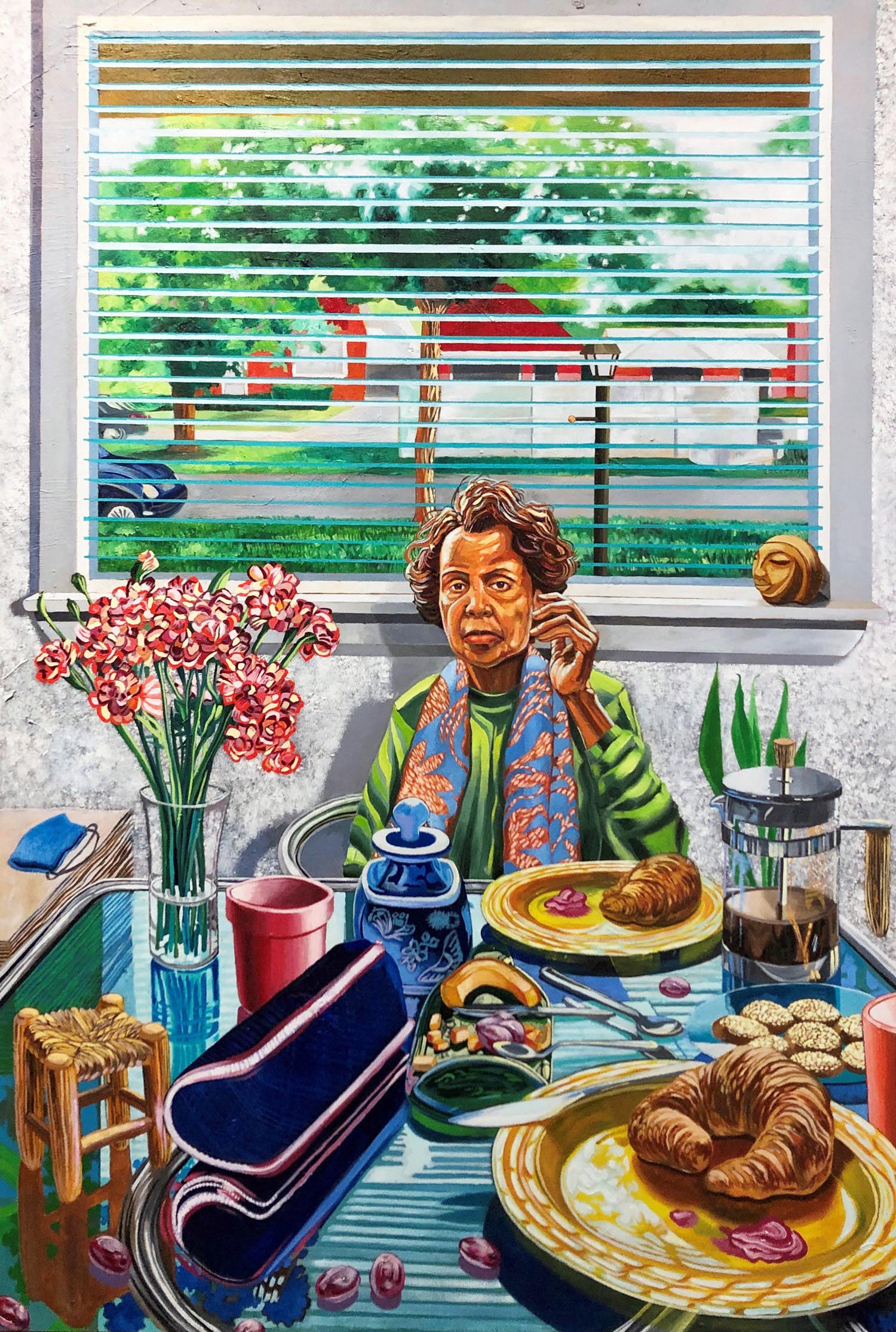

InterStates of Mind: Rewriting the Map of the United States in the Age of the Automobile installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2020. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography.

In 1928, Ford Motor Company acquired 2.5 million acres of forest in the middle of the Brazilian Amazon with the intent of supplying the company’s Michigan factories with a reliable supply of cheap rubber. Here it erected Fordlandia, a pop-up town populated by locals who, coaxed by competitive wages, worked in the employ of Ford Motors. Ford aggressively pushed American culture onto the workers, mandating, among other things, required poetry readings (in English), community sing-alongs, and American cuisine. In 1930, the workers revolted, and the Brazilian army had to restore order. The endeavor was a failure. The region wasn’t sufficiently conducive to growing rubber trees, and by 1934, the project was abandoned; however, Fordlandia’s buildings still stand, and the town attained immortality as a major inspiration for Aldous Huxley’s dystopian Brave New World. Fordlandia is just one of many examples of the automotive industry’s influence on culture presented in the MSU Broad’s excellent exhibition InterStates of Mind: Rewriting the Map of the United States in the Age of the Automobile.

This large exhibition fills the entirety of the Broad’s second floor gallery suite with a multimedia selection of art and ephemera largely (though not entirely) selected from its own collection. While it sometimes addresses the automobile industry in broad strokes, the exhibition also addresses how the automotive industry shaped Lansing in particular. InterStates of Mind gives special attention to some of the economic, environmental, and social problems exacerbated—if not always directly caused—by the automotive industry.

InterStates opens with a trilogy of early, iconic films which emphatically proclaimed an unfettered optimism of the automobile (and in technology in general) to realize an earthly American utopia. In 1939, for the New York World’s Fair, General Motors constructed an impressively large animated diorama of a city of the future, at the heart of which was the automotive industry and the highway system. The 23 minute film Futurama slowly pans through this sprawling model (designed by GM’s Norman Bel Geddes) as a narrator envisions a future in which science, technology, and the highway system are harnessed to create an ideal society. Though many of the film’s predictions indeed came true, its flamboyant optimism in a technology-driven utopia certainly rings hollow in retrospect.

Master Hands, a film also produced by General Motors, artfully walks the viewer through the manufacturing process of a 1936 Chevrolet. Underscored by a triumphant, Wagneresque soundtrack composed by Samuel Benavie and performed by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, the film’s visuals really are aesthetically beautiful, and the music engages with action on the assembly line in a perfectly coordinated dance. Master Hands showcases the undeniable ingenuity behind the assembly process.

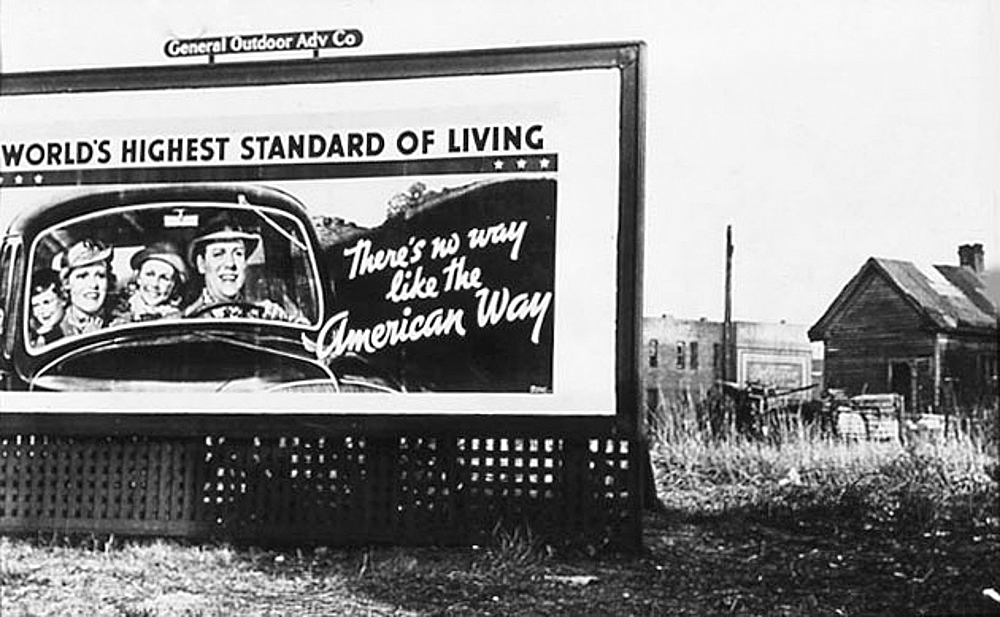

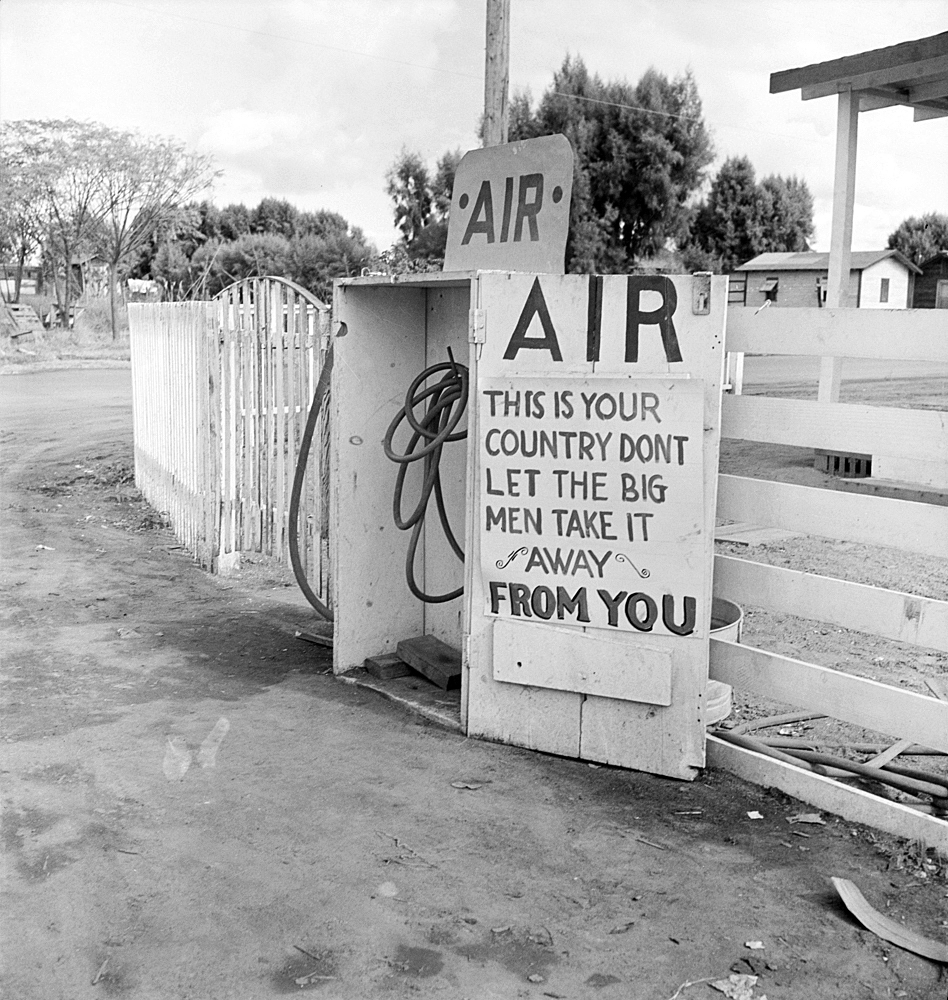

As a foil to the optimism of these films, InterStates also presents an ensemble of the socially poignant photographs of Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and other photographers whose work documented the lives of those worst hit by the Great Depression. “There’s no way like the American way,” a billboard loudly proclaims in a photograph by Arthur Rothstein, though the blighted buildings in the background brutally undercut this cheerful sentiment. While some of these photographs don’t directly reference the automobile itself, they collectively push against the utopic, concurrent visions of Futurama.

Arthur Rothstein, Sign, Birmingham, Alabama, 1937, printed 1987. Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, Michigan State University, purchase

Dorothea Lange, Gas station. Kern County, California, 1939, printed 1987. Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, Michigan State University, purchase.

This exhibit gives prominence to an ensemble of eight large photographs by Brazilian artist Clarissa Tossin, whose conceptual project When Two Places Look Alike addresses the overtly colonialist nature of Fordlandia. Many of the American-style homes built for the workers in Fordlandia still stand, and Tossin’s photographs wittily draw visual parallels between the architecture of Fordlandia’s homes with those of Alberta, Michigan, also a company town established by Ford in the 1930s.

Clarissa Tossin, When two places look alike, 2012. Courtesy the artist, Luisa Strina Gallery São Paulo, and Commonwealth Council, Los Angeles.

Given Lansing’s prominence in the automotive industry, it seems fitting that this show localizes much of its content. A generous portion of the exhibit explores the social impact of I-496, the expressway which serves as a main artery Eastward and Westward through Lansing, and the construction of which displaced a mostly African-American population from their homes. A massive enlargement of an aerial photograph shows a stretch of these houses prior to the construction of the expressway, hinting at the many lives that it would seriously interrupt.

While much of this show examines the automobile’s influence through a jaundiced eye, it certainly refrains from being drearily pessimistic. There’s a whole ensemble of photographs highlighting the phenomena of the roadside attraction. And some works celebrate the visual potential of the materiality of the automobile itself, such as Chakaia Booker’s rubber sculptures that playfully flaunt the aesthetic potential of used tires, which she manages to cut, sculpt, twist, and manipulate into forms that look almost organic.

InterStates of mind offers a considered and thoughtful re-assessment of the automotive industry’s impact on society. Though this exhibit is certainly informative (expect to find yourself reading your way through large parts of this exhibit), it’s also visually rewarding, offering visitors a veritable cornucopia of works which snugly make the most of the Broad’s exhibition space. While these works certainly aren’t disparaging of the automobile’s influence on culture, they collectively approach the subject with an honest ambivalence, and the early 20th Century visions and promises of a technology-driven American utopia, in retrospect, ultimately seem to ring hollow.

InterStates of Mind: Rewriting the Map of the United States in the Age of the Automobile installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2020. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography.