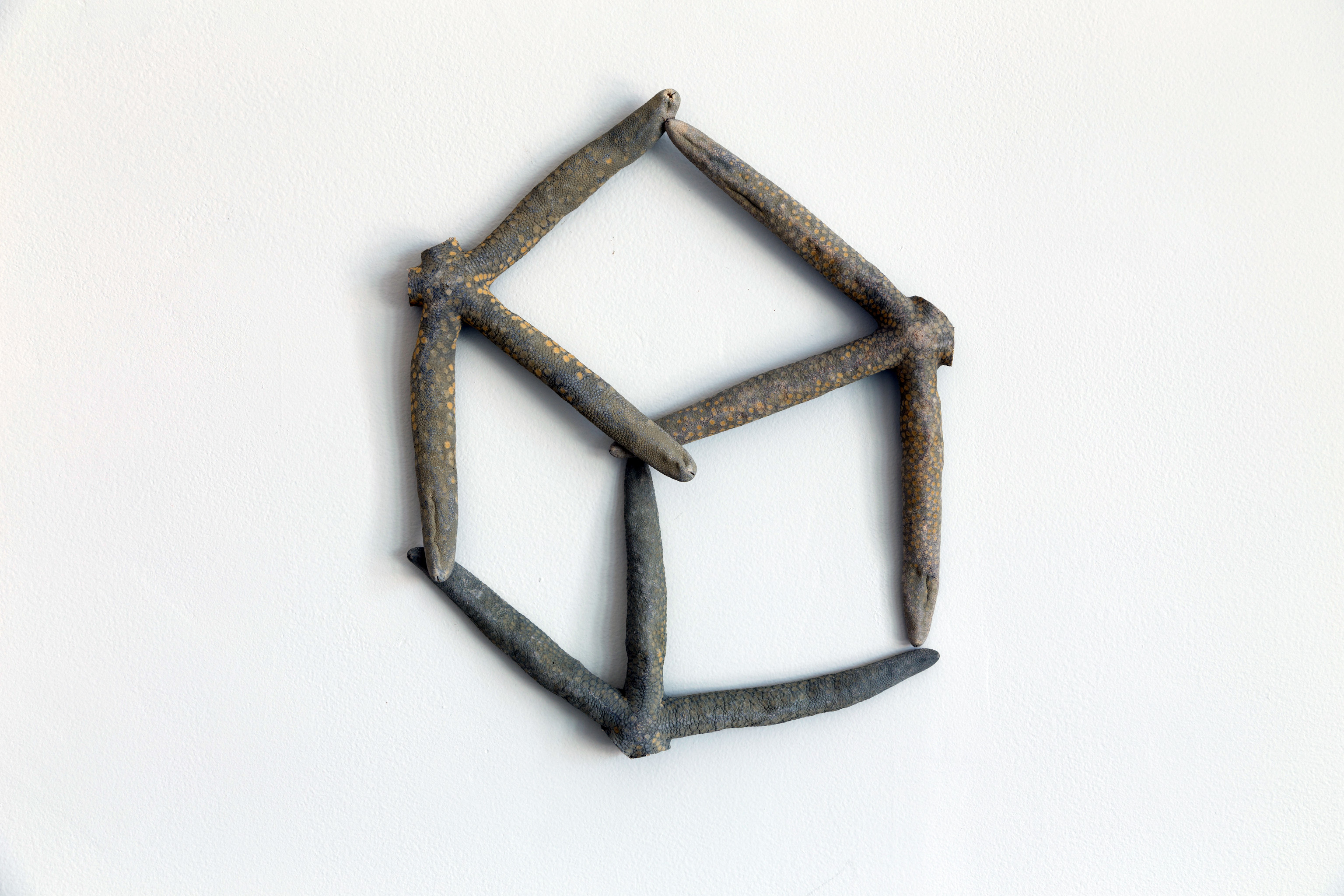

The Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center kicked off its 2018 fall season with contrasting exhibitions by Dick Goody and Anne Gilman.

Dick Goody exhibition at the BBAC main gallery, Install image. 2018

At the Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center, in the Kantgais / DeSalle Gallery, Dick Goody, Professor of Art and Chair of Oakland University’s Department of Art and Art History, serves up expressionistic painting that continues along on his path of depicting a universe of figures, landscape and still life that feel at times autobiographical. The oil on canvas works are flat, nuanced, ambiguous and reflect a somewhat consistent color palate, especially his repeated use of his selected color of red. What has left his subject matter from previous work is the direct use of words and writing passages, that in the past work would often dominate the composition. In this exhibition, The Garden City, Goody’s painting seems like a cross between early figurative work by the English artist David Hockney, and the black outlines used by the German expressionistic painter Max Beckmann as in his work Quappi in Grey, 1948. These Goody paintings are not copied from any reality, but rather are a style of painting where the artist seeks to express an emotional experience reflecting his environment: cutting the grass, reading a book, playing the piano, observing an object or having a meal.

Dick Goody, Haberman Cutting the Grass, Oil on Canvas, 54 x 36″, 2017

In the painting, Haberman Cutting the Grass, we see Goody’s persona, Haberman, cutting a small patch of grass, maybe in an English village, or an older Detroit 1920’s neighborhood, perhaps fueled by nostalgia from growing up in England. There is a real economy of form and color that accompany this figure-centered composition. With the character’s mouth open, we wonder what he is saying. Not that it matters.

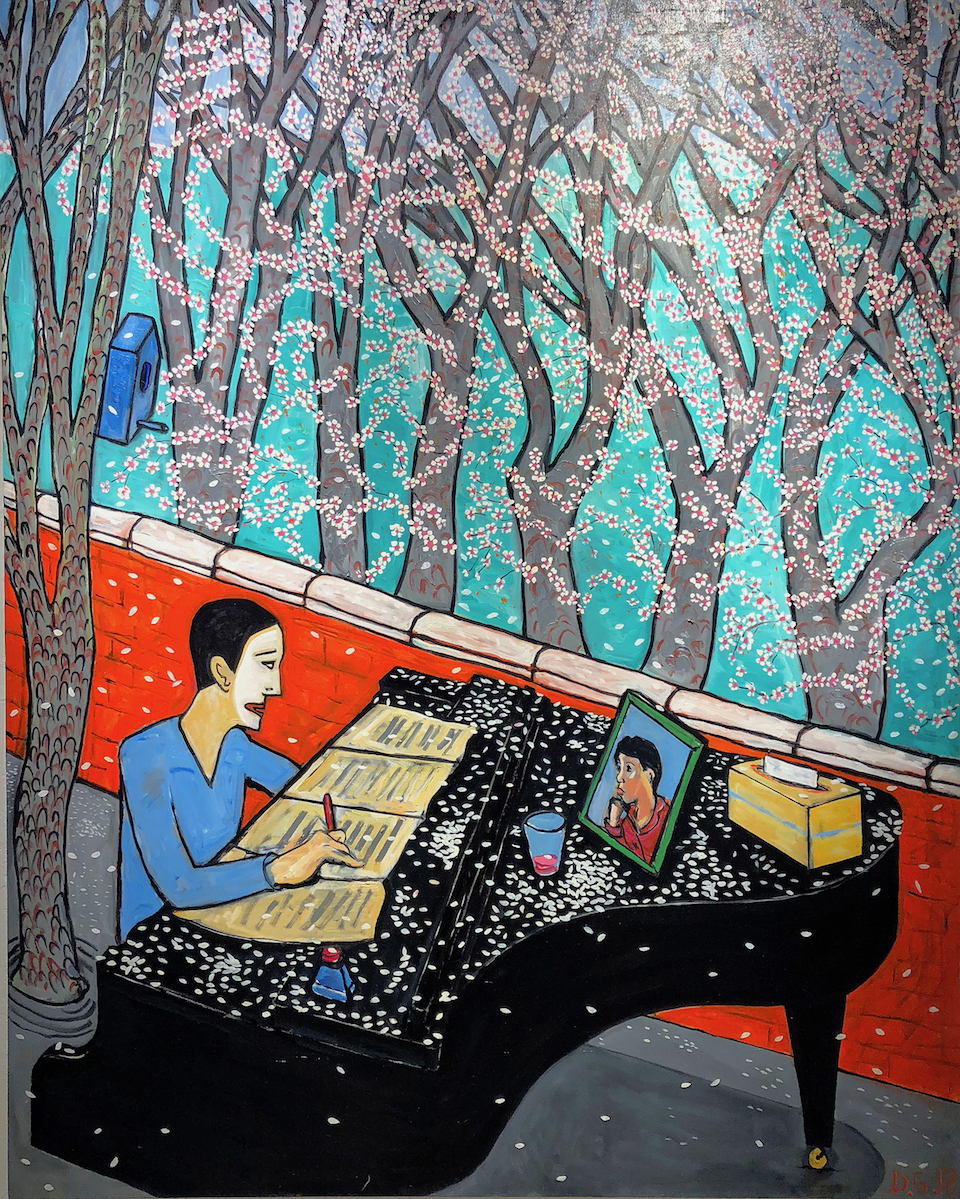

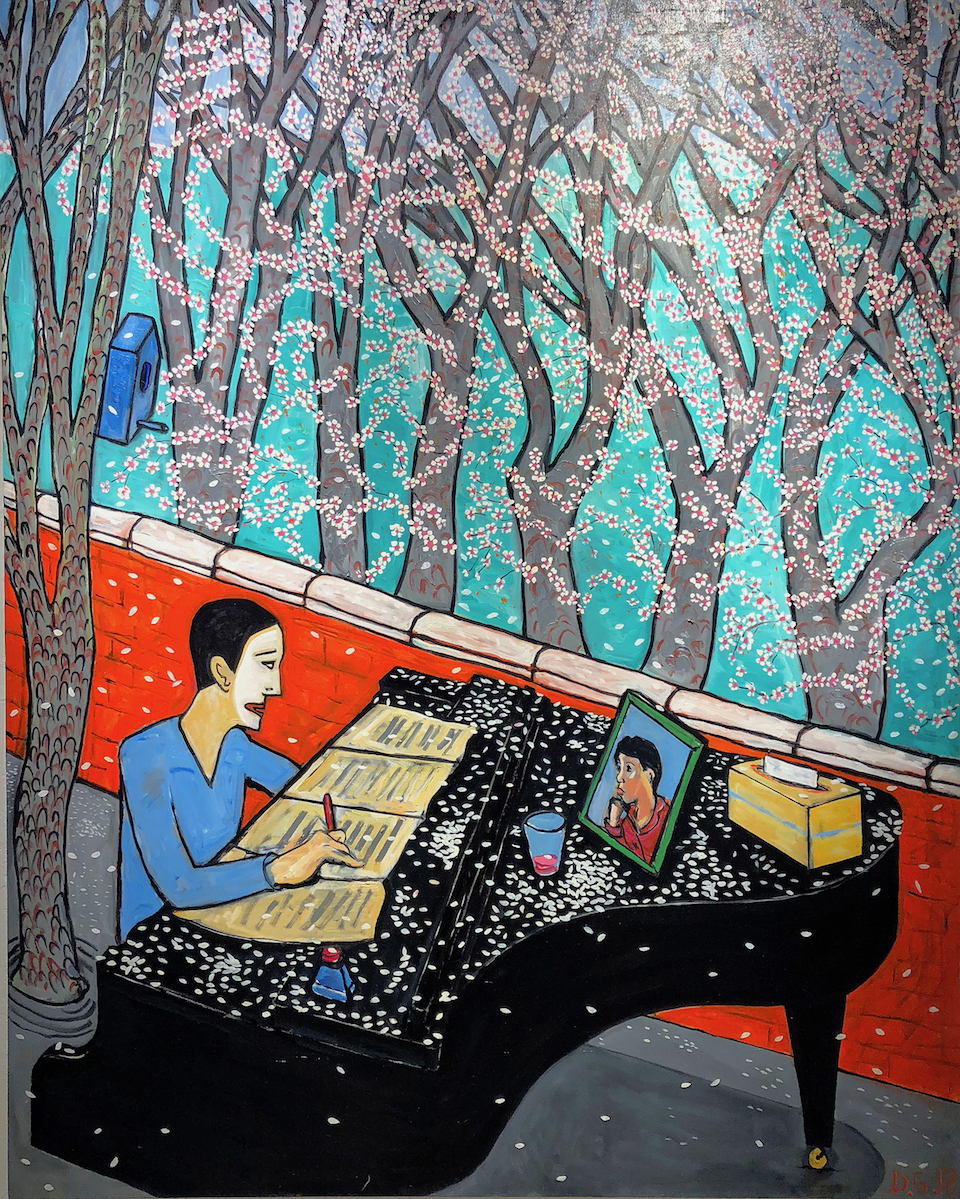

Dick Goody, Zeilwand Lieb, Oil on Canvas, 82 x 65″, 2018

Clearly, these images are figments of an imagination that is autobiographical and asks the question: Can you ever really get beyond yourself? In the work, Zeilwand Lieb, the character is sitting at the piano in a theatrical form of “white face” while spring trees shed their pedaled flowers, Goody’s figurative persona ponders a musical manuscript. He selects his objects carefully and adds a touch of serialism to this expressionistic picture. Inside or outside… or both?

I sat down with the artist and asked a few questions.

Ron Scott – How would describe your interest in painting from an earlier age onward?

Dick Goody – When I was a kid – I loved old sailing ships – like the ones Admiral Lord Nelson commanded at the Battle of Trafalgar. I spent hours and hours drawing rigging and sea battles. Out of the blue, when I was eight, I did a painting of popsicles: primary colors outlined in black – really, if you think about it, not a lot has changed – and the teacher put it on the wall. I remember it because things like that never happened.

At the art school interview, they said: “Tell us about your vision?” I had difficulty being serious about being serious. So I stared into space and said I wanted to do horses and astronauts. At the end, they said: “Ah, so you’re a history painter. “My first painting was of Clint Eastwood against this brutalist architectural background. My tutors hated it. They said: “Chill out and loosen up.” After three years of this I ended up doing simplified paintings of aeroplanes, but the moment I graduated I started doing scenario paintings again, pictures of food or people. I did a huge painting of a hunk of Stilton followed by a small roll of toilet paper picture – bought, incidentally, by an art historian, of all people.

Ron Scott – What kind of personal experiences best inform your work?

Dick Goody – All sorts of things. I mean it’s my life. Someone asked me why there’s an ironing board in one of the paintings. I live in a 1920s Tudor in Detroit and I saw this photo of David Bowie in his first house, Haddon Hall, which was a large Tudor revival in Kent, and there’s an ironing board in the living room and it made me remember how people in the UK do their ironing wherever there’s a TV. There’s a piano in several paintings and there wouldn’t be if I didn’t have one. There’s another painting of two people having dinner called Too Many New York Dinners and it’s about the whole adventure of dining out there, which after a while becomes no adventure at all, just something that’s going to eat up three exhausting hours.

Ron Scott – A few years back when we had lunch, you mentioned to me that you thought painting was “dead”? Am I right about that and has that idea undergone a change?

Dick Goody – If it was before 2006, I may have said that, but I can’t remember. It’s a stupid thing to say. Painting is immortal, isn’t it? But sometimes we go through periods when it seems to be on life support. Right now, it’s full of life. So yes, it’s changed, but it’s always changing. There’s a lot of diversity in painting right now in every sense.

Ron Scott – Do you see any relationship between your curatorial work and your painting?

Dick Goody – Don’t do both on the same day. I wouldn’t want to defuse a bomb when picking up my brushes either. In the studio, I shut everything else out. There has to be a firewall between the two things. Curating is about the macro; it’s all-encompassing. It follows protocols. There are all sorts of systems in place and multiple external reasons for one’s decisions. Painting is like getting in a car in your painting clothes without a clear idea of where you’re going – let’s just say that when I’m painting I’m not thinking about the skill and discernment it takes to organize exhibitions – I only care about the paint and the action in front of me. Truly, in the studio, on any given day, I have no idea where I’m going to end up.

Ron Scott – Could you explain more about the environments that you create in this universe of yours. ?

Dick Goody – There are not that many things: reading, playing the piano, a long evening meal, work, my house, the garden, traveling. It’s a very narrow universe, but it has to be. But the universe of one’s paintings is an immense region and full of digression, hidden pathways and side trips – and adventures, infatuations, and fixations.

Dick Goody, What are you taking about?, Oil on Canvas, 36 x 48″, 2018

As the artist explores his Garden City with its landscapes, personas, domestic norms, and objects of interest, he has created this imaginary world. The work, now void of literary statements, books, and characters from his dystopian novella, Goody has turned introspective, and I contend, nostalgic. Strong compositions, are supported with vivid color palette and black line. In the work What are you talking about?, Goody has his painting, Haberman Cutting the Grass, inside the composition and a target on his back, where he becomes the center of the universe, asking the female character, what are you talking about? They’re talking about art.

Dick Goody earned a Master of Fine Arts degree from the Slade School of Fine Art in London. He also holds a Post Graduate Certificate in Art and Design Education from Middlesex University. Goody’s own paintings have been featured in nine solo shows and over forty group exhibitions in London, New York and Detroit.

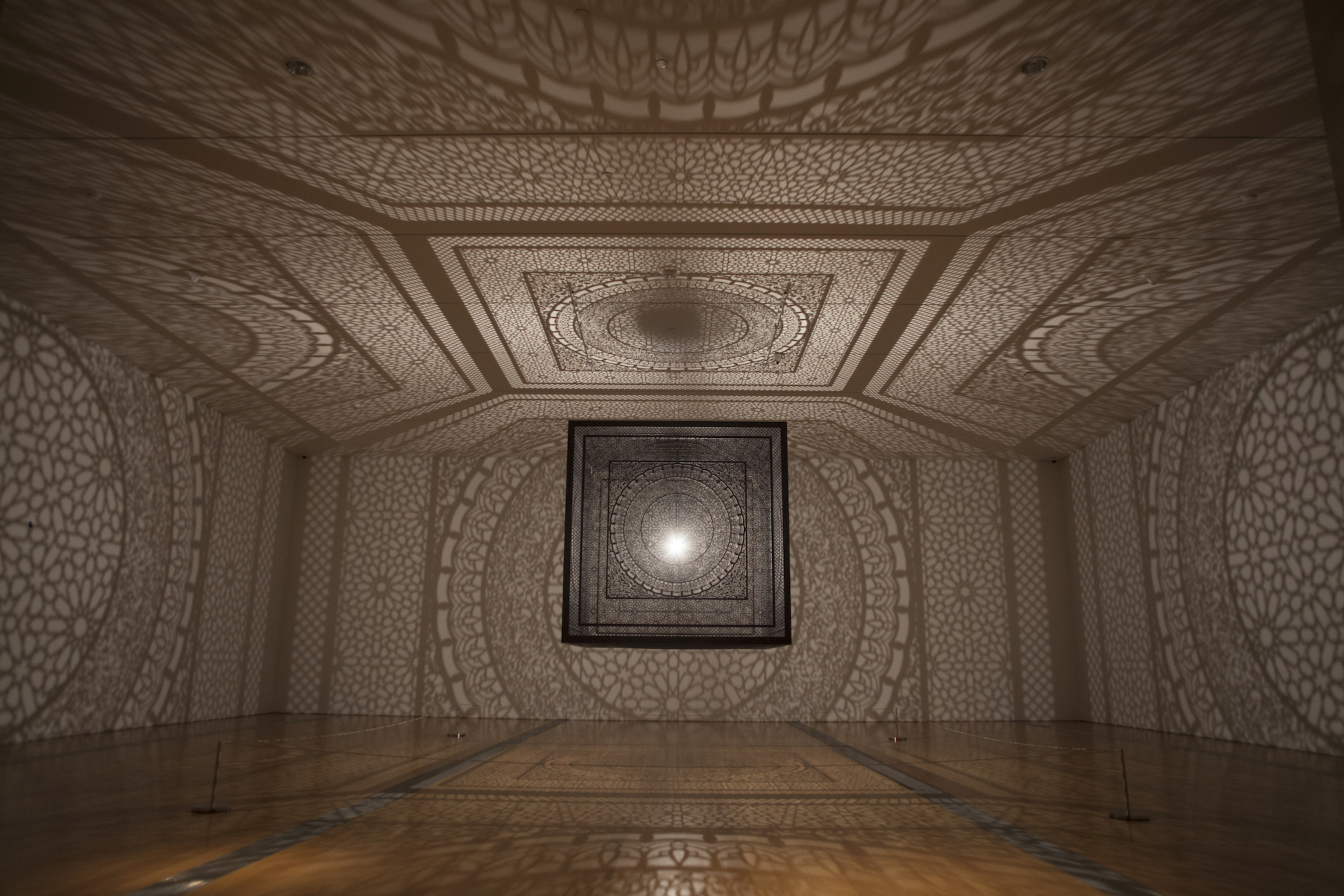

Anne Gilman – Up Close / in the Distance / Now, Conceptual Works on Paper

Anne Gilman, BBAC Robison Gallery, install image, 2018

As part of the opening season at the Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center, the Robinson Gallery hosts the work of Anne Gilman, a native of Brooklyn, NY whose work is made up of drawing and writing on large sheets of paper where she displays her thoughts and feelings combined with color patches that in some cases reflect a mood or psychological state of being. These works could be described as maps that delve into personal explorations of the artist combined with events in the outside world.

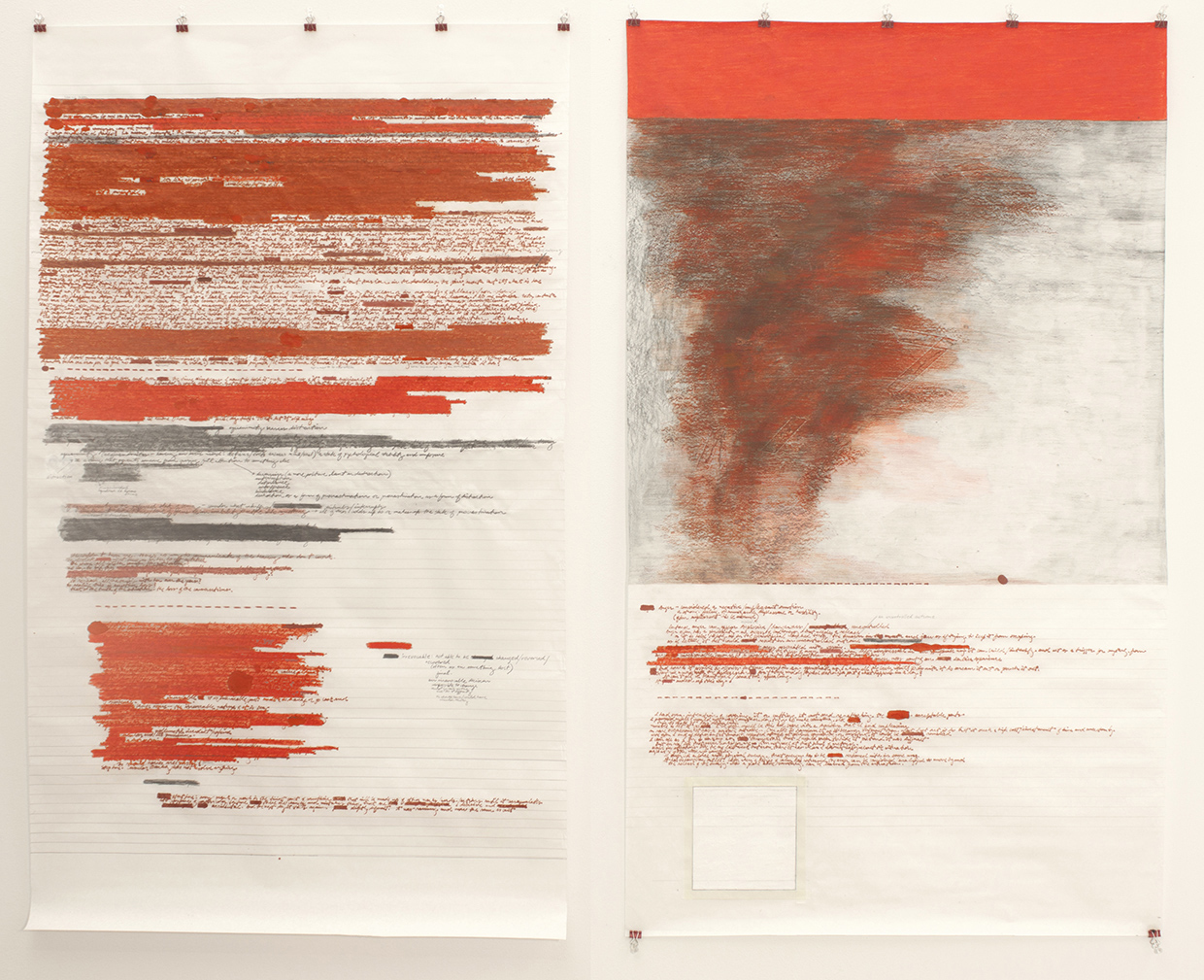

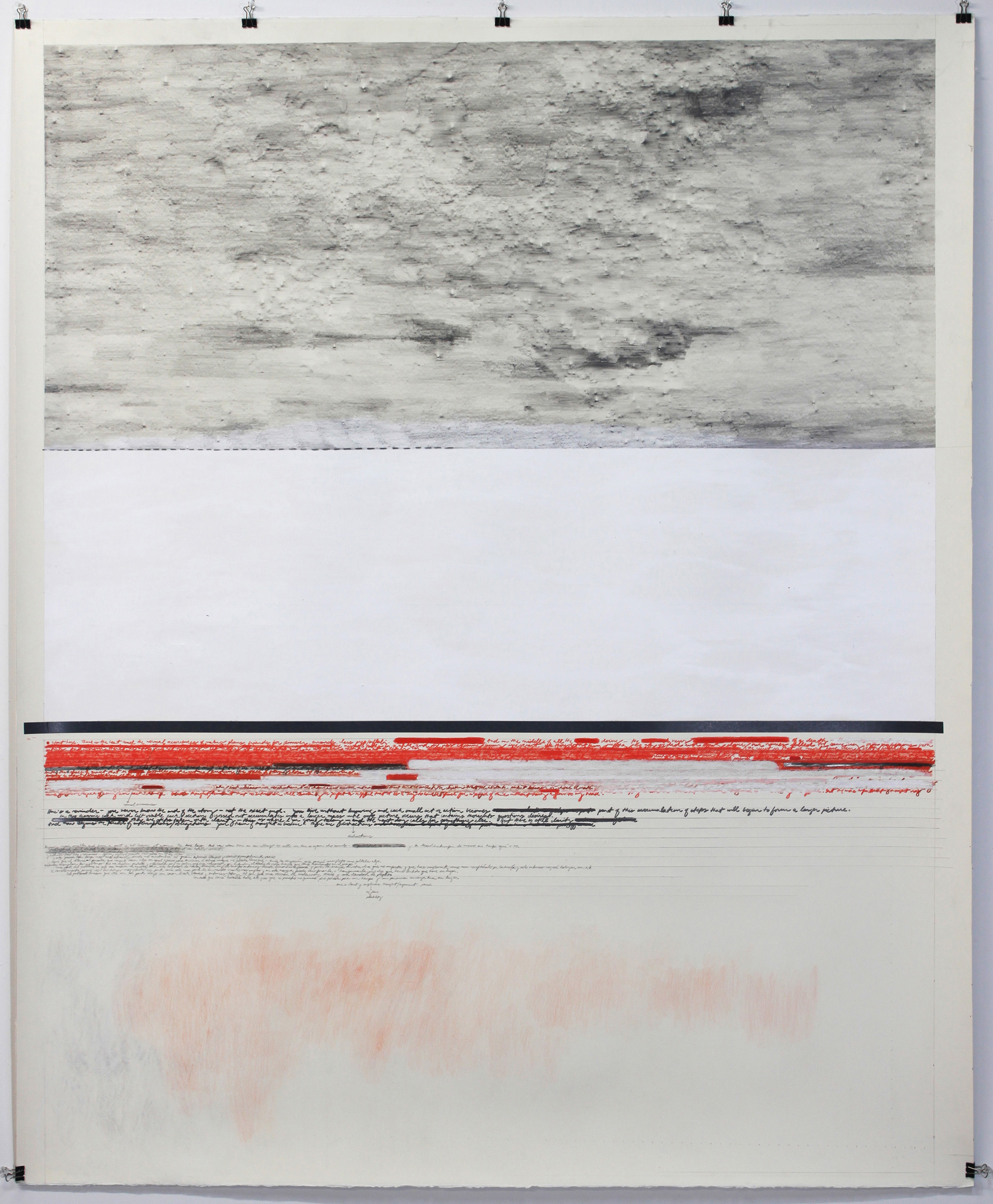

Anne Gilman, Boiling Point, Ink, pencil, on Mulberry paper, 2018

What this viewer experiences in the piece Boiling point,is a combination of literary expression, a confluence of material, and a concern for composition and color. The work on paper is often monochromatic in that there is a preference for a red theme, or blue theme that combines horizontal line work with cursive writing, intentionally not legible.

Gilman says, “I often work on paper that is larger than my body so I can sit on top of it and become immersed in its space. I rule out lines for extemporaneous writing and create confined spaces that contain layers of color, texture and tape. I use my own response to personal, political, and social concerns as the starting point for creating a mapping of information, thought, and emotion. Keywords and phrases reference ideas that emerge as I work while large expanses of texture reference an inscrutable landscape or atmosphere that I create as a safe or calm space.”

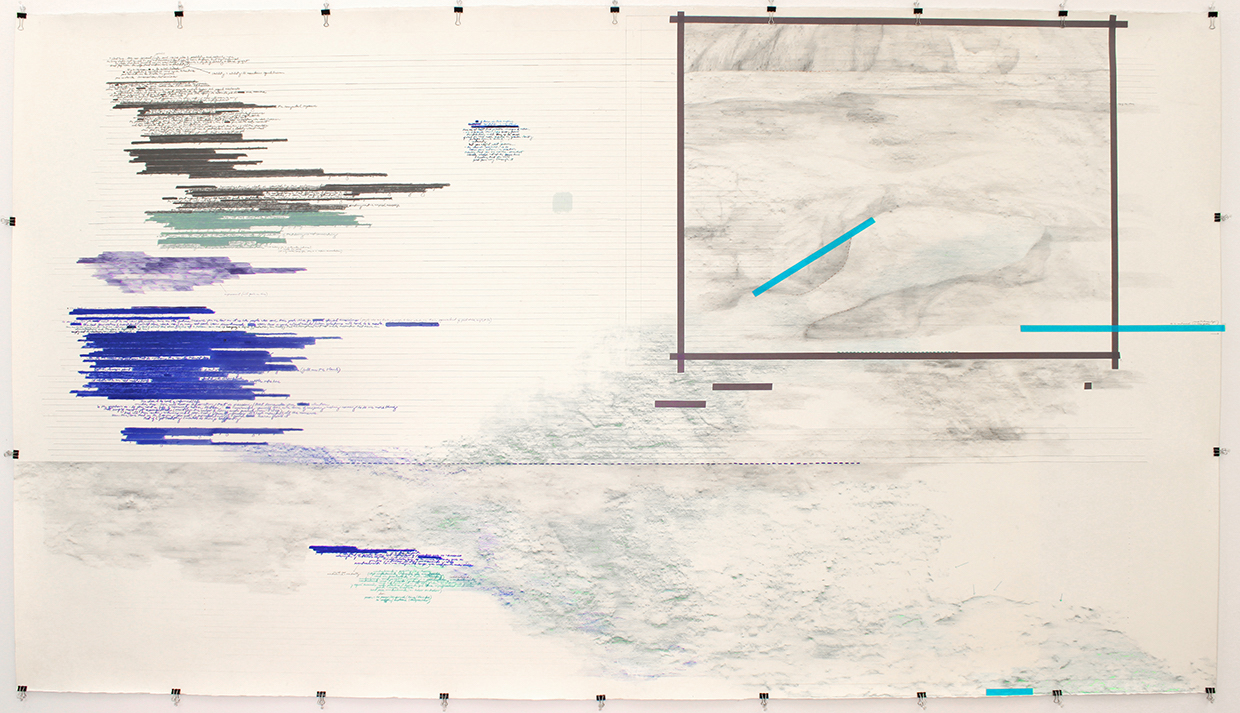

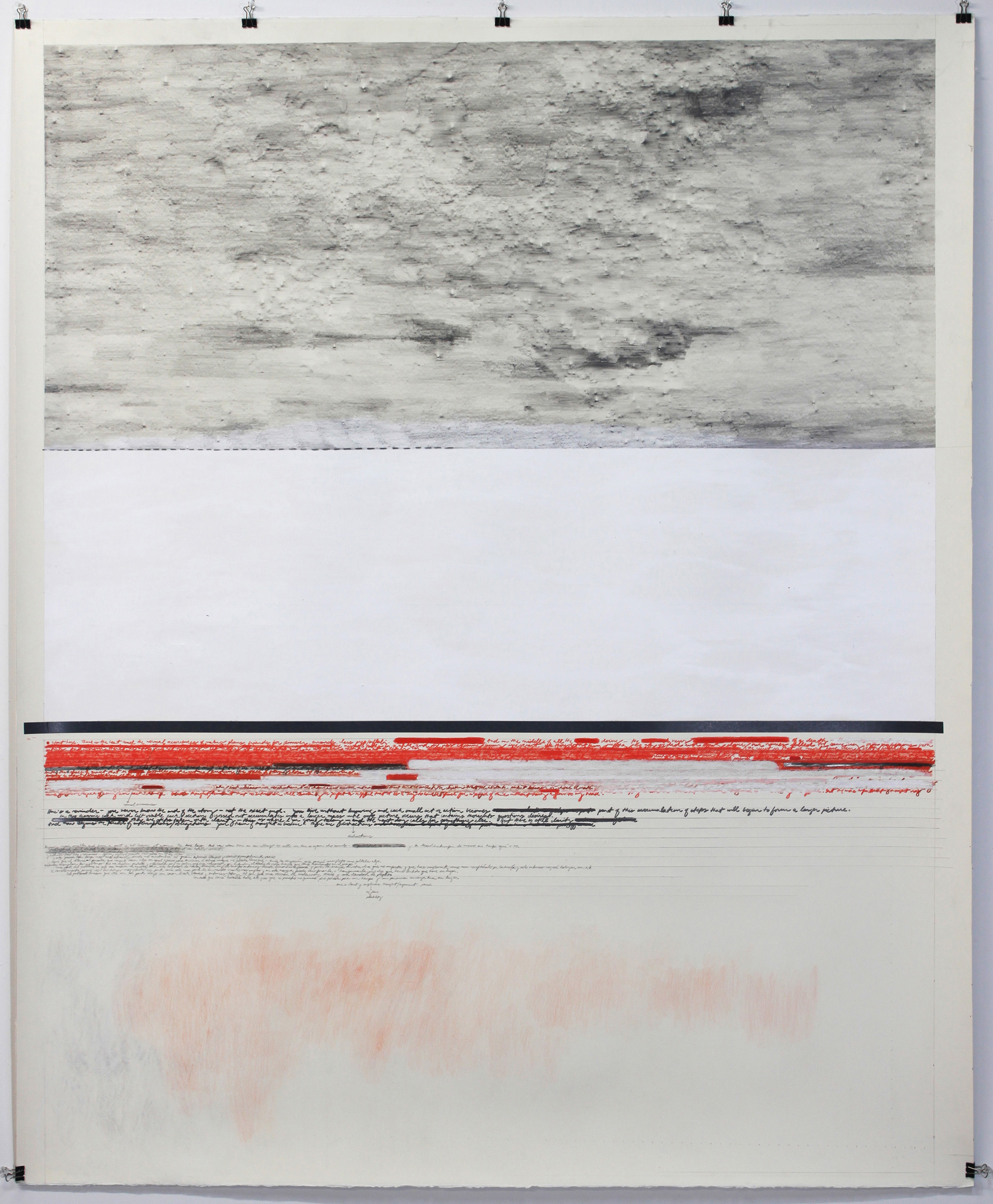

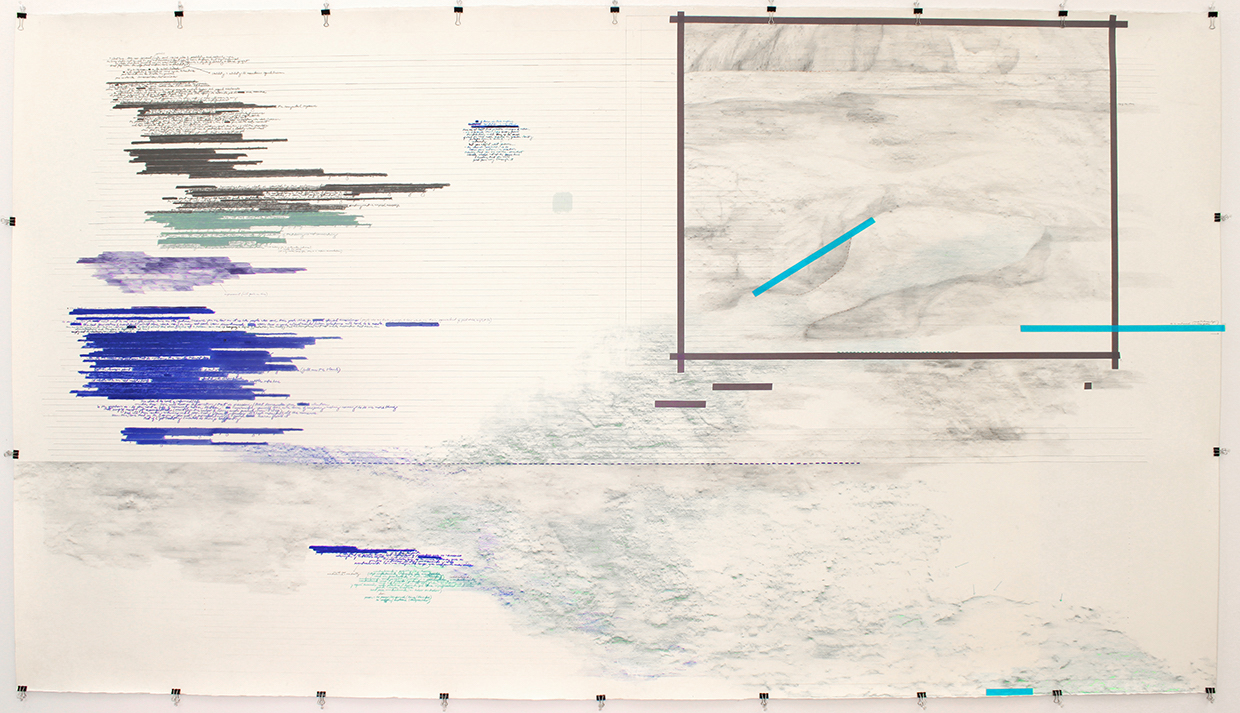

Anne Gilman, You might wait forever, Pencil, graphite, ink, BIC pen, tape on paper, 2018

Often her work is triggered by an event, be it political, social or personal, where she makes her selection of color and writing, where the mapping of information is secondary to the layout of space, color and composition. I refer to the work as conceptual in the open, meaning work where the concept or idea behind the work is more important that the finished art object, but this work could be easily described as drawing / installation. Her concerns as an artist address her concerns as a person that seems to be launched based on a psychological state of being. What is added to this exhibition alongside each work is a passage where the artist articulates background information that takes on an educational component designed to inform the work. Here is an example of what accompanies this work of art, You Might Wait Forever.

“This drawing was made after a protracted illness, so much of the text is a referencing to a reorganizing of priorities.”

An excerpt from Gilman’s extemporaneous writing: “Thinking about the degree of calm or letting go I had when I was sick, the paradox of finding some strange peace or knowledge that there was no fighting the state I was in. I was able to finally enter a non-doing state, a place where I gave into each moment and had complete clarity of what my limitations were. When you are that sick, there’s no more pushing and thinking of all the “shoulds.” When you are that sick, each moment has a particular kind of clarity about what is needed or not needed. Maintaining that clarity as you get well, that is the hard part.”

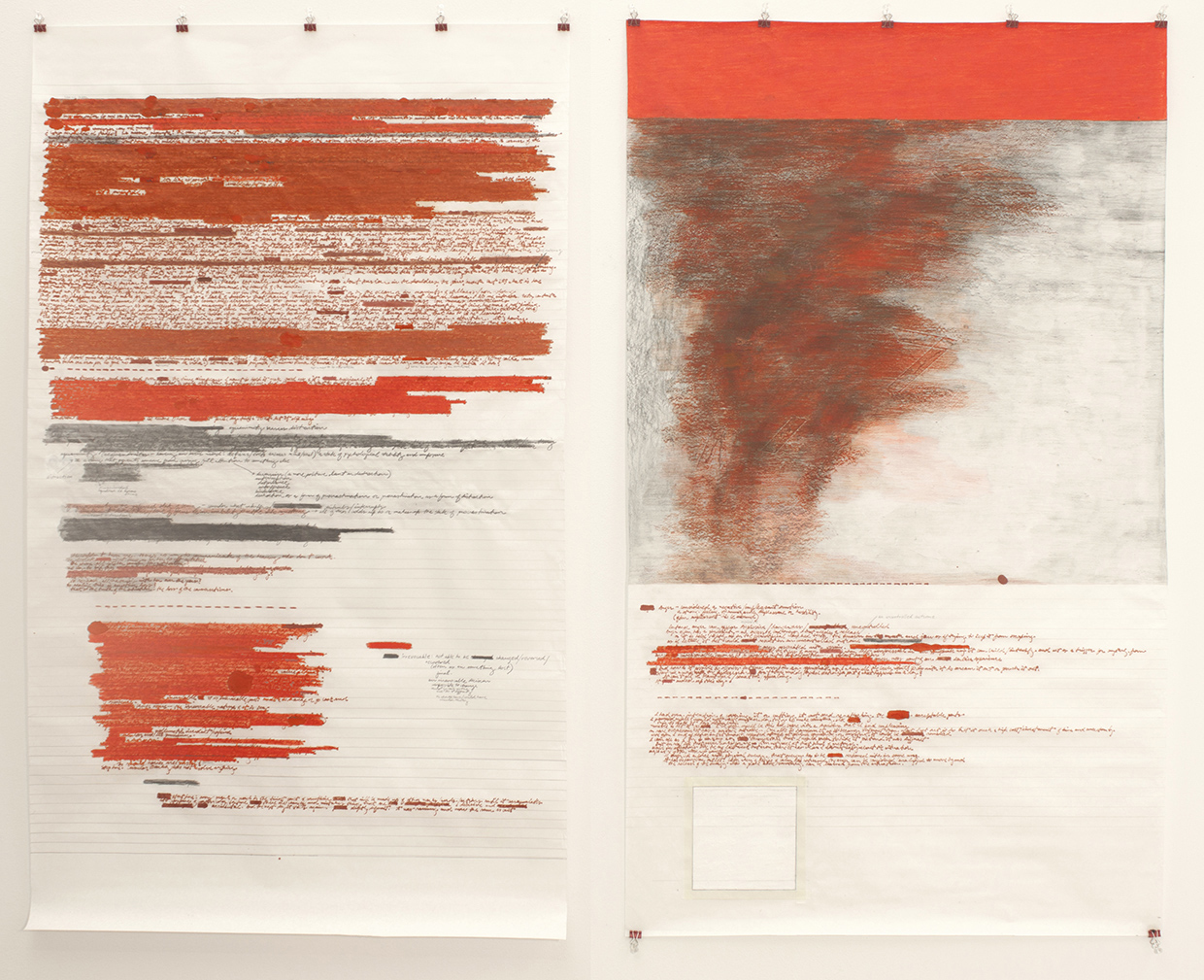

Anne Gilman, The Place of possibility, Pencil, paint, tape on paper, 2016

More abstract than others, Gilman”s The place of possibility, conveys as a reminder that you never know the end of a story. More open space, perforated line, less color, and various text that addresses the steps taken to achieve clarity, perhaps at the center of the piece.

Anne Gilman earned her BFA/Painting, State University of New York at New Paltz and MFA/Drawing and Painting from Brooklyn College, NYC. She teaches in the graduate and undergraduate programs at Pratt Institute, NYC.

Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center current exhibitions run through October 11, 2018.