Installation image of FIA exterior

The Flint Institute of Arts is not an enormous museum, but it delivers a big experience. One of the wonders of the FIA is how they manage to do so much in a relatively small space. The museum boasts a dozen galleries featuring a spectrum of objects from across the ages and around the world; notable contemporary glass and ceramics galleries; a showcase-lined corridor devoted to decorative arts; a theater and a sculpture court; and a small gallery between the obligatory gift shop and cafe that sells work made by students from the adjacent art school. At the very back of the building is the Sheppy Dog Library (named for philanthropist Dr. Alan Klein’s golden retriever), a warm, welcoming reading room stocked with reference books and comfy chairs in which to peruse them.

Installation, From Earth To Sky: Ancient Art of the Americas

Of course, there’s generous space given over to large headliner exhibitions, but there’s also a tiny media arts gallery — a “black box” theater designed to show video works. And just in front of the library is the FIA’s graphics gallery, a dark-walled room with subdued lighting, just big enough to comfortably showcase a dozen or so prints or drawings. All three of these spaces are currently hosting art created by Mexican artists, featuring work that spans two millennia. In the main galleries is the exhibit From Earth To Sky: Ancient Art of the Americas, showcasing ceramic figures and objects from the collection of a Texas oil magnate. The graphics room offers Mexicanidad, a portfolio of twelve prints created by El Taller de Gráfica Popular, a progressive-minded, Mexico City-based printmaking collective founded in 1937. And in the Security Credit Union Media Arts Gallery, they’re showing Pocha Dream, an eleven-and-a-half minute excerpt from the Dream Machine Archive, a “psychodynamic audio and video tool” designed by artist Natalia Rocafuerte to help immigrant women interpret their dreams. (Rocafuerte grew up around the Mexico/Texas border, and became a naturalized US citizen in 2019.)

Ted Weiner was a second-generation oil man who threw himself and a chunk of his fortune into art collecting in the 1950s. He acquired an impressive array of modernist works, as well as a large collection of indigenous Mexican sculptures, which were experiencing a vogue at the time. He was noted for his “catholicity of taste” — which could be taken as a backhanded compliment. But Weiner’s collection of pre-Hispanic ceramics was of such quality that when his daughter offered the complete set to the FIA after his death, the museum (after doing due diligence) gladly accepted it.

Jalisco, Ancestor Pair, ca. 200 BCE – 200 CE Ceramic

Many of the pieces on display here are smallish terracotta figures or vessels from the Nayarit, Jalisco, and Colima regions of western Mexico, created to be buried along with deceased members of elite families, in underground tombs beneath a family’s home. The tombs were accessible by shafts, and often contained the remains of several of a family’s ancestors. To modern eyes, the figures depicted by the sculptures might seem enviably relaxed and relatable: seated on stools, sitting arm-in-arm, smoking, or leaning back with legs spread as if lounging on the beach. But the elaborate jewelry, scarifications, tattoos, headwear, and other features on these figures indicate prestige and authority handed down through ancestral bloodlines. Male-and-female couples sitting side by side are thought to represent the ancestral progenitors from whom a family’s elite status flowed. Some figures have abstracted features to emphasize rank over individual likenesses. Elsewhere in the exhibit, other walks of life are represented; most dramatic are the shaman warriors, dressed in cylindrical armor and outsized helmets, and brandishing clubs. Everyday activities such as playing ball, preparing food and medicines, and giving birth are depicted as well.

Colima, Dog, ca. 200 BCE – 200 CE Ceramic

Dogs were a favorite subject of these sculptures, and ceramic canines were common in the tombs. They’re undeniably cute; one small dog on display here is flopped with its legs splayed out, and another boasts a rotund belly, toothy grin, and even an anatomically correct backside that will charm any dog person. For ancient Mexicans, these dogs held spiritual significance as well; they may have acted as guides for the deceased into the underworld, valued companions in death as they were in life. The chubby “Colima Dog” has since become iconic of the region, and its image has been adopted by contemporary Mexican artists such as Guillermo Ríos Alcalá, whose monumental version of a pair of the dogs dances over a traffic circle in Colima, part of an ongoing process of re-establishing connections to pre-Hispanic culture.

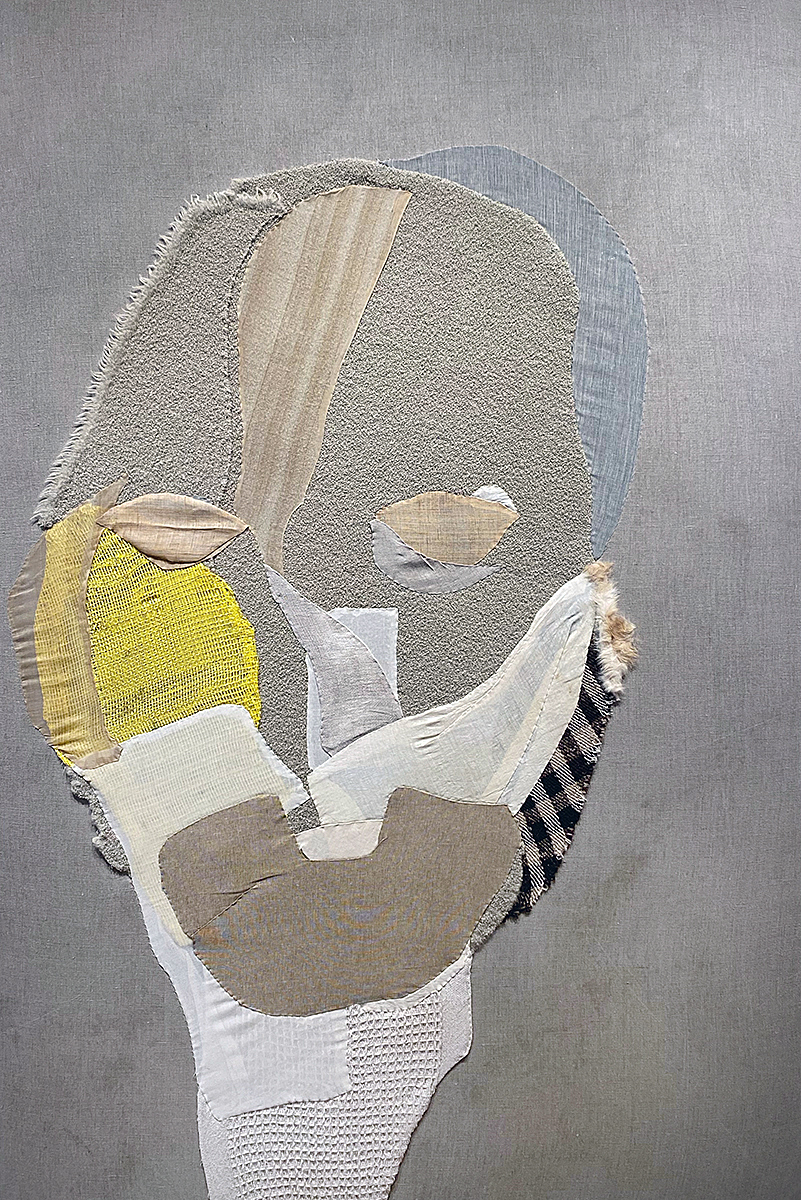

Mexicanidad, Installation view

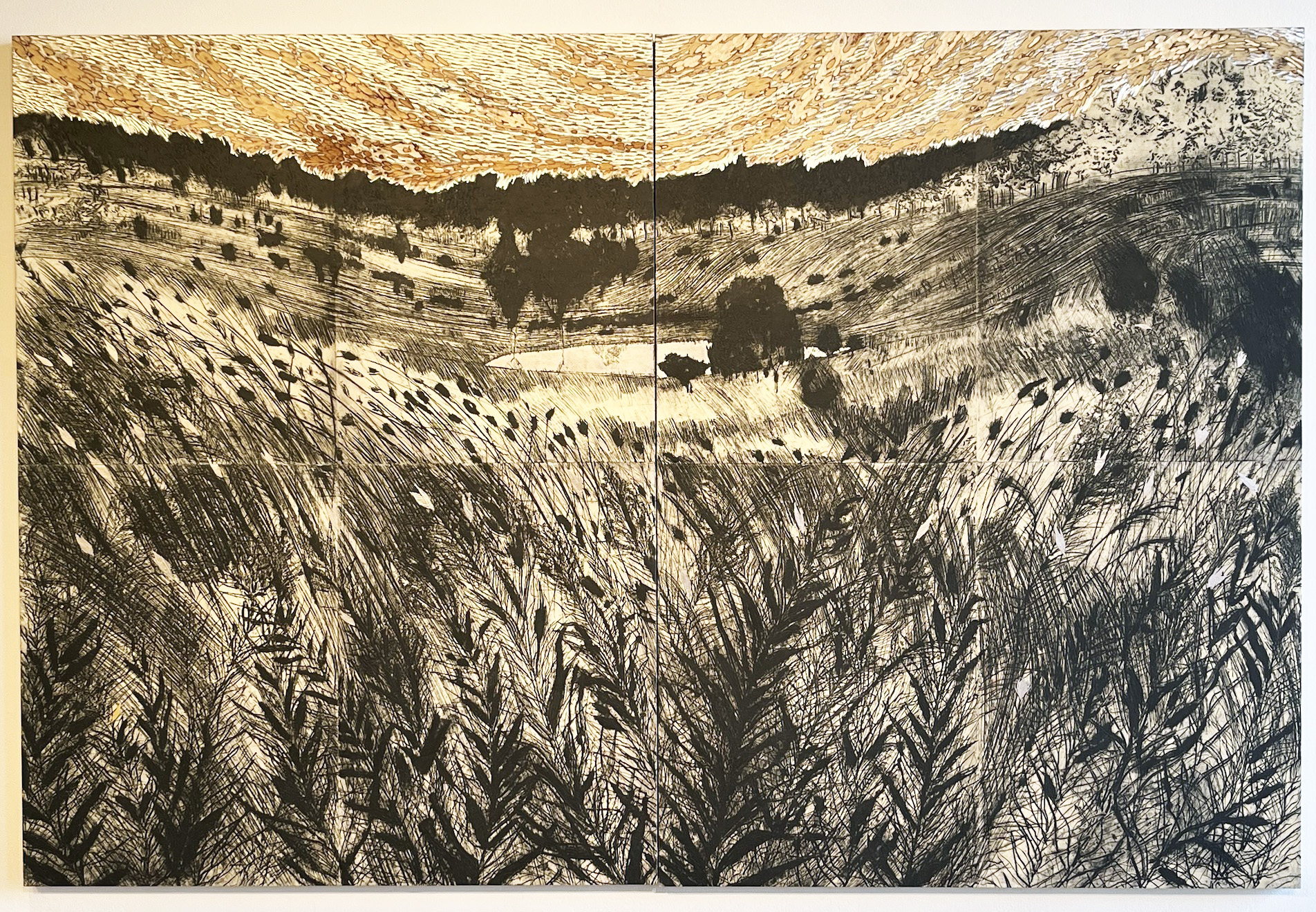

The concept of Mexicanidad (essentially, “Mexican-ness”) links the ancient works in the main gallery with modern ones in the FIA’s print gallery via the post-revolutionary nationalist movement by that name. Most often associated with the mural projects of “Los Tres Grandes” — Orozco, Siqueiros, and Rivera — the Mexicanidad movement had an important printmaking aspect as well, rooted in the social commentary of predecessors such as José Guadalupe Posada. While the “Big Three” educated the people on progressive issues with large-scale public wall paintings, the printmaking collective El Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP) took the opposite tack: creating small, accessible, and affordable artworks, though still with powerful leftist political messaging. The portfolio displayed here, simply titled “Mexican People,” comprises a dozen lithographs produced in 1946 by TGP for the purpose of promoting Mexican products in the United States.

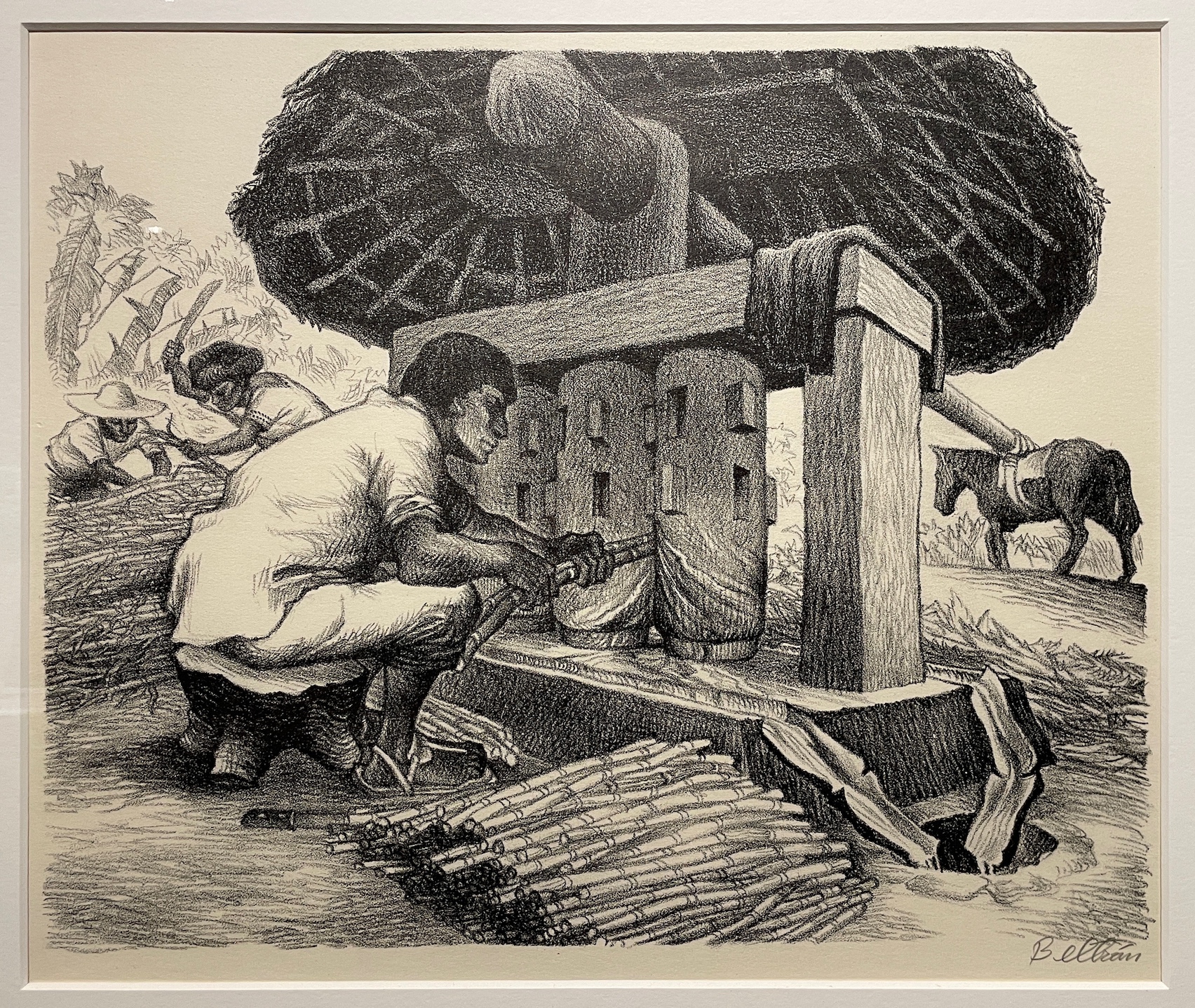

Alberto Beltrán, The Sugar Mill, 1946 Lithograph

Alfredo Zalce, Lumber Workers, ca. 1945 Lithograph

American ex-pat artist Pablo O’Higgins (FKA Paul Higgins before becoming an assistant to Diego Rivera) contributes two prints, one of a man and child stacking bricks, and another of an older woman selling her wares at market. O’Higgins employs heavy, sinuous lines that lend his subjects both muscularity and grace. Alberto Beltrán’s image of a man feeding sugar cane into a donkey-driven mill is as elegant as it is diagrammatic, concisely describing the process in a masterfully composed image. Alfredo Zalce’s litho of a lumber operation is similarly beautiful, the arc of a precariously balanced worker’s saw echoing that of reddish logs, splayed like fingers and bobbing in blue-green water. Francisco Mora depicts a silver miner, hunched and approaching the viewer in a claustrophobic tunnel, but not alone — his companions are visible laboring in the background. Though the prints in the “Mexican People” portfolio were intended for a US audience, they nevertheless evince the TGP’s populist concerns; for a campaign promoting export products, the images here pointedly privilege the laborers, their tools and their environments over the products themselves (in much the way Rivera emphasizes the auto manufacturing process over actual cars in his Detroit Industry murals).

Natalia Rocafuerte Pocha Dream, 2021 Lithograph

Inspired by Jungian analysis, which posits that dreams are the way the unconscious communicates with the conscious mind, artist Natalia Rocafuerte set up a hotline, complete with ads featuring cheesy late-night infomercial style graphics, encouraging immigrant women from Detroit and South Texas to call in and answer a survey about their dreams. From these reports, Rocafuerte created short films interpreting the dreams, done in a chaotic, disjointed video collage technique that echoes dream logic: overlapping images, snippets of random advertisements and social media videos, computer games, songs and other pop ephemera.

Natalia Rocafuerte Dream of Emma and Tony, 2021 Lithograph

The eleven-and-a-half minute clip featured at FIA is entitled Pocha Dream, a reference to a (somewhat joking) slang term for Mexicans who’ve lost their Spanish, and perhaps their culture — who have “changed color,” like a rotting fruit (so explains the robotic voiceover that opens the video). The clip includes Dream of Emma and Tony, a short that got Rocafuerte named Best Michigan Filmmaker at 2021’s Ann Arbor Film Festival. In Emma and Tony, Rocafuerte recounts a dream encounter with her normally reclusive (and deaf and blind) grandmother. As she talks, home movies of the older woman are intercut with a face-constructing computer program from the Sims game, as if Rocafuerte’s mind was casting about trying to build a memory of her Abuela. Nostalgic TV ad jingles and graphics from news programs occasionally interrupt the story. The scene somehow segues to an elevated train, traveling first through a Chicago-esque cityscape, then into the desert of west Texas. Along for the ride are an annoying white tourist, and SnapChat denizen and self-described “ladies man” Tony Johns, who hoots and drops inane life advice. Obnoxious as Johns seems, Rocafuerte finds herself admiring his self-confidence. The desert gives way to a meadow just before the dream abruptly ends.

Aside from noting their common origins from Mexican artists, it might be a bit fraught to suggest there are common threads running between 2,000-year-old clay figurines, 78-year-old lithographs, and a Covid-era short film. Suffice to say that the artworks in each exhibit address, and dignify, the quotidian concerns of the artists and their subjects. Those concerns may be personal or political, practical or spiritual, and sometimes all of the above.

From Earth To Sky: Ancient Art of the Americas – On view now through August 25

Mexicanidad – On view now through September 8

Dream Machine Archive: Pocha Dream –On view now through July 31