The exhibition space at Image Works is small but highly visible – the display windows on Michigan Avenue, which stay lit all night long.

It may be one of the smallest gallery spaces in the Detroit area. It’s virtually a pop-up. But the art by Karinna Sanchez Klocko hanging in the display windows at Image Works, a fine-art photo-printing shop in Dearborn, is both punchy and well worth a look. With “Memories,” the artist – a young graphic designer living in Commerce – takes a nostalgic look back at her childhood in Monterrey, Mexico, creating digital vignettes that, in the words of the artist’s statement, “capture the memories and dreams of the moment.” “Memories” will be up through May 27.

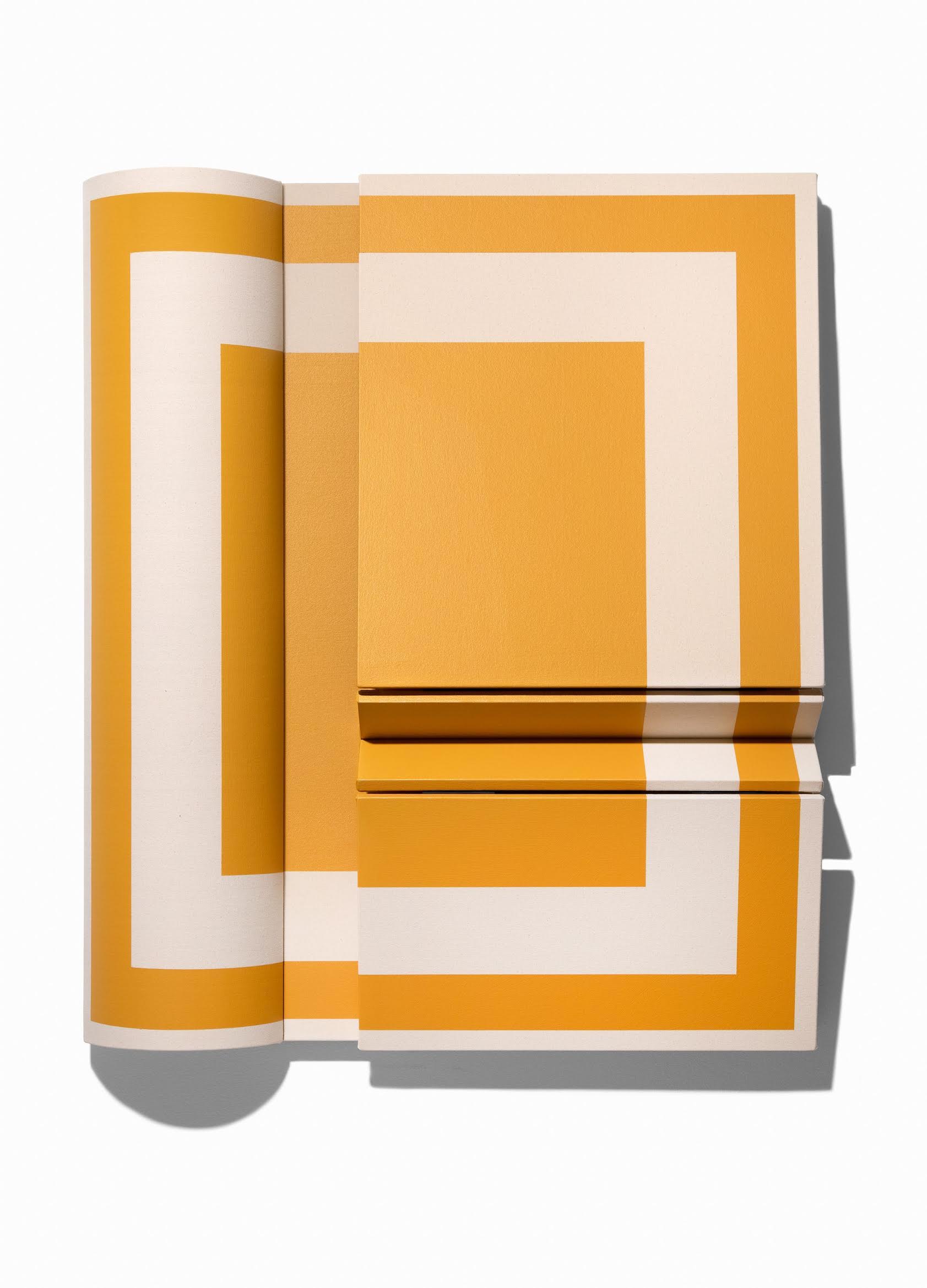

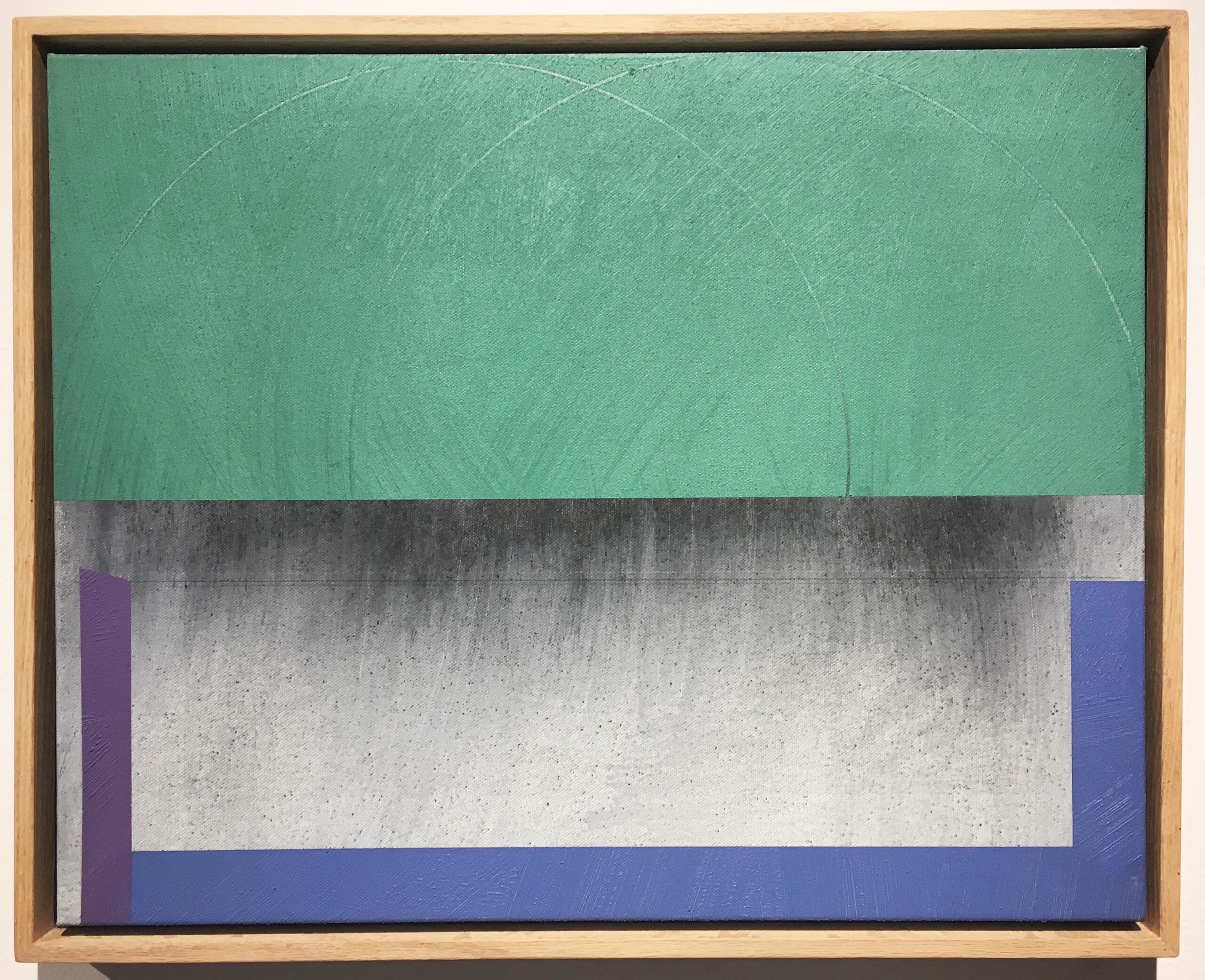

Karinna Sanches Klocko creates her vividly colored, untitled canvases on the computer.

What you find at Image Works is a handful of sunny, color-drenched interiors, all accented with sprays of tropical flowers. The mood is cheerfully nostalgic, not syrupy. The domestic subjects – among others, a hallway leading to a front door, a bureau partly covered by a floral tablecloth, and a kitchen corner with fruit hanging in baskets next to an old “Trimline” wall phone – are unremarkable in themselves, but radiate light and comfort and “home.” The point of view is highly personal, as if the artist were, indeed, trying to reassemble scenes once commonplace, but now far in the past and scattered.

The artist’s digital creations take an affectionate look back at her Mexican childhood.

There’s a specificity to the images that’s engaging. The kitchen counter is guarded by a tiny, metal turtle. Flower pots on the bureau have highly particular designs that feel rooted in reality. So too with the blue, patterned-tile floor leading to the front door. These are digitally created designs, of course, not photographs. But there’s a distinct Kodachrome quality to Klocko’s color palette – a radiant spectrum that if not unique to Latin America, certainly typifies much of the art that’s blossomed in warmer and sunnier lands south of the Rio Grande.

Image Works owner Chris Bennett, who moved to Detroit from Portland, Oregon, five years ago, says he first got to know Klocko when she came in as a customer. A lot of artists, he says, bring work to him for digital reproduction. In Klocko’s case, Bennett liked what he saw, and invited the Michigan State graduate to do a show.

It may seem counterintuitive, but maintaining a gallery in a photo shop has long been Bennett’s habit and ambition. “I love exhibiting artists’ work,” he said, “and it’s a great way to build community as well. It adds another element.”

Bennett moved to the present Michigan Avenue location last July from his old shop in Dearborn. While he doesn’t have as much gallery space here as before, he’s got dynamite display windows fronting a major thoroughfare that seem design-made for his intentions: “I wanted to do large-scale pieces that could easily be seen from the road,” he said, “that would attract people’s attention without causing accidents.”

In another civic-minded gesture, Bennett leaves the window lights on all night long – offering a bright dash of color that’s bound to surprise west-bound drivers in the wee hours.

Albert Kahn: Innovation & Influence @ Detroit Historical Museum

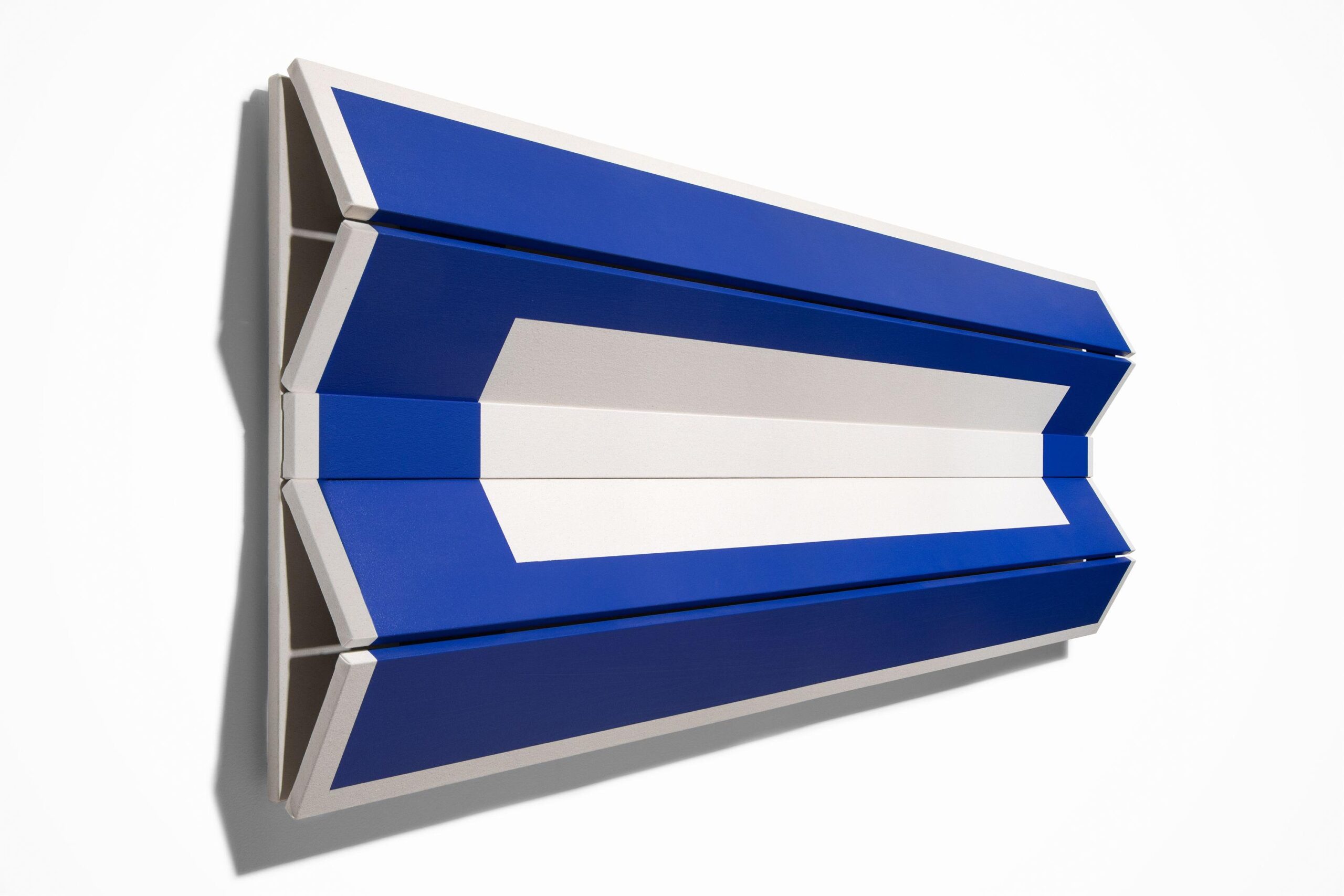

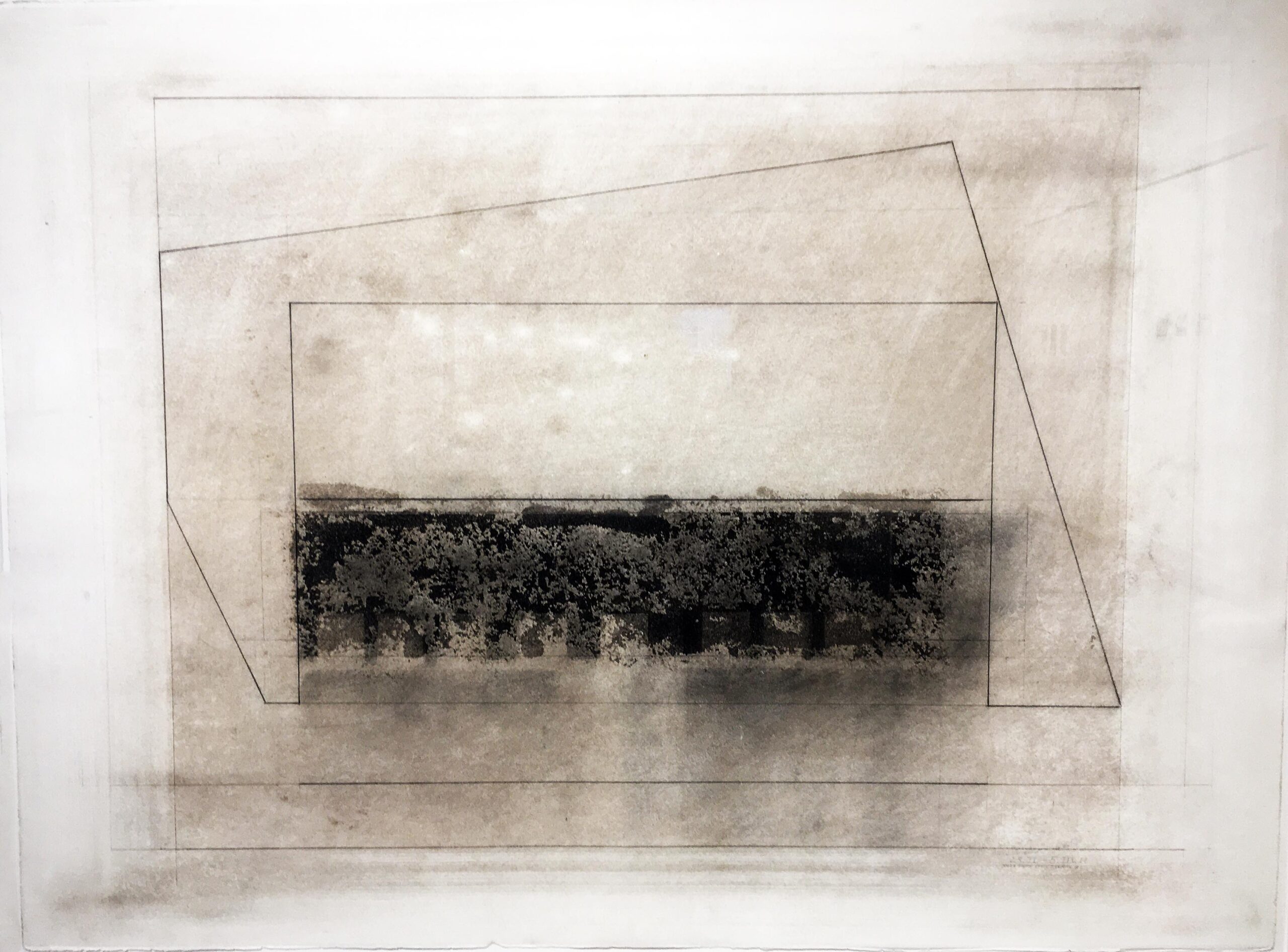

An installation shot of the Albert Kahn exhibition at the Detroit Historical Museum. (Michael G. Smith)

An outstanding new exhibition on Detroit’s most-famous architect, “Albert Kahn: Innovation & Influence on 20thCentury Architecture,” is up at the Detroit Historical Museum through July 3. Organized by the new nonprofit Albert Kahn Legacy Foundation, with a mission to “honor, educate and preserve,” the show aims to broaden knowledge and capitalize on the recent uptick in the industrial architect’s reputation nationwide.

This is a handsome exhibition with a number of salient virtues — not too big, not too small, enlivened by smart, concise text, cool graphic design, and striking Lego replicas of some of the architect’s most famous buildings.

What’s not to like?

Start with the Lego structures. The eight-foot-tall model of the Fisher Building at the center of the gallery is a total scene-stealer. Made up of 120,000 pieces, the 300-pound behemoth is the work of local Lego-master James Garrett, who specializes in models of Detroit’s pre-war architecture. Other replicas on display include the Russell Industrial Center (originally the Murray Body Corporation) and Capitol Park’s Griswold Building, long empty but now renovated into luxury apartments and rechristened “The Albert” in honor of its designer.

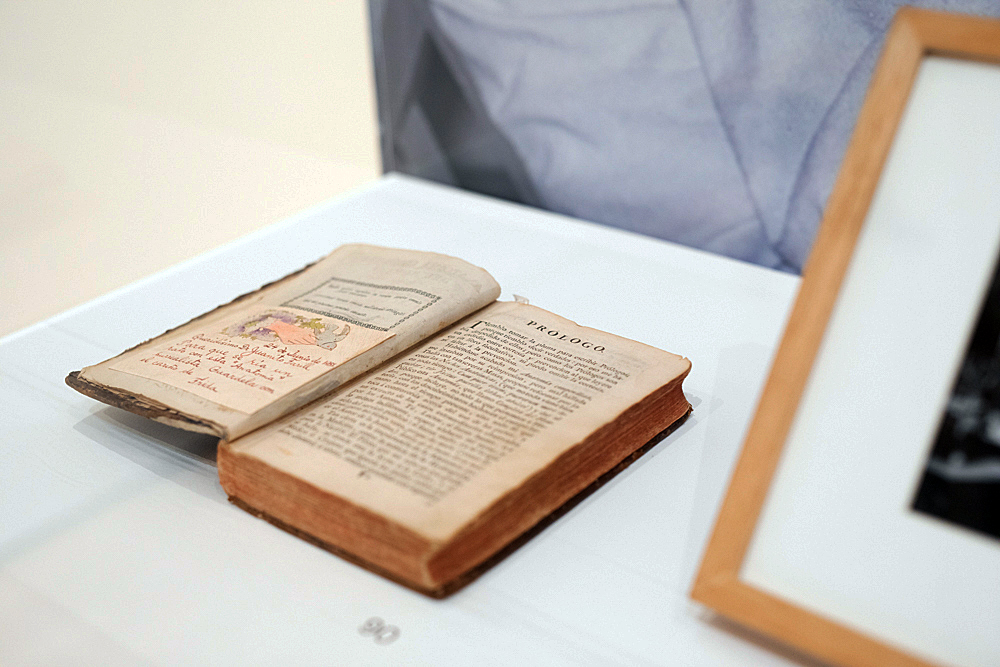

The show does a superb job laying out Kahn’s early life, and his arrival in Detroit as an impoverished Jewish immigrant when he was about 12. From there on, of course – once he lands his apprenticeship with Mason & Rice, a highly significant downtown firm – the youngster scaled the professional ladder quickly and with astonishing ease. Among other things, Kahn from an early age was a remarkably gifted freehand sketch artist (credit his teacher – Detroit artist Julius Melchers), and the show contains several of his drawings from European travels.

Albert Kahn, seated at left, in the offices of Mason & Rice when he was about 19. (Albert Kahn Associates)

For those who don’t know Kahn’s work well, there are also some marvelous surprises here — not least the fact that the Fisher Building, as we know it, is only one-third of a massive complex with a central tower that got scotched once the stock market crashed in 1929.

The exhibition also lays out the Kahn firm’s astonishing work in the late 1920s and early 30s building over 500 plants and factories across the Soviet Union, an effort that industrialized what had been a backward, agrarian economy. Want to know why the USSR didn’t collapse when the Nazis invaded in 1941-42? The answer has a lot to do with the armaments that rolled off the production lines of Kahn-built factories like the vast Stalingrad Tractor Plant.

The exhibition also explores the architect’s relationship with Henry Ford, Kahn’s most-important client from 1908 on, when he began to design the Highland Park Model-T plant. It also discusses his relationship with the automaker once the latter’s Dearborn Independent newspaper launched a weekly series of anti-Semitic screeds in 1920, “The International Jew: The World’s Problem.” (Despite this, Ford clearly liked and admired Kahn, calling him “one of the best men I ever knew” on the architect’s death in 1942.)

Kahn’s revolutionary, reinforced concrete factories for Ford, with their lack of ornamentation, huge windows, and geometric-grid facades, established the standard for modern industry worldwide in the early 20th century. They also, as the section titled “Kahn’s Influence on Modernism” details, had a seismic impact on young architectural rebels in Europe desperate for a new, “pure” architecture, which they found in Kahn’s stripped-down Ford plants. Both Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier cited the Highland Park complex in writings that laid out the tenets of early architectural modernism.

All in all, this is a show anyone proud of Detroit’s architectural heritage will not want to miss. Indeed, Albert himself would be proud.

One of Kahn’s crowning achievements – the Fisher Building arcade and lobby. (Michael G. Smith)

Karinna Sanchez Klocko: “Memories” at Image Works in Dearborn will be up through May 27.

Albert Kahn: Innovation & Influence on 20th Century Architecture will be at the Detroit Historical Museum until July 3.