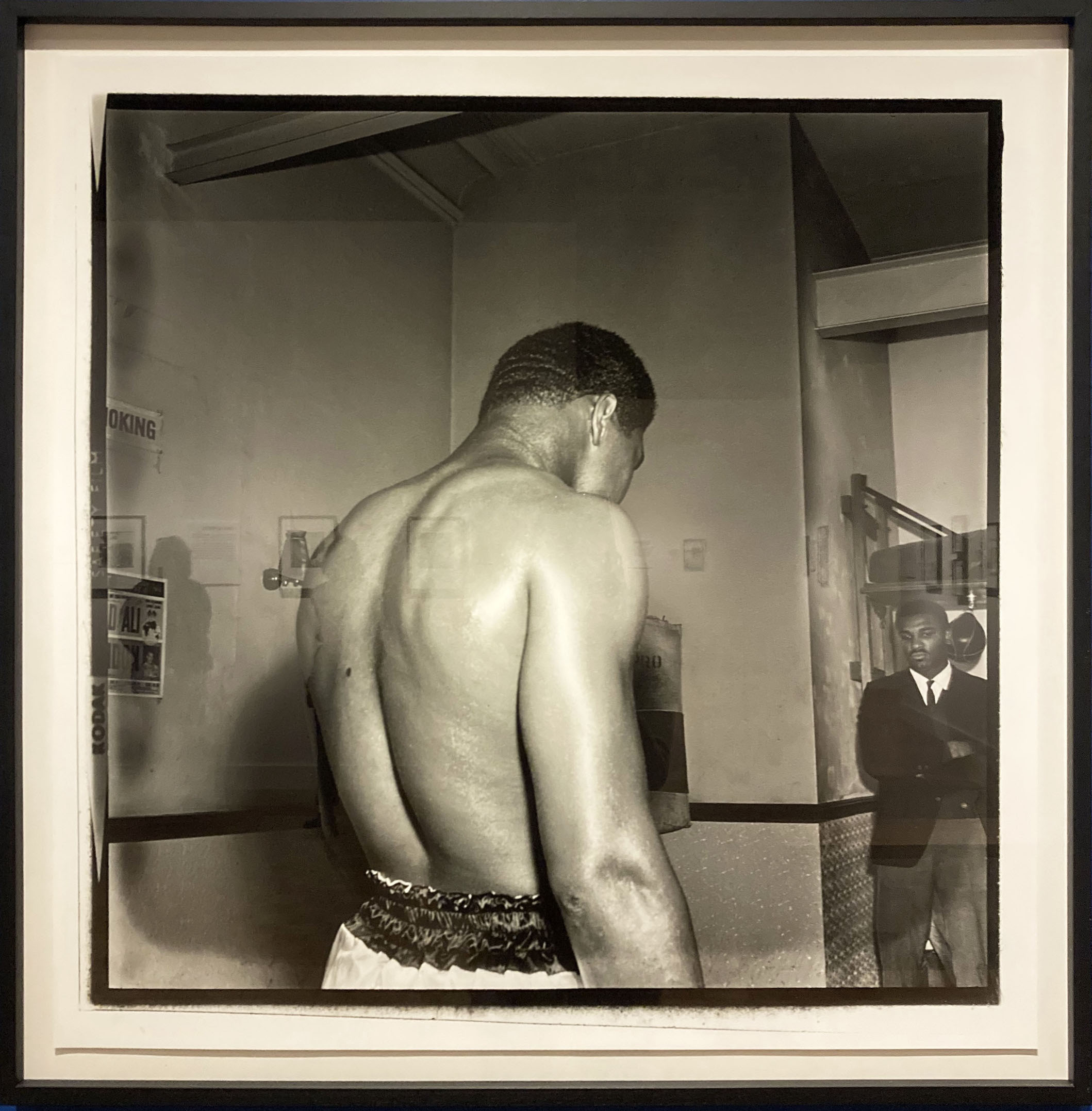

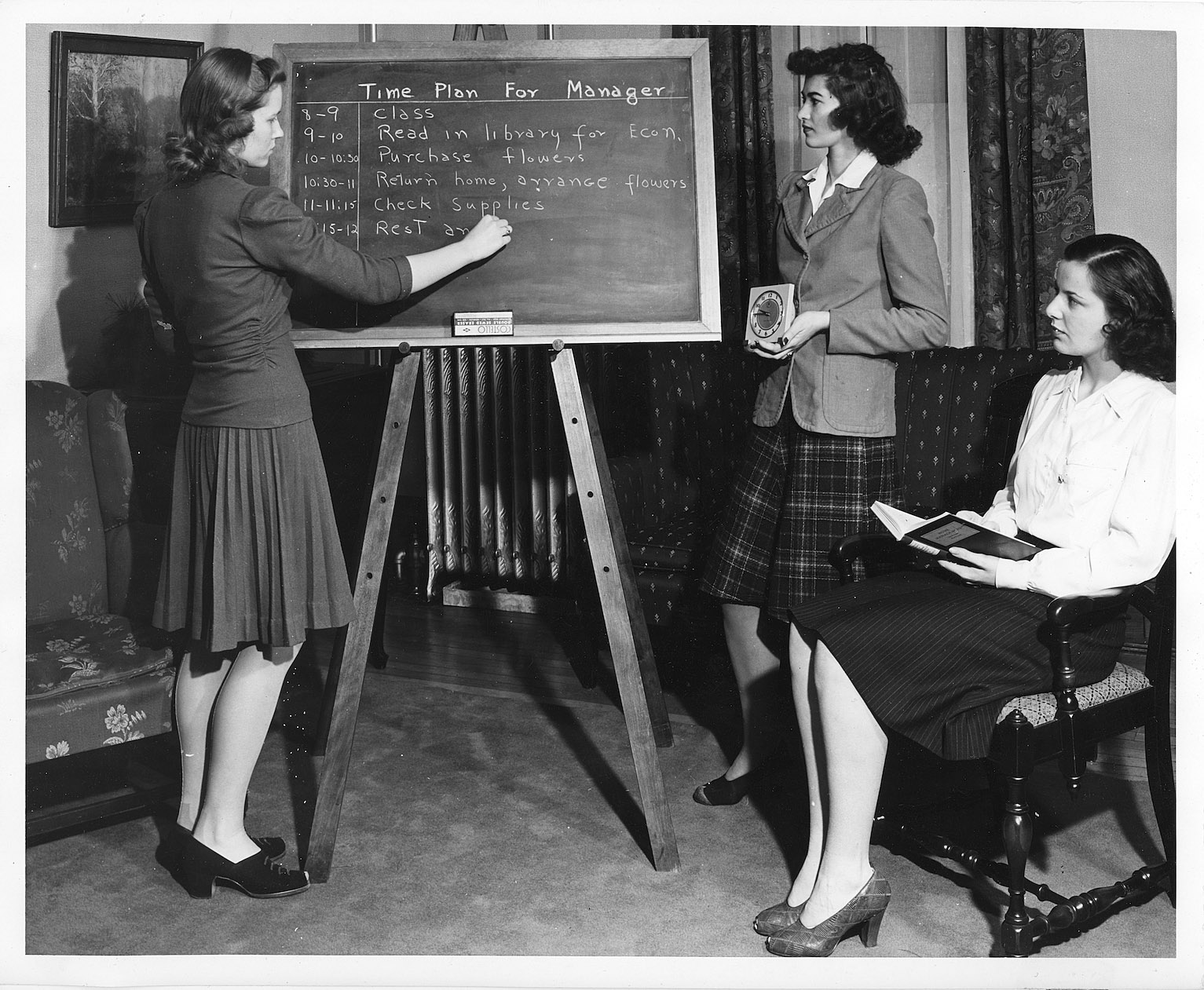

This exhibition pairs ten contemporary artists and architects with a selection of photography and ephemera, including archival photographs from the university’s former School of Home Economics. These are paired alongside iconic photographs of workers in their homes, taken by the likes of Walker Evans and Marion Post Wolcott, who, on behalf of the Farm Security Administration, famously documented the lives of the rural workers and sharecroppers who struggled to maintain their livelihoods during the Great Depression.

Records of the MSU School of Home Economics. Courtesy Michigan State University Archives & Historical Collections.

Marion Post Wolcott, A member of the Fred Wilkins family making biscuits for dinner on cornhusking day, Tallyho, near Stem, N.C., 1939. Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, Michigan State University, purchase, funded by the Emma Grace Holmes Endowment, 2006.33.1

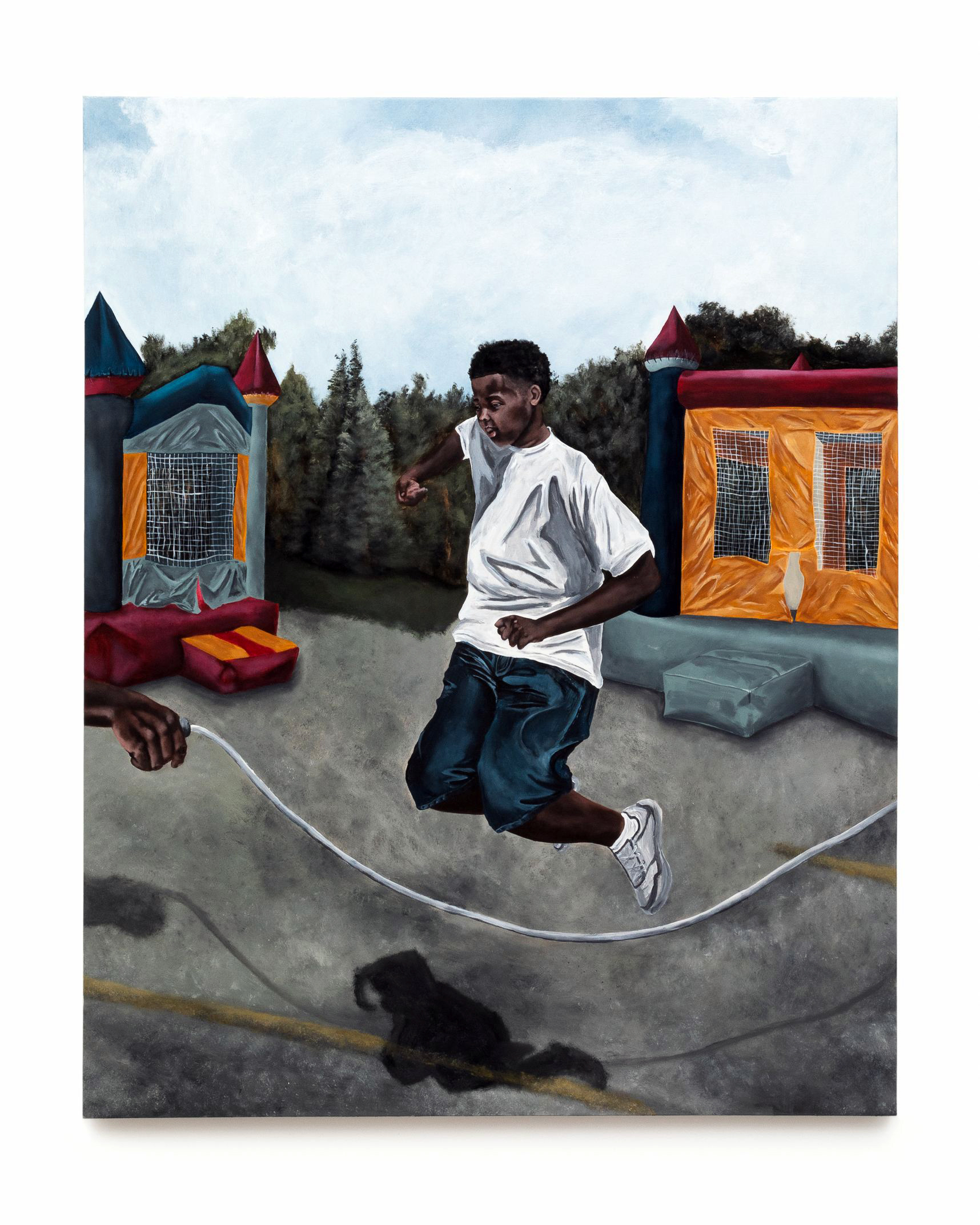

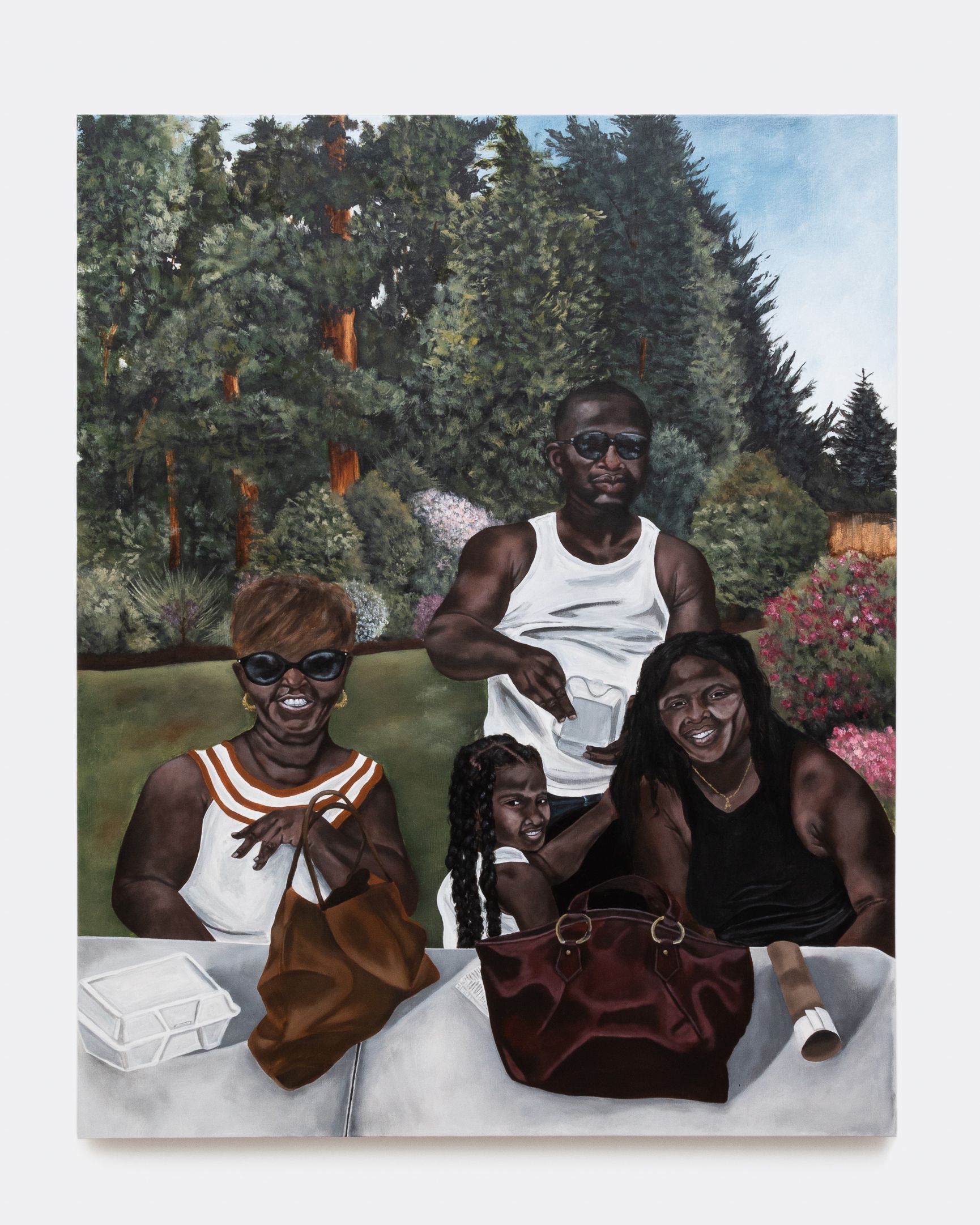

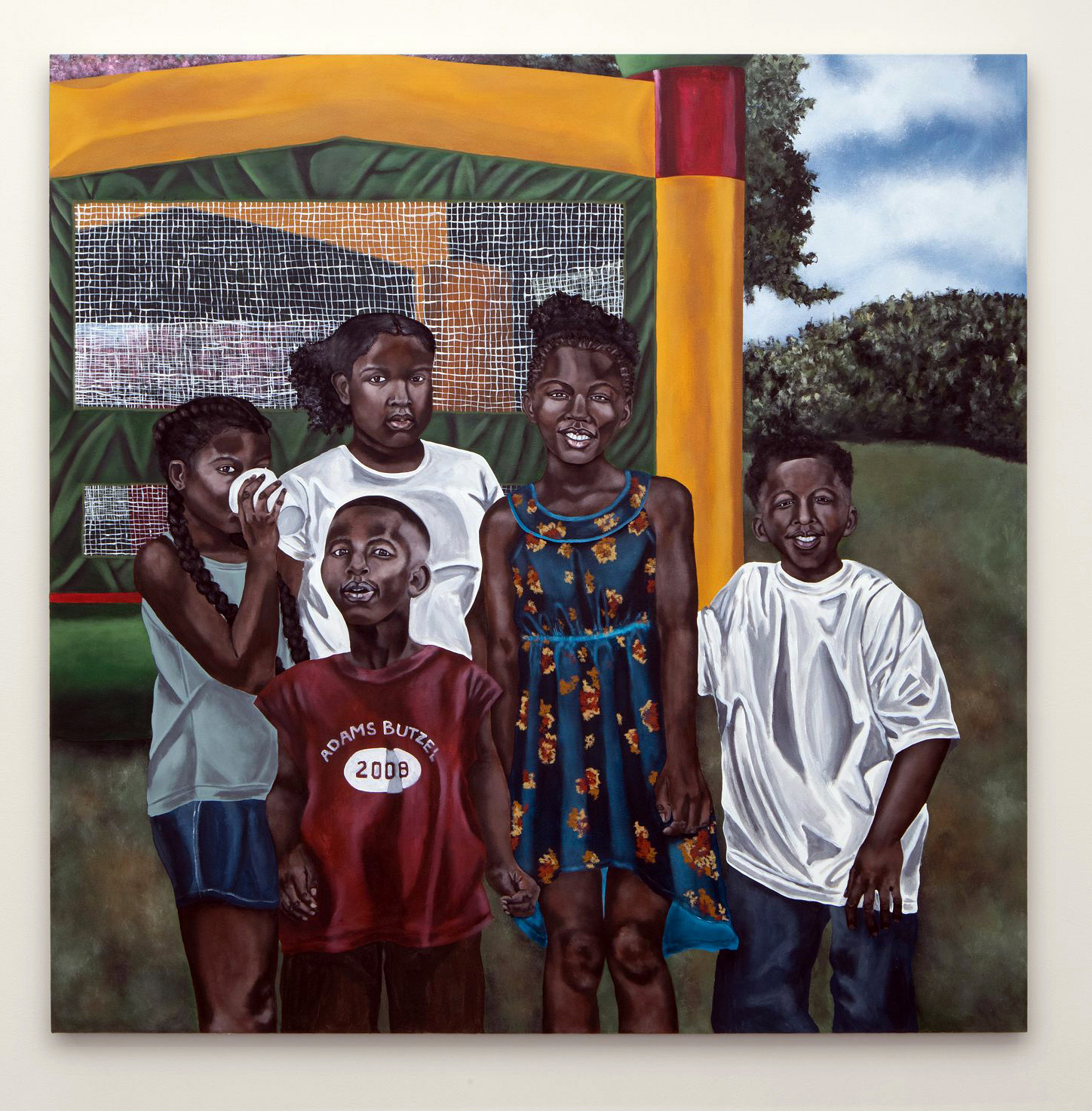

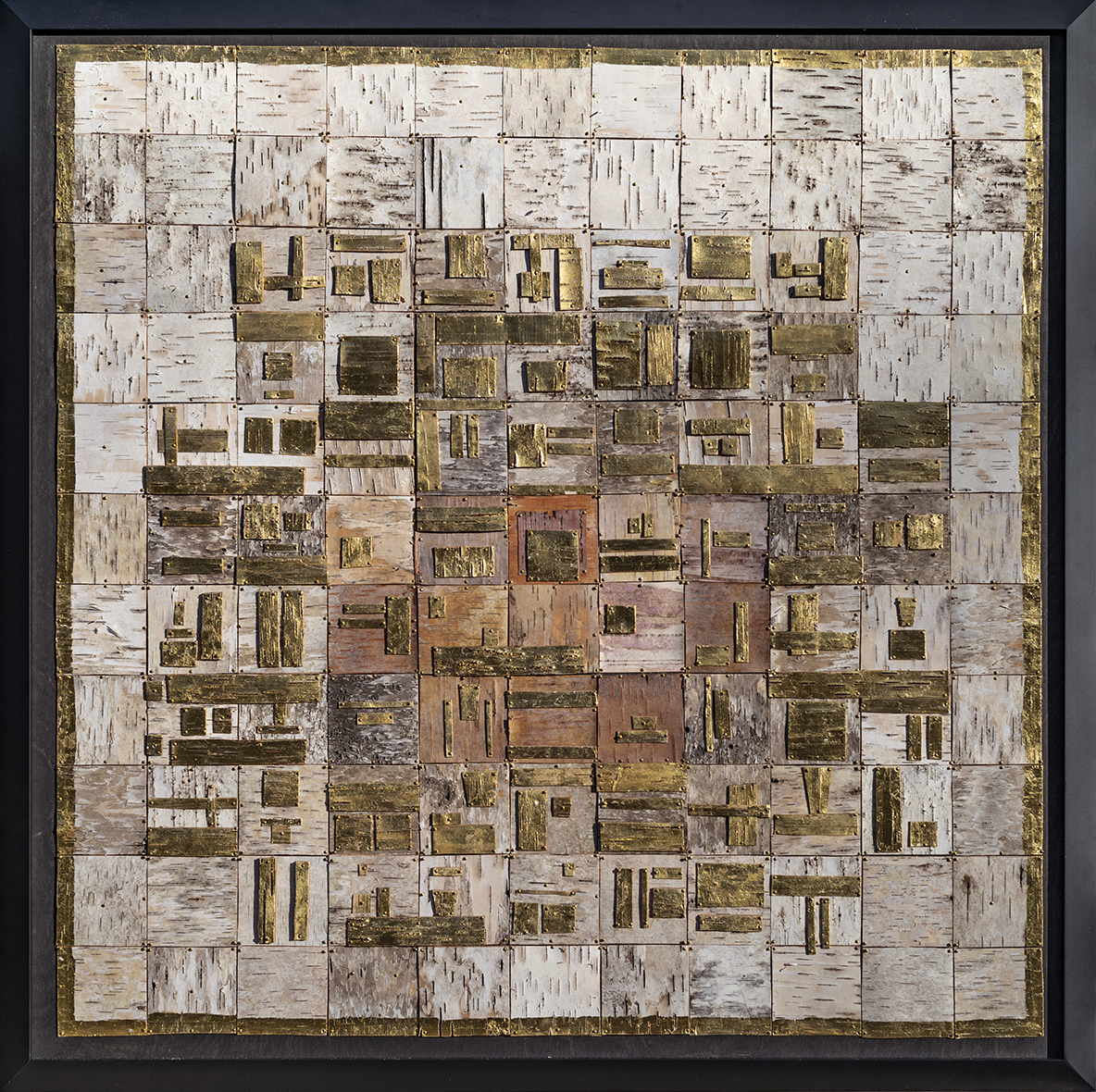

The visual epicenter of the exhibition space is a partial recreation (at a 1 to 1 ratio) of the Paolucci Building, the former home economics practice house that once occupied this site. This interactive structure serves to frame a selection of photography, digital art, and an installation, which explore contemporary intersections of work and home life. Inside, there’s a mock-up of a home office replete with all the trappings of a television studio; a sight which will resonate with any of us who have been on a Zoom call. It also recalls the home studios of the social media “influencers” who ironically manage to create lucrative public careers from the privacy of their homes. This office installation, Cream Screen, by Marisa Olson, also serves to confront and dismantle the assumption that the technology to work or study remotely is accessible to everyone.

Shouldn’t You Be Working? 100 Years of Working from Home installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2023. Photo: Vincent Morse/MSU Broad Art Museum.

Shouldn’t You Be Working? 100 Years of Working from Home installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2023. Photo: Vincent Morse/MSU Broad Art Museum.

Also inside this recreation of the Paolucci Building is a selection of photography by Korean artist Won Kim. His series Living Small shows the cramped living quarters of Tokyo’s pod hotels. Unlike the city’s chic capsule hotels (more refined, but still not for the claustrophobic), these pods are little more than plywood boxes; there’s not even a door or windows. These spaces offer very low-income housing for individuals in between jobs, and are the ultimate expression of minimalist living. These images call to mind the famous photograph Five Cents a Spot taken by Jacob Riis, which shows the crammed tenement housing of some of New York City’s poorest residents.

Won Kim, Enclosed: Living Small, 2014. Photo print © Won Kim

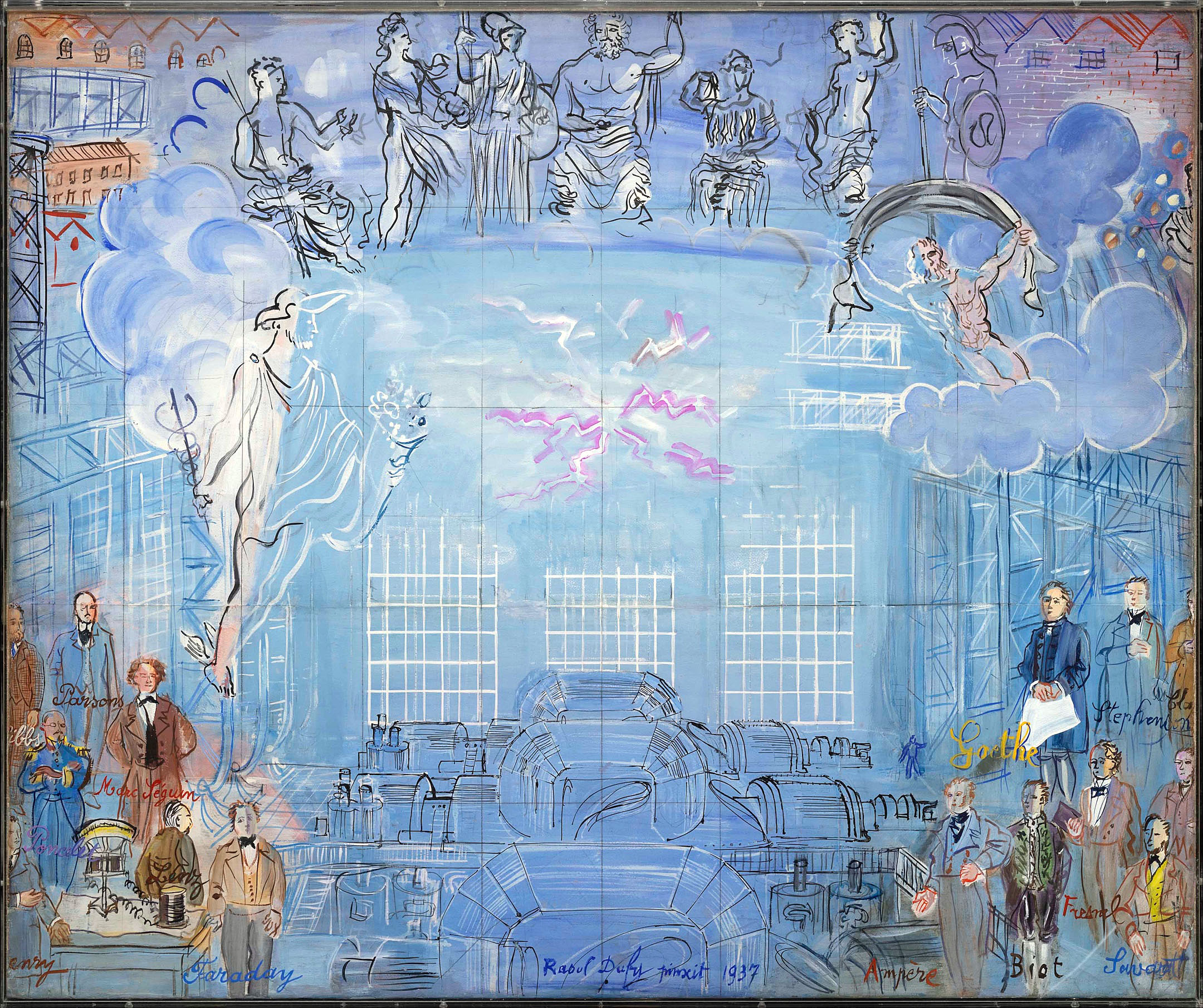

Several monitors screen short video works that specifically address how technology shapes our work/home balance. Theo Triantafyllidis’ Ork Haus applies a sort of dark, absurdist humor in his digital portrayal of a dysfunctional family of orks (yes, orks) at home during lockdown. All are hopelessly addicted to their screens (VR headsets, TVs, and phones). The papa ork dabbles in cryptocurrency, and his little orkling learns to code; meanwhile, the family is oblivious to real-world catastrophes that surround them, such as the out-of-control fire in their kitchen.

Theo Triantafyllidis, Ork House, 2022. Live simulation video © Theo Triantafyllidis

Merger, a video by Keiichi Matsuda, presents us with a dystopian future in which artificial intelligence has taken over all corporations. The film’s unnamed protagonist has resigned to this digital takeover, acknowledging her status as a human is obsolete, and ultimately makes the decision to transition into a digital entity.

Keiichi Matsuda, Merger, 2018. Video © Keiichi Matsuda

For better or for worse, the boundaries between work and home are shifting. And COVID certainly accelerated the process, turning our homes into workspaces, at least for those of us who were fortunate to have the means to work remotely. This exhibition doesn’t necessarily criticize the advent of new technologies in the home, though it does invite us to pause for a moment and consider what this brave new world will look like.

Shouldn’t You Be Working? is on view at the MSU Broad Art Museum through December 17, 2023.