Frank Stella, Takt-i-Sulayman Variation I (Protractor Series) 1969, acrylic and fluorescent acrylic on canvas

It has always seemed to me that the most magical thing about art objects in a gallery is that they exist at the same time and place, in the same now, no matter when they were created. An archaic vase, a classical Greek sculpture and a minimalist painting can rest side by side, in a kind of eternal conversation that illuminates how humans think and perceive, and what they value over time. This thought re-occurred to me with some force as I walked into the main gallery of the Cranbrook Art Museum last week, to see Shapeshifters, an eclectic exhibit that draws from the museum’s collection of over 6000 artworks. It covers a broad range of modern and contemporary artists and esthetic philosophies, all in lively conversation with each other and with us. Much of the work on display is by international artists with big reputations, but voices and visions of many younger, less established, artists have also found their way into Shapeshifters. Often these artists are from the Detroit area, many of them graduates of Cranbrook Art Academy’s M.F.A program; to my mind they provide the most interesting pieces in a wide-ranging survey of artists’ methods and mindsets.

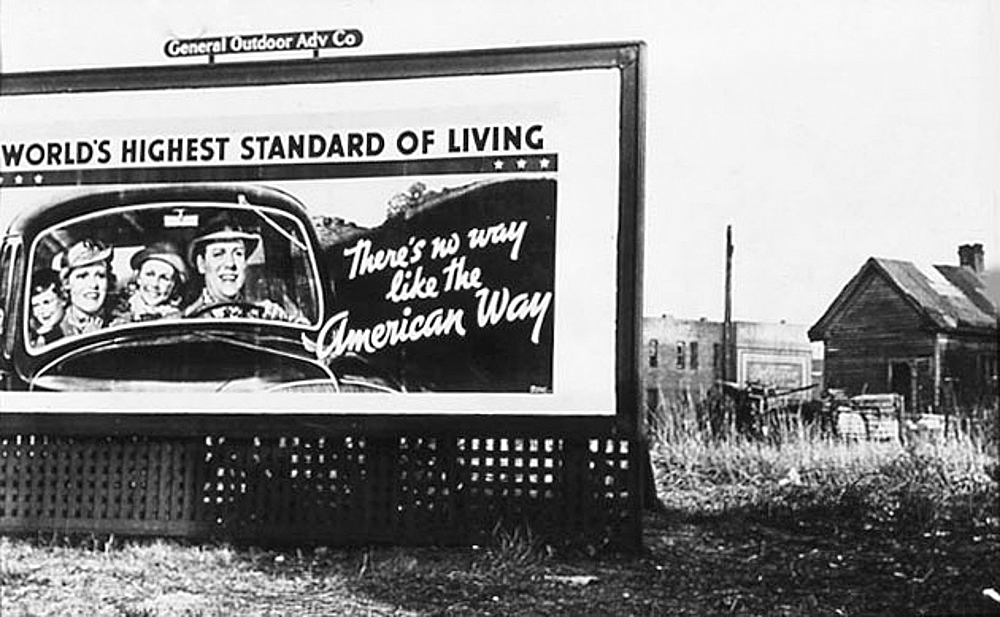

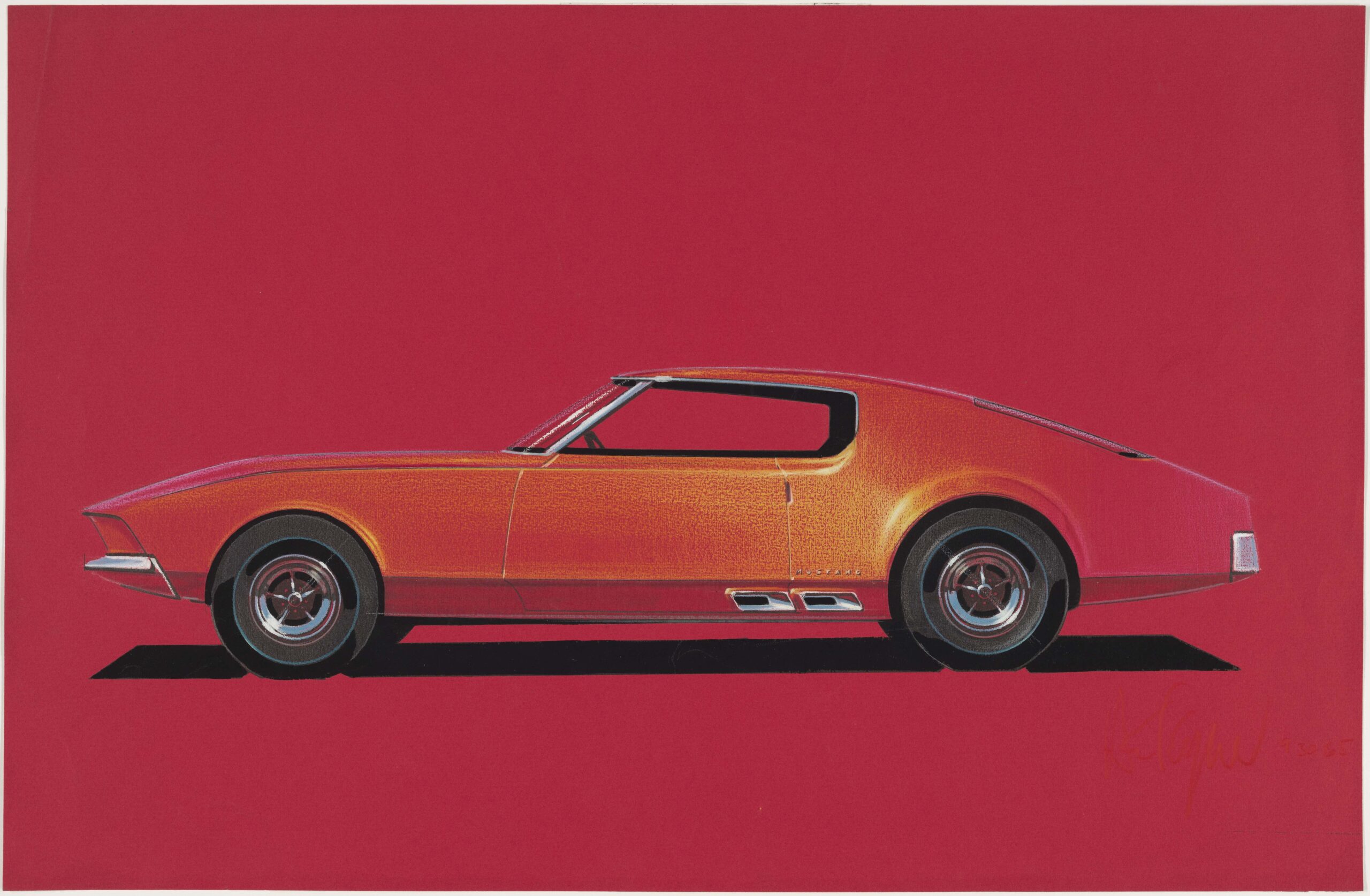

The entry gallery of the museum announces the ambitious nature of the exhibit with a forceful collection of minimalist and post-minimalist artists. Paintings and sculptures by art historical heavyweights like Donald Judd and Frank Stella ring the gallery. These self-referential abstract objects and images hark back to a brief moment in art history, 1960’s and 1970’s, when the methods and formal objectives of contemporary art seemed clear. These confident–and also mostly white, male–artists seemed to say they had found the endpoint of modernism, after which no further progress was possible–or necessary. Even Agnes Martin, whose (usually) much smaller pieces seem more interior and meditative, is represented in Shapeshifters by a large canvas, Untitled (1974) that shows her to be a member in good standing of the minimalist club.

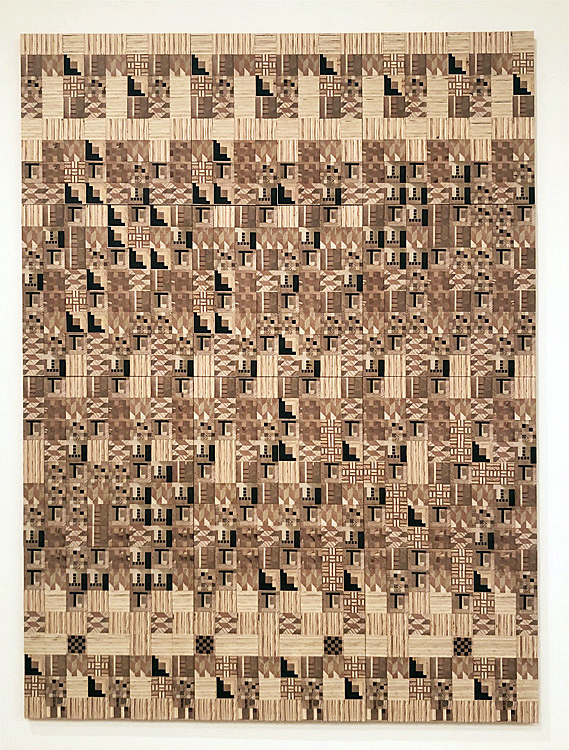

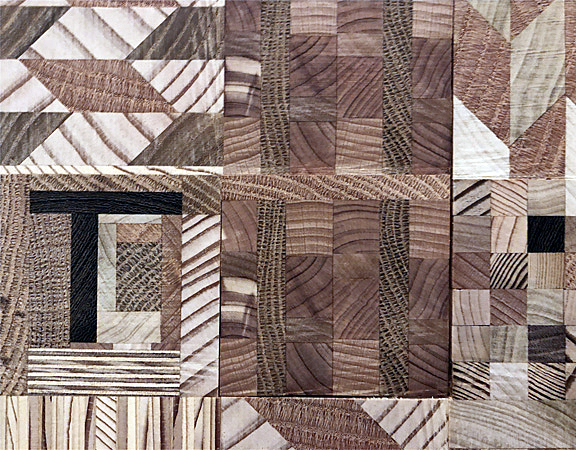

Ato Ribeiro, Home Away From Home 2, 2017, repurposed wood, glue

Ato Ribeiro, Detail

But even as these monumental, even grandiose, pieces stake their claim to dominance in this room and in art history, the show’s curator Laura Mott, slyly introduces an artist who says, quietly, “yes, but…”

Ato Ribeiro, a 2017 graduate of Cranbrook’s print program, has created a wood assemblage that superficially resembles many of the pieces in the main gallery, but suggests alternative cultural references that speak to more private, idiosyncratic aims. Home Away from Home 2 is a pieced quilt of a sort, made of discarded wood, re-cycled and re-assembled into an elaborate composition that references hieroglyphs, Kente cloth, traditional African symbols, and signals a turning away from minimalist generalities and toward more particularized personal references.

Ebitenyefa Baralaye, Dupp Dup, 2016, plaster, burlap, sisal rope wood

This insistence by young artists on private processes and meanings continues in the next gallery, with the awkward yet elegant and slightly comic Dupp Dup by Ebitenyefa Baralaye. A 2016 M.F.A. graduate of the ceramics program at Cranbrook, Baralaye has re-purposed the process of ceramic casting in a literally heartfelt way. The shape of the plaster cast is reminiscent of a human heart, signifying both a physical state of being and an emotional state of desiring. Its implied weightiness is animated and supported by a spindly wooden tripod. In the adjoining gallery, Sonya Clark’s scratchy ziggurat of a headpiece, assembled from hair curlers, is both humble and regal. Clark re-imagines these everyday materials using processes familiar to her from her background in fiber art; the result is both surprising and satisfying.

Sonya Clark, Curled, 1998, metal hair curlers, thread, wire

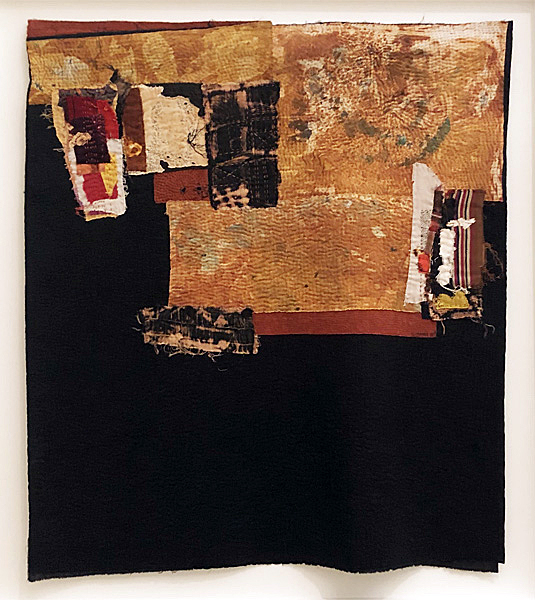

Two of Detroit’s art eminences occupy the middle gallery and are hung in proximity with two other artists who reinnforce and illuminate their importance as masters of their craft and figures of note in Detroit’s contemporary art scene. Allie McGhee’s folded and draped Window (2019) easily holds its own next to the much larger–and very lovely–Preface for Chris by Joan Mitchell, with which it is paired. McGhee is scheduled for an upcoming solo exhibition in the fall of 2021, and Windows provides a tantalizing foretaste of what we can expect and hope for. Carole Harris, whose work impresses me more each time I see it, is represented by In a Silent Way (2017). Harris is a textile virtuoso. Her work occupies the surprisingly capacious space between expressive quilting and painterly abstraction, and somehow manages to be more than the sum of the two mediums. The way in which she exercises complete control of flat or felted or lacy textures, of staccato stitched lines, of carefully dyed and rusted colors, adds a tactile element to her work against which the nearby untitled painting by Jose Joya struggles to compete.

Allie McGhee, Window, 2019, acrylic, enamel, vinyl

Carole Harris, In a Silent Way, 2017, quilt with rusted textiles

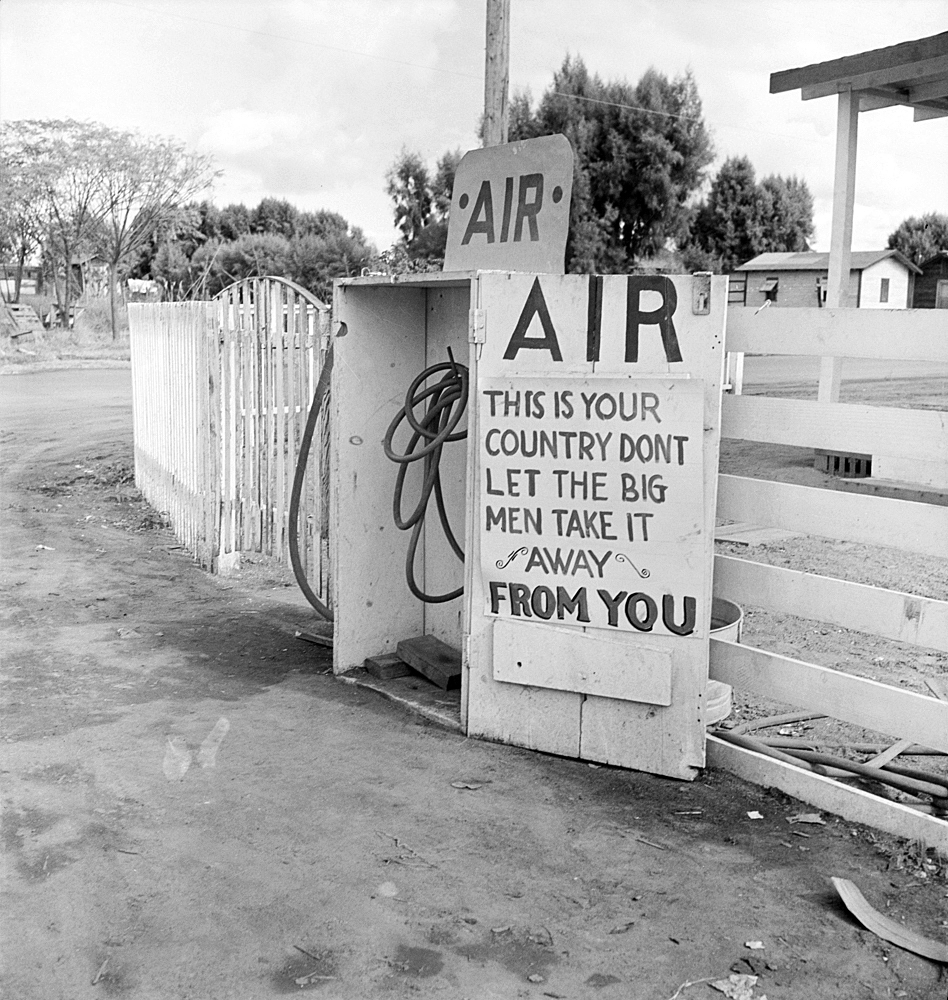

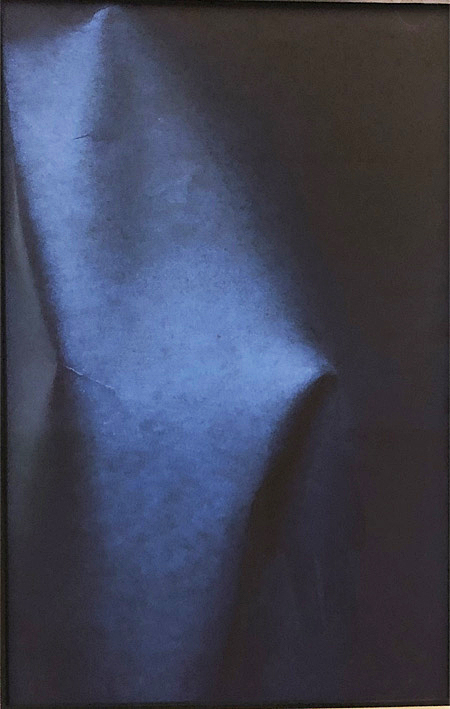

In the next gallery, photography –and related technologies–has its day as a means to revelation. The prosaic, descriptive reality of everyday photography gives way to the deeper truth of artists’ personal and subjective experience. A particularly beautiful example of this is Kottie Gaydos’s Unfixed, Fold #3, a dreamy, undulating field of deep blue in which a minimalist strategy yields a deeply romantic and poetic image. Matthew Angelo Harrison’s low-resolution replicas of African artifacts by way of his homemade 3-d printers are familiar to most of the Detroit art public by now, but they remain impressive, resonant in their expression of the African American diaspora’s sense of cultural loss from the trauma of enslavement.

Kottie Gaydos, Unfixed, Fold #3, 2016, archival pigment print, artist frame with unfixed cyanotype

The wan ironies of Andy Warhol’s Polaroids and Rosenquist’s lithographs are interesting as historical artifacts, but pale beside Kara Thompson’s polemical silhouettes and the robust immediacy of Maya Stovall’s dancers, doing their thing in the parking lot of a Detroit convenience store. Her video, Liquor Store Theatre, Vol. 4, No. 7, records the bemused reaction of bystanders along with the precise and angular movements of the black-clad performers.

Maya Stoval, Liquor Store Theatre, Vo. 4, #7, 2017, video still

The back gallery of Shapeshifters is devoted, appropriately for an exhibit about transformation and adaptation, to a short feature film entitled Upright: Detroit. Set in the ruins of the historic Michigan Theater, the film records a kind of initiation. Performers arrive, one by one, dressed in ordinary street clothes. Here, they are ritually transformed, with assistance from members of the Ruth Ellis Center for LGBTQ+ youth, into other-worldly beings by way of Nick Cave’s iconic Soundsuits. In the subsequent procession, initiates are accompanied by a choir of singers from Detroit’s Mosaic Youth Theater. With this performance, Shapeshifters brings us full circle, from the exuberant hubris of the minimalists to the joyous communality of the performers in Upright: Detroit, a thought-provoking journey from the general to the personal in search of our universal humanity.

Artist in Shapeshifters: Richard Anuszkiewicz, Jo Baer, Ebitenyefa Baralaye, Romare Bearden, McArthur Binion, Susan Goethel Campbell, Anthony Caro, Nick Cave, Nicole Cherubini, Sonya Clark, Liz Cohen, Conrad Egyir, Beverly Fishman, Kottie Gaydos, Sam Gilliam, Kara Güt, Carole Harris, Matthew Angelo Harrison, José Joya, Donald Judd, Agnes Martin, Allie McGhee, Marilyn Minter, Brittany Nelson, Kenneth Noland, Marianna Olague, Robert Rauschenberg, Ato Ribeiro, James Rosenquist, Beau Sinchai, Julian Stanczak, Frank Stella, Maya Stovall, Toshiko Takaezu, Carl Toth, Kara Walker, Andy Warhol, and Richard Yarde, among others.

The museum is open with some restrictions. For more information, go to: https://cranbrookartmuseum.org/plan-your-visit/