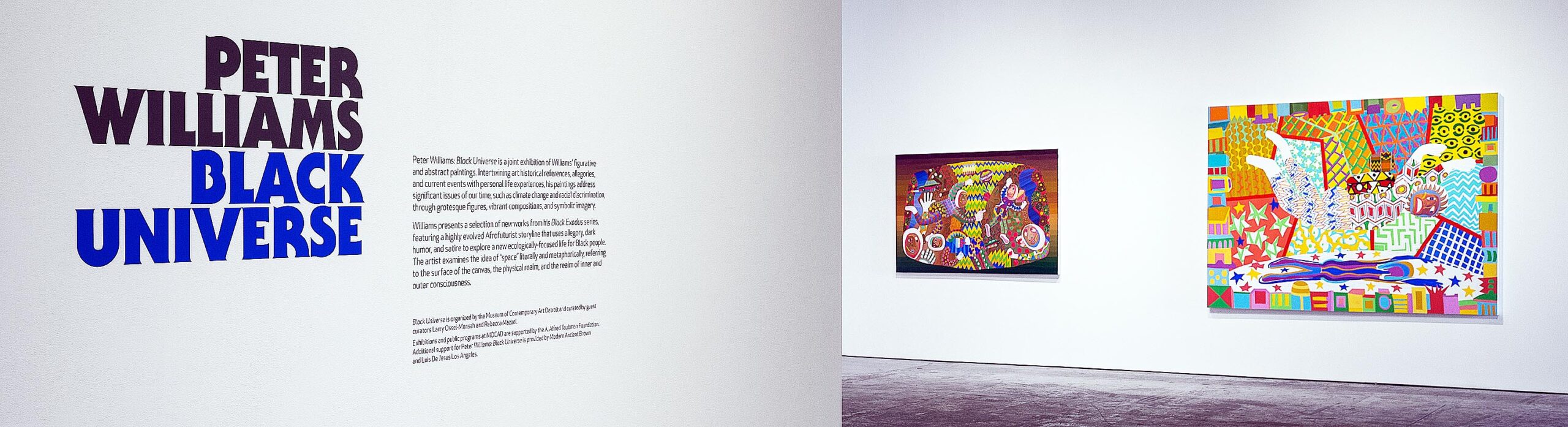

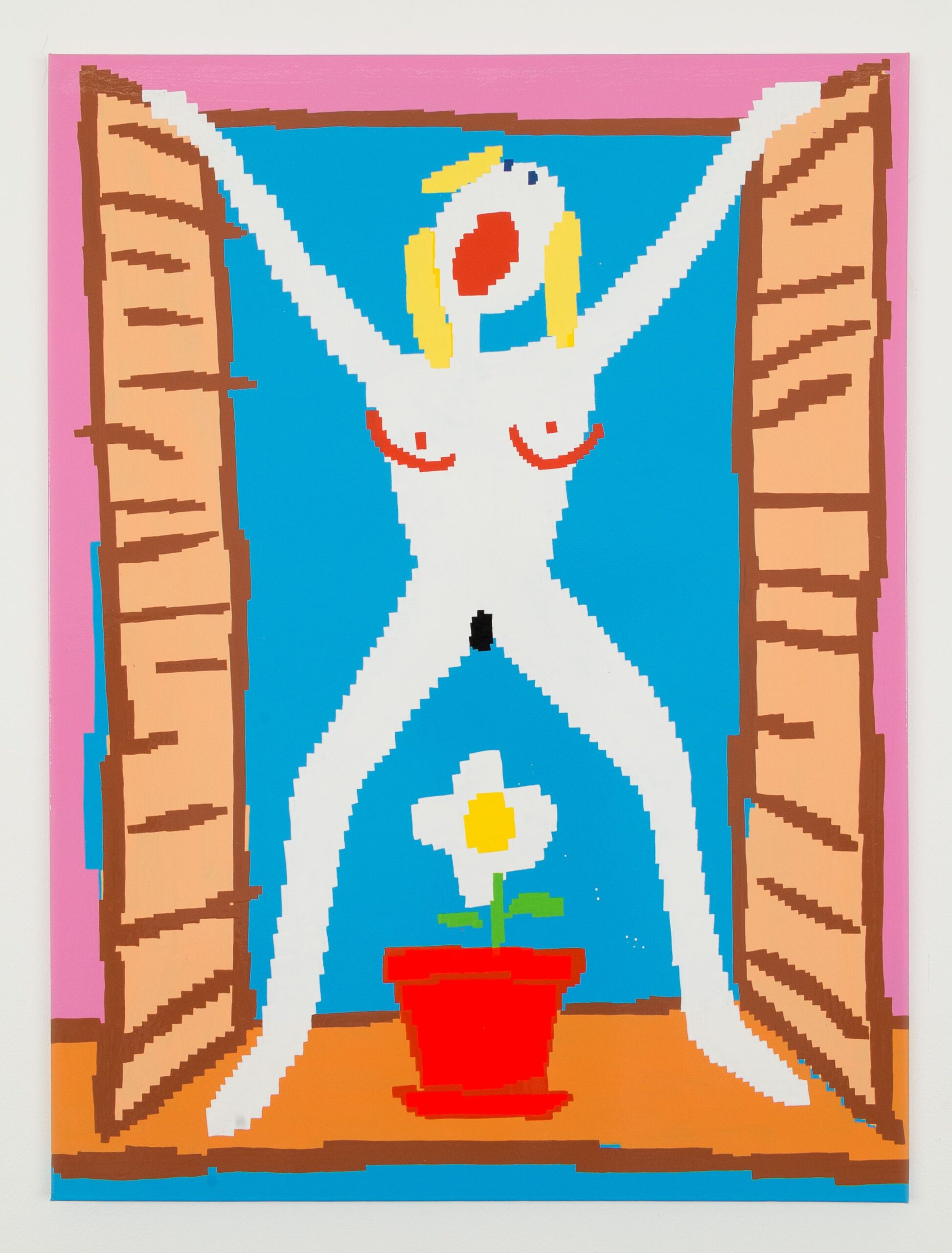

Sabrina Nelson, They Go in Threes, installation detail, mixed media and drawings.

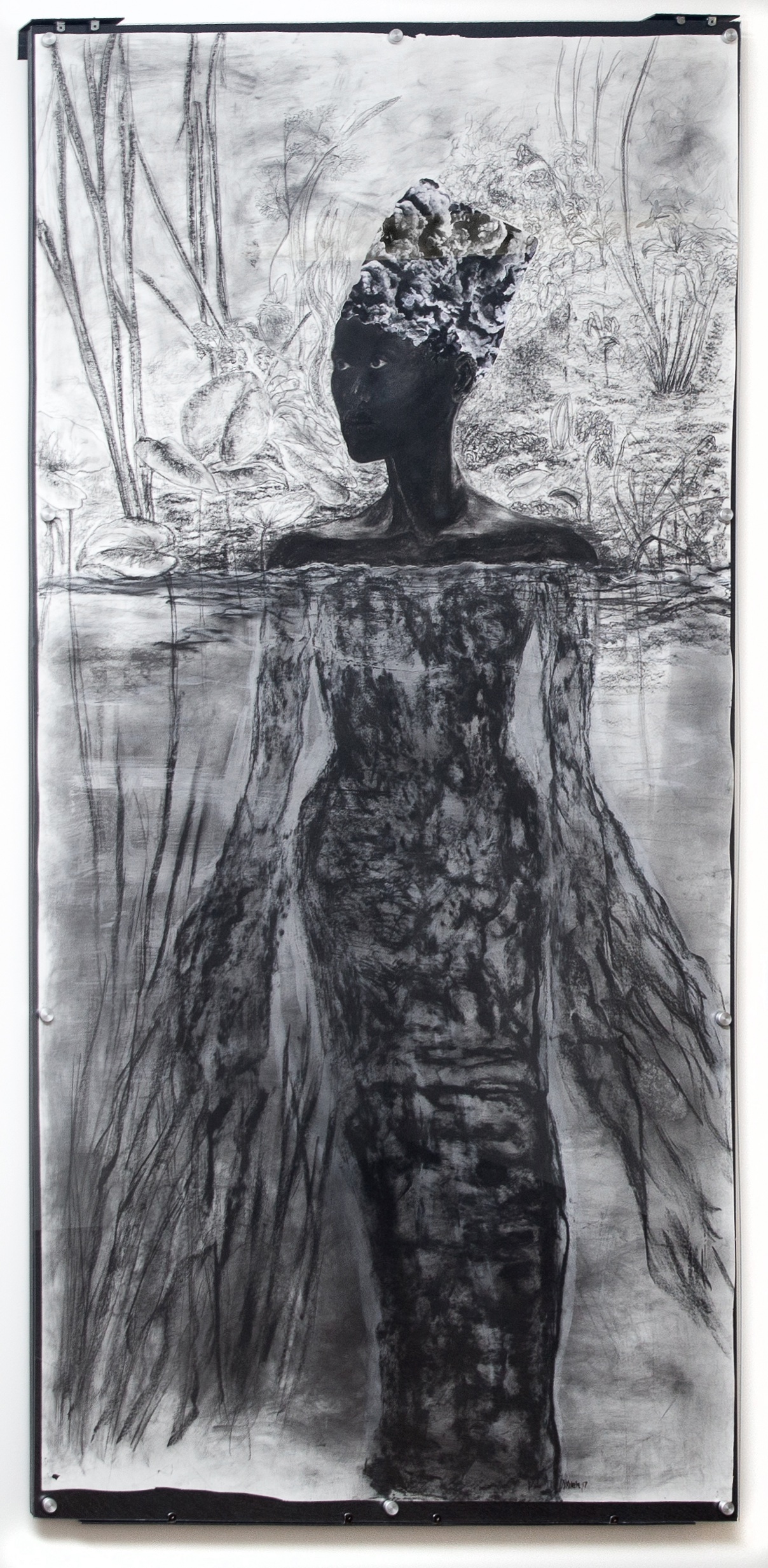

Sabrina Nelson, Detroit artist, educator and activist, has chosen the totemic blackbird as the animating metaphor for her exhibit Blackbird & Paloma Negra: The Mothers, on view now at Galerie Camille in Detroit, until October 3. Through drawing and installation with both constructed and found objects, she explores the psychic territory between private grief and public mourning felt by mothers of Black children lost to racial violence.

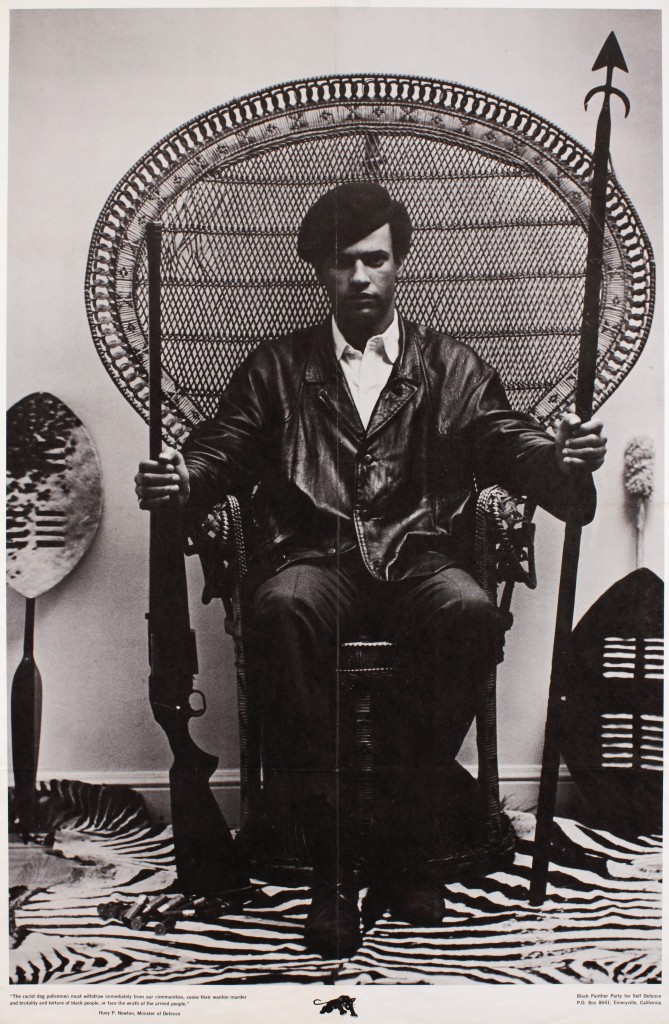

Nelson was born during the Detroit Rebellion of the 60’s, descended from a long line of strong Detroit women who she credits with galvanizing her spirit early on. In a recent article for detroitlover.net, she describes her female forbears as “three generations of remarkable, independent women who each had her own way of being… My mother was probably the most rebellious in the house. She was young, had an afro and this attitude like, ‘I ain’t doing none of that stuff y’all did — this is the new deal.’ She was down with the Black Panthers and was fighting for what she felt was right at the time. There was some serious rebellion going on when I was in her belly, so I’m sure there’s a part of that energy in me.”

True to the spirit of the matriarchs in her family, Nelson has found her own way of being and means of expression as an artist. She recognizes the emotional dissonance between the lonely, visceral sorrow a mother feels at the loss of her child and the public rhetoric that surrounds the Black Lives Matter movement. She honors this more personal sorrow with a series of artworks that are poignant, elegiac and at times seem poised to disintegrate into their broken and damaged constituent parts. In her statement she writes, ”We live in a hash-tag era, where Black and Brown bodies are brutally murdered and swiftly turned into hash-tag symbols on social media; where often the focus of how they were killed is sensationalized and who they were as valued beings in their communities is ignored.”

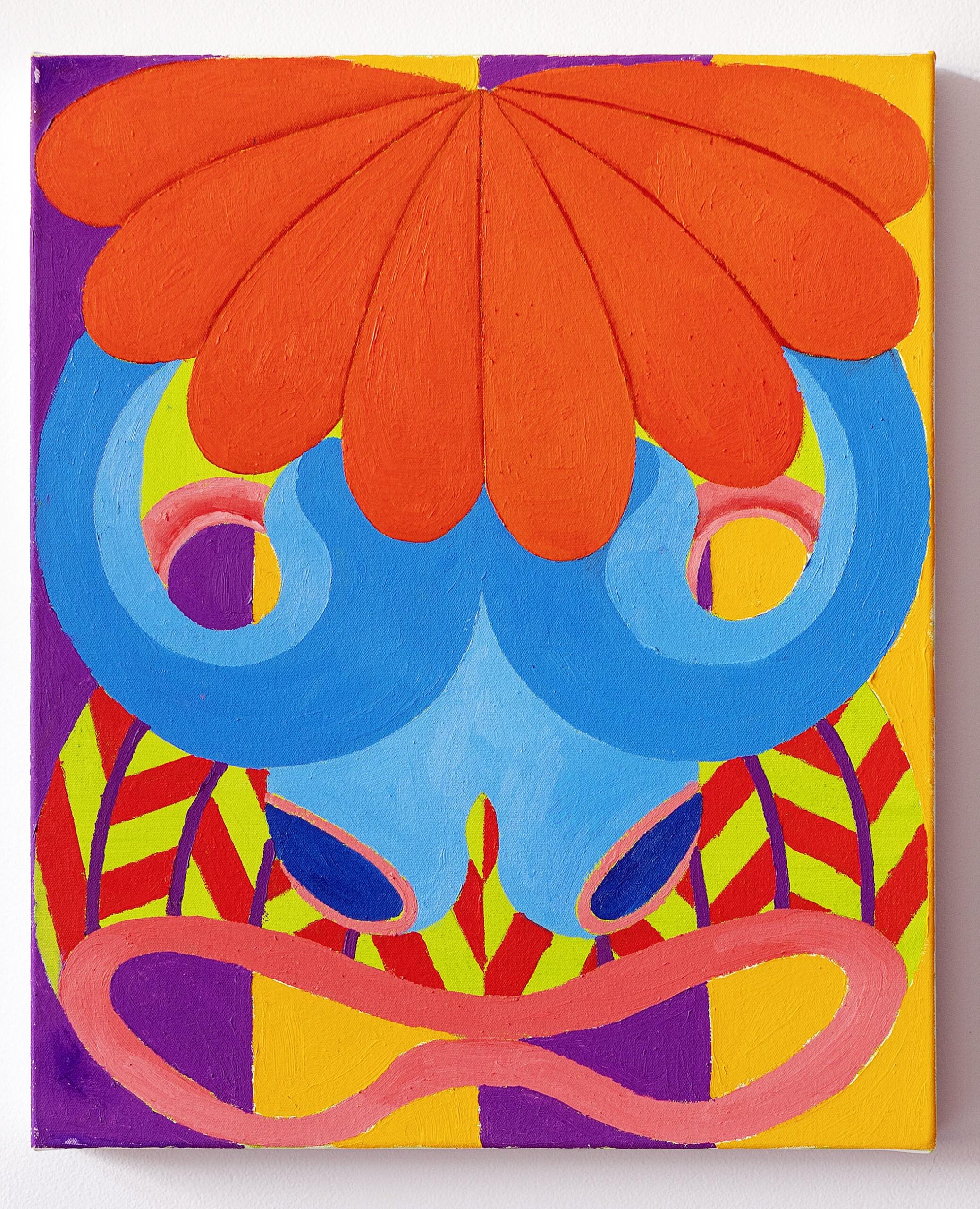

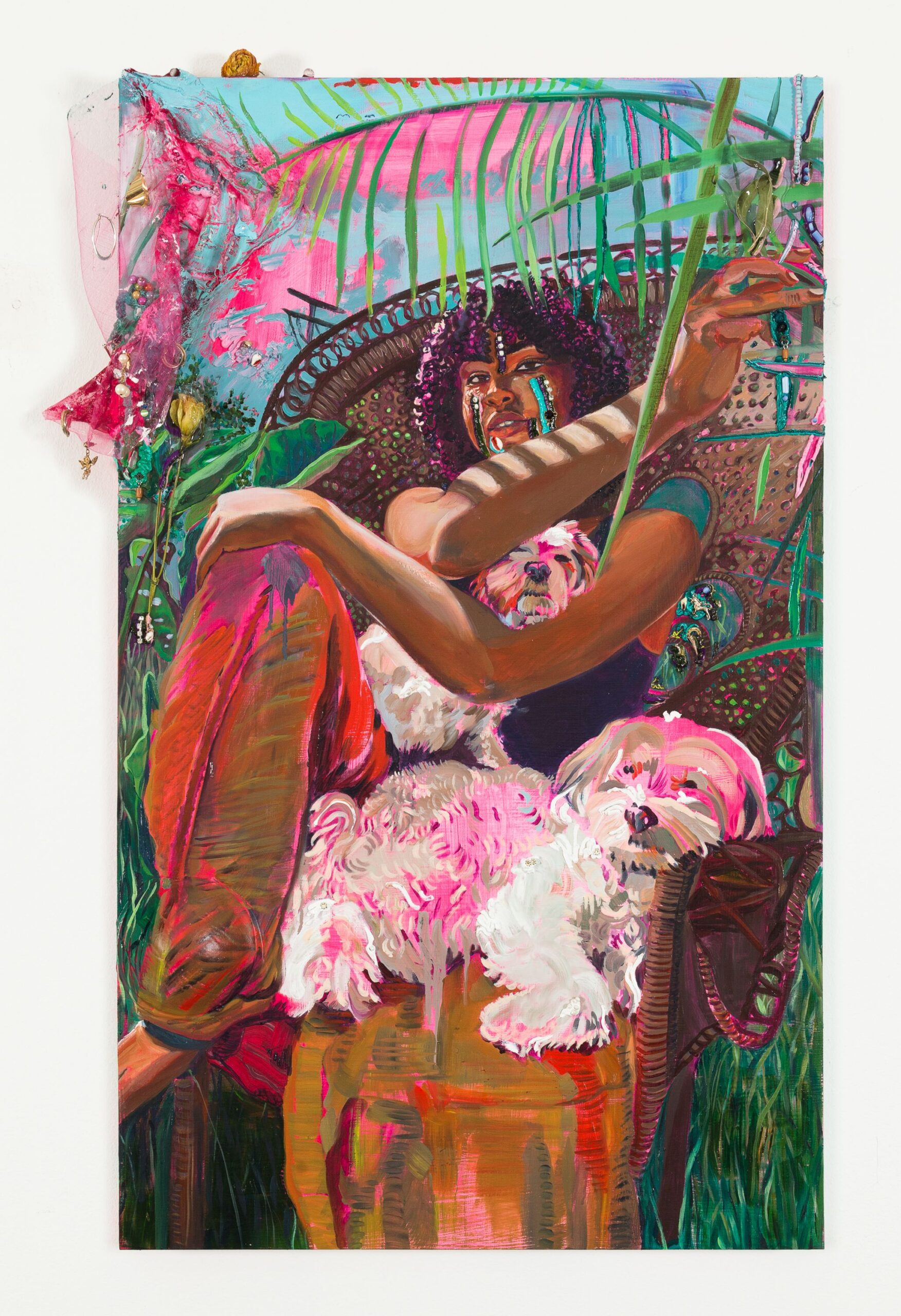

Sabrina Nelson, The First Home/ Grace 3, hanging sculpture, mixed media, size variable.

Three fragile tissue and tulle dresses hang from the ceiling in the main gallery of Galerie Camille, threatening to dissolve at the exhalation of a sigh. The dresses provide a surround for sooty and slightly deformed birdcages, their womblike forms evocatively referencing both the absence of the child and the remaining husk of the inconsolable mother. These three artworks represent the emotional core of the show and seemed, to me, to be the most direct and moving expression of her theme.

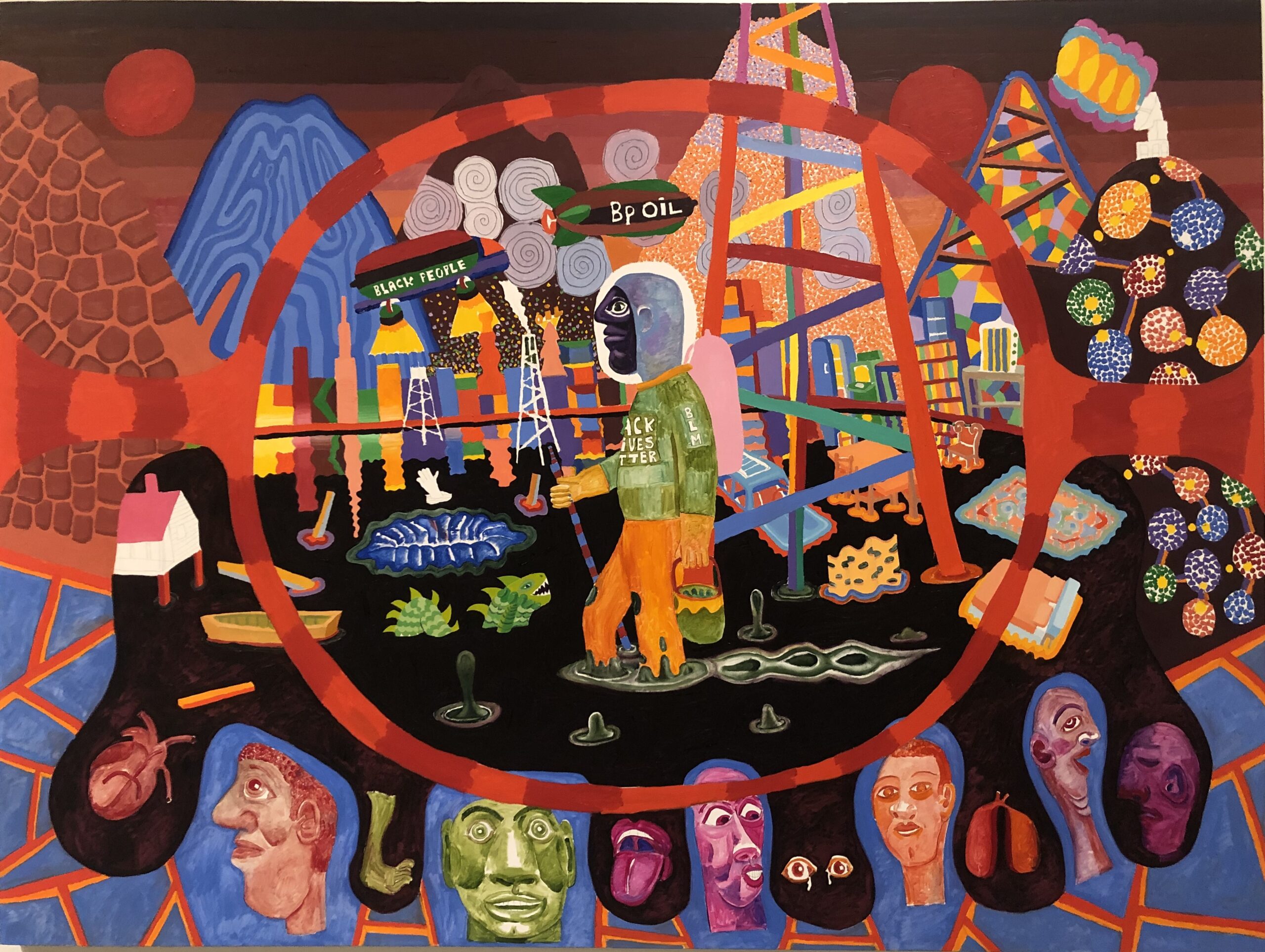

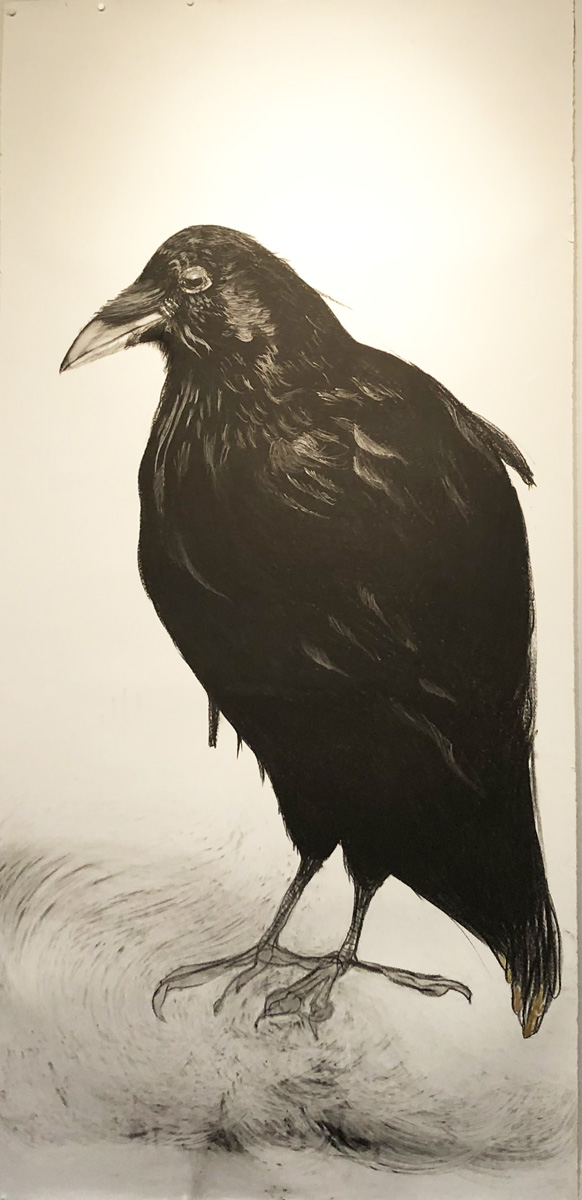

The charcoal and acrylic drawing of a monumental blackbird entitled Raven: Attempted Conspiracy, occupies a central position in the main gallery, gazing quizzically at gallery visitors as they enter. Its intent is mysterious, its cunning obvious. Her choice of the blackbird as a visual metaphor throughout Blackbird and Paloma Negra: The Mothers is both potent and equivocal and allows for multi-layered interpretations. The corvid’s complex associations across a variety of world cultures resonate throughout the collective consciousness, freeing Nelson to play at the shadowy margins. She skates metaphorically along the borders of confinement and flight, freedom, death and the afterlife, embracing the poetic ambiguity of the blackbird. She says of the species, “Our body and our nesting always tell the truth. A group of black crows is called “a murder of crows” and a grouping of ravens is called “a conspiracy of ravens” or “an unkindness of ravens”. These poetic names were given to these corvid creatures during the 15th century.”

Sabrina Nelson, Raven: Attempted Conspiracy, charcoal and acrylic on paper, 50” x 93”

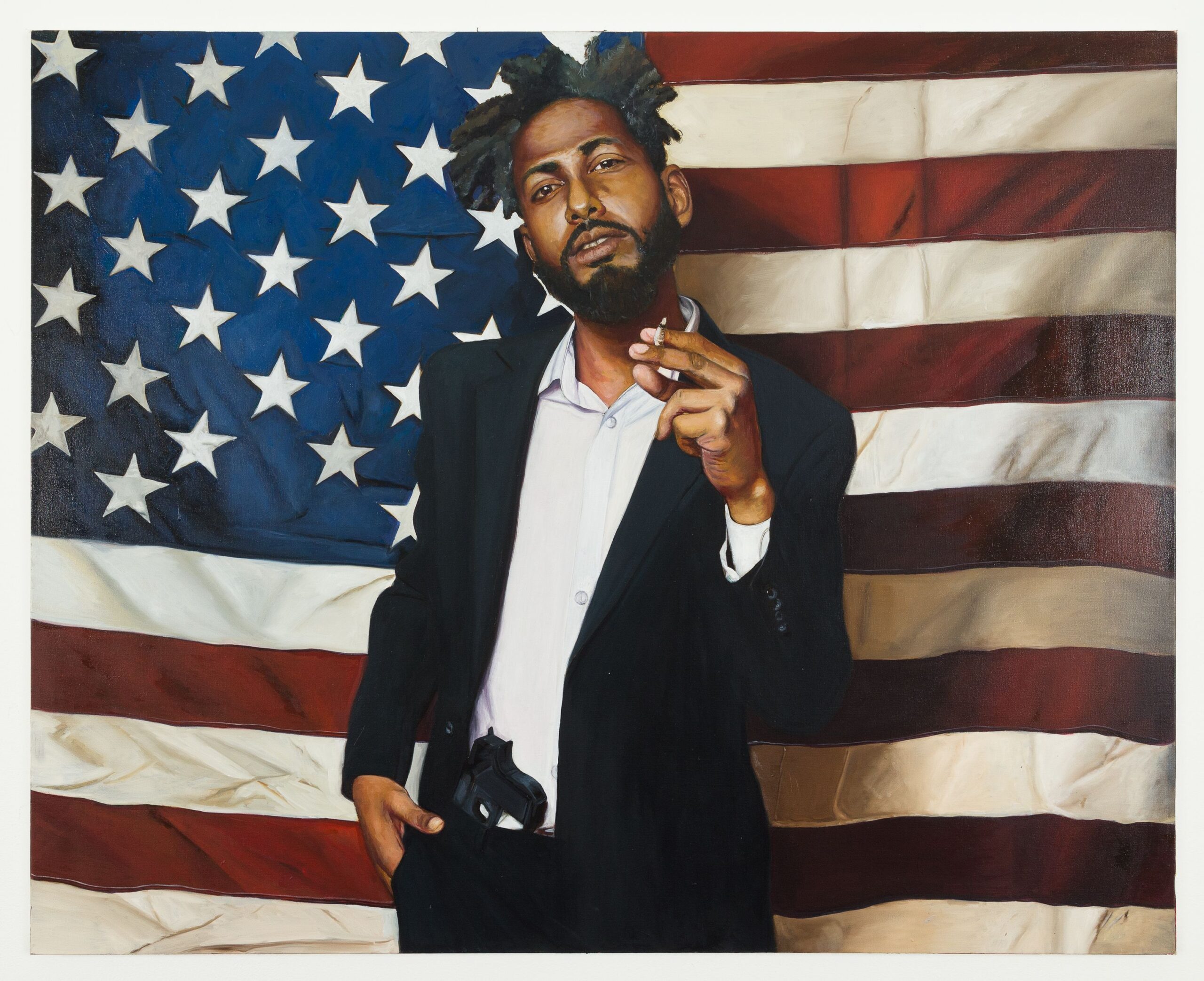

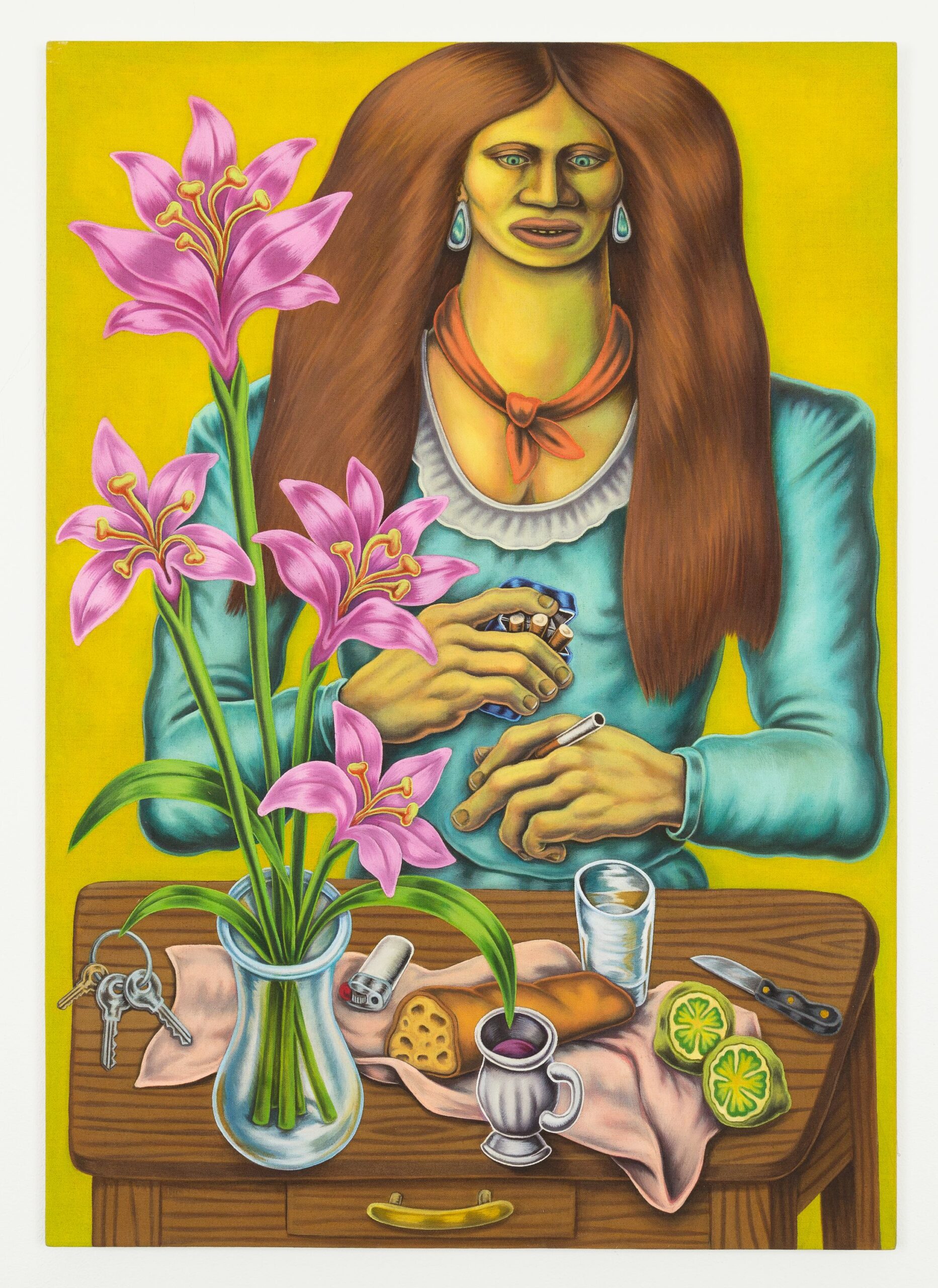

In Galerie Camille’s back gallery, Nelson strikes a reverential note with her complex, multi-faceted installation Altar, a ritual display that features devotional objects: feathers, candles and nests, along with drawings. The immediate mainstream association to a visitor might be with the commemorative ofrendas that appear yearly in Hispanic households for the Dia de los Muertos. This is a perfectly satisfactory association as far as it goes, but it’s likely that Nelson is also referencing devotional shrines of the African Yoruba religion, which forms the basis for a number of diasporic belief systems such as santeria and vodou.

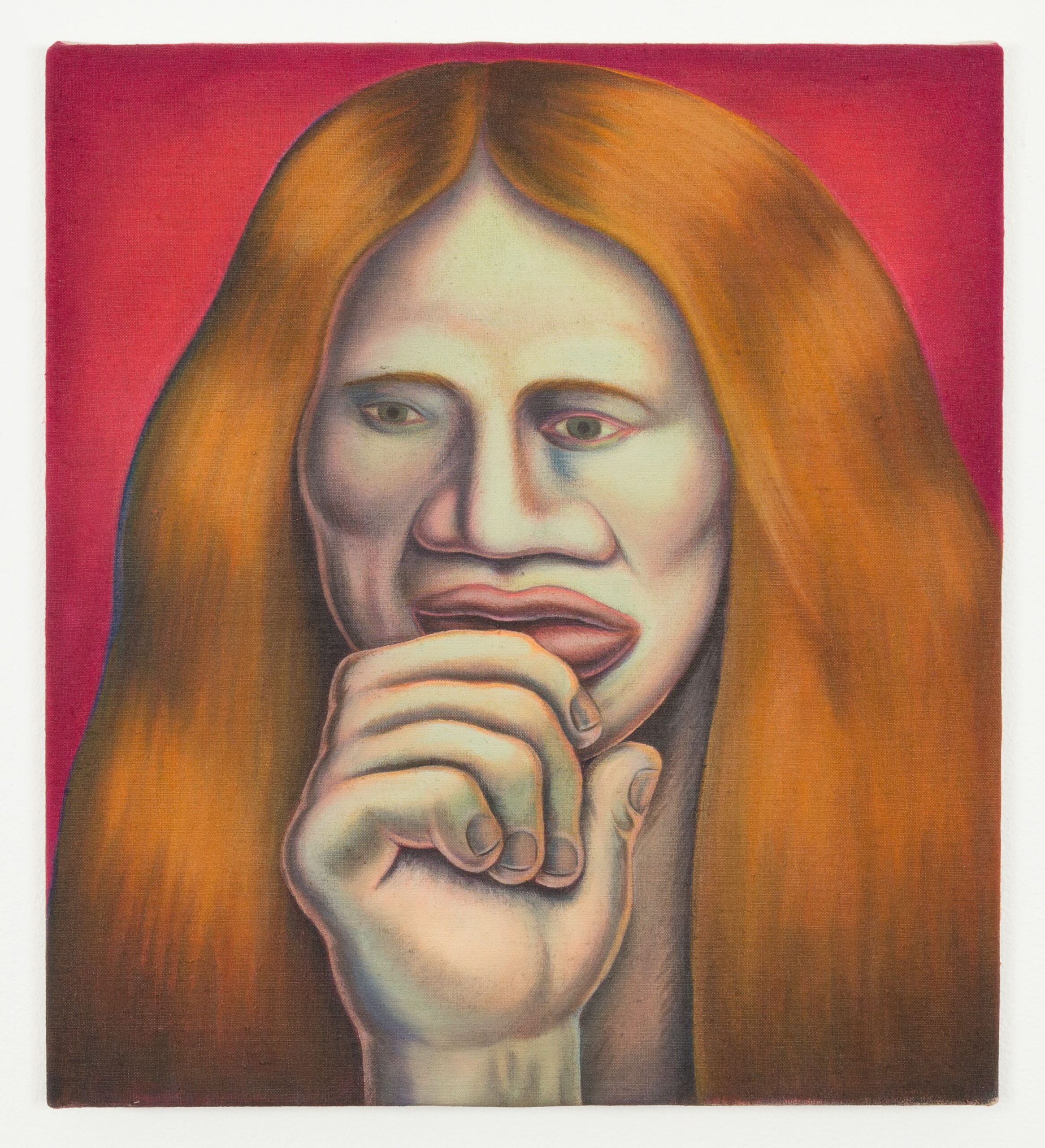

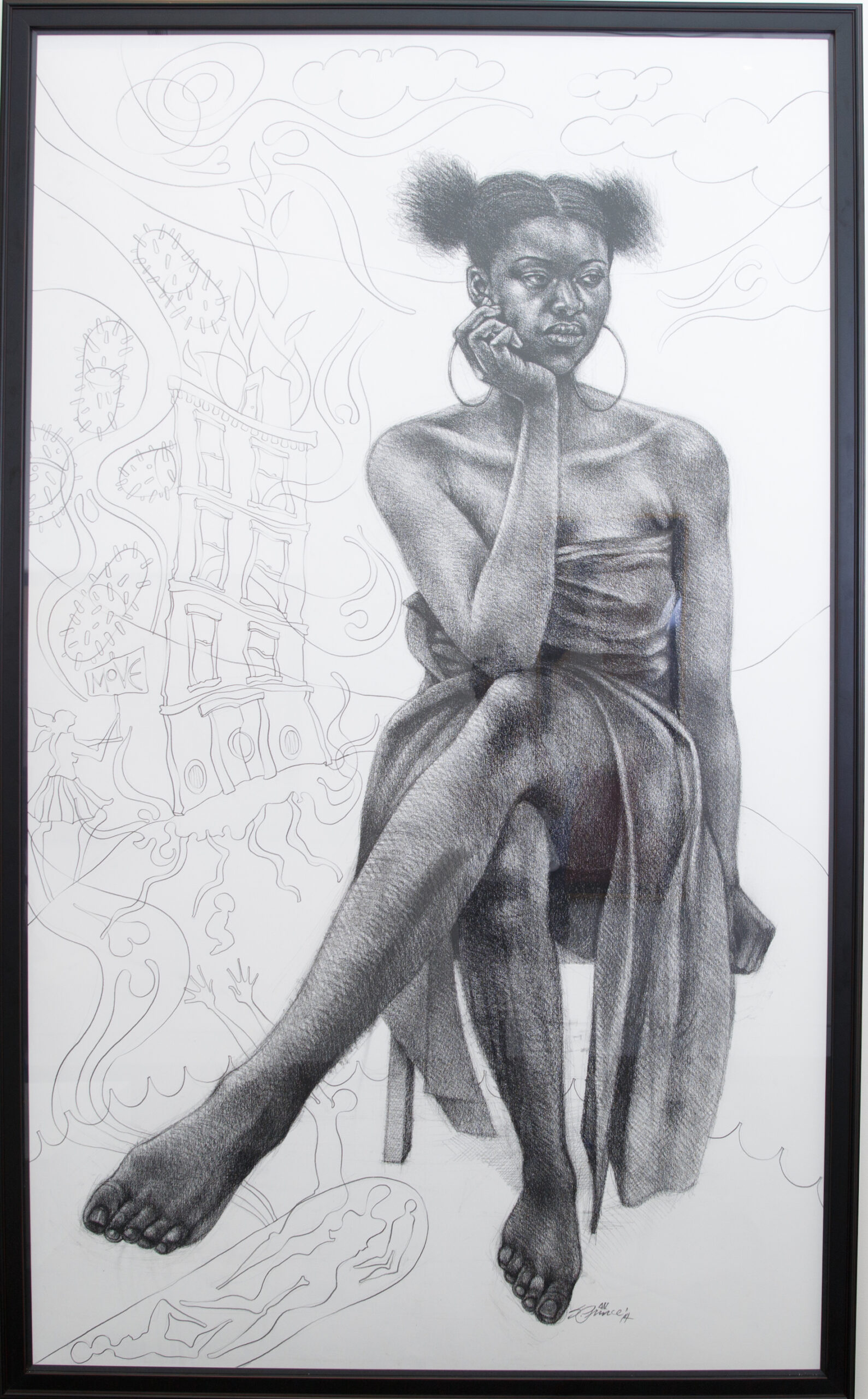

Nelson is an accomplished draftsman, and her skills are on display throughout the exhibit, but are especially striking in her wall of small drawings in the gallery’s Cube Room. Her handling of the water media in They Go in Threes is technically impressive and emotionally resonant. She employs the liquid properties of the paint to suggest shadows and fugitive movement. The drawings hint at both the presence and absence of bird souls, the accretion of images delivering a powerful charge of nostalgia and a suggestion of violence in the dripping inks.

Sabrina Nelson, Altar, installation, mixed media

Nelson specifically references Black singer Nina Simone’s lament Blackbird (released 1966) as an influence in developing the work for this show:

Why you want to fly Blackbird you ain’t ever gonna fly

No place big enough for holding all the tears you’re gonna cry

’cause your mama’s name was lonely and your daddy’s name was pain…

The continued relevance of Simone’s lyrics serves as an indictment of our slow progress toward racial equity. Paul McCartney’s Blackbird, from the same period, is also about the struggle for Black civil rights, but strikes a more hopeful note:

Blackbird singing in the dead of night

Take these sunken eyes and learn to see

All your life

You were only waiting for this moment to be free…

In Blackbird and Paloma Negra: The Mothers, Sabrina Nelson channels the mood of this moment in history in the U.S. and in Detroit. There is grief and pain, yes, but also hope.

An Artist Talk will be held on Sept 18, 3:00 p.m. Live on our Facebook and Sabrina’s Instagram live feed @sabrinanelson67. Galerie Camille hours are Wednesday through Saturday from noon to 5 p.m., by appointment during the pandemic. Please make an appointment by email [email protected]