Todd Weinstein’s Stories of Influence: In Search of One’s Own Voice is at the Janice Charach Gallery in West Bloomfield, Michigan through Dec. 7.

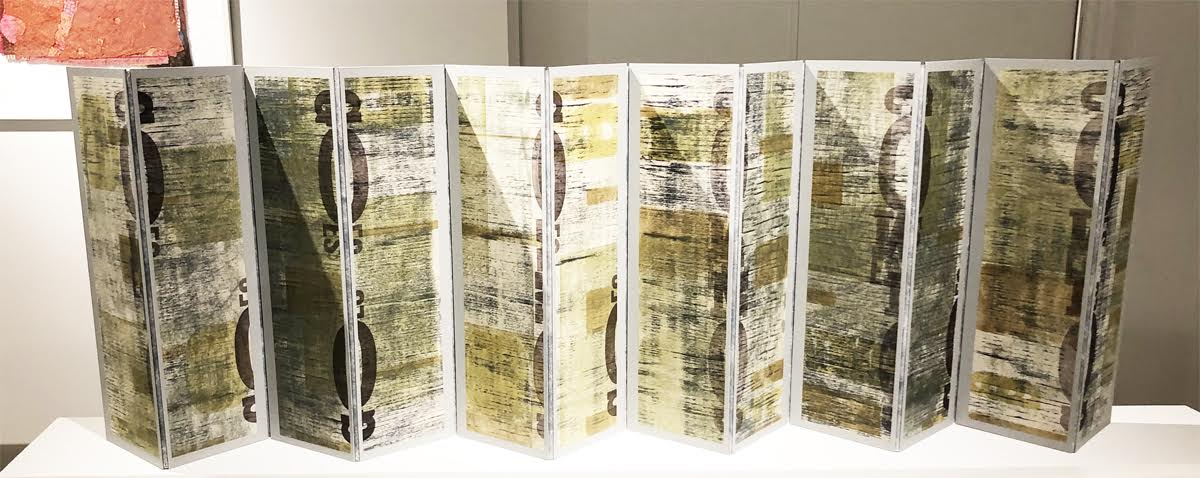

Install image, Stories of Influence: In Search of One’s Own Voice is at the Janice Charach Gallery in West Bloomfield, Michigan. 2022

Photographer Todd Weinstein’s Stories of Influence: In Search of One’s Own Voice is a high-concept show that employs a delightful gimmick – Weinstein pairs 68 of his photos with a corresponding image from one of his numerous mentors, teachers and friends, and then mats and frames the two together. It’s a career retrospective with punch, and will be up at the Janice Charach Gallery in West Bloomfield’s Jewish Community Center of Metropolitan Detroit through Dec. 7, 2022.

A commercial and artistic shutterbug who grew up in Oak Park, Weinstein had a gift as a youngster for talking his way into jobs with great photographers, some of whose influence he honors with this exhibition. He got an early start after dropping out of the old School of the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts (now the College for Creative Studies), and approaching legendary auto photographer Dick James to ask if he needed an assistant. “How about third-assistant?” James responded. No fool he, Weinstein grabbed the chance.

Like so many young artists in the 1970s, he ultimately left Detroit in the 1970s to make his way in New York’s hurly-burly, and, as it happens, thoroughly succeeded. Weinstein’s got a thriving photography and multi-visual practice, and lives in one of Brooklyn’s handsomest old rowhouse neighborhoods, Boerum Hill.

Among other virtues, Weinstein appears to have an admirable gift for gratitude. The idea of pairing one of his photos with that of an esteemed teacher, mentor or friend as a way of paying tribute struck him when he was in Paris several years ago. Weinstein brought it up with Charach director Natalie Balazovich, and she was immediately enthusiastic, finding it refreshing and new. “Todd’s essentially saying ‘This is why I’m where I’m at,” she said, “’because of these people.’” She added, “I like that the show dives into almost a taboo subject – sharing the things that pushed him to become who he is, and showcasing them.”

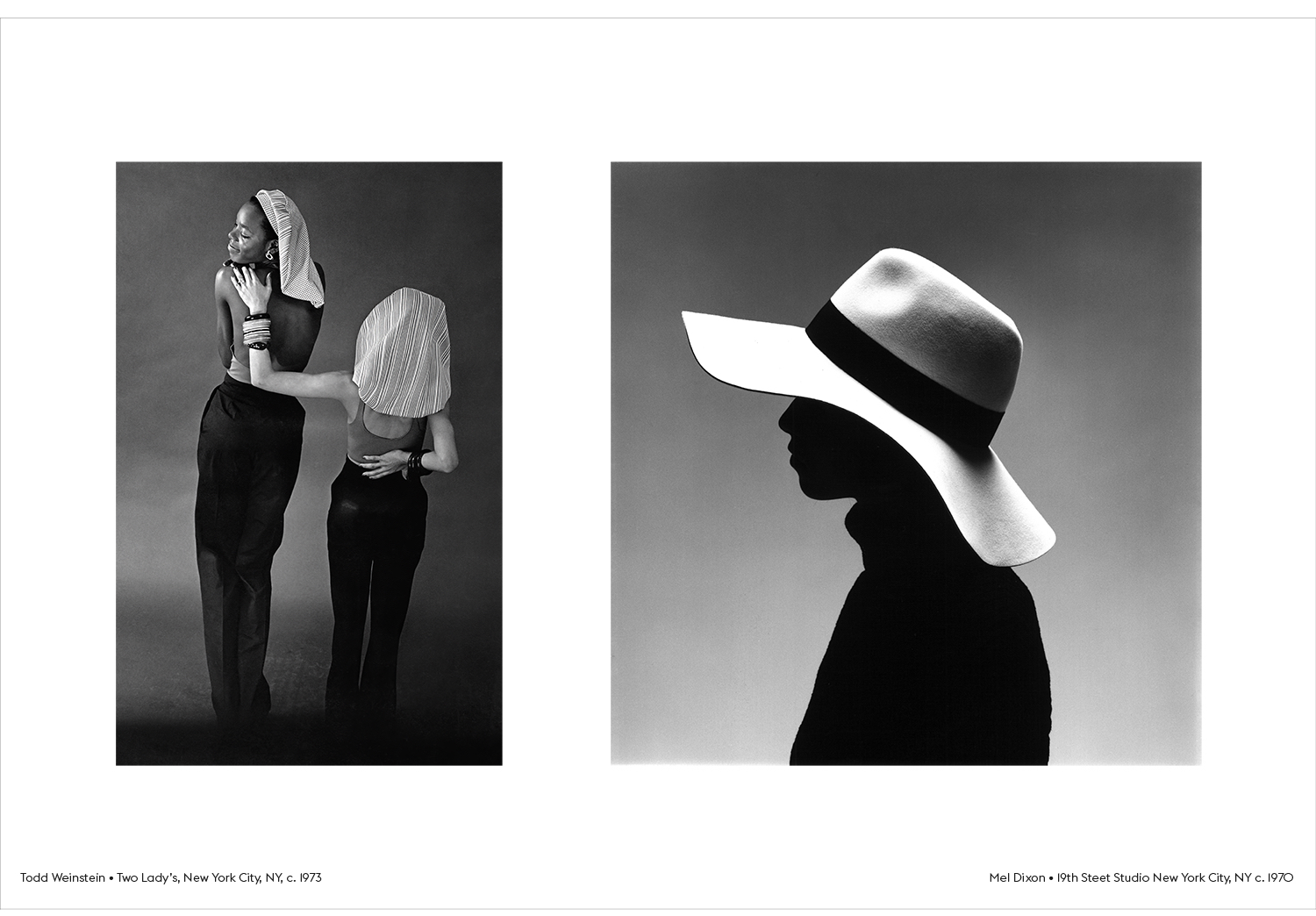

Todd Weinstein, Two Lady’s, New York City, NY, c. 1973; Mel Dixon, 19th Street Studio, New York City, NY, c. 1970.

A professional who helped Weinstein in his early New York days, when he was sleeping on a friend’s floor for eight months, was commercial photographer Mel Dixon. One of the first Black fashion photographers to go out on his own some 50 years ago, Dixon had a glittering background – he’d worked with photo greats Avedon and Hero. He offered Weinstein his first job in the big city, working in the studio on commercial and advertising projects.

“Mel gave me the chance,” Weinstein said. “We shot luggage, brides. All that kind of stuff.” He wasn’t really that interested in studio work, but it gave him the opportunity to earn a living while exploring other paths for his future.

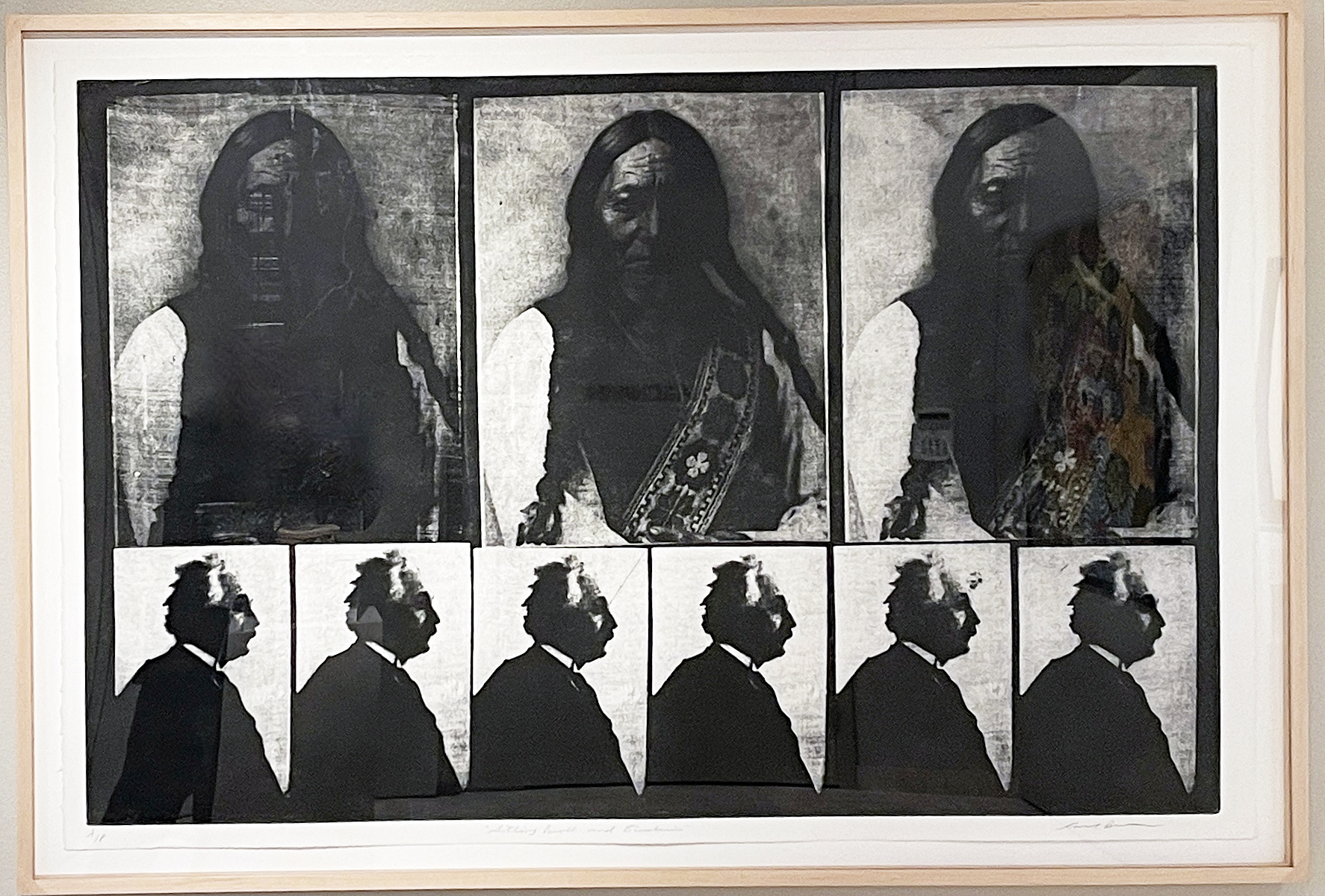

The image Dixon contributed to the show is a black-and-white study of a girl. Her shoulders and face are completely dark, while her broad, white hat catches all the light in the frame. It’s elegant, high-class, high-fashion photography.

In his artist’s statement, Weinstein notes that in pairing images he relied on the structures of jazz – employing a sort of visual syncopation, as it were. You clearly see that in his rejoinder, the 1973 Two Lady’s, New York City, NY. It, too, is a fashion study — this time of two models facing away from us, one lithe and Black, the other short and white. Both are wearing headdresses that fall like curtains down to their shoulders. The white girl has a hand on the other’s back, which prompts her to twist her head around in apparent rapture.

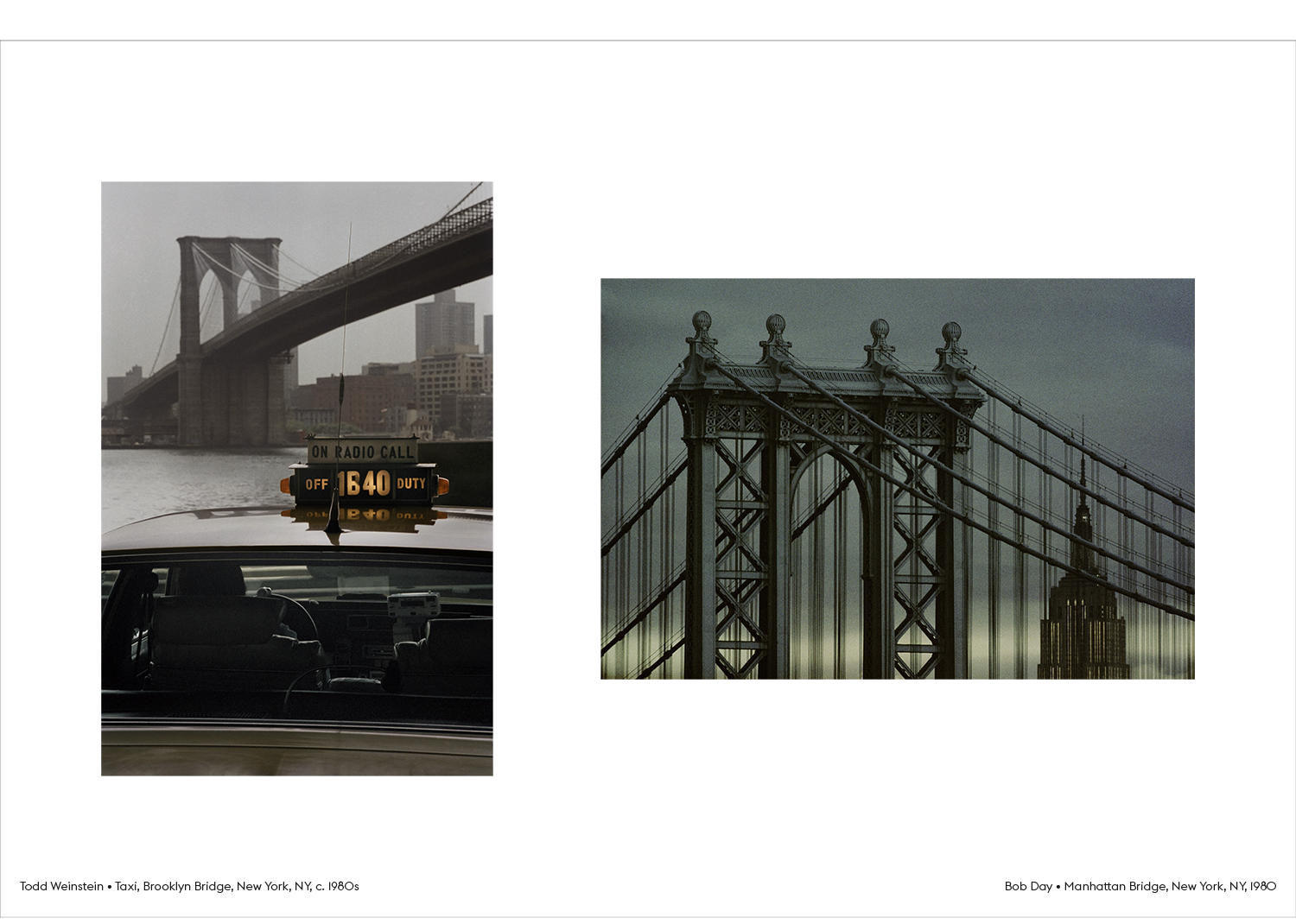

Todd Weinstein, Brooklyn Bridge, New York, NY, c. 1980s; Bob Day, Manhattan Bridge, New York, NY, 1980.

Another significant mentor was painter and photographer Bob Day. The two went into business together on Manhattan’s East 17th Street half a century ago, “back when you could get a 6,000-square-foot studio for like $300 a month,” Weinstein said. Day’s 1980 image, Manhattan Bridge, NY, NY, is a powerfully compressed telephoto shot. Day frames the very top of the Manhattan Bridge, a lush blue-green, sharply etched essay in cross-bracing around a central gothic arch. Looming in the near distance – unrealistically large, thanks to the powerful lens — is a gray and gold Empire State Building seen through the bridge’s vertical suspension wires. It lends immensely satisfying balance to the drama of the bridge crown in both shape and color.

By contrast, Weinstein’s Brooklyn Bridge, NY, NY is grittier. A close shot of a taxicab takes up most of the frame, the vehicle’s “Off Duty” crown lit and glowing. The aesthetic is ordinary and everyday — even the Brooklyn Bridge rising in the distance looks a little dull. All the print’s visual power, which is considerable, comes from the illuminated “Off Duty” sign that, alone out of the entire shot, glows with a warm light, and whose shape echoes the tops of the two bridges.

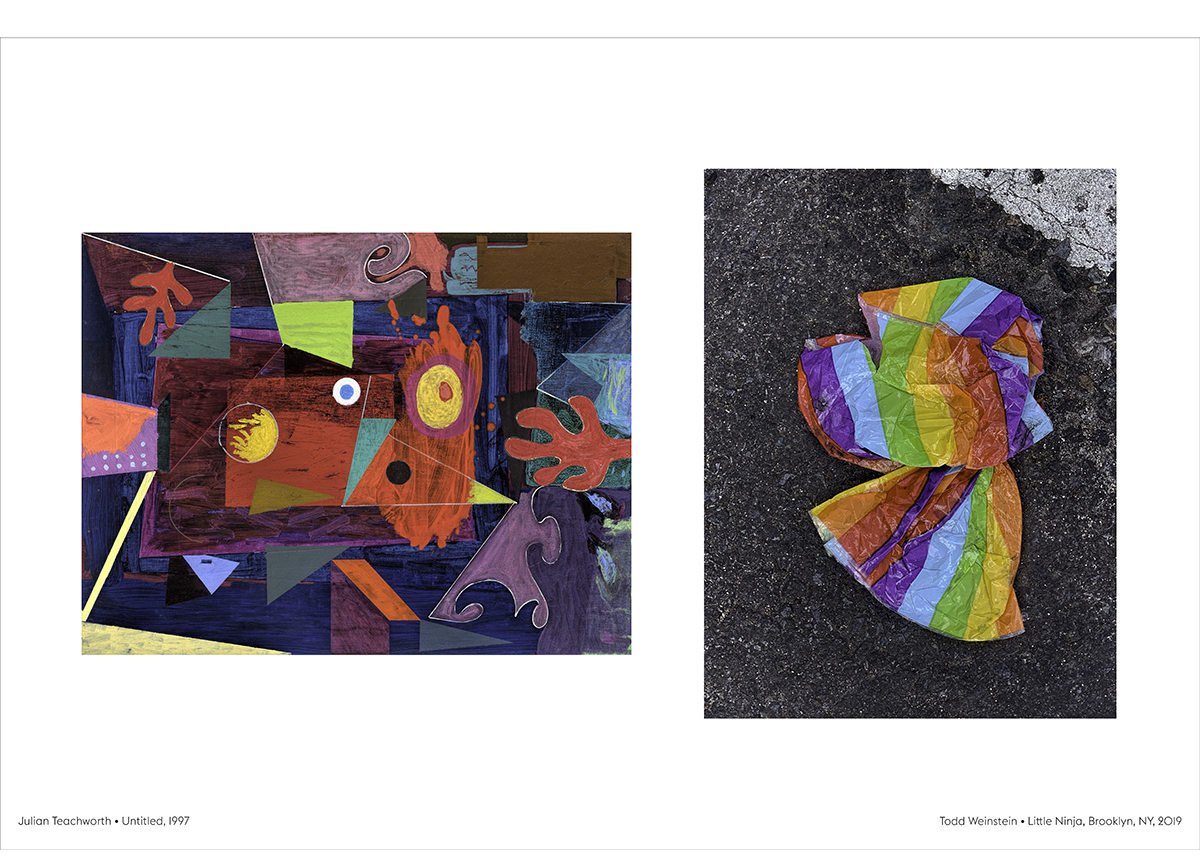

Julian Teachworth, Untitled, 1997; Todd Weinstein, Little Ninja, Brooklyn, NY, 1973.

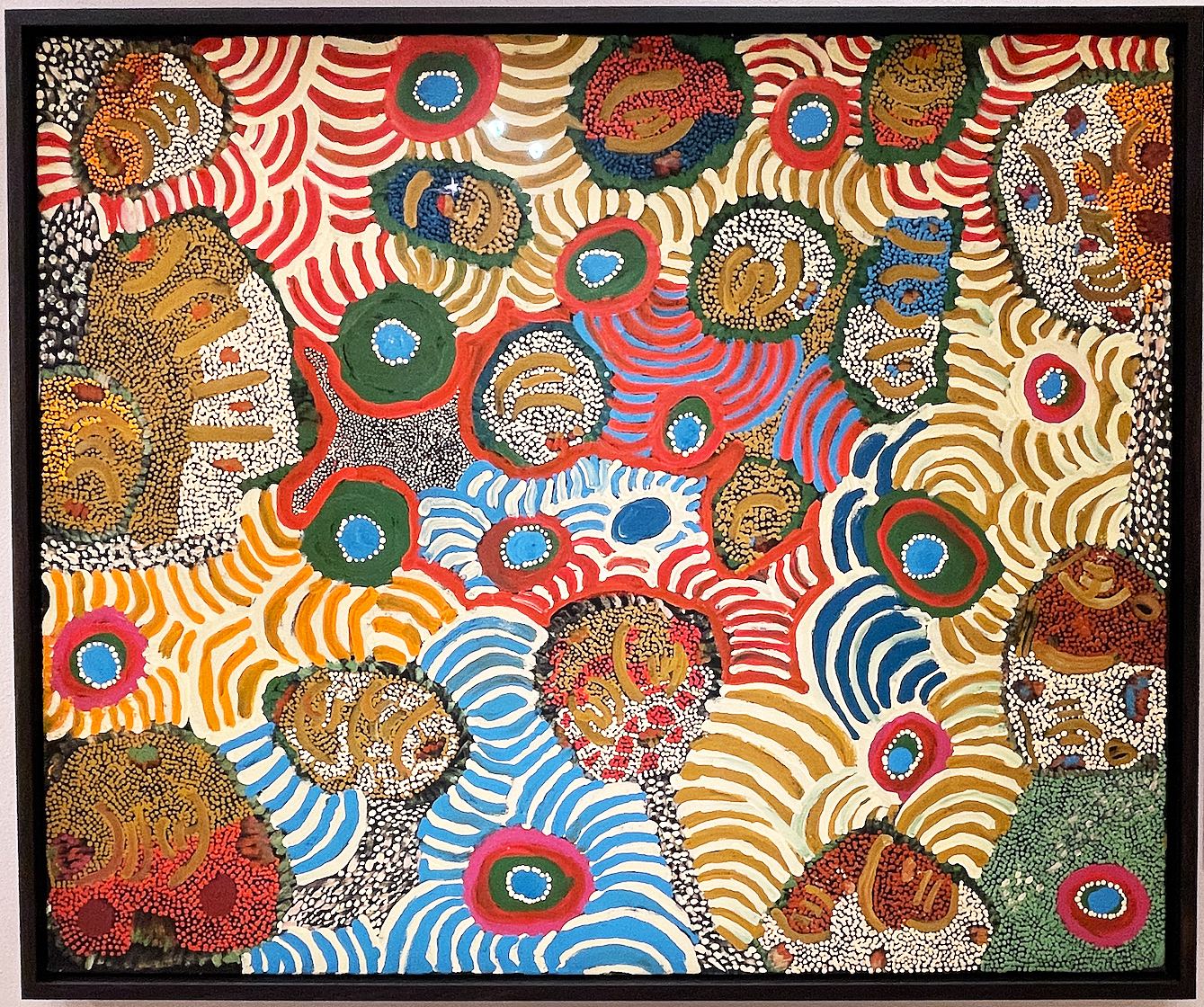

Not all of the images contributed by mentors are photos. In one, Weinstein pairs his picture of what looks like a collapsed, rainbow-striped mylar balloon on the street with painter Julian Teachworth’s amusing and gorgeous abstract of many colors, an untitled work from 1997. Here Weinstein riffs on the similarity in colors and the loopy geometry present in both. “I photographed all of Julian’s paintings,” Weinstein said. “He’s an incredible painter, mentor and spirit.”

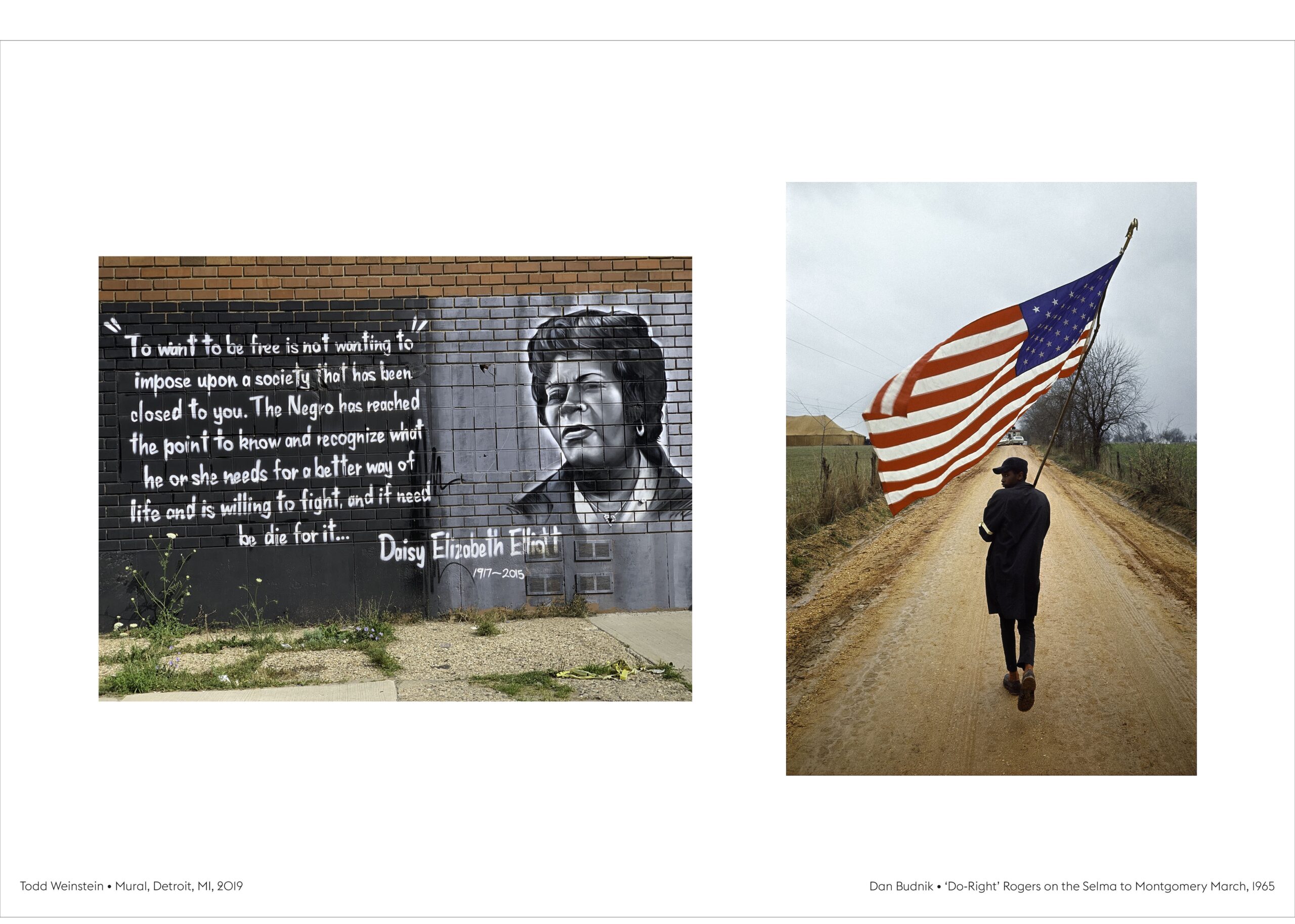

There’s something undeniably spiritual about the twinned images by Weinstein and the great photographer of the Civil Rights movement, Dan Budnik. The latter’s photo, ‘Do-Right Rogers’ on the Selma to Montgomery March, March, 1965 is a classic of the genre, and one that Weinstein says he recalls from childhood. A skinny, African-American youngster marches down an endless dirt road, carrying a pole with a large American flag that’s unfurled in all its red, white and blue glory. The association of deep patriotism with individuals who still had to fight a for their rights is palpably moving.

Todd Weinstein, Mural, Detroit, 2019; Dan Budnik, ‘Do-Right Rogers’ on the Selma to Montgomery March, March 1965.

For his part, Weinstein gives us a black-and-white mural in Detroit on a brick wall honoring the late Daisy Elizabeth Elliott, a champion of Black rights who died in 2015. The quote next to her portrait, in which she cites her willingness to die in the fight for civil rights, is powerful and unexpected – a bit like this show.

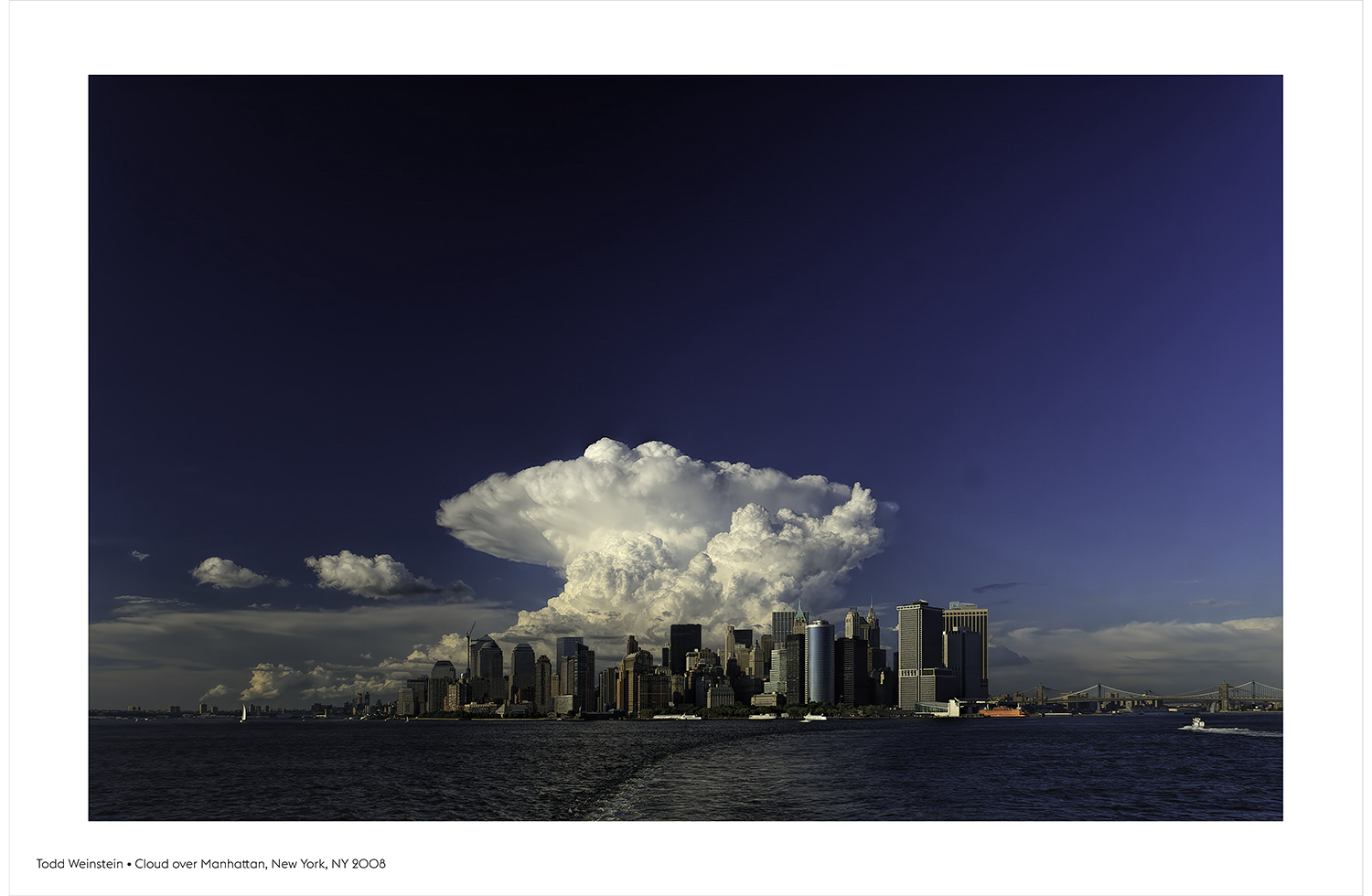

Todd Weinstein, Cloud over Manhattan, New York, NY, 2008.

Stories of Influence: In Search of One’s Own Voice is at the Janice Charach Gallery in West Bloomfield through Dec. 7.