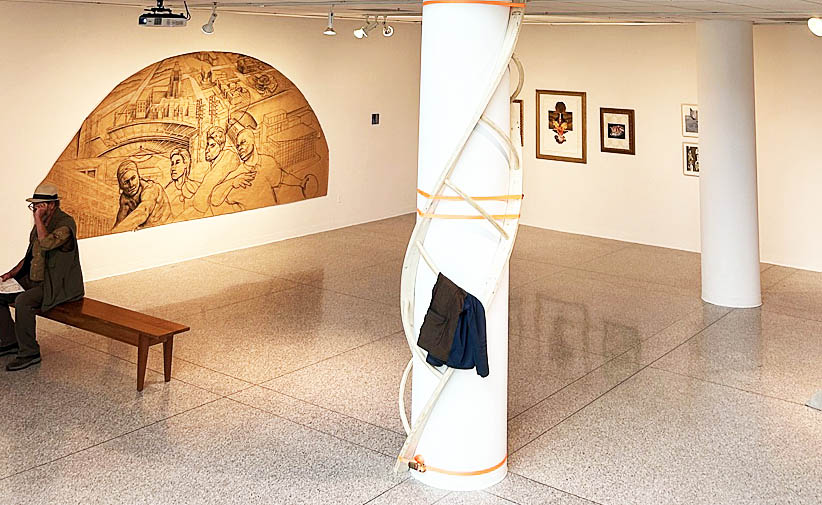

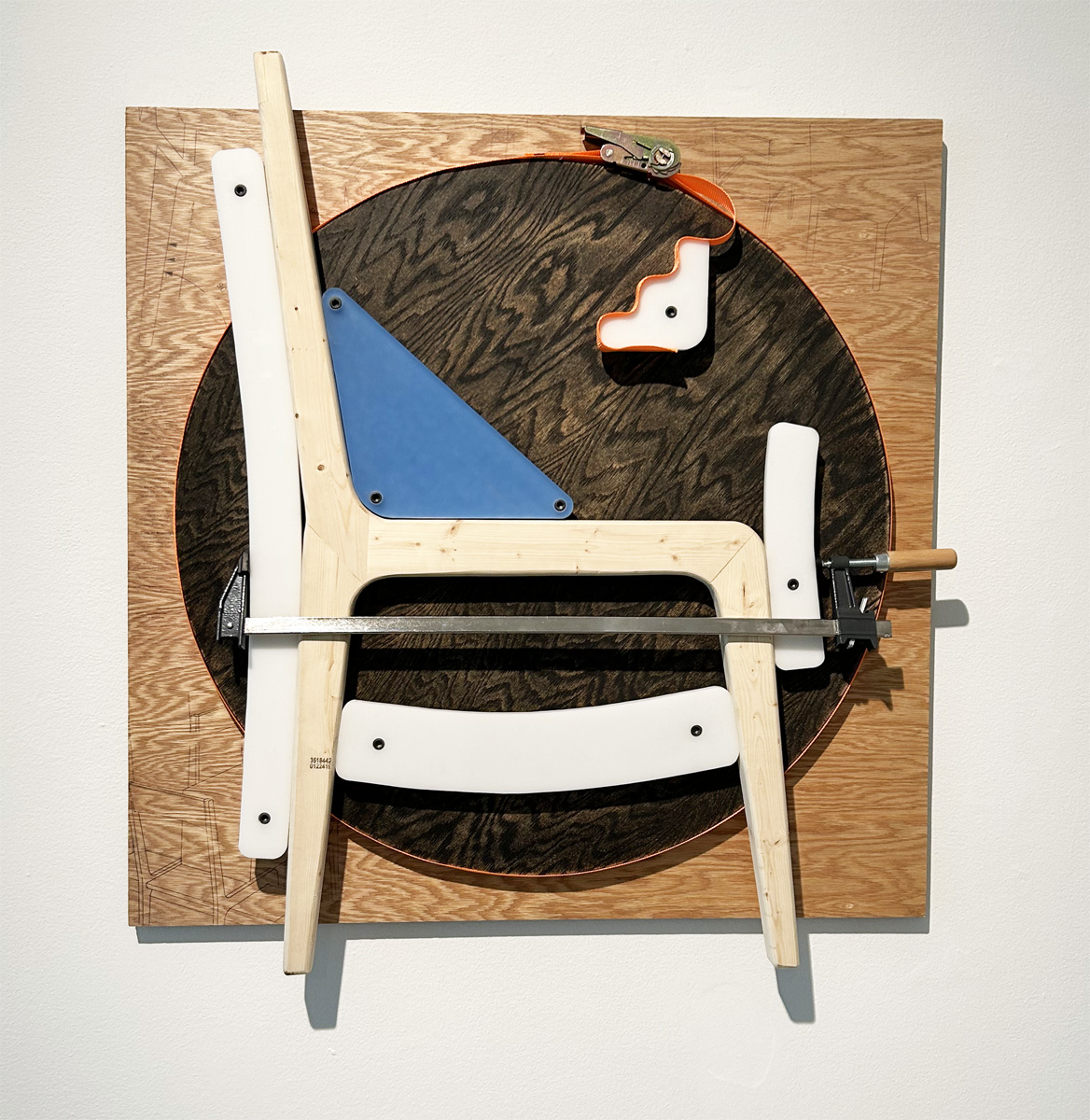

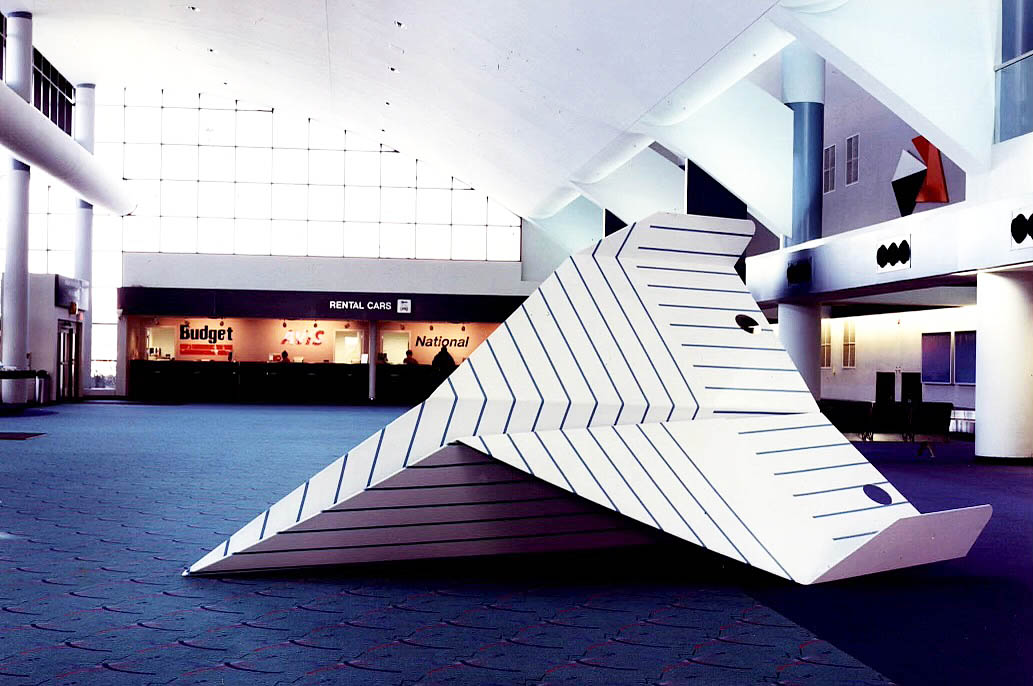

Galerie Camille, Exhibition – The Tyranny of Small Decisions Installation (photo by R Standfest)

Houses loom, and factories downsize at the Galerie Camille in a two-person exhibition of new work by Detroiters Jeanette Strezinski and Ryan Standfest. Enigmatically titled “The Tyranny of Small Decisions,” each artist homes in on a familiar structure redolent of domesticity, work, harmony, catastrophe, safety, loss, reminiscence, oppression, and so on. Entering the gallery, one quickly senses the heady frisson generated by the installation of diametrically divergent works on opposite walls. Stark differences in size and palette, from Strezinski’s monumental black and white paintings to Standfest’s small-scale, multicolored compositions of muted pink, magenta, blue, yellow, and green, draw the visitor back and forth across the space. Media differentiates the work of each artist as well: her tactile, mixed media surfaces (oil, stain, resin, fabric, and construction materials on canvas) and his nubby, textured acrylics on wood panels.

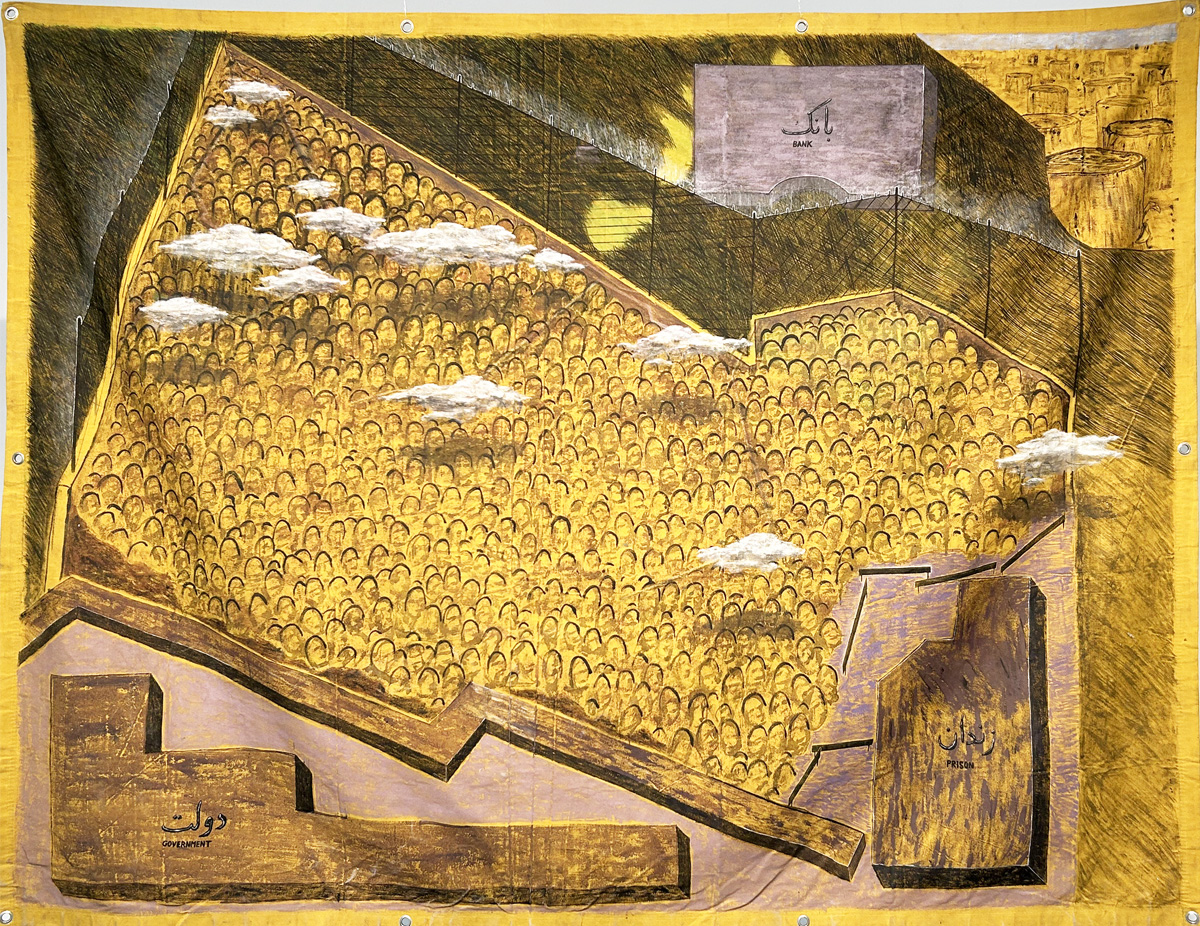

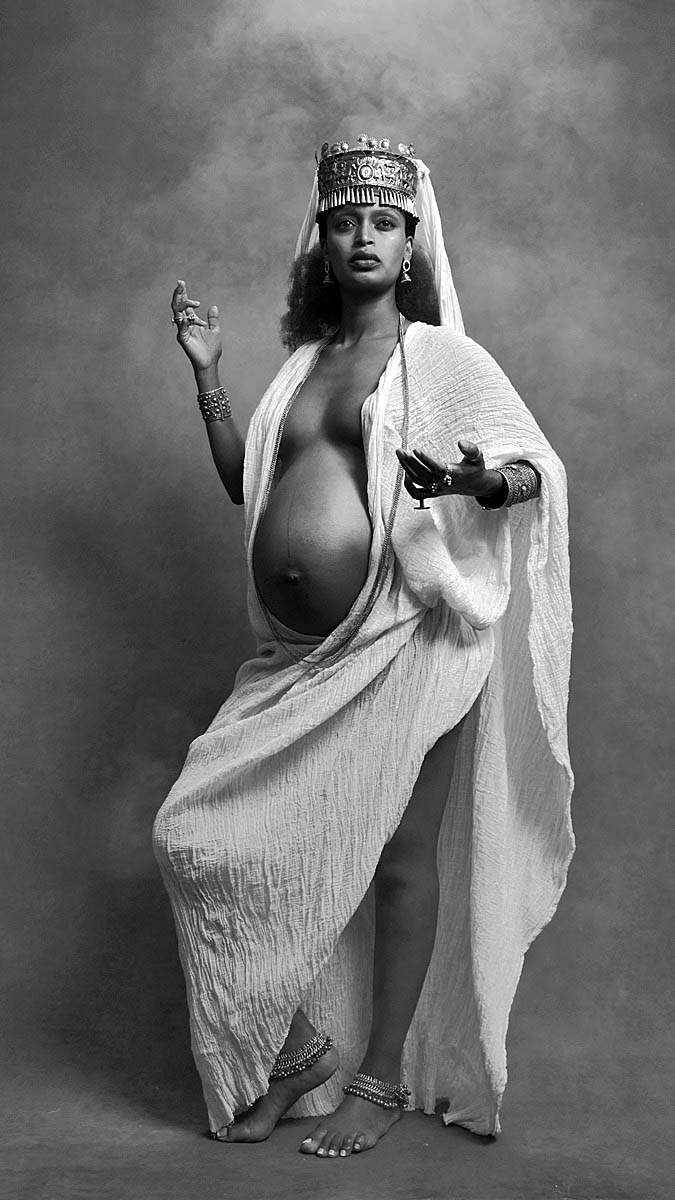

Jeanette Strezinski, Crevices, 2023, Oil paint, stain, resin, fabric, mixed media on canvas, 8 x 9 ft.

Strezinski’s outsize images might be described as documentaries of houses in evolving states of being. Initially, they appear abandoned and ruined, but in reality, several discernible structures overlap one another. In Crevices, at least three gables are superimposed and combined with an unfurnished room at the left. Perhaps renovation is underway with multiple options sketched in by an architect. Like other of her compositions on view, Crevices is built up through a layering of building materials that yield a scratchy, corrugated surface, while its evocative title implies a hint of danger lurking within.

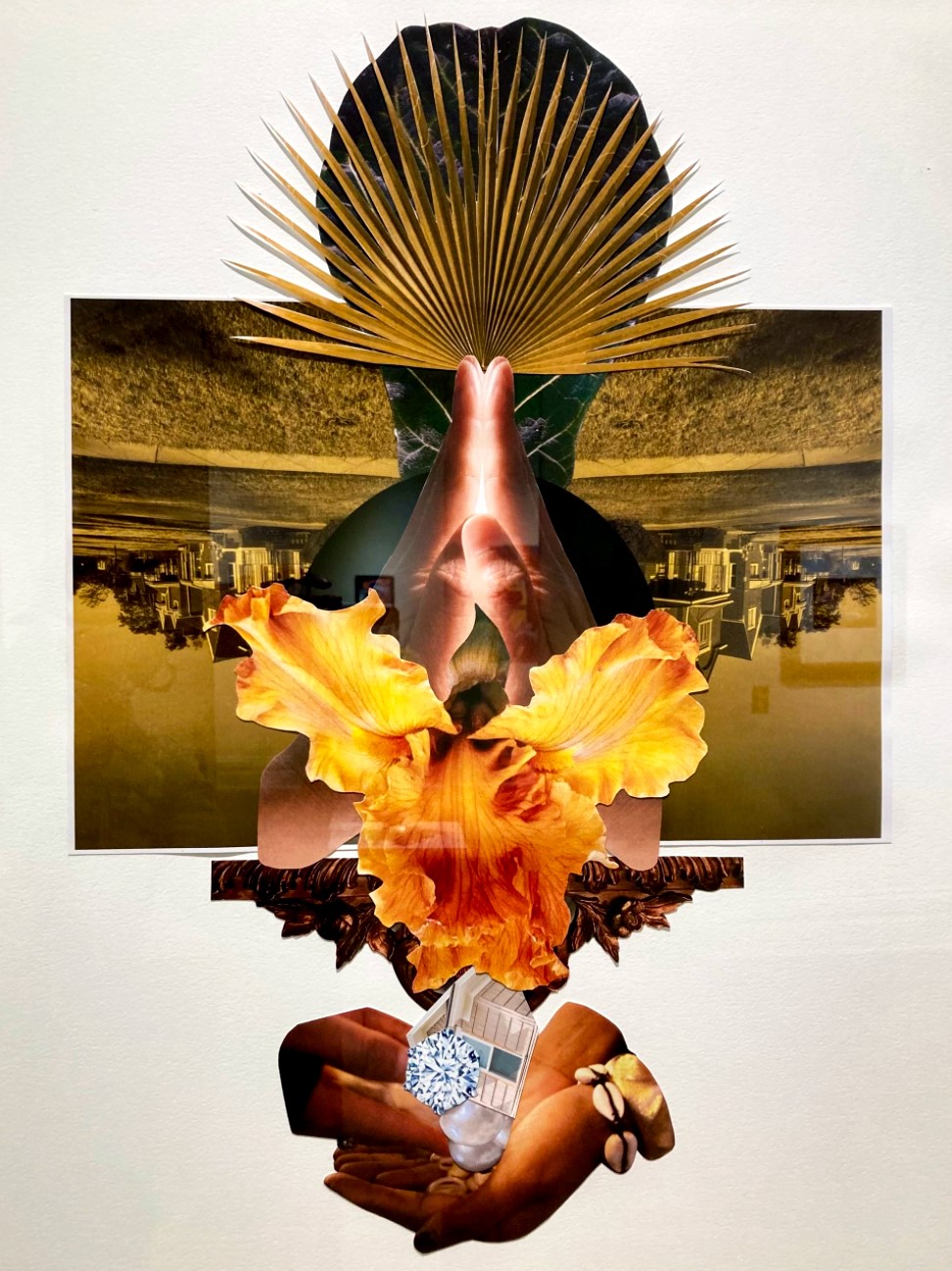

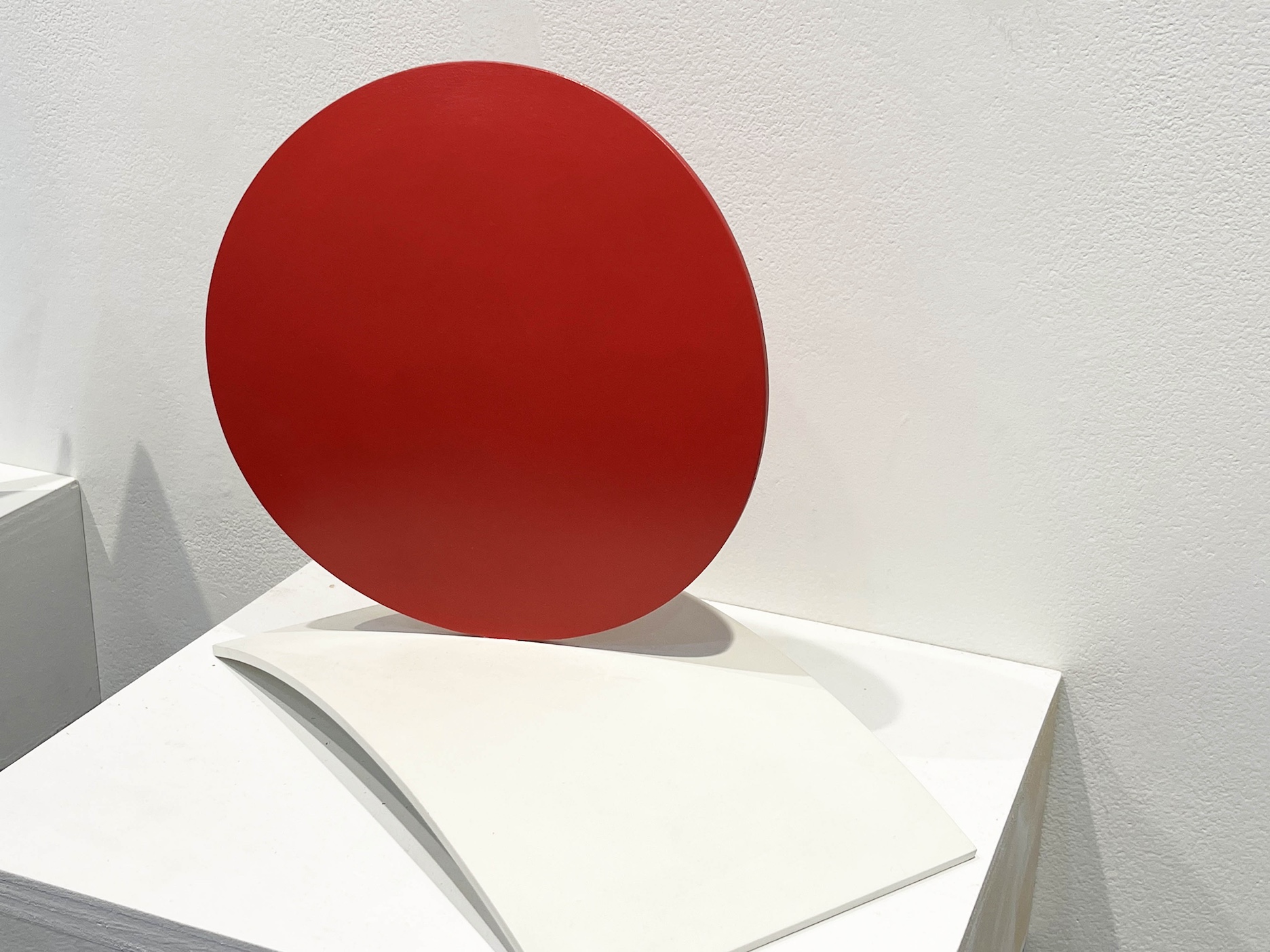

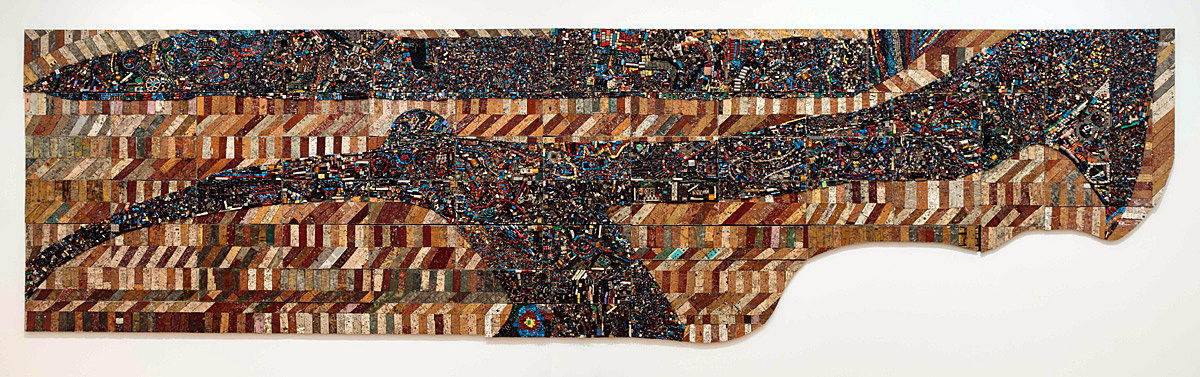

Jeanette Strezinski, Come Home, 2024, Oil paint, stain, resin, fabric, mixed media on canvas, 7 x 7 ft.

Another sizable image on view is labeled Come Home, its titular overtones expressing a plea to return to the traditional, double-gabled house seemingly floating in space. Also visible, however, is a gridded skylight addition at right and deck at left that suggest remodeling and/or deconstruction, as well as an overlapping horizontal ranch house stretched out at the bottom of the white outline that envelopes the artist’s centralized image.

Jeanette Strezinski, Leave The Light On, 2024, Oil paint, stain, resin, fabric, mixed media on canvas, 36 x 48 in.

Leave The Light On, a smaller canvas by Strezinski, is the darkest of her paintings, in which an illuminated window at left glows with yellow light. It alludes affectingly to other iterations of the title in songs and texts that likewise refer to a lighted window as a beacon of home, hope, human presence–or absence.

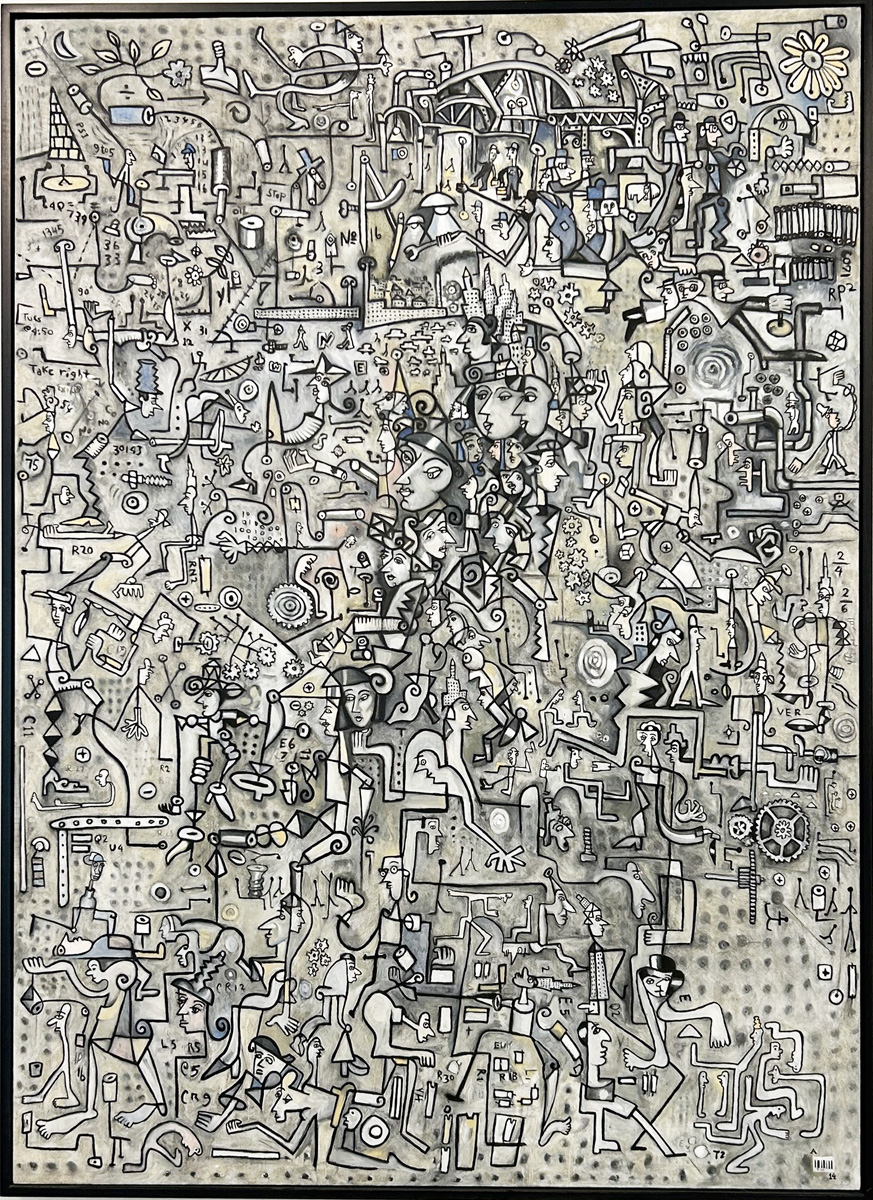

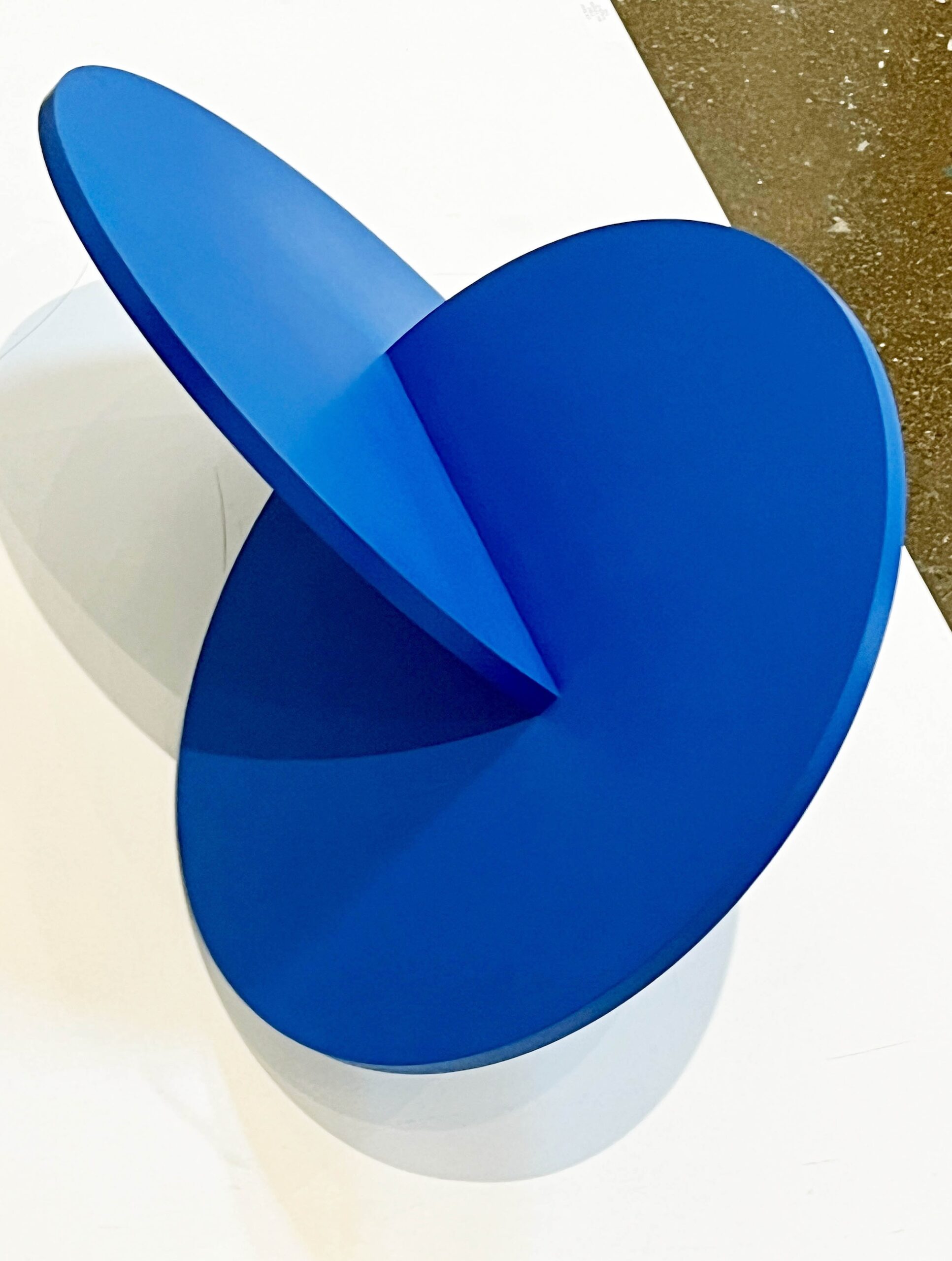

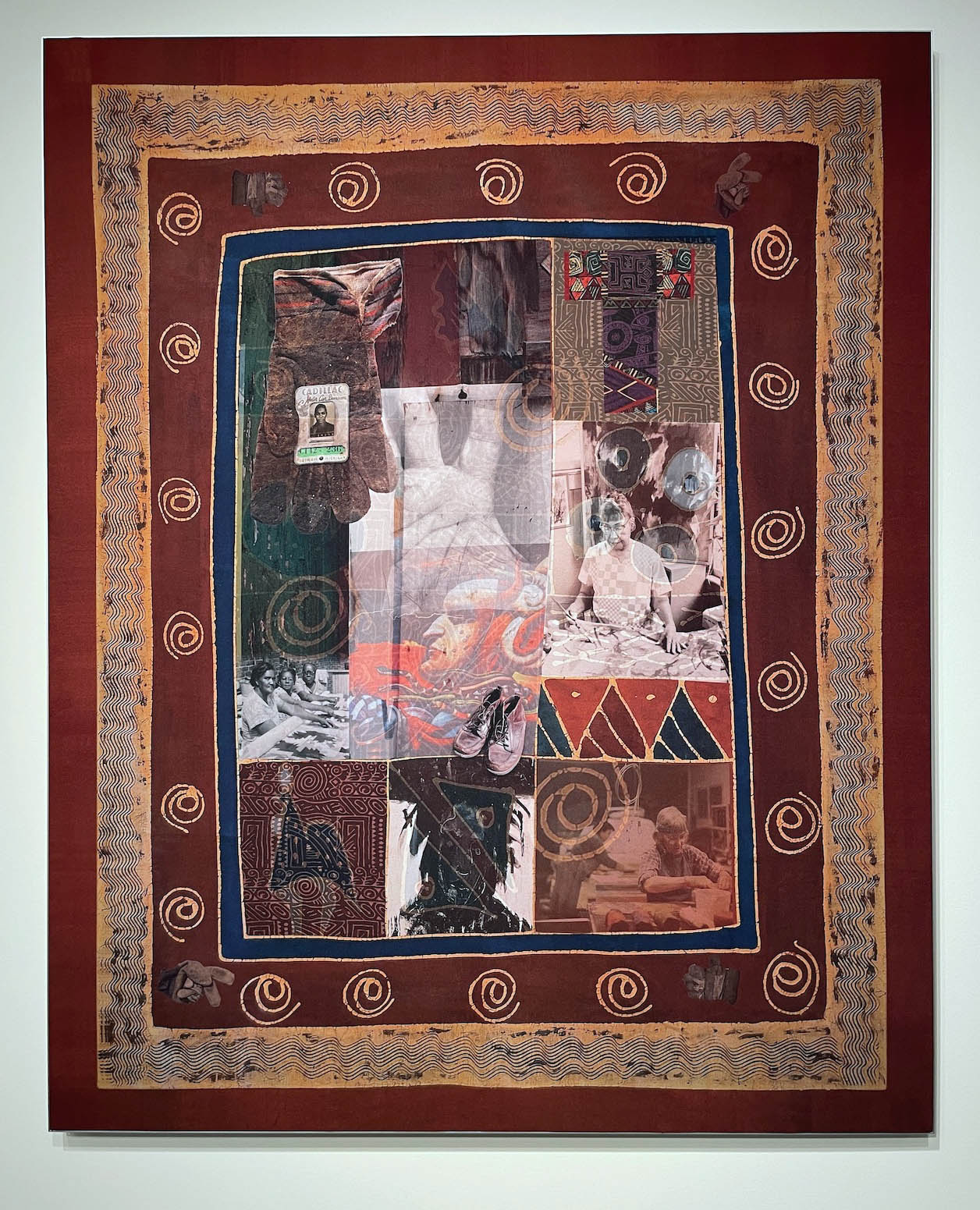

Ryan Standfest, A System of Love, 2024, acrylic on wood, 16 x 20 in. (photo by artist)

Unlike the frontal impact of Strezinski’s looming houses, Standfest’s modestly sized, framed, precisely rendered images on the other side of the gallery feature the factory as the potent focal image. Presented from a bird’s eye point of view, A System of Love depicts an industrial complex of identical structures topped with identical smokestacks rendered in magenta, pink, green, red, and blue. The tidy, rust-free environment is abuzz with blank speech balloons linking various buildings and workers therein. Are they textless because the workers have nothing to say to one another or because they uniformly echo the prescribed messages of an industrialist’s point of view?

Ryan Standfest, A Perfect Engine of Longing, 2024, acrylic on wood panel, 14 x 11 in. (photo by RD Rearick)

As the series develops, Standfest’s silent, anonymous factories are personified, enlarged, and activated, becoming engaged in capitalist machinations. In A Perfect Engine of Longing, the smokestack, like a dagger, pierces a green hillside, further despoiling the surrounding landscape of wizened shrubs and trees.

Ryan Standfest, A Personification of Romantic Fiction, 2024, acrylic on wood panel, 14 x 11 in. (photo by RD Rearick)

And in A Personification of Romantic Fiction, an agile, upside-down factory births another. The newborn, white-hued “infant,” devoid of a full complement of windows and doors like those of its green and blue factory “mother,” connotes the future. More such birthings will produce X number of manufacturing centers ad infinitum. In his artist’s statement, Standfest warns that these “terrible buildings manifest our capacity for creation and catastrophe.”

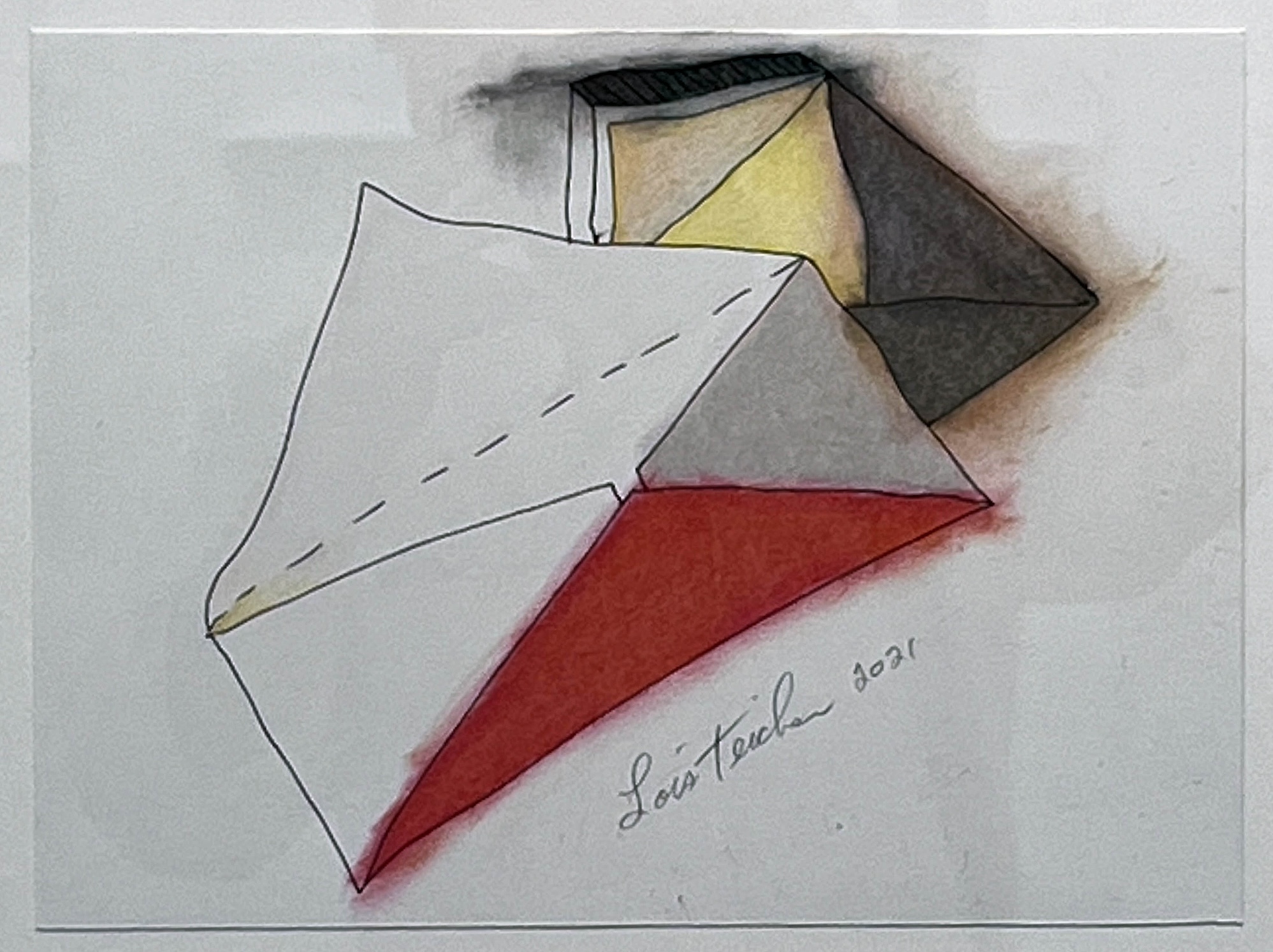

Ryan Standfest, Company n. 2, 2024, Mixed media, 14 x 9 x 5 in. (photo by RD Rearick)

Detail of Company n. 2, (photo by RD Rearick)

Standfest’s oeuvre also includes a series of miniaturized sculptures of industrial buildings, as in Company n. 2, one of four displayed in the show. Each is composed of a rectangular enclosure and tall exhaust element, appears to be abandoned, and exhibits worn, mottled surfaces of various hues, as in the black and rusty red patina of n. 2. One also discovers in the empty window and door apertures, tiny, prone figures, perhaps resting, exhausted, or comatose.

In short, Strezinski and Standfest’s fraught, complicated depictions of vital human habitats, such as homes and factories, address mutual concerns despite their quite distinctive styles of art. As Strezinski observes, in a statement pertinent to both, “My paintings represent dwellings designed for safety and comfort that eventually break down.”

“The Tyranny of Small Decisions” featuring Ryan Standfest and Jeanette Strezinski” remains on view at Galerie Camille through Nov. 29, 2024. The gallery is located at 4130 Cass Avenue in Midtown Detroit.