An installation view of Luminosity: A Detroit Arts Gathering will be at Detroit’s Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History through March 31, 2026. (Courtesy of the Wright Museum. All other images by Detroit Art Review.)

Long before the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History took up residence in its spectacular building in Detroit’s Cultural Center, it started life on West Grand Boulevard in 1966 in a building owned by Dr. Charles H. Wright himself. To celebrate this sixtieth anniversary, the museum has mounted a large, dazzling show, Luminosity: A Detroit Arts Gathering, an exhibition of Black art by Detroiters past and present that will be up through March 31, 2026.

Organized by freelance curator Vera Ingrid Grant in Ann Arbor, previously a curator at the University of Michigan Museum of Art as well as a Fulbright Scholar in Germany, this expansive historical survey features 97 works by 69 artists. Included are superstars from the past, like Hughie Lee-Smith and Al Loving, giants of the contemporary Detroit art world such as Allie McGhee and Carole Harris, and relative newcomers like Akea Brionne and O’Shun Williams.

Grant says Wright officials were looking for “a celebration of the museum and its ties to the community,” a challenge that thrilled her. Given the celebratory nature, she adds that it was important to her to highlight joy in African-American life. There are images of despair, to be sure — like Jonathan Harris’ sharp-edged painting of the classic photo taken moments after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was shot — but Grant wanted to make sure that gloom and tragedy did not overwhelm.

Sydney James, The Westside Johnsons, Acrylic on raw canvas, 72 x 120 x 1/10 inches, 2023.

This point of view hits you right as you enter Luminosity and behold Sydney James’s large, color-filled canvas, The Westside Johnsons. A buoyant portrait of an extended family set against a rich red background, the painting fairly radiates affection and joy, with not an ounce of sappiness to it. These 12 Johnsons are so individualized and real, you feel like you could start a conversation with any one of them right there in the gallery.

James, a muralist with outdoor work around Detroit, put fringes on the edge of the painting (sadly not visible in the image above), giving the composition some of the feel of a quilt, with all the folk implications that carries. Grant loves the work, calling it “gorgeous,” adding that she chose it for the entryway to set the mood for the whole exhibition.

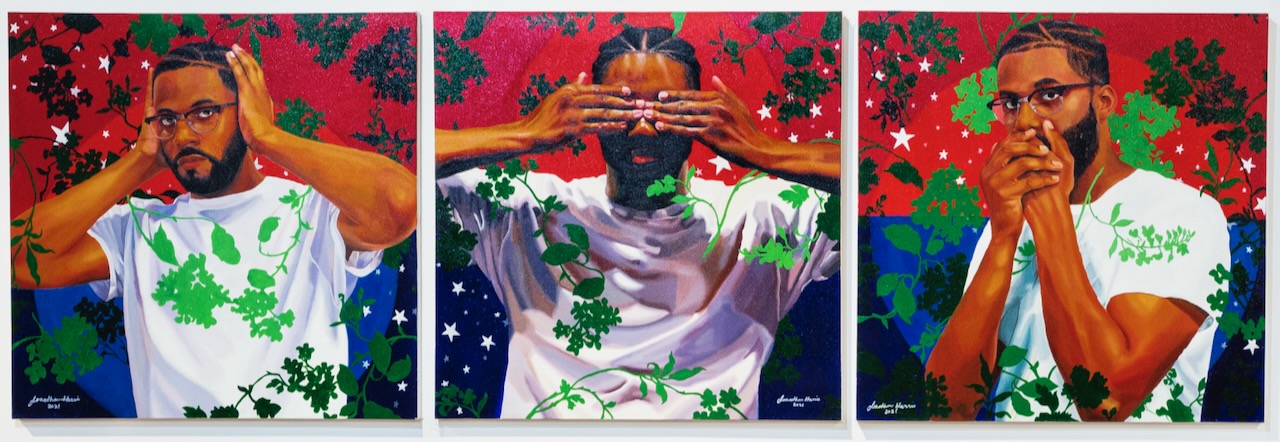

Jonathan Harris, Hear no evil, See no evil, Speak no evil (Triptych); Oil on canvas, 36 x 36 x 1½ inches; 2021.

These three panels by Jonathan Harris invoke the classic proverb, originally derived from Japan, and star the artist himself in black glasses and a white t-shirt, acting out the gestures every child knows and will readily imitate. Harris has positioned himself in front of a strongly colored background – the bottom half a sort of starry nightscape, and the top half a uniform deep red with stars scattered here as well. Strewn over the compositions are strands of bright-green ivy that crisscross the artist’s shirt and, in the last case, frame his head.

Harris, a graduate of the Detroit School for the Fine and Performing Arts and Oakland University, notes in his artistic biography that he utilizes “an oil enamel technique, resulting in graphic, high contrast portraits, without the use of a brush.” The result with Hear no Evil… is a trio of powerfully magnetic paintings, ones that are almost impossible to ignore. “The audience is definitely drawn to them,” Grant says, “as well as to what he’s expressing, and his accessibility in a psychological space.” Underlying all Harris’ work, she suggests, is the question of “how we in Detroit manage life in these United States.”

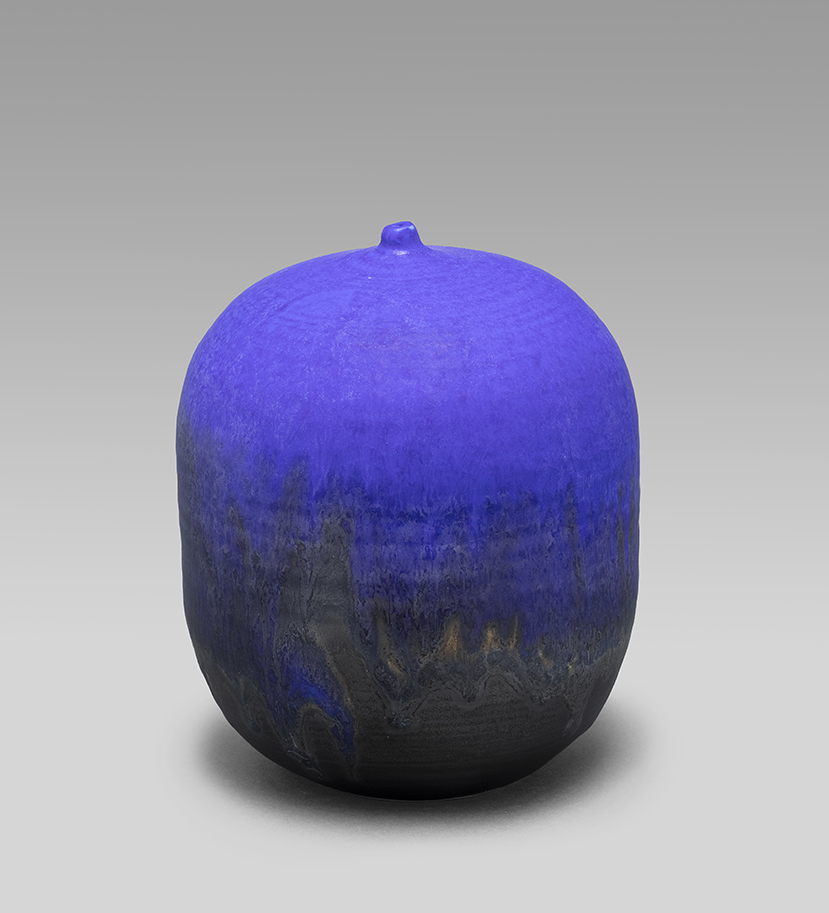

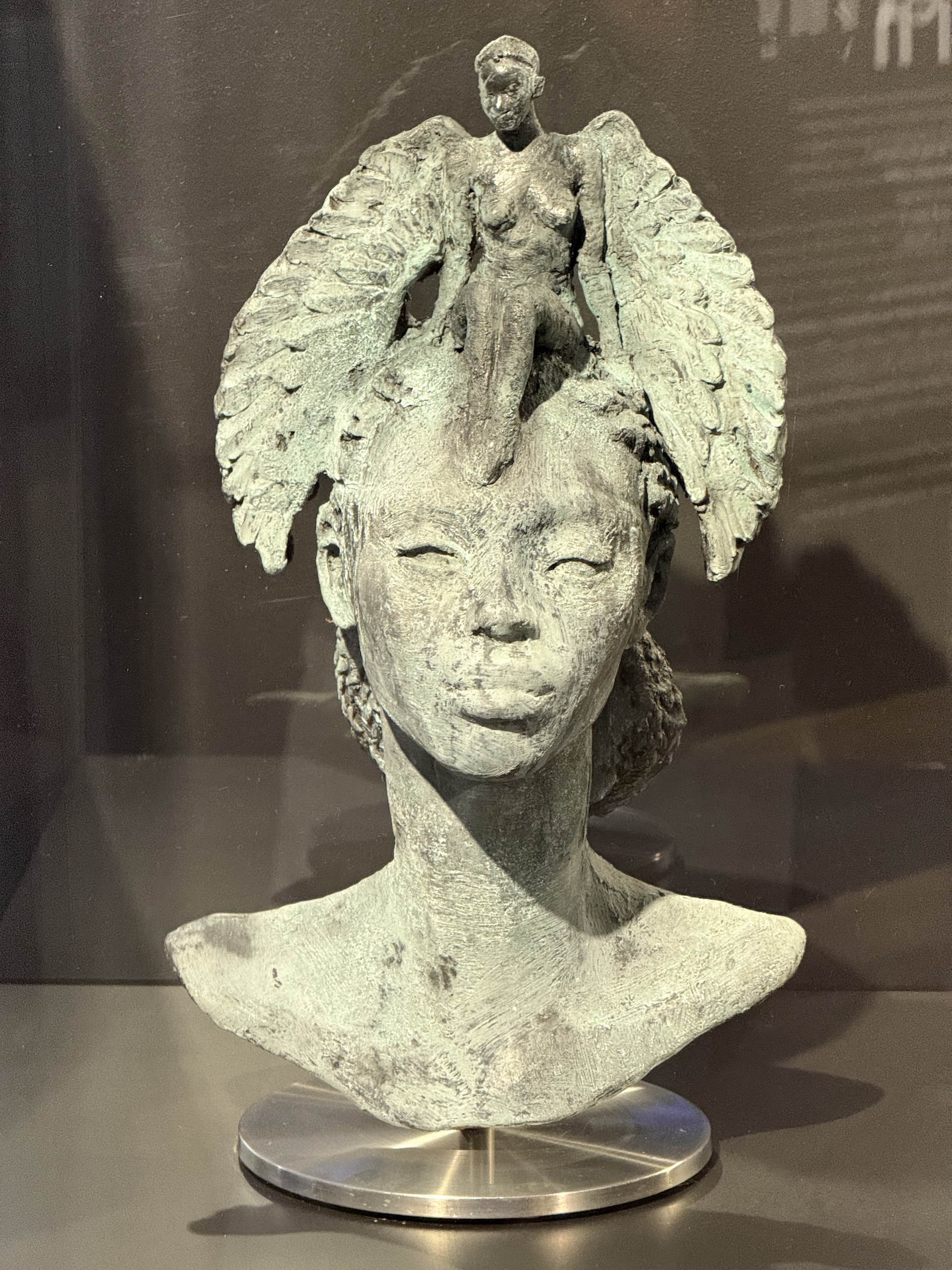

Austen Brantley, Watch Over Me, Ceramic, 28 x 12 x 12 inches, 2025.

The ceramic sculpture Watch Over Me by Austen Brantley, a 2023 Kresge Artist Fellow, is both whimsical and striking with its bust of a handsome young Black woman with an angel perched atop her head, wings framing the girl’s face. Given the craftsmanship (which actually reads like metal, not ceramic), it’s shocking to learn that Brantley, chosen last year by the city of Detroit to sculpt boxer Joe Louis, is an entirely self-taught artist.

Grant particularly admires a certain rough, unfinished quality to his approach. “Brantley’s developed an ability to stop work in the midst of something that’s still raw,” she says. “It just kind of lets you in, in a way that a fine-tuned, fully-refined sculpture emitting a kind of glossiness would not.”

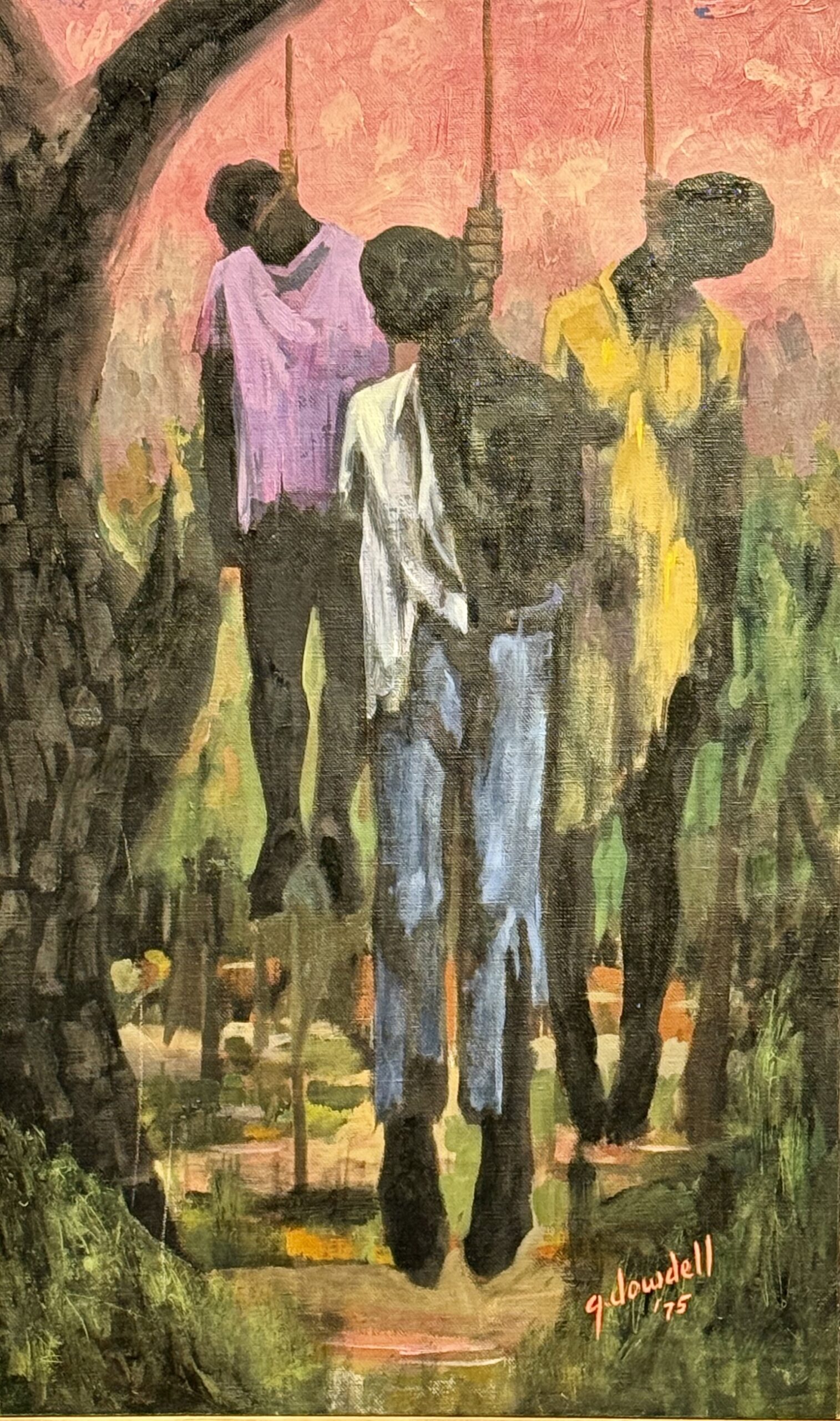

Glanton Dowdell, Untitled, Oil on canvas, 40 ¼ x 24 ½ x 1 ½ inches, 1975.

Glanton Dowdell spent 12 years in prison for what Grant calls “a dead-serious crime,” i.e., second-degree murder. Before incarceration, however, he’d been formally trained in painting, but while behind bars, the Detroiter, born in 1924, refined this talent to a remarkable degree.

“Dowdell came out of prison in the midst of the 1960s with everything going on,” Grant says, “and I think he must’ve received a political education there, too,” because, among other things, he co-founded the Detroit branch of the Black Panthers. You can read activism and rage in this untitled portrait of three lynched bodies hanging from a tree, a tragic trio that includes a woman, which is a bit unusual, as well as a man with no trousers. Apart from its grisly subject, what makes this painting especially startling is Dowdell’s choice of pastels for background colors. You might think he intended the juxtaposition to shock, but the hues – a tender rose and soft green – almost read like the artist’s blessing upon the three unfortunate souls.

Eventually, like a number of Black radicals in that era, Dowdell abandoned the United States, in his case moving to Sweden, where he spent the rest of his life. Out of the blue in the 1970s, Dowdell mailed this canvas to the Wright Museum with a note saying, in effect, “Here – this is for you. This is what I’m thinking about in Sweden.” The painting has been in the Wright’s collection ever since.

Tylonn Sawyer, Royal, Charcoal, pastel, and gold leaf on paper, 50 x 36 inches, 2022

Tylonn Sawyer, a 2017 Kresge Artist Fellow, gives us one of the most magnetic portraits in the entire show with Royal. This painting of a young Black woman amounts to a high-concept composition, indeed. The subject may be wearing jeans and high-top sneakers, but her aura, as Grant notes, is anything but pedestrian. “He’s presenting her in her ordinariness,” she says, “but her stance is regal, and he’s given her this golden backdrop and a kind of asteroid behind her.”

That heavenly body streaks through a horizontal black band that divides the painting in two, framed above and below by textured, hard-to-take-your-eyes-off gold leaf. It’s a remarkable artistic conceit, one that lifts this work way beyond the expected.

“It’s a surprise,” Grant says. “What would you normally see in a royal portrait? You’d see the individual’s treasures, their symbolic pieces — but her backdrop is this kind of universal sky with a comet going by. That’s the disjuncture, right? It makes it startling.” Grant always saw this as one of the key works for the show. “It stands in for the things I’ve tried to share about joy,” she says, adding, “It captures the luminosity of Detroit.”

Luminosity: A Detroit Arts Gathering, will be up at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit through Mar. 31, 2026.