A Light at the End of the Tunnel- Caledonia Curry (Swoon) at Library Street Collective

“…You can start to create little cracks in the façade of possibility and inevitability that overlays all of our lives.”-Caledonia Curry at her TED Talk, 2010

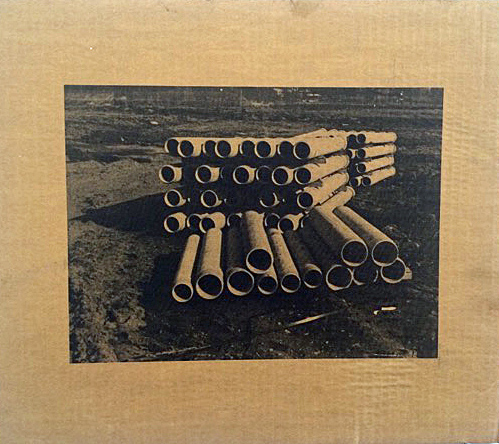

Swoon, Installation Image, All Images Courtesy of Clara DeGalan and Sal Rodriguez

Caledonia Curry (tag name Swoon) seems intimately aware of the ephemeral, fragile nature of both the human body and human endeavor. This sensibility weaves through all of her bodies of work, which make up for the degradability of their materials with iron-clad social consciousness and fierce political engagement. Curry first gained attention on the global art scene for her large scaled, lyrical street art prints, which, like her work at Library St Collective, engage with the figure overlaid with gorgeous lacework of iconic decorative flourishes and symbols. Curry would scout out locations for her prints, then install them, on walls, lamp posts, and other architectural surfaces, using wheat paste. These delicate cut-paper and print collages are not meant to last forever- they fade away, gently and gradually, like distant memories. To Curry, physical immortality of work is beside the point- this seems unusual, given the highly formal, decorative nature of her constructions. What such highly developed technical skill and labor intensive process is meant to foster is less reverence for the made object itself than a holding of space for a new perspective, a chance to recontextualize one’s relationship with place, with symbolism, with one’s own identity.

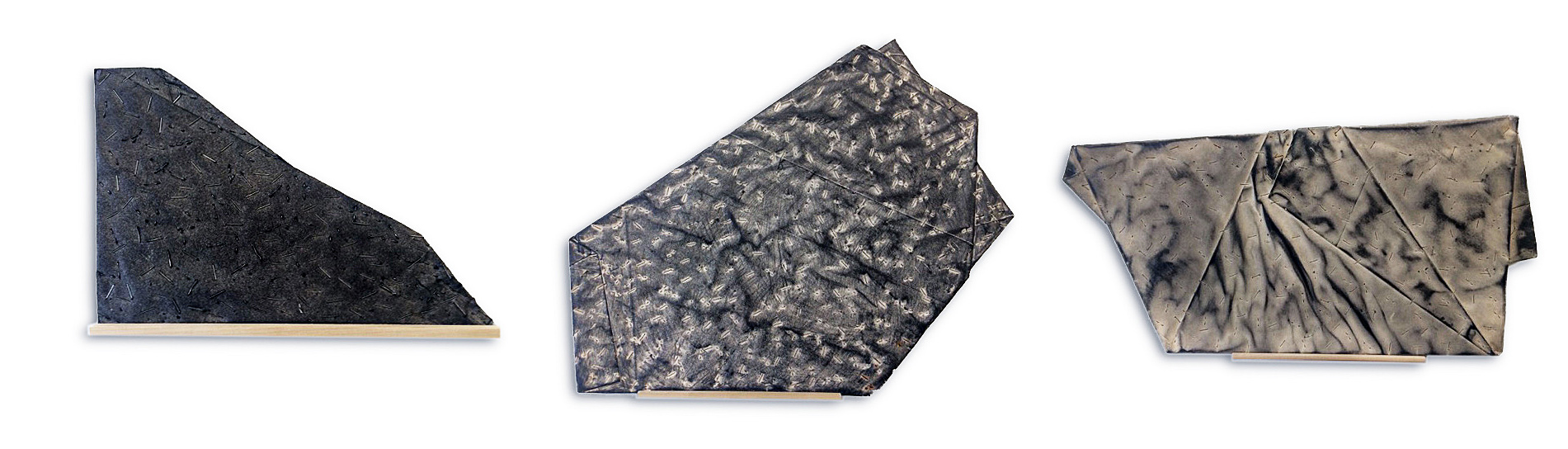

The same curious mixture of preciousness and ephemerality finds its way from Swoon’s street art practice into Curry’s site specific installation at Library St Collective. As lovingly wrought and beautifully realized as Curry’s life-sized figurative prints and elaborate cut paper confections are, they are installed with no greater measure of preciousness or economic value than her wheat pasted public works. Curry’s figurative cut out prints hang suspended from strands of fishing line, freed from the relative safety, and canonical indexing, of traditional wall installation. They move in the breeze- they’re equally visible from front and back. Curry’s incredible paper cut-outs, executed in black and white and resembling every beautiful, lace-like form a viewer can call up, from snowflakes to double helixes to Celtic knot work, drape freely from the gallery’s ceiling and dangle, like the figure cutouts, from strands of fishing line, inviting touch, uncannily mimicking the slight movements of sentient life.

Swoon cut paper intallation-detail

The heaviness of Curry’s concept for her site specific install at Library St is what grounds these floating works. Taking the narrow, tunnel-like structure of the front part of the gallery as inspiration, Curry is attempting, with The Light After, to recreate for the viewer her own narrative of a phenomenon known as “the empathetic death experience.” Curry encountered this phenomenon in a dream of a space filled with falling snow and “blossoms of light,” during which she felt that her mother had died. Upon awakening, she discovered that her mother had, indeed, passed away.

The snow-blossom motif of Curry’s installation occupies Library St.’s space as a tunnel of atmospheric light similar to those described by people who have had near-death experiences. Dispersed around this bright, ungrounding fairyland are Curry’s life-sized figurative prints which, despite their ephemeral construction, nail the viewer with quietly appraising or imploring gazes, each taking the form of a step on the initiation path toward death. Curry’s figures are iconic- an old, bearded hermit leaning on a walking stick, his lower body morphing into ramshackle architecture which crumbles, at his feet, into a profusion of skulls. A heartbreaking double image of a woman filled with youth and vitality, holding a baby, while her forward-projected shadow looms behind her, emaciated, rigged up with oxygen tubes, her eyes engaging the viewer’s in abject, human terror of proceeding down the very tunnel that surrounds her.

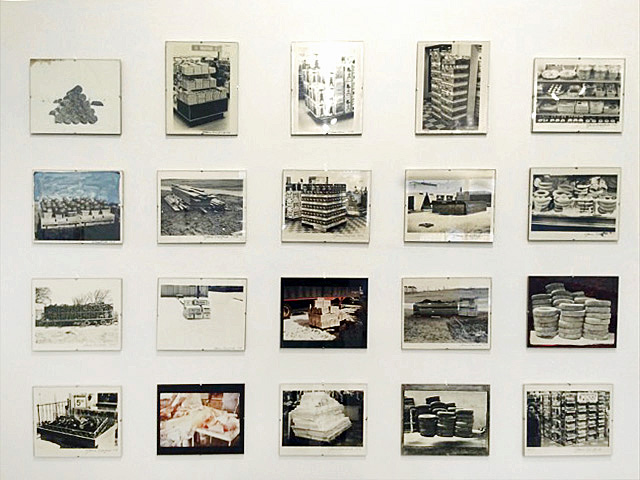

Swoon, Memento Mori, 2016, block print on hand cut mylar,edition3 of 12, 84-x-67″

Curry takes the viewer through this legendary tunnel, which leads into a stark hallway painted in black and white geometric and organic forms- a nice visual metaphor for the space between the end of the tunnel and what comes after- into the gallery’s larger, airier back room or, as Curry titles it, “The Meadow.” The figurative prints in The Meadow aren’t allegories of death, but of rebirth- the color scheme of The Meadow is warmer, more organic, the 3D elements more tactile and sensual- piles of green velvet take the place of the ethereal cut-paper hangings within the tunnel. Mother-child pairings and figures surrounded by simple, ancient symbols of life and birth- paisleys, triple knots, spirals- gaze invitingly out or, more often, appear turned inward, eyes closed, in a private ecstasy of union with the life-power of the universe.

Swoon, Milton II, Diogenesis, 2016 block print on hand cut mylar edition, 3 of 6 89×66″

There’s an uncanniness, a formal directness, and a powerful combination of personal and political narrative to Curry’s work that makes it difficult to contextualize in contemporary studio practice. The bald allegory and mirror-image rendering of her figure-prints awakens the viewer to the power of such imagery as expressed in every layer of our society, from religious painting to Chuck E. Cheese animatronics- all of them evoke the same frisson. Curry’s work reveals why this is so. Confronted with our own image reworked into symbolism, we begin to examine the foundations of universal truths- birth, death, spirit, the afterlife, the sentience of so-called inanimate objects- with the understanding that these truths emanate from our own bodies. Our bodies are ephemeral. What we can do with them, change with them, what we can leave to succeeding generations, is eternal. It is this truth that forms the kernel of Curry’s work in every medium and context that she engages.

“Swoon- The Light After” is on display at Library Street Collective through November 26, 2016.