Kwame Brathwaite, Installation image courtesy of DAR

On October 8, the Detroit Institute of Arts opened its doors to Black is Beautiful: The Photography of Kwame Brathwaite. The exhibit features over forty black-and-white and color photographs from the New York-born photographer known for his activism just as much as his eye behind the camera.

The first thing you have to do is understand the premise in which, “Black is Beautiful ” was created. The civil rights movement; a collective endeavor by black Americans to eliminate racial discrimination had started in the late 1940s. Black Americans wanted equal entry in the same economical, educational, housing spaces as their white counterparts. Remember, we’re talking about a time period in which black Americans didn’t even use the same water fountains and bathrooms. But by the early 1960s, there was an energy shift within Black America. There was a new aggressiveness and intentionality bubbling outside the scope of the Civil Rights movement. There were activists that felt the quest for integration was sacrificing self-acceptance.

This is where Kwame Brathwaite enters the picture. On a cold Harlem night in 1962, he hosted a fashion show featuring audacious models with afros and natural hairstyles. They were a visual protest to western beauty standards. The women (known as the Grandassa Models) would go on to be Brathwaite’s muse and kick start the “Black is Beautiful” movement. The movement ran simultaneously with the “Black Power” movement and opened the door for self-awareness, self-empowerment, and pinched some of the insecurities among black people.

Kwame Brathwaite, Photoshoot at a public school for one of the AJASS-associated modeling groups that emulated the Grandassa Models and began to embrace natural hairstyles. Harlem, ca. 1966; from Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful (Aperture, 2019)

“I really felt it was important to bring in a photographer that could speak to the black experience. ……What this exhibition really stresses is the work he did with the Grandassa Models. You can see large-scale photographs that were involved in the fashion shows that he organized in the 1960s, one actually came to Detroit in 1963,” says Nancy Barr, Curator of Photography for the DIA.

Upon entering the gallery a selection of large 5×5 portraits draws first draws the viewer’s attention. The brown-hued complexion on the portrait of model Ethel Parks is rich in energy. Her expression is a bit cunning and her presence feels life-like as her eyes seem to look back at you no matter what angle you’re viewing her portrait. The background is red, her hair is covered, and there is a sharp light fall-off at the edge of Park’s face which punctuates the energy in her appearance. This is the most dramatic lighting Brathwaite uses in this series of portraits.

Kwame Brathwaite, Model Ethel Parks at AJASS Studios, ca. 1965

Kwame Brathwaite, Sikolo Brathwaite, African Jazz-Art Society & Studios (AJASS), Harlem, ca. 1968

The two portraits of model Sikolo Brathwaite are subtle but confident. She wears a headpiece designed by artist Carolee Prince in front of a bronze background and a full picked-out afro in the other. The two portraits truly epitomize Brathwaite’s message and his definition of beauty. Sikolo Brathwaite doesn’t have makeup in either photograph, and her expression is powerfully stoic as the light wraps her face leaving the shadow to curve the contours of her jawbone.

In the middle of the exhibition space, the DIA also has a display of the actual dresses that Kwame styled for his models. The “Black is Beautiful” movement wasn’t just about hairstyles, but also African-centered ancestral clothing as opposed to standard American fashion. Seeing the actual clothing there along with the photographs of the models synchronizes and punctuates the collection as a whole. It breathes life into the viewing experience outside of the frames. The apparel was inspired by what was worn in cities like Accra, Lagos, and Nairobi.

Kwame Brathwaite, Sikolo Brathwaite wearing a beaded headpiece by Carolee Prince, ca. 1967

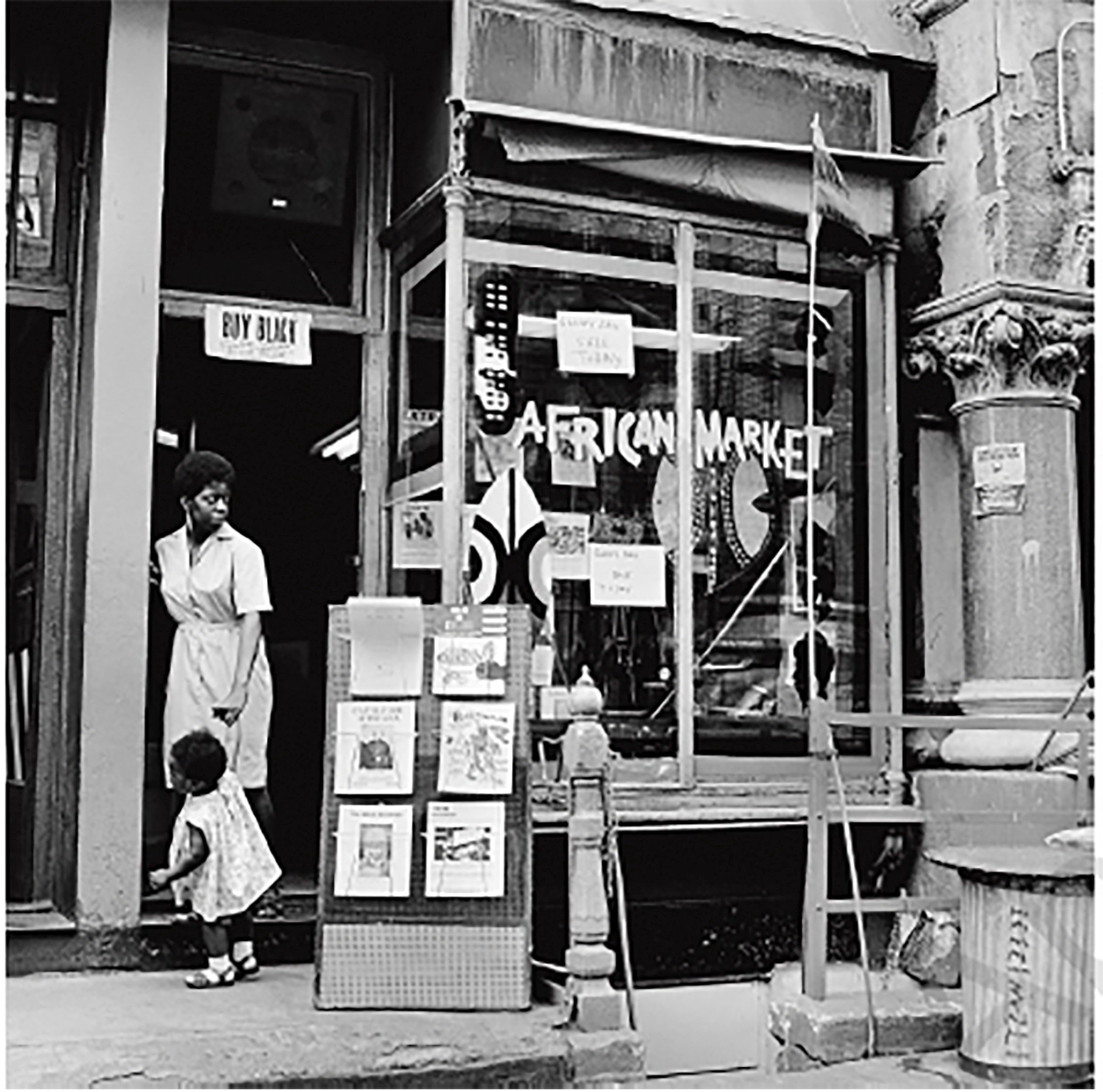

Brathwaite’s documentary work of the “Buy Black” movement from the 1960s is the second theme explored in this collection. The “Buy Black” movement was a branch of black activist Marcus Garvey’s tree of black nationalism in which blacks were encouraged to buy goods and services from one another to build their own economic empowerment. It’s clear that Brathwaite is acting as a messenger journalist. “This exhibition hits on a lot of points in regard to black femininity, black culture, black history, and social activism. Kwame really believed his photography was a tool for social activism and he really needed to record the things that were going on,” Barr says.

The focus in this photo is not the speaker but the Buy Black sign that sits in front and above a blurred attendee’s head at a rally. This was a constant in Brathwaite’s approach.

Kwame Brathwaite, Charles Peaker speaking on 125th street. Peaker became the head of the African African Nationalist Pioneer Movement after its founder, Carlos Cooks, died. Harlen, ca. 1967

In the center of the photograph of a man at an earring counter, there is a “Buy Black” poster. The viewer’s eyes are drawn right to it because the man’s hand is adjusting the earring rack right below the poster. Again, Brathwaite is very intentional with the messaging and this photograph is one of the most well-composed of the collection.

Brathwaite’s photograph of a dark skin black woman holding a child’s hand at the entrance of an African market pulls two of Brathwaite’s themes together. The woman is wearing a natural hairstyle as a Buy Black poster hangs from the doorway above her head. There’s a poster on the window that says, “Garvey Day Sale” along with various African-inspired items in the window.

Kwame Brathwaite, African Market, Harlem, ca 1967

The third tier in Brathwaite’s exhibition is the photographs of Jazz greats and the Harlem nightlife. Many of the photographs are great captures of musicians in their element such Miles Davis and Paul Chambers performing under the harsh glow of stage lights, drummer Max Roach playing the drums, and Abbey Lincoln singing like her life depends on it.

Kwame Braithwaite, Abbey Lincoln Singing at an AJASS event, Harlen, ca 1964

Kwame Braithwaite, Miles Davis and Paul Chambers, Randall’s Island Jazz Festival, ca 1958

What makes Brathwaite’s images of Harlem’s nightlife so energetic is the composition. The way the man has his head supported by his hand as the smoke from his cigar trickles towards the top center of the frame is simply cool. Seeing nothing but the silhouette backs of the jazz quartet feels more intriguing than if the photograph was of them performing straight on. Even though the front row of faces is blurred in the photograph of the crowd at Randall’s Jazz Festival, the energy of the attendees in the far distance under the halo glow of the lights visually describes what that moment must have felt like.

Although the photographs of black women are the face of the “Black is Beautiful ” exhibition; the viewing experience is catapulted to a higher level because the images of black activism and entertainment tell more of the story of black life in the 1960s. What’s also compelling is how those themes are still in existence in today’s racial climate. The Black Lives Matter movement is relatable to both Black is Beautiful and the Buy Black movements. Western beauty standards are still being defined and questioned today just as much today as they were in the 1960s. Kwame Brathwaite’s portraiture craftsmanship and the way he finds the composition within his documentary photographs act as a time capsule and make “Black is Beautiful” a quintessential exhibition.

The Exhibition: Black is Beautiful: The Photography of Kwame Brathwaite at the Detroit Institute of Arts runs through January 16, 2022.