Whitney Museum of Art Biennial 2022, Installation image

The Whitney Biennial is the longest-running survey of American art and has been a hallmark of the Museum since 1932. Initiated by the Museum’s founder Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney as an invitational exhibition featuring artwork created in the preceding two years, the biennials were originally organized by medium, with painting alternating with sculpture and works on paper. Much has evolved over the years and this year the Biennial comes after being postponed because of the pandemic. The spaces here contrast significantly, acknowledging the acute polarities in American society. One floor is a labyrinth, a dark space of containment and another is a clearing, open and light field. The subtitle of this year’s Biennial is Quiet as it’s Kept, is a colloquialism. The quote comes from the writer Toni Morrison and is said prior to something, often obvious that should be kept a secret. The curators, David Beslin, and Adrenne Edwards have been entrusted with making the exhibition that resides within the Museum’s history, collection and reputation. This is the 18th iteration and continues to function as an ongoing experiment.

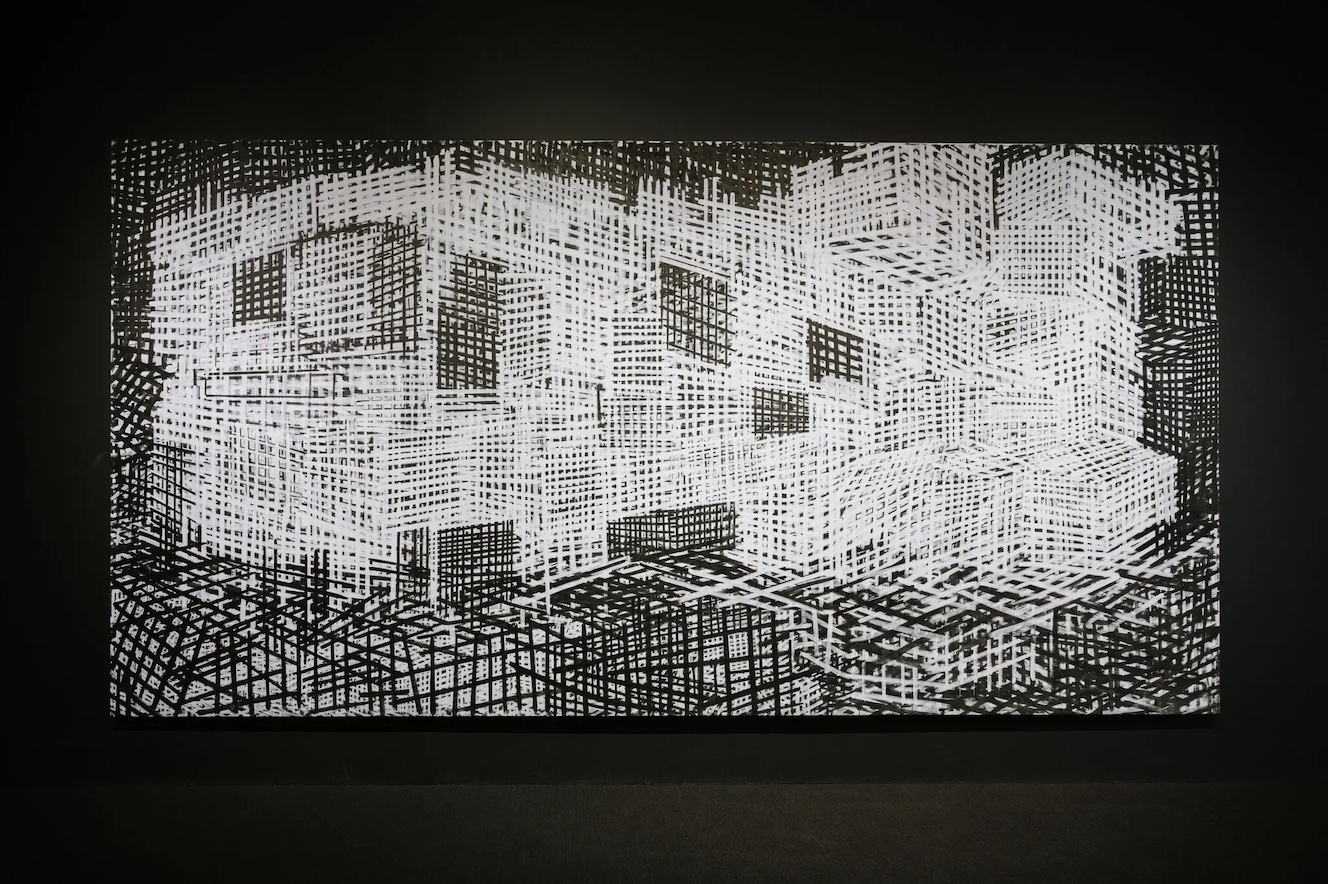

Denyse Thomasos, Displaced Burial/Burial at Gorée, 1993.

The sixth-floor section of the Biennial opens with two large-scale abstract works by the late artist Denyse Thomasos, who died in 2012 at 47. For these striking works, Thomasos was interested in creating the sense of claustrophobia felt by enslaved people crossing the Atlantic crossing and inmates being held in prisons. Her goal was “to capture the feeling of confinement,” she once said, per the wall text, as a way to explore how structures like ships and prisons have “left catastrophic effects on the Black psyche. Her black and white overlapping grids create a feeling of claustrophobia and captivity. There are two twin paintings presented here as the viewer enters a space that is entirely black. Most of this floor is divided up into rooms (all black) that serve as viewing rooms for art videos.

Rebecca Belmore’s sculpture, “ishkode (fire),” 2021

At the Whitney Biennial, center, the Indigenous artist Rebecca Belmore’s sculpture, “ishkode (fire),” 2021, made from clay and bullet casings. The Anishinaabe artist Rebecca Belmore—who was the first Indigenous artist to present Canada at the Venice Biennale, in 2005—made this commanding ceramic sculpture from a sleeping bag cast in clay and surrounded it with an arrangement of empty bullet casings. The work, a critique of the historic genocide and ongoing disproportionate violence against Indigenous people, is a centerpiece of the sixth floor of the exhibition, illuminated from above in the otherwise darkened space. “The work carries an emptiness,” the artist writes. “But at the same time, because it’s a standing figure, I’m hoping that the work contains some positive aspects of this idea that we need to try to deal with violence.” In the background, Guadalupe Rosales’s photographs of East Los Angeles, 2022.

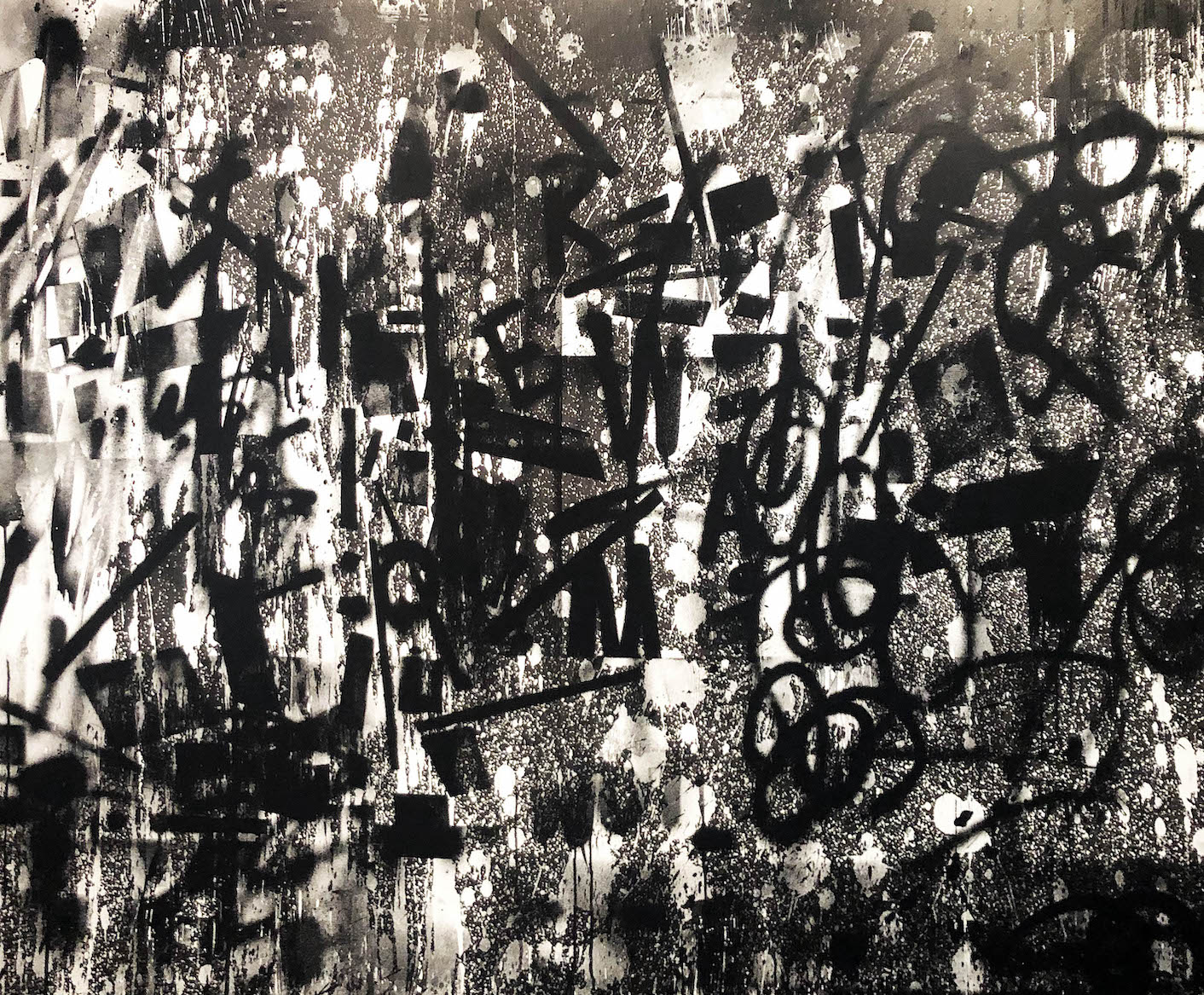

Daniel Matinez, Post Manifesto for the Future, 2022

There are five photographs that document what Daniel Joseph Marinez has described as “radical performative experiment of becoming post-human and the evolution of a new species.” Martinez used his own body to interrogate and bear witness to the extraordinary moment in human history, our own self-destruction.” The recent abstract paintings on view here involve a process of accumulation in which the surface of the canvas is constructed of sweeping gestures, letters, drips, splatters, and moments of erasure is a reflection of how we evolve in life. The black and white silkscreened work of marks and impressions tries to articulate who we are or who we might be at any given moment: a kind of visual poem or disruption.

Adam Pendelton, Untitled 2021

Ralph Lemon is an interdisciplinary artist who works primarily in performance and has made drawings throughout his life. For the Biennial he has created a choreography of work that is presented in a group and moves throughout the exhibition in a circle. Every so often the work moves to a new position in the collection. Themes range from elaborate visual mediations and the nature of the artistic process itself to experiments refracting Black American culture, icons, music, and joy. It is fair to say this is an installation of images that changes its position during the exhibition.

Ralph Lemon, One of several from an untitled series, that changes. 2022

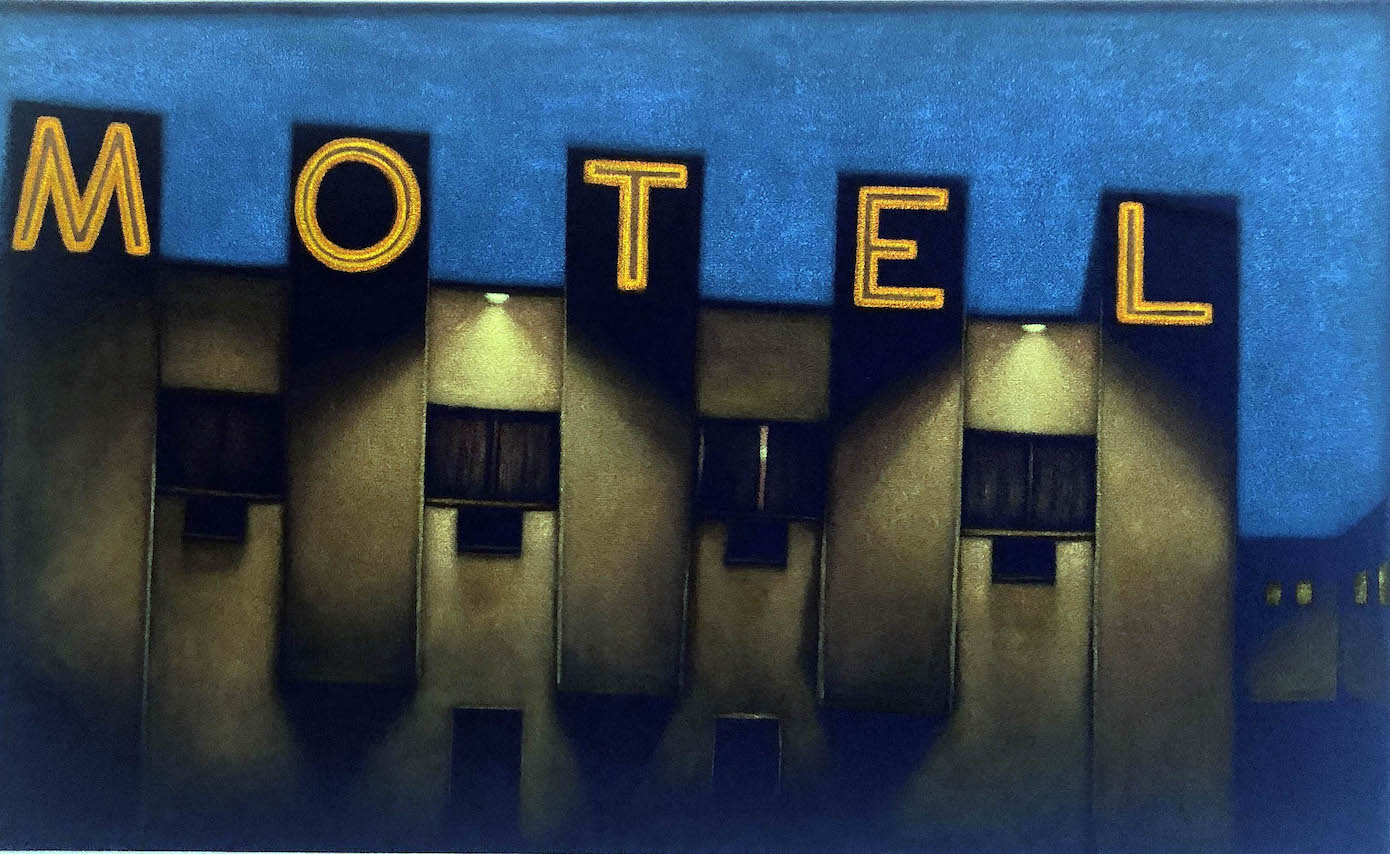

There are five paintings by Jane Dickson who shares the hopes and aspirations that commercial signs convey both in contemporary suburban spaces she photographed in New York City during the 1980s. The Motel is one of the five. Dickson’s careful depictions suggest that certain violence comes with making generalizations in the writing off of those who lead their lives in the areas that are frequently overlooked or dismissed. In her statement she says, “I chose to be a witness to my time, not to document its grand moments, but to capture the small telling ones, the overlooked everyday things that define a time and place.

Jane Dickson, Motel 5, Acrylic on Felt, 2019

Coco Fusco, Your Eyes Will Be an Empty Word, 2021.

In this new video, Coco Fusco directly reflects on the death toll caused by the pandemic. We see her in a boat just off Hart Island, near the Bronx. The island has long been the site of New York City’s potter’s field, where unclaimed bodies are buried. At the height of the AIDS crisis in the ’80s and ’90s, many bodies of people whose families had disowned them were sent here; over the past two years, it has again become active at an alarming rate. Fusco tapped poet and writer Pamela Sneed, an AIDS activist who penned a 2020 memoir Funeral Diva about that era, to provide the narration—written by Fusco—for this poignant mediation on death, loss, and grief. Over the course of 12 minutes, Sneed tells us that there could be as many as a million bodies buried here, but no one accurately knows. With the staggering total death totals from Covid, she notes, bodies become numbers in ways that make us forget the stories of those who are lost. Throughout the film, like a chorus, Sneed repeats, “‘When death comes it will have your eyes,’ he said.”

If you are visiting New York City before September 6, 2022, it is always a good experience to see what is going on around the country. Something worth note is there are four indigenous artists represented from various parts of Noth America. The exhibitions are on floors, 1, 3, 5, and 6.

In Summary, I would agree with the art critic Peter Schjeldahl who says “ long on installations and videos and short on painting, conventional sculpture, and straight photography.” When he writes for The New Yorker. Whitney Biennial 2022